Ali ibn Nafi, better known as Ziryab (Black Bird), is a fascinating figure from the Middle Ages. Shrouded in some mystery, he continues to exert a powerful and enduring influence on many facets of our lives. He revolutionized instrumental music, dress codes, culinary habits, the use of the tableware and eating practices that have outlived him, even though most of us are not aware of his contributions made long ago.

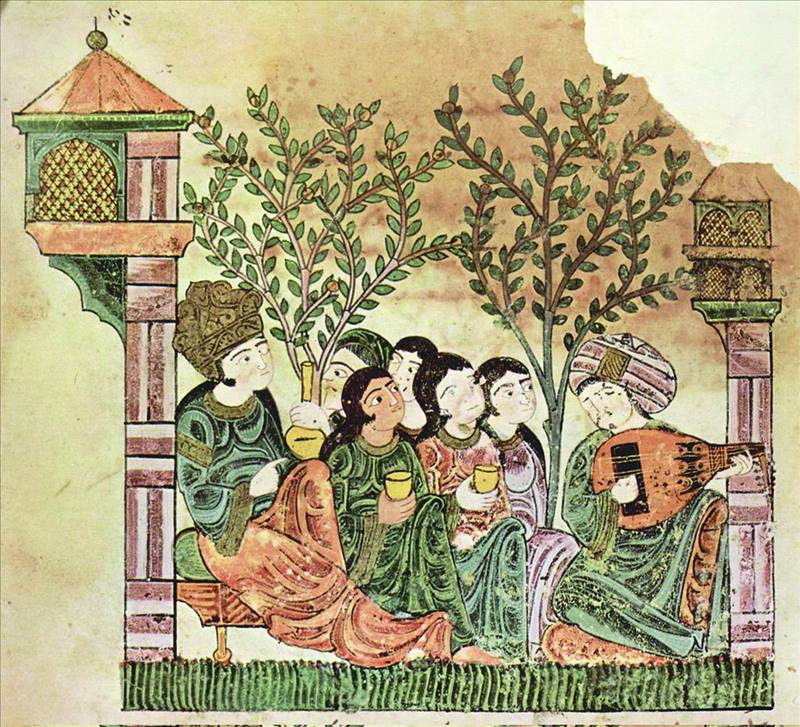

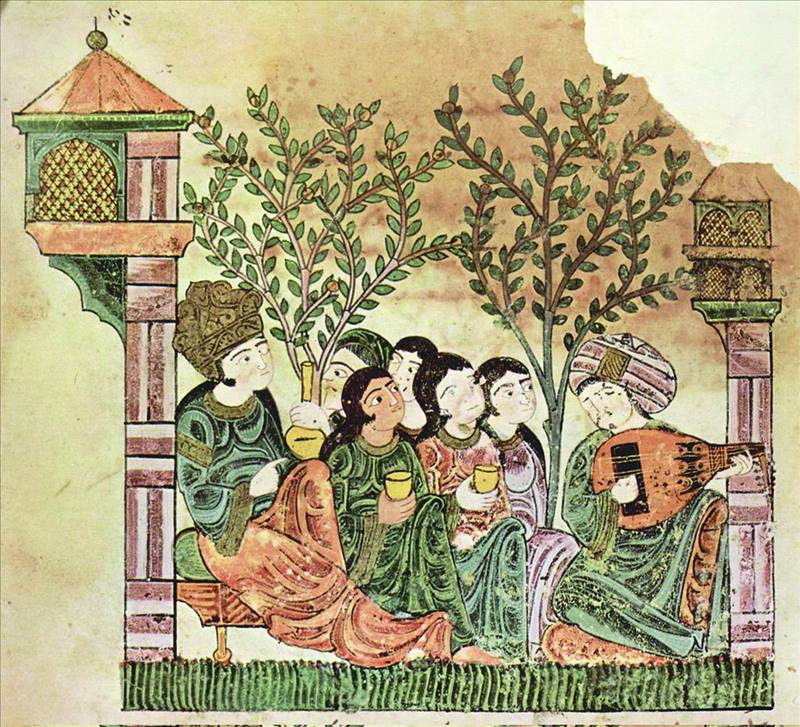

Ziryab lived in the eighth century, more than 12 hundred years ago, at a time when Islamic civilization was at its zenith. Both Abbasid Bagdad and Umayyad Cordoba had evolved into great centres of culture and civilization, ushering in a golden age that saw fluorescence of hard sciences as well as fine arts. Baghdad was ruled by the storied Caliph Harun Al-Rashid from 786 to 809 AD, while Cordoba, capital of Islamic Spain, blossomed under Amir Abdur Rehman II. Interestingly, the two capitals were seats of adversarial dynasties that competed to draw to their courts most talented, gifted musicians, artists and learned luminaries.

