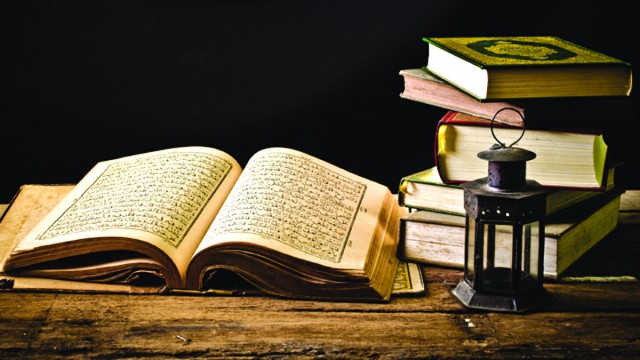

Reading the Qur’an can be a complicated, religiously as well as politically charged and value-ridden matter. Just like any scripture, the Qur’an can’t be treated just like another book. Scriptures contain truth, human and historical, or a grain of truth, expressed in transcendental and metaphorical language.

To get to the meaning and implication of the text of a scripture, the idiom of not only the language, but the whole projects of meaning-making, value extraction, normative and prescriptive codes as well as the socio-cultural complex associated and built around the text of the scripture has to be understood and realized both in reason as well as in feeling.

This matter makes reading scripture – the Qur’an more so because of the charged environment and the turn of modernity and the relation of Islam with modernity – an empathetic matter. And due to that, the activity of reading, comprehending and appealing to its authority (either to proselytize or detract), becomes all the more layered. In light of my own engagement with reading the Qur’an, making sense of the faith and to draw out meaning for myself and to comprehend the religious experience, I have undergone significant phases and shifts. While those changes and shifts can be extraneous to this article, but it has to be mentioned that my reading and engagement with the Qur’an was not always scholarly. For that matter, given my current understanding of the project of locating the text of the Qur’an in the historical and human complex of Islam as an object of experience, my understanding of scripture or its reading can’t be separated from my larger values and perspectives on life.

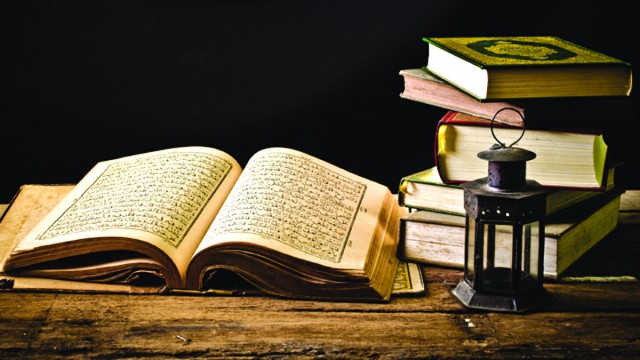

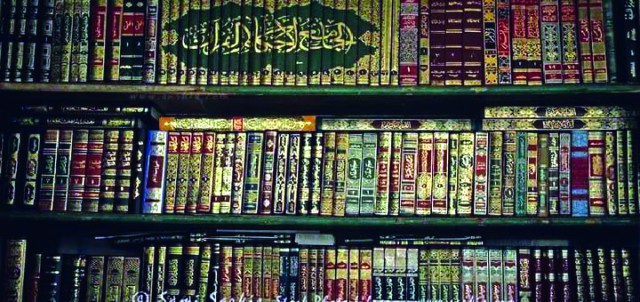

I started reading the Qur’an through Tafsir at an early stage of life. My first engagement was with Tafsir Maarif-ul-Quran which was composed of Qur’an and Tafsir lectures of the eminent Pakistani Deobandi scholar Mufti Mohammad Shafi. That exegesis is in light of the religious strain which has become the mainstream religious discourse. Access of the social engagement to the exegesis and Qur’an is unfortunately limited to such mainstream discourse of exegesis of Qur’an, which presents often the literalist version of Islam. Thus, engaging with Qur’an also is seen as an extension of that literalist strain of Islam. This is not to call for some kind of ‘critical’ engagement, for the term critical has such loaded connotations that it cannot convey anything meaningful.

