One reflection of the richness of a language is the sophistication of its idioms. Pakhtu, also pronounced as Pashtu, is the mother tongue to nearly 50 million people that includes half the population of Afghanistan, nearly 15 percent that of Pakistan and hundreds of thousands spread in other parts of the world. Pakhtuns are proud of their language and use it for mutual communication among themselves.

Pashto is an ancient east Iranian language with strong Persian influence but distinct in grammar. With such a long history of existence in a region that once formed part of the Golden Age of Islamic Sciences, it is but natural that it conveys in idioms what it has gained in wisdom and acumen.

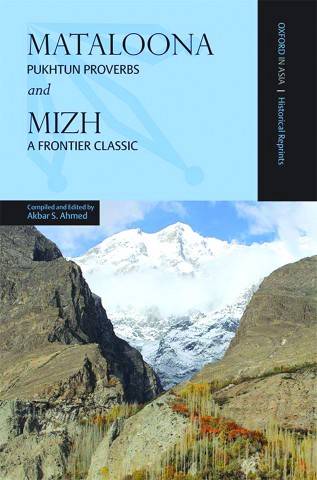

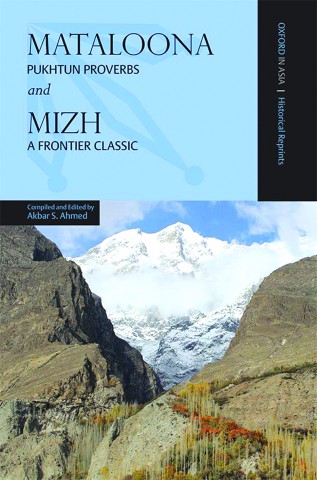

Dr. Akbar Ahmed is currently a professor of International Relations in the American University in Washington and is doing an admirable work in promoting interfaith harmony in the western world. As a member of senior Pakistani bureaucracy, he served as Political Agent in South Waziristan and Orakzai Agencies, and later as a commissioner in Balochistan.

Dr. Akbar is well versed with the Pashto language. In compiling Pakhtu idioms in his book Mataloona, he has done admirable work for the promotion of the language. The book is unique as in addition to translating the selected idioms into English, it has also assembled sayings from other languages that convey the same sense as the corresponding Pashto idioms. This linkage highlights that richness of Pashtu is at par with other more established and known western languages. The significance of the book is evident by the fact that its preface is penned by Sir Olaf Caroe, the author of The Pathans and, perhaps, the most authoritative historian of these people. The idioms prove that the Pakhtuns are as proficient in wielding the pen as the sword or the gun.

Dr. Akbar’s selection of idioms is representative of common Pakhtun’s life over a wide range of activities. Consider, for instance, pearls of wisdom such as “A woman’s place is either home or grave,” “A hint to noble and a kick to the ignoble,” “When man is perplexed, God is beneficent” and many more. These idioms indicate with sufficient clarity that Pashtu idioms depict the psyche and life of its speakers.

Particularly striking is the proverb that says, “The Pakhtun who took revenge after a hundred years said that he took it too quickly.” The proverb accurately depicts the mindset of a Pakhtun who neither forgives an injury done to him nor forgives his enemy, and is willing for an indefinite wait to take his revenge. Combining this wisdom with the message conveyed in another idiom that says “Patience is bitter but its fruit is sweet” tells us why this hardy nation has been able to defeat three world powers in succession in the last 150 years. It also explains the current situation in Afghanistan where US troops think that the two-decade old war has dragged on for long enough but their tormentors, the Pakhtun Taleban, say that their time has not commenced as yet. Pakhtun’s love for freedom in their area and their pursuit for revenge is built in their character. This observation brings us to the second part of the book under review, which is titled ‘Mizh.’