Nicknamed “black bird” because of his dark complexion and ability to sing beautifully, details of Ziryab’s early life are scant and somewhat murky, as much of the original information has not survived. Mostly unknown to European scholars, some Western authors have only lately been researching his life and contributions. According to Dwight Reynolds, a professor of Religious Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, all the available information about him is believed to have been drawn from a single source, Kitab Ziryab, appearing some two hundred years after his death. The original text has not survived, only brief extracts cited by later authors are accessible to us today.

It remains uncertain where Ziryab was born. His birthplace has been identified variously as Iraq, Persia, or North Africa, and he is believed to have been born in 789 AD. Harun al-Rashid was a great connoisseur of music and poetry, and his court in Baghdad had become a dazzling hub to which a galaxy of most talented artists from around the world were drawn. Ibrahim Ishaq al-Mawsili (766-889) was the chief musician at the courts of Harun al-Rashid and later his son, Mamun (786-833), as was his father Ibrahim al-Mawsili before him. Ziryab seems to have found a niche for himself at the Abbasid court and became one of many pupils of Ishaq al-Mawsili. He learnt his music lessons so well that he soon started to outshine his celebrated teacher.

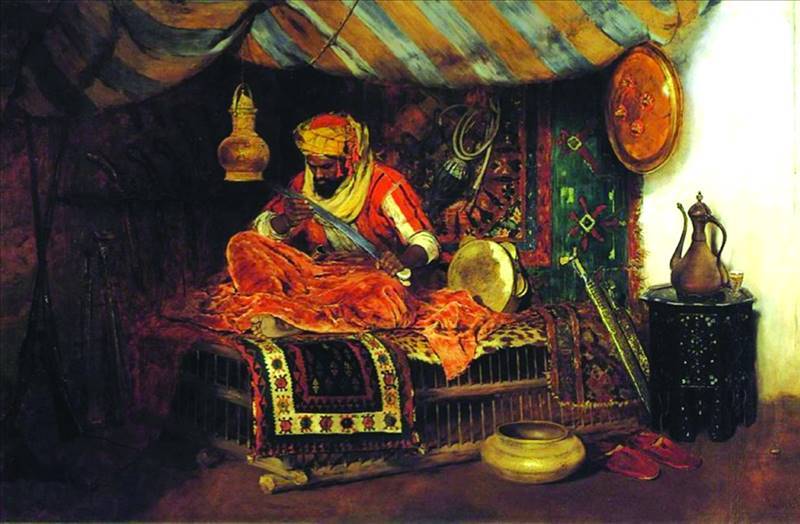

A bizarre story is told about the relationship of the teacher with his student. Ziryab mastered some of the signature masterpieces in the repertoire of his teacher, Mawsili, without his knowledge or permission. By this time, Ziryab’s reputation for brilliance had reached the Caliph who asked that the artist be invited to perform for him. Ziryab sang a song that he had composed himself, using a lute that he had built. The ethereal quality of his presentation stunned the Caliph and his courtiers. He had excelled even his iconic teacher, al-Mawsili. Eventually, the situation became so threatening to Mawsili that he demanded that his pupil either leave Baghdad for some far-off land or be destroyed.

Aware of the power and influence of al-Mawsili, Ziryab followed the prudent course and left the capital in the middle of the night, setting out toward North Africa. However, the accounts of his precipitous departure from Baghdad differ. Another version suggests that, in fact, he outlived the reign of Harun al-Rashid and left during the rule of his son, Mamun. There is also disagreement whether Ziryab spent some time serving at the court of the Aghlabid Emir, Ziyadat Allah, in North Africa. The region, comprising Tunis and Algeria, was at the time ruled by an Arab dynasty (800-909) that had conquered Sicily and Southern Italy. There is agreement, however, that Ziryab arrived at Cordoba, the fast-growing capital of Andalusia, in 822 during the reign of Amir Abdur Rehman II (792–852), the fourth Umayyad ruler of Cordoba. The city was soon to become the envy of Europe. The Emir himself was an exquisitely cultured and cultivated man. He had adorned his capital with palaces, gardens, and mosques, making it a colorful cosmopolitan city.

