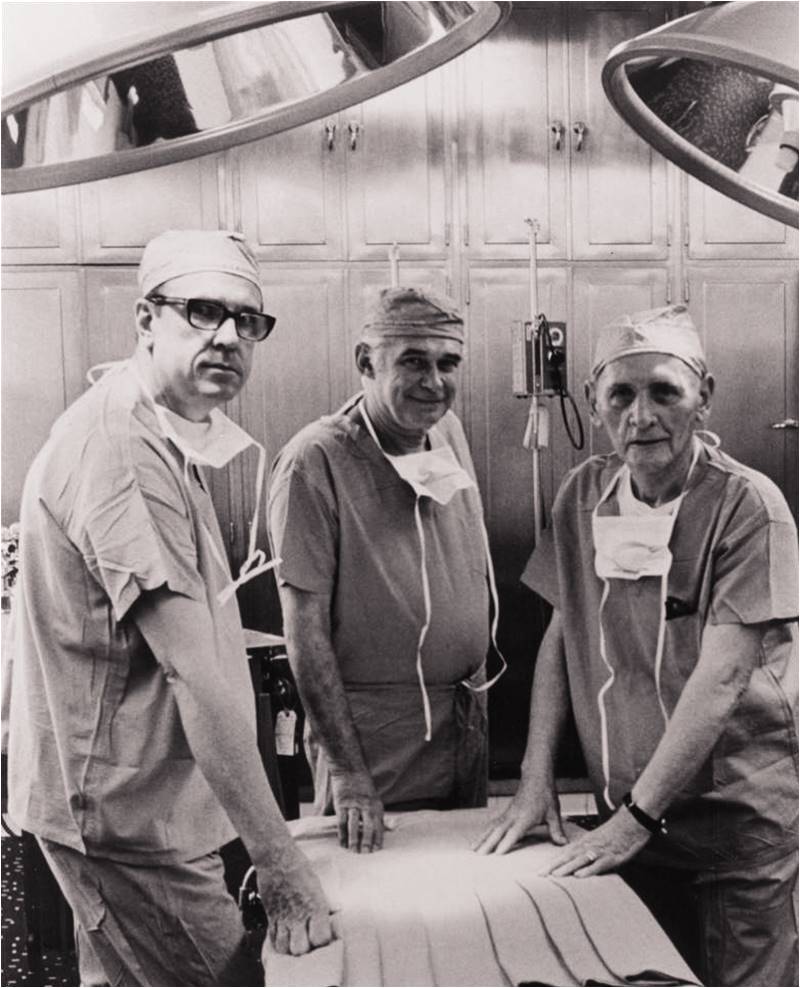

This photograph shows surgeons ahead of the first successful kidney transplant. On June 17, 1950, Richard Lawler performed this operation at Little Company of Mary Hospital. The patient was Ruth Tucker, a 49-year-old with polycystic kidney disease (PKD).

Both of Tucker’s kidneys had been affected, with one no longer functioning and the other functioning at only 10 percent. Tucker’s mother and sister had died from PKD, and a kidney transplant was her only option for survival because dialysis was not yet widely available.

After five weeks of waiting at the hospital for a suitable kidney, Tucker finally received one from a patient who had died of cirrhosis of the liver. This was an era that pre-dated tissue typing and immunosuppressive agents. Organ selection for transplants was based on simply finding someone of the same gender, blood type, and of roughly the same age and physical size.

In an interview after the surgery, Dr Lawler, who was the senior attending surgeon at Cook County Hospital and a faculty member at Stritch School of Medicine of Loyola University, commented: “Not the most ideal [donor] patient, but the best we could find.”

Dr Lawler had performed a few experimental organ transplants in dogs, and translated the knowledge he gained for performing the transplant in Tucker. He was assisted by James West, MD; Raymond Murphy, MD; Mary Lou Zidek, RN; and Nora O’Malley, a scrub nurse.