I also don’t want to deny the importance of the Tafasir which often are the entry-way into larger engagement with the Qur’an and Islam for those faithful who want to go beyond rituals of worship and want to include a hermeneutical side to their understanding and practice of faith. This kind of Tafasir (taking Maarif-ul-Quran as a model which is a detailed one at 8 volumes) also provides a window to the creedal and theological basis of the religious authorities who now are synonymous with orthodoxy. I have found my engagement with this Tafsir not only my hermeneutical comprehension of the terms, values and dogmas of the current orthodoxy but also an exposure to the structure, message and functional aims of the Qur’an. Yet, I feel that such works leave the hermeneutical engagement with Qur’an (and historical Islam) at best truncated, and at worst, literalist-reductive. (There are other works, some a volume or two and others having more volumes than Maarif-ul-Quran who are referred to in our society but often the variation is in matter of length rather than the nature and form of theological or historical hermeneutical engagement.)

In Pakistan, there are other exegesis involved in the mainstream engagement which can be called modernist in nature, but which at best can be modernist-literalist (that is literalism presented in the language, vocabulary and idiom of modernism), for instance Tafhim-ul-Quran by Maulana Maududi (needs no introduction), or which can be ‘reformist’ in strain of the Tafsir by Amin Ahsan Islahi. (The term reformism/reformist needs a separate treatment in that how it came to be associated with ‘application of reason’ in hermeneutical engagement with the Qur’an and Islam and its historical location as well as implication in the current moment.)

While a detailed survey of books of and on exegesis of Qur’an can’t be provided and without actual data it is hard to know which of the ‘literalist’, ‘modernist-literalist’ and ‘reformist’ exegesis are engaged with and how popular they are. However, it is pertinent to point that Before Orthodoxy by the great scholar of Islam Shahab Ahmad can give a useful survey to the interested reader to know about the Tafsir cultural and theological project in Islam in its early centuries.

Over the years my own engagement shifted as mentioned earlier from following the text in the literalist interpretation to being skeptical in the vein of the current ‘secular’ critics of religion and then eventually to the present engagement which seeks to bring nuance into reading and making hermeneutical sense of the text. I now feel that the Qur’an has to be understood and engaged with through the theoretical system of context and pretext as formulated by Shahab Ahmad in What is Islam?

This theoretical framework gives one the resources to read not only the Qur’an but also understand Islam as object of historical human experience and truth. Briefly, pretext can refer to tools, philosophies, meditations, experiences, legacies, histories and epistemological tools and methods through which the text of Qur’an can be explained or rendered as the source of hermeneutical meaning and normative values. Reason (Aql) and engagement-through-being (the philosophy of Wahdat-ul-Wajood) are the two mainstays of pretext and the text of Qur’an historically has been explained through, or its explanation subjected to by, dominant Sufi and philosophical strains of Islam.

What is called context can be a bit controversial, given the current moment and turn of events we find ourselves in, as the literalist and more fanatic version of Islam in vogue today will want to erase the historical context, lived experience and the complex socio-cultural engagement and meaning-making processes of the historical reality. But there is no Islam, and in extension, no hermeneutical engagement with Qur’an if the lived experiences of Muslims are written-off.

For the literalists of today, it is only texts and the selective historical traditions which are all there can be to explain Qur’an. From context to a verse or part in Qur’an is meant not only the ‘Sabab-e-Nazul’ (the event for and at which the particular verse or parts were revealed) but also how those verses or the parts have been made sense of and meaning by Muslims throughout history. What forms context and can be legitimately seen as context has become a contested ground among different practices, theologies and beliefs of Islam.

(to be continued)

To get to the meaning and implication of the text of a scripture, the idiom of not only the language, but the whole projects of meaning-making, value extraction, normative and prescriptive codes as well as the socio-cultural complex associated and built around the text of the scripture has to be understood and realized both in reason as well as in feeling.

This matter makes reading scripture – the Qur’an more so because of the charged environment and the turn of modernity and the relation of Islam with modernity – an empathetic matter. And due to that, the activity of reading, comprehending and appealing to its authority (either to proselytize or detract), becomes all the more layered. In light of my own engagement with reading the Qur’an, making sense of the faith and to draw out meaning for myself and to comprehend the religious experience, I have undergone significant phases and shifts. While those changes and shifts can be extraneous to this article, but it has to be mentioned that my reading and engagement with the Qur’an was not always scholarly. For that matter, given my current understanding of the project of locating the text of the Qur’an in the historical and human complex of Islam as an object of experience, my understanding of scripture or its reading can’t be separated from my larger values and perspectives on life.

