Death comes to all, common place in its inevitability and is always accompanied by profound and lingering grief. But certain deaths and accompanying mourning can be more complicated.

The latest escalation of the Sino-India conflict in Galwan Valley along the poorly demarcated Line of Actual Control in the Ladakh region has spawned a flurry of policy debates and articles, as well as attracted the attention of zealous patriots from India and Pakistan. What is missing from these grand narratives mired in geo-strategic speculation or sometimes nationalist jingoism is the mention of the soldiers themselves. The body count is repeated ad nauseam as are the peculiarities of this battle that lasted close to six hours in near-total darkness where young men attempted to bludgeon each other to death with bare hands, iron rods and stones. Beyond this, very few reports discuss the visceral experience of battle, such as the build-up of panic in these young bodies in the minutes leading up to the clash, the crack of the first blow or the terrible meshing together of limbs in those dark moments where comrade and foe became indistinguishable. Reports fail to mention smells, the stench of warm blood, sweat and fear. Absent also is any allusion to sounds, of shallow breaths of air gulped down at high altitudes, of sickening thuds that emanate from repeated blows to the body or of cries for help as soldiers lay wounded or fell to their deaths from the narrow Himalayan ridge. These details of combat are glossed over because they are irrelevant to strategic interest analyses and perhaps unsettling for glory narratives that are easier to paint on bodies that embrace death bravely and willingly.

This article is not about glory or strategy but is a more intimate exploration of war, the loss and suffering of families left bereft. In this article I stay with the grief, the wretchedness of loss and the permanence of rupture that families experience in the aftermath of combat.

During 2014 and 2015, I spent over a year in villages of Chakwal with serving and retired soldiers, and the families of shuhada of the Pakistan Military. Ghosts of young men who once roamed in these spaces appear in the speech of the living and in village landscapes that are overrun with memorials to them, both physical and those that linger in space and haunt the air. In a village space where most people cannot accurately recall their own age, where time and space seem suspended, there is an almost uncanny remembrance of the son’s death, sometimes down to the day and time, the unit he was in and his military enrolment number. Family recollections linger over the moment when the phone rang and the father, or the brother picked up the phone and life as they knew it changed forever. Families know that these phone calls can come, for they are aware that their sons are posted in potentially hostile terrains, and many lived in dread. The military funeral is a grand event, and villagers cite the sohni and zabardast parade, the impressive gun salute and the large numbers of people coming from afar to watch. Video recordings by families of these tightly choreographed ceremonies depict a mix of ritualized imagery alongside uncontrolled raw pain.

Every day, ceaseless mourning begins once the military trucks leave and the family struggles to come to terms with loss. Imran died in Swat, only three months after recruitment. His father’s drooping figure walking to his son’s grave every day is a common sight in the village. According to villagers he has not recovered from the loss and “has taken it to heart. He has not thought about it from the other angle [of shahadat]. If he thinks from this angle, that shahadat has its own position, reputation, then he might have got some relief. [But] He is (…) only thinking (…), that his son is no more.”