The Amir was also a great admirer of fine arts, music, poetry and is reputed to have been a poet himself and was delighted to have Ziryab associated with his court. He became so enamoured of the music maestro that he would often invite him to share his meals. He loved to hear the exotic stories Ziryab told him from his days in the Baghdad of the Arabian Nights.

The famed British orientalist, Stanley Lane-Pool, in his book The Story of the Moors in Spain, noted that “Ziryab knew more than a thousand songs by heart, each with its separate tune. He added a fifth string to the lute and his style of playing was so unique that people who heard him would bear to hear no one else afterwards.”

Ziryab, perhaps the most talented artist of classic Arabic music in a millennium, excelled in many other disciplines besides composition of music and songs. He transformed the artistic and intellectual landscape of the Muslim Spain, founding the first music school in Cordoba that trained sons and daughter of the rich as well as the poor. It is difficult to capture in this brief article the innovations that Ziryab instituted during his tenure at Cordoba. He introduced a novel fifth pair of strings to the lute (barbet in Persian, oud in Arabic) that evolved into modern-day guitar, making it more melodious. He popularized sophisticated, refined dining practices to replace the rather coarse, dull customs in vogue. Ziryab mandated that the meals be served in several courses, starting with soup and ending with dessert and dried fruits, practices later adopted by European society, that have survived to this day.

Robert Lebling, an American author and literary critic, in his scholarly essay in Saudi Aramco World has recounted the practices that are credited to Ziryab that changed the culture norms of the Andalusian royal court forever. The sartorial practices in Cordoba had not changed for ages, people dressed either for winter or summer. Ziryab persuaded them to adapt to wearing a range of clothing suited to shifting weather conditions. He focused his attention on female needs as well, starting beauty parlours in today’s parlance. He brought astrologers from India and Jewish physicians to Cordoba. Indians also brought with them the game of chess which became popular with the masses and spread to Europe.

Amir Abdur Rehman II, Ziryab’s mentor and friend, died in 852 after ruling for 30 glorious years. Five years later, Ziryab followed him in death. By that time, the Emirate of Andalusia was on a firm path to stability and prosperity. It reached its zenith during the reign of Caliph Abdur Rehman III (912-929), the eighth and the greatest Umayyad ruler and the first Caliph. While the country scaled unprecedented new heights, it never produced another “black bird” of Cordoba.

The writer is a former assistant professor Harvard Medical School and a retired Health Scientist Administrator, US National Institutes of Health

Ziryab lived in the eighth century, more than 12 hundred years ago, at a time when Islamic civilization was at its zenith. Both Abbasid Bagdad and Umayyad Cordoba had evolved into great centres of culture and civilization, ushering in a golden age that saw fluorescence of hard sciences as well as fine arts. Baghdad was ruled by the storied Caliph Harun Al-Rashid from 786 to 809 AD, while Cordoba, capital of Islamic Spain, blossomed under Amir Abdur Rehman II. Interestingly, the two capitals were seats of adversarial dynasties that competed to draw to their courts most talented, gifted musicians, artists and learned luminaries.

Nicknamed “black bird” because of his dark complexion and ability to sing beautifully, details of Ziryab’s early life are scant and somewhat murky, as much of the original information has not survived. Mostly unknown to European scholars, some Western authors have only lately been researching his life and contributions. According to Dwight Reynolds, a professor of Religious Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, all the available information about him is believed to have been drawn from a single source, Kitab Ziryab, appearing some two hundred years after his death. The original text has not survived, only brief extracts cited by later authors are accessible to us today.

It remains uncertain where Ziryab was born. His birthplace has been identified variously as Iraq, Persia, or North Africa, and he is believed to have been born in 789 AD. Harun al-Rashid was a great connoisseur of music and poetry, and his court in Baghdad had become a dazzling hub to which a galaxy of most talented artists from around the world were drawn. Ibrahim Ishaq al-Mawsili (766-889) was the chief musician at the courts of Harun al-Rashid and later his son, Mamun (786-833), as was his father Ibrahim al-Mawsili before him. Ziryab seems to have found a niche for himself at the Abbasid court and became one of many pupils of Ishaq al-Mawsili. He learnt his music lessons so well that he soon started to outshine his celebrated teacher.