Mizh is a monograph on the relationship between the colonial British government and the Mehsud tribesmen of South Waziristan Agency. It is authored by Mr Evelyn Howell, the British Resident in the Agency in the period 1924-26. It was a critical time in the Indian independence movement when Gandhi’s non-violent tactics shook the foundations of the British Raj on one hand and created an unbridgeable schism between the Hindu and Muslim communities on the other. However, the Mehsuds were oblivious of these momentous happenings and were only concerned about preserving their own freedom and financial privileges. Mr Howell has covered the whole British experience in the Agency from their earliest arrival in 1846 to the end of his own tenure.

Mehsud tribesmen have been in the limelight, for right or wrong reasons, ever since the bulk of al-Qaeda escaped from Afghanistan to the lower three erstwhile FATA agencies, namely Kurram, North Waziristan, and South Waziristan. While the former two regions went relatively quiet, it is South Waziristan and its Mehsud tribes that caused the most trouble to the administration and forces of Pakistan. The region continues to remain restive. The names of places such as Tank, Tangi, Makin, Razmak, Tank, Ladha, Jandola, Wana, Shakai and Sararogha have been mentioned in the Mizh as trouble spots. These are the same names that have been in news for being troublesome in the two decades since 9/11 events, proving that little has changed in the way Mehsuds operate.

The advantages that the Mehsuds have enjoyed are their sanctuaries in Afghanistan, difficult terrain of their country, barren environment, natural fighting abilities and flair for independence. Add to these the fact that they respect the agreements made by them only when under duress. It is for this reason that, like all predatory animals, they only fear a superior force and hold weakness in contempt. One sign of their cantankerous behavior is their toxic relationship with all their neighbors.

Evelyn has described the British relationship with Mehsuds in chronological details. The British first tried to govern Waziristan but soon realized the futility of the exercise. Several British political and military officers were murdered or killed in action. In 1850 and 1917 specially, the British troops were attacked with a large number of casualties. Of the 34 British Political Agents, four were murdered and one committed suicide. The British could neither disarm the Mehsud, nor levy any taxes nor apply any laws. The British made large payments in the shape of cash allowances and Khasadar emoluments but could not subdue them. Mr Howell writes, with some justification, that the rapacity of the Mehsud is insatiable. Let it be added here that the colonial administrator understood this trait well and their own level of rapacity was reflected in the behavior of these untamed tribesmen.

The British finally settled on merely managing the Agency through Maliks. The tribesmen accepted the right to live, trade and work in the settled areas but denied the establishment of a legal order in their own areas. This was nothing sort of extortion that the Mehsud were successful in this practice till our time when their area has been declared a settled district of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province.

An enduring aspect of Mehsud strategy is their creative use of the Durand Line for which they had scant respect. They committed crimes in the settled districts and found sanctuaries amongst their kin in Afghanistan across the border. They very adroitly put this practice to use during the Soviet invasion. They again put the Durand Line to dual use during the US invasion when some elements of the tribesmen targeted the Pakistani forces and crossed over to Afghanistan for security whereas other elements attacked the US forces in Afghanistan but crossed over to Pakistan to recuperate.

However, it also is a fact that much as the ferocious Mehsuds have been romanticized by outsiders, they can be quite tame if they are separated from their environment proving the truth of the idiom given in the Mataloona that says, “Even an ant is brave in its home.” Mehsuds find employments in Dubai and Karachi where their ferociousness is tamed by a single person from law enforcement agencies. Another indication of their being tamed the Pakhtun Tahaffuz Movement that is active in certain parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa but in Karachi, whose police is the source of their original grievance due to the unjust murder of Naqibullah Mehsud, it has no clout or nuisance value.

A study paper by Mr. Matthew W. Williams of DoD authored in May 2005 and intriguingly titled “A monograph on the British colonial experience in Waziristan and its applicability to current operations” concludes that, “The U.S. should shape the environment as discreetly as possible and let the Pakistani government deny and disrupt Al-Qaeda and Taliban activities in Waziristan. The British colonial experience demonstrated overt military operations do not guarantee any success in Waziristan.”