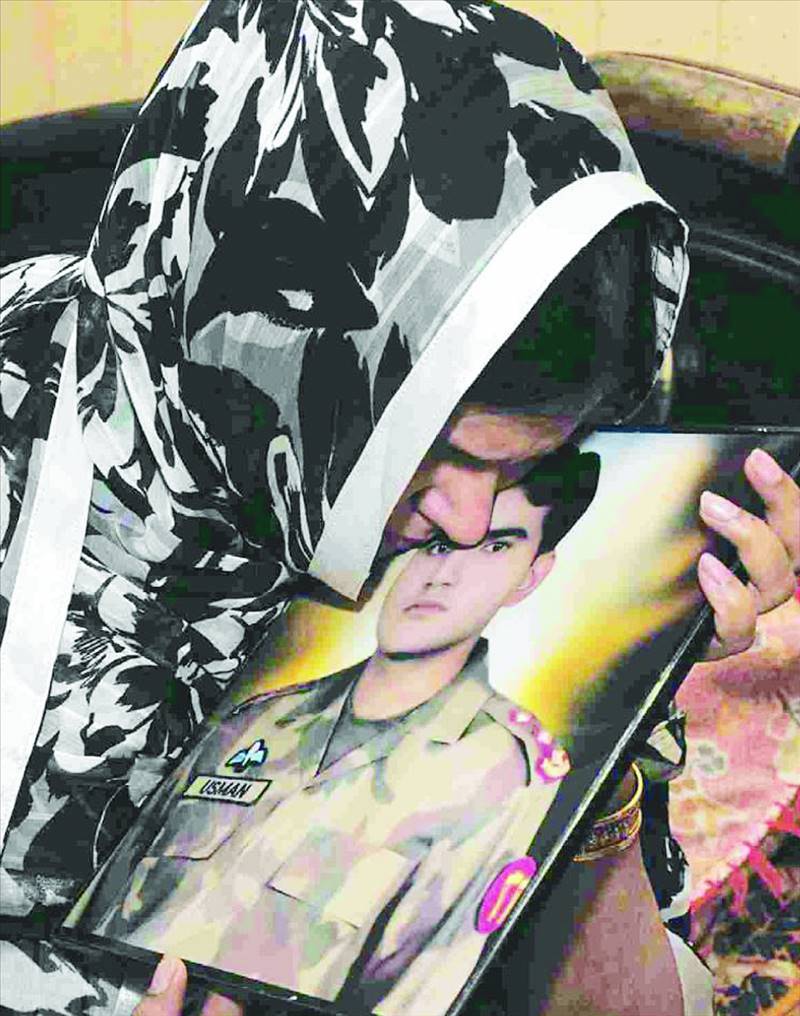

Sajjida, whose son died in Wana, weeps as she rocked back and forth, two photographs of her son in her hand; one in army uniform and another taken at his wedding, six months before his death. Her vaen (a Punjabi mourning ritual) is slow, mournful and melodic, and she asked for death for herself so she could be with him and not feel pain. Sajida cries every time her sons’s name comes up, despite the oft repeated saying shaheedon ki maan roya nahi karti (Mothers of martyrs don’t cry). “I can’t help it (crying). You can lock someone up in a steel cage, but she still can’t help it. As for my son, it is fate, even if I try, it [his death] will happen. I tell myself it was his fate, this shaheedi, even then my tears don’t stop.”

Houses of deceased soldiers are often marked with the name of the martyr and his father, and framed pictures of the dead son including one in his army uniform (recruitry ki photo – a photograph taken on military graduation day) adorn the rooms. The presence of the dead is most marked by their absence in spaces which had earlier resonated with their being, such as the doorway the beloved son used to walk through when he came home on leave or the courtyard where he would sit on the charpai and eat peanuts. A mother kept staring at a fixed spot on the floor, the spot where she told me her son used to put his army boots when he came home on leave. There were no boots there today, yet as she spoke of her son her eyes stared fixedly at that space. Grief is palpable not just in spoken word but also in physical spaces where affective residues linger and defy easy or simple closure. Family members speak of shahadat and willing sacrifice and yet the rawness of grief and sense of terrible loss seemed to hang over these spaces like thick smoke. Unable to find solace in the narrative of shahadat and sacrifice, these men and women continue to grieve for sons who died in wars and terrains far from home.

I am struck by the similarity in scenes captured on the other side of border as the bodies of the 20 soldiers from Galwan valley arrive in Indian villages. A BBC Urdu article published on June 20, carries this haunting quote from a mother in Bihar. “Apne bete ko kho dene se kahain behtaar tha ke wo rookhi sookhi kha kar ghurbat mein hi ghuzara kar letien” (It would have been better to eat plain bread and remain in poverty than to lose our son). Most families that send their son into service come from impoverished regions and like most militaries of the world, it is economic desperation that sustains a ready supply of military labour. When all is said and done, it is for material needs that the tribute to the nation is offered. This is what the mother alludes to when she weighs in on the decision to send her son into military service. Her words echo those I heard from a mother of a soldier in Chakwal, “Money has no value, agar puttar nahio labda (if you can’t find your son). If he had not become a naukar (gone to serve in the military) he would not be a shaheed and would be alive today.” The BBC Urdu news report on the Galwan incident also mentions devastated Indian fathers, one in particular who has been in a state of shock and has not uttered a word since the dreaded phone call arrived announcing his son’s death. Like the stories in Pakistan, these are stories of grief that refuse to follow script; they flow along like tears, unhindered and unchecked, even as parallel scripts of pride and sacrifice remain intact.