He introduced a novel fifth pair of strings to the lute (barbet in Persian, oud in Arabic) that evolved into modern-day guitar, making it more melodious. He popularized sophisticated, refined dining practices to replace the rather coarse, dull customs in vogue

A bizarre story is told about the relationship of the teacher with his student. Ziryab mastered some of the signature masterpieces in the repertoire of his teacher, Mawsili, without his knowledge or permission. By this time, Ziryab’s reputation for brilliance had reached the Caliph who asked that the artist be invited to perform for him. Ziryab sang a song that he had composed himself, using a lute that he had built. The ethereal quality of his presentation stunned the Caliph and his courtiers. He had excelled even his iconic teacher, al-Mawsili. Eventually, the situation became so threatening to Mawsili that he demanded that his pupil either leave Baghdad for some far-off land or be destroyed.

Aware of the power and influence of al-Mawsili, Ziryab followed the prudent course and left the capital in the middle of the night, setting out toward North Africa. However, the accounts of his precipitous departure from Baghdad differ. Another version suggests that, in fact, he outlived the reign of Harun al-Rashid and left during the rule of his son, Mamun. There is also disagreement whether Ziryab spent some time serving at the court of the Aghlabid Emir, Ziyadat Allah, in North Africa. The region, comprising Tunis and Algeria, was at the time ruled by an Arab dynasty (800-909) that had conquered Sicily and Southern Italy. There is agreement, however, that Ziryab arrived at Cordoba, the fast-growing capital of Andalusia, in 822 during the reign of Amir Abdur Rehman II (792–852), the fourth Umayyad ruler of Cordoba. The city was soon to become the envy of Europe. The Emir himself was an exquisitely cultured and cultivated man. He had adorned his capital with palaces, gardens, and mosques, making it a colorful cosmopolitan city.

The Amir was also a great admirer of fine arts, music, poetry and is reputed to have been a poet himself and was delighted to have Ziryab associated with his court. He became so enamoured of the music maestro that he would often invite him to share his meals. He loved to hear the exotic stories Ziryab told him from his days in the Baghdad of the Arabian Nights.

The famed British orientalist, Stanley Lane-Pool, in his book The Story of the Moors in Spain, noted that “Ziryab knew more than a thousand songs by heart, each with its separate tune. He added a fifth string to the lute and his style of playing was so unique that people who heard him would bear to hear no one else afterwards.”

Ziryab, perhaps the most talented artist of classic Arabic music in a millennium, excelled in many other disciplines besides composition of music and songs. He transformed the artistic and intellectual landscape of the Muslim Spain, founding the first music school in Cordoba that trained sons and daughter of the rich as well as the poor. It is difficult to capture in this brief article the innovations that Ziryab instituted during his tenure at Cordoba. He introduced a novel fifth pair of strings to the lute (barbet in Persian, oud in Arabic) that evolved into modern-day guitar, making it more melodious. He popularized sophisticated, refined dining practices to replace the rather coarse, dull customs in vogue. Ziryab mandated that the meals be served in several courses, starting with soup and ending with dessert and dried fruits, practices later adopted by European society, that have survived to this day.

Robert Lebling, an American author and literary critic, in his scholarly essay in Saudi Aramco World has recounted the practices that are credited to Ziryab that changed the culture norms of the Andalusian royal court forever. The sartorial practices in Cordoba had not changed for ages, people dressed either for winter or summer. Ziryab persuaded them to adapt to wearing a range of clothing suited to shifting weather conditions. He focused his attention on female needs as well, starting beauty parlours in today’s parlance. He brought astrologers from India and Jewish physicians to Cordoba. Indians also brought with them the game of chess which became popular with the masses and spread to Europe.

Amir Abdur Rehman II, Ziryab’s mentor and friend, died in 852 after ruling for 30 glorious years. Five years later, Ziryab followed him in death. By that time, the Emirate of Andalusia was on a firm path to stability and prosperity. It reached its zenith during the reign of Caliph Abdur Rehman III (912-929), the eighth and the greatest Umayyad ruler and the first Caliph. While the country scaled unprecedented new heights, it never produced another “black bird” of Cordoba.

The writer is a former assistant professor Harvard Medical School and a retired Health Scientist Administrator, US National Institutes of Health