I started reading the Qur’an through Tafsir at an early stage of life. My first engagement was with Tafsir Maarif-ul-Quran which was composed of Qur’an and Tafsir lectures of the eminent Pakistani Deobandi scholar Mufti Mohammad Shafi. That exegesis is in light of the religious strain which has become the mainstream religious discourse. Access of the social engagement to the exegesis and Qur’an is unfortunately limited to such mainstream discourse of exegesis of Qur’an, which presents often the literalist version of Islam. Thus, engaging with Qur’an also is seen as an extension of that literalist strain of Islam. This is not to call for some kind of ‘critical’ engagement, for the term critical has such loaded connotations that it cannot convey anything meaningful.

Given my current understanding of the project of locating the text of the Qur’an in the historical and human complex of Islam as an object of experience, my understanding of scripture or its reading can’t be separated from my larger values and perspectives on life

I also don’t want to deny the importance of the Tafasir which often are the entry-way into larger engagement with the Qur’an and Islam for those faithful who want to go beyond rituals of worship and want to include a hermeneutical side to their understanding and practice of faith. This kind of Tafasir (taking Maarif-ul-Quran as a model which is a detailed one at 8 volumes) also provides a window to the creedal and theological basis of the religious authorities who now are synonymous with orthodoxy. I have found my engagement with this Tafsir not only my hermeneutical comprehension of the terms, values and dogmas of the current orthodoxy but also an exposure to the structure, message and functional aims of the Qur’an. Yet, I feel that such works leave the hermeneutical engagement with Qur’an (and historical Islam) at best truncated, and at worst, literalist-reductive. (There are other works, some a volume or two and others having more volumes than Maarif-ul-Quran who are referred to in our society but often the variation is in matter of length rather than the nature and form of theological or historical hermeneutical engagement.)

In Pakistan, there are other exegesis involved in the mainstream engagement which can be called modernist in nature, but which at best can be modernist-literalist (that is literalism presented in the language, vocabulary and idiom of modernism), for instance Tafhim-ul-Quran by Maulana Maududi (needs no introduction), or which can be ‘reformist’ in strain of the Tafsir by Amin Ahsan Islahi. (The term reformism/reformist needs a separate treatment in that how it came to be associated with ‘application of reason’ in hermeneutical engagement with the Qur’an and Islam and its historical location as well as implication in the current moment.)

While a detailed survey of books of and on exegesis of Qur’an can’t be provided and without actual data it is hard to know which of the ‘literalist’, ‘modernist-literalist’ and ‘reformist’ exegesis are engaged with and how popular they are. However, it is pertinent to point that Before Orthodoxy by the great scholar of Islam Shahab Ahmad can give a useful survey to the interested reader to know about the Tafsir cultural and theological project in Islam in its early centuries.

What is called context can be a bit controversial, given the current moment and turn of events we find ourselves in, as the literalist version of Islam in vogue today will want to erase the historical context, lived experience, complex socio-cultural engagement and meaning-making processes of the historical reality

Over the years my own engagement shifted as mentioned earlier from following the text in the literalist interpretation to being skeptical in the vein of the current ‘secular’ critics of religion and then eventually to the present engagement which seeks to bring nuance into reading and making hermeneutical sense of the text. I now feel that the Qur’an has to be understood and engaged with through the theoretical system of context and pretext as formulated by Shahab Ahmad in What is Islam?

This theoretical framework gives one the resources to read not only the Qur’an but also understand Islam as object of historical human experience and truth. Briefly, pretext can refer to tools, philosophies, meditations, experiences, legacies, histories and epistemological tools and methods through which the text of Qur’an can be explained or rendered as the source of hermeneutical meaning and normative values. Reason (Aql) and engagement-through-being (the philosophy of Wahdat-ul-Wajood) are the two mainstays of pretext and the text of Qur’an historically has been explained through, or its explanation subjected to by, dominant Sufi and philosophical strains of Islam.

What is called context can be a bit controversial, given the current moment and turn of events we find ourselves in, as the literalist and more fanatic version of Islam in vogue today will want to erase the historical context, lived experience and the complex socio-cultural engagement and meaning-making processes of the historical reality. But there is no Islam, and in extension, no hermeneutical engagement with Qur’an if the lived experiences of Muslims are written-off.

For the literalists of today, it is only texts and the selective historical traditions which are all there can be to explain Qur’an. From context to a verse or part in Qur’an is meant not only the ‘Sabab-e-Nazul’ (the event for and at which the particular verse or parts were revealed) but also how those verses or the parts have been made sense of and meaning by Muslims throughout history. What forms context and can be legitimately seen as context has become a contested ground among different practices, theologies and beliefs of Islam.

(to be continued)