In these villages, in Pakistan and in India, the suffering caused by military death shifts between the private and public realms. These are repertoires of grief obscured by the politics of sacrifice and drowned under more amplified appeals to nationalism. What may we learn if we were to not appropriate these stories, not throw slogans or jingoism at them and not filter loss through the colour of a uniform or flag. What may we learn if we paid attention to the muffled sound of wailing, mixing with yet distinct from the stories of pride and resolute sacrifice for the nation. And perhaps more fundamental, what may we learn if we recognized the sameness in suffering and commonalities of the experience of war across fiercely contested borders.

The writer is a feminist practitioner, trainer, and researcher associated with the field of gender, masculinities, and violence. Excerpts have been taken from the author’s book ‘Dying to Serve, Militarism, Affect and the Politics of Sacrifice in the Pakistan Army’ published by Stanford University Press in 2020

The latest escalation of the Sino-India conflict in Galwan Valley along the poorly demarcated Line of Actual Control in the Ladakh region has spawned a flurry of policy debates and articles, as well as attracted the attention of zealous patriots from India and Pakistan. What is missing from these grand narratives mired in geo-strategic speculation or sometimes nationalist jingoism is the mention of the soldiers themselves. The body count is repeated ad nauseam as are the peculiarities of this battle that lasted close to six hours in near-total darkness where young men attempted to bludgeon each other to death with bare hands, iron rods and stones. Beyond this, very few reports discuss the visceral experience of battle, such as the build-up of panic in these young bodies in the minutes leading up to the clash, the crack of the first blow or the terrible meshing together of limbs in those dark moments where comrade and foe became indistinguishable. Reports fail to mention smells, the stench of warm blood, sweat and fear. Absent also is any allusion to sounds, of shallow breaths of air gulped down at high altitudes, of sickening thuds that emanate from repeated blows to the body or of cries for help as soldiers lay wounded or fell to their deaths from the narrow Himalayan ridge. These details of combat are glossed over because they are irrelevant to strategic interest analyses and perhaps unsettling for glory narratives that are easier to paint on bodies that embrace death bravely and willingly.

This article is not about glory or strategy but is a more intimate exploration of war, the loss and suffering of families left bereft. In this article I stay with the grief, the wretchedness of loss and the permanence of rupture that families experience in the aftermath of combat.

The presence of the dead is most marked by their absence in spaces which had earlier resonated with their being, such as the doorway the beloved son used to walk through when he came home on leave or the courtyard where he would sit on the charpai and eat peanuts

During 2014 and 2015, I spent over a year in villages of Chakwal with serving and retired soldiers, and the families of shuhada of the Pakistan Military. Ghosts of young men who once roamed in these spaces appear in the speech of the living and in village landscapes that are overrun with memorials to them, both physical and those that linger in space and haunt the air. In a village space where most people cannot accurately recall their own age, where time and space seem suspended, there is an almost uncanny remembrance of the son’s death, sometimes down to the day and time, the unit he was in and his military enrolment number. Family recollections linger over the moment when the phone rang and the father, or the brother picked up the phone and life as they knew it changed forever. Families know that these phone calls can come, for they are aware that their sons are posted in potentially hostile terrains, and many lived in dread. The military funeral is a grand event, and villagers cite the sohni and zabardast parade, the impressive gun salute and the large numbers of people coming from afar to watch. Video recordings by families of these tightly choreographed ceremonies depict a mix of ritualized imagery alongside uncontrolled raw pain.