Obviously, this later monograph refers to the Malik and the Lungi system. The British system however, as narrated in Mizh, led to Maliks being perceived as operatives of the infidels with several of them being murdered. Now, perhaps for the first time in history since Alexander the Great, Pakistani forces have been able to establish their control over the Mehsuds, beating these formidable tribesmen in their own area and game.

The US report, strangely, makes no mention of Mizh. It is hard to believe that the US author had no access to the British report.

Now that the world is expecting peace to prevail in Afghanistan, Mizh is a timely reminder to deter future foreign aggression in this part of the world.

The writer retired as a Group Captain from PAF and is now a software engineer. He lives in Islamabad and writes on social and historical issues. He can be reached at parvezmahmood53@gmail.com

Pashto is an ancient east Iranian language with strong Persian influence but distinct in grammar. With such a long history of existence in a region that once formed part of the Golden Age of Islamic Sciences, it is but natural that it conveys in idioms what it has gained in wisdom and acumen.

Dr. Akbar Ahmed is currently a professor of International Relations in the American University in Washington and is doing an admirable work in promoting interfaith harmony in the western world. As a member of senior Pakistani bureaucracy, he served as Political Agent in South Waziristan and Orakzai Agencies, and later as a commissioner in Balochistan.

Dr. Akbar is well versed with the Pashto language. In compiling Pakhtu idioms in his book Mataloona, he has done admirable work for the promotion of the language. The book is unique as in addition to translating the selected idioms into English, it has also assembled sayings from other languages that convey the same sense as the corresponding Pashto idioms. This linkage highlights that richness of Pashtu is at par with other more established and known western languages. The significance of the book is evident by the fact that its preface is penned by Sir Olaf Caroe, the author of The Pathans and, perhaps, the most authoritative historian of these people. The idioms prove that the Pakhtuns are as proficient in wielding the pen as the sword or the gun.

Dr. Akbar’s selection of idioms is representative of common Pakhtun’s life over a wide range of activities. Consider, for instance, pearls of wisdom such as “A woman’s place is either home or grave,” “A hint to noble and a kick to the ignoble,” “When man is perplexed, God is beneficent” and many more. These idioms indicate with sufficient clarity that Pashtu idioms depict the psyche and life of its speakers.

Particularly striking is the proverb that says, “The Pakhtun who took revenge after a hundred years said that he took it too quickly.” The proverb accurately depicts the mindset of a Pakhtun who neither forgives an injury done to him nor forgives his enemy, and is willing for an indefinite wait to take his revenge. Combining this wisdom with the message conveyed in another idiom that says “Patience is bitter but its fruit is sweet” tells us why this hardy nation has been able to defeat three world powers in succession in the last 150 years. It also explains the current situation in Afghanistan where US troops think that the two-decade old war has dragged on for long enough but their tormentors, the Pakhtun Taleban, say that their time has not commenced as yet. Pakhtun’s love for freedom in their area and their pursuit for revenge is built in their character. This observation brings us to the second part of the book under review, which is titled ‘Mizh.’

Mizh is a monograph on the relationship between the colonial British government and the Mehsud tribesmen of South Waziristan Agency. It is authored by Mr Evelyn Howell, the British Resident in the Agency in the period 1924-26. It was a critical time in the Indian independence movement when Gandhi’s non-violent tactics shook the foundations of the British Raj on one hand and created an unbridgeable schism between the Hindu and Muslim communities on the other. However, the Mehsuds were oblivious of these momentous happenings and were only concerned about preserving their own freedom and financial privileges. Mr Howell has covered the whole British experience in the Agency from their earliest arrival in 1846 to the end of his own tenure.