With roughly 40 other physicians looking on, Dr Lawler made quick work of the procedure. Within 45 minutes after removal of the donor kidney, the transplant was complete. Tucker was released from the hospital 30 days later.

Unfortunately, the new kidney was rejected by Tucker’s body and was removed 10 months after the initial surgery. But the transplant was not in vain. The new kidney did function for more than 60 days and helped restore normal kidney function in Tucker’s remaining kidney, allowing her to live for another five years. She died in 1955 from coronary artery disease not related to her PKD or to the organ transplant.

After Dr Lawler’s seminal procedure, other US and French physicians attempted kidney transplant procedures, but none of the patients survived. Again, immunosuppressive agents were not yet developed, and tissue typing was a thing of the future. Both would have greatly helped circumvent organ rejection.

The next successful transplant was done in 1954 by physicians at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, Boston, MA, on a set of identical twins when a kidney was donated by Ronald Herrick and transplanted to his brother Richard.

By the 1960s, immunosuppressive drugs and tissue typing were available, and organ transplants became less dangerous. Between 1954 and 1973, approximately 10,000 kidney transplants were performed.

In the 1980s, with the development of cyclosporine, transplant surgeries became more commonplace as well as more successful. In 1986, almost 9,000 kidney transplants were performed in the United States, with a one-year survival rate of 85 percent. Currently, almost 70,000 kidney transplants are performed worldwide each year.

Dr Lawler retired in 1979 and died in 1982. Unfortunately, he never performed another transplant, and he famously said that he “just wanted to get it started.”

Both of Tucker’s kidneys had been affected, with one no longer functioning and the other functioning at only 10 percent. Tucker’s mother and sister had died from PKD, and a kidney transplant was her only option for survival because dialysis was not yet widely available.

After five weeks of waiting at the hospital for a suitable kidney, Tucker finally received one from a patient who had died of cirrhosis of the liver. This was an era that pre-dated tissue typing and immunosuppressive agents. Organ selection for transplants was based on simply finding someone of the same gender, blood type, and of roughly the same age and physical size.

In an interview after the surgery, Dr Lawler, who was the senior attending surgeon at Cook County Hospital and a faculty member at Stritch School of Medicine of Loyola University, commented: “Not the most ideal [donor] patient, but the best we could find.”

Dr Lawler had performed a few experimental organ transplants in dogs, and translated the knowledge he gained for performing the transplant in Tucker. He was assisted by James West, MD; Raymond Murphy, MD; Mary Lou Zidek, RN; and Nora O’Malley, a scrub nurse.

With roughly 40 other physicians looking on, Dr Lawler made quick work of the procedure. Within 45 minutes after removal of the donor kidney, the transplant was complete. Tucker was released from the hospital 30 days later.

Unfortunately, the new kidney was rejected by Tucker’s body and was removed 10 months after the initial surgery. But the transplant was not in vain. The new kidney did function for more than 60 days and helped restore normal kidney function in Tucker’s remaining kidney, allowing her to live for another five years. She died in 1955 from coronary artery disease not related to her PKD or to the organ transplant.

After Dr Lawler’s seminal procedure, other US and French physicians attempted kidney transplant procedures, but none of the patients survived. Again, immunosuppressive agents were not yet developed, and tissue typing was a thing of the future. Both would have greatly helped circumvent organ rejection.

The next successful transplant was done in 1954 by physicians at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, Boston, MA, on a set of identical twins when a kidney was donated by Ronald Herrick and transplanted to his brother Richard.

By the 1960s, immunosuppressive drugs and tissue typing were available, and organ transplants became less dangerous. Between 1954 and 1973, approximately 10,000 kidney transplants were performed.

In the 1980s, with the development of cyclosporine, transplant surgeries became more commonplace as well as more successful. In 1986, almost 9,000 kidney transplants were performed in the United States, with a one-year survival rate of 85 percent. Currently, almost 70,000 kidney transplants are performed worldwide each year.

Dr Lawler retired in 1979 and died in 1982. Unfortunately, he never performed another transplant, and he famously said that he “just wanted to get it started.”