Every day, ceaseless mourning begins once the military trucks leave and the family struggles to come to terms with loss. Imran died in Swat, only three months after recruitment. His father’s drooping figure walking to his son’s grave every day is a common sight in the village. According to villagers he has not recovered from the loss and “has taken it to heart. He has not thought about it from the other angle [of shahadat]. If he thinks from this angle, that shahadat has its own position, reputation, then he might have got some relief. [But] He is (…) only thinking (…), that his son is no more.”

Sajjida, whose son died in Wana, weeps as she rocked back and forth, two photographs of her son in her hand; one in army uniform and another taken at his wedding, six months before his death. Her vaen (a Punjabi mourning ritual) is slow, mournful and melodic, and she asked for death for herself so she could be with him and not feel pain. Sajida cries every time her sons’s name comes up, despite the oft repeated saying shaheedon ki maan roya nahi karti (Mothers of martyrs don’t cry). “I can’t help it (crying). You can lock someone up in a steel cage, but she still can’t help it. As for my son, it is fate, even if I try, it [his death] will happen. I tell myself it was his fate, this shaheedi, even then my tears don’t stop.”

Houses of deceased soldiers are often marked with the name of the martyr and his father, and framed pictures of the dead son including one in his army uniform (recruitry ki photo – a photograph taken on military graduation day) adorn the rooms. The presence of the dead is most marked by their absence in spaces which had earlier resonated with their being, such as the doorway the beloved son used to walk through when he came home on leave or the courtyard where he would sit on the charpai and eat peanuts. A mother kept staring at a fixed spot on the floor, the spot where she told me her son used to put his army boots when he came home on leave. There were no boots there today, yet as she spoke of her son her eyes stared fixedly at that space. Grief is palpable not just in spoken word but also in physical spaces where affective residues linger and defy easy or simple closure. Family members speak of shahadat and willing sacrifice and yet the rawness of grief and sense of terrible loss seemed to hang over these spaces like thick smoke. Unable to find solace in the narrative of shahadat and sacrifice, these men and women continue to grieve for sons who died in wars and terrains far from home.

I am struck by the similarity in scenes captured on the other side of border as the bodies of the 20 soldiers from Galwan valley arrive in Indian villages. A BBC Urdu article published on June 20, carries this haunting quote from a mother in Bihar. “Apne bete ko kho dene se kahain behtaar tha ke wo rookhi sookhi kha kar ghurbat mein hi ghuzara kar letien” (It would have been better to eat plain bread and remain in poverty than to lose our son). Most families that send their son into service come from impoverished regions and like most militaries of the world, it is economic desperation that sustains a ready supply of military labour. When all is said and done, it is for material needs that the tribute to the nation is offered. This is what the mother alludes to when she weighs in on the decision to send her son into military service. Her words echo those I heard from a mother of a soldier in Chakwal, “Money has no value, agar puttar nahio labda (if you can’t find your son). If he had not become a naukar (gone to serve in the military) he would not be a shaheed and would be alive today.” The BBC Urdu news report on the Galwan incident also mentions devastated Indian fathers, one in particular who has been in a state of shock and has not uttered a word since the dreaded phone call arrived announcing his son’s death. Like the stories in Pakistan, these are stories of grief that refuse to follow script; they flow along like tears, unhindered and unchecked, even as parallel scripts of pride and sacrifice remain intact.

In these villages, in Pakistan and in India, the suffering caused by military death shifts between the private and public realms. These are repertoires of grief obscured by the politics of sacrifice and drowned under more amplified appeals to nationalism. What may we learn if we were to not appropriate these stories, not throw slogans or jingoism at them and not filter loss through the colour of a uniform or flag. What may we learn if we paid attention to the muffled sound of wailing, mixing with yet distinct from the stories of pride and resolute sacrifice for the nation. And perhaps more fundamental, what may we learn if we recognized the sameness in suffering and commonalities of the experience of war across fiercely contested borders.

The writer is a feminist practitioner, trainer, and researcher associated with the field of gender, masculinities, and violence. Excerpts have been taken from the author’s book ‘Dying to Serve, Militarism, Affect and the Politics of Sacrifice in the Pakistan Army’ published by Stanford University Press in 2020