Mehsud tribesmen have been in the limelight, for right or wrong reasons, ever since the bulk of al-Qaeda escaped from Afghanistan to the lower three erstwhile FATA agencies, namely Kurram, North Waziristan, and South Waziristan. While the former two regions went relatively quiet, it is South Waziristan and its Mehsud tribes that caused the most trouble to the administration and forces of Pakistan. The region continues to remain restive. The names of places such as Tank, Tangi, Makin, Razmak, Tank, Ladha, Jandola, Wana, Shakai and Sararogha have been mentioned in the Mizh as trouble spots. These are the same names that have been in news for being troublesome in the two decades since 9/11 events, proving that little has changed in the way Mehsuds operate.

The advantages that the Mehsuds have enjoyed are their sanctuaries in Afghanistan, difficult terrain of their country, barren environment, natural fighting abilities and flair for independence. Add to these the fact that they respect the agreements made by them only when under duress. It is for this reason that, like all predatory animals, they only fear a superior force and hold weakness in contempt. One sign of their cantankerous behavior is their toxic relationship with all their neighbors.

Evelyn has described the British relationship with Mehsuds in chronological details. The British first tried to govern Waziristan but soon realized the futility of the exercise. Several British political and military officers were murdered or killed in action. In 1850 and 1917 specially, the British troops were attacked with a large number of casualties. Of the 34 British Political Agents, four were murdered and one committed suicide. The British could neither disarm the Mehsud, nor levy any taxes nor apply any laws. The British made large payments in the shape of cash allowances and Khasadar emoluments but could not subdue them. Mr Howell writes, with some justification, that the rapacity of the Mehsud is insatiable. Let it be added here that the colonial administrator understood this trait well and their own level of rapacity was reflected in the behavior of these untamed tribesmen.

The British finally settled on merely managing the Agency through Maliks. The tribesmen accepted the right to live, trade and work in the settled areas but denied the establishment of a legal order in their own areas. This was nothing sort of extortion that the Mehsud were successful in this practice till our time when their area has been declared a settled district of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province.

An enduring aspect of Mehsud strategy is their creative use of the Durand Line for which they had scant respect. They committed crimes in the settled districts and found sanctuaries amongst their kin in Afghanistan across the border. They very adroitly put this practice to use during the Soviet invasion. They again put the Durand Line to dual use during the US invasion when some elements of the tribesmen targeted the Pakistani forces and crossed over to Afghanistan for security whereas other elements attacked the US forces in Afghanistan but crossed over to Pakistan to recuperate.

However, it also is a fact that much as the ferocious Mehsuds have been romanticized by outsiders, they can be quite tame if they are separated from their environment proving the truth of the idiom given in the Mataloona that says, “Even an ant is brave in its home.” Mehsuds find employments in Dubai and Karachi where their ferociousness is tamed by a single person from law enforcement agencies. Another indication of their being tamed the Pakhtun Tahaffuz Movement that is active in certain parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa but in Karachi, whose police is the source of their original grievance due to the unjust murder of Naqibullah Mehsud, it has no clout or nuisance value.

A study paper by Mr. Matthew W. Williams of DoD authored in May 2005 and intriguingly titled “A monograph on the British colonial experience in Waziristan and its applicability to current operations” concludes that, “The U.S. should shape the environment as discreetly as possible and let the Pakistani government deny and disrupt Al-Qaeda and Taliban activities in Waziristan. The British colonial experience demonstrated overt military operations do not guarantee any success in Waziristan.”

Obviously, this later monograph refers to the Malik and the Lungi system. The British system however, as narrated in Mizh, led to Maliks being perceived as operatives of the infidels with several of them being murdered. Now, perhaps for the first time in history since Alexander the Great, Pakistani forces have been able to establish their control over the Mehsuds, beating these formidable tribesmen in their own area and game.

The US report, strangely, makes no mention of Mizh. It is hard to believe that the US author had no access to the British report.

Now that the world is expecting peace to prevail in Afghanistan, Mizh is a timely reminder to deter future foreign aggression in this part of the world.

The writer retired as a Group Captain from PAF and is now a software engineer. He lives in Islamabad and writes on social and historical issues. He can be reached at parvezmahmood53@gmail.com