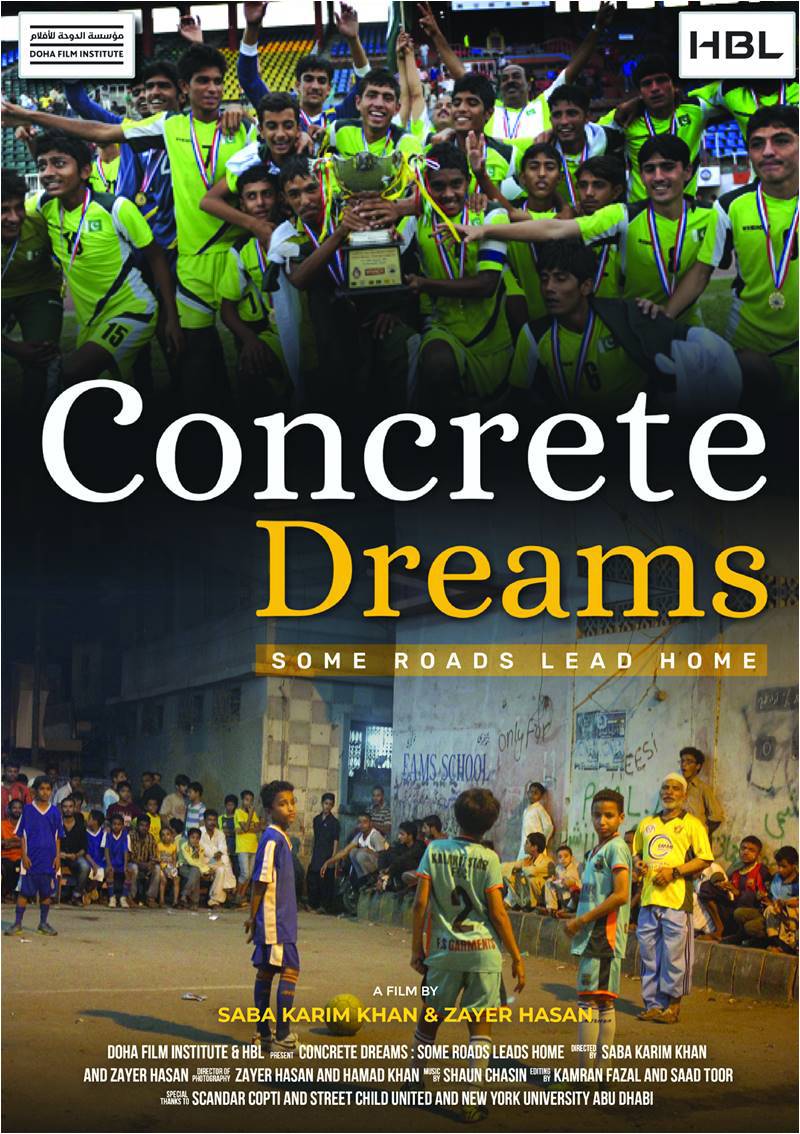

Concrete Dreams: Some Roads Lead Home is a documentary film directed by Saba Karim Khan and Zayer Hasan, officially selected at the Docs Without Borders Film Festival competition (DWBFF), the Indian World Film Festival, the Tagore International Film Festival (TIFF) and the Calcutta International Cult Film Festival. The film has also won best documentary awards at three international festivals. It follows the story of two young boys, Owais and Salman, who discover each other on the streets of Karachi, strike up an unpredictable friendship and become football champs, sparking the “I am Somebody” movement to impact the lives of 1.5 million children inhabiting Pakistan’s streets.

Sara Pan Algarra: Concrete Dreams is your first outing with visual storytelling! How did documentary filmmaking come about?

Saba Karim Khan: Well, the superficial answer has to be that the prospect of being a “doc-filmmaker” always felt crushingly prodigious!

But seriously, any form of creative storytelling produces excitement, even old-fashioned imaginings of sitting around a campfire telling tales fascinate me. I used to think (still do), that storytelling rarely runs the risk of becoming routinized; you can invent re-enchanting, distinctive, soul-stirring ways of telling stories each time and so, the novelty doesn’t fade. Too often, our jobs make us feel as if we’re cogs in a wheel, driven by the paycheck motive without experiencing happiness or fulfillment necessarily. Over time, that frustration calcifies but we find ourselves unable to get off the treadmill. I certainly did! At the back of my mind, that was a big problem and so, I was desperate to try and turn the ambition of telling a story into reality someday. I just wasn’t confident if, how and when it might materialize.

Concrete Dreams took root soon after I’d quit my Citibank job in Pakistan, to trail my husband in his new banking gig in Doha. I was petrified of being out of work for long and began frantically applying for jobs even before getting there. In that first week after arriving, I was toying with various possibilities – I suppose that happens when all you have is time on your hands – and I realized this might be that rare window to pursue something I’d been putting off because of my all-consuming corporate day-job.

Of course, I had no clue where to begin so I relied on good old Google. It was a long shot, but I’d read about independent filmmakers stumbling upon their first projects in accidental, unprobeable ways. Incidentally, I found out about DFI, got in touch and from thereon, took a chance with writing the script and treatment, pulling the grant application together and bidding the project full steam. It’s what our CEO at Citibank would say: “fail but never for lack of trying!” I think I took his advice really seriously! Fortunately, DFI green-lit the proposal and here we are with Concrete Dreams.

Sara Pan Algarra: At the heart of it, what is Concrete Dreams wanting to convey?

Saba Karim Khan: Courage. Resilience. Hope.

I’ve always struggled with how the attention economy has us in its grips by peddling catastrophic narratives about Pakistan with such terrifying regularity. It makes sense though, for fear gets much more traction than happy news. What it’s done, however, is produced an anxiety epidemic around us. We’re a perpetually harried nation, defensive, desperately trying to overthrow the “Poor Pakistan” story being fed the world over.

I wanted Concrete Dreams to bridle against playing to that victim gallery, to do something different. I’d been writing about street life before but with the doc-film, I wanted to layer on to this brutal reality, the flip side of the coin; that is to say, without flouting the problem of 1.5 million street children (the film does highlight the perilous life of Karachi’s streets – drugs, crime, mafias, sexual abuse), show how these aren’t completely unmoored, rootless, non-agentive street kids for whom its game over. They suffer, yes, but they are also talented, industrious dreamers, going from having no birth-certificates, never having entered an airport, to winning Bronze for Pakistan at the Street Child Football World Cup in Rio. There’s such gravitas to their character arcs, I wanted Concrete Dreams to capture that voluminous inner strength, to show it isn’t something necessarily confined to the territory of the “privileged”.

I was also very cautious about not turning this into a story about a one-time sports win and photo-op or about any organization and its agenda. It’s about real kids grappling with a central tension in their lives, an internal restlessness: of their divided selves, living in the avalanche-like gap between their dreams and realities. Then going on to spark a movement around football, forging new identities, to be able to say, “I am Somebody” and you better let me speak for myself. Above all, for others to look at them and say, “If he can do it, what’s stopping me?”

Sara Pan Algarra: What was the process of making Concrete Dreams like? Is it challenging being a Pakistani female documentary filmmaker?

Saba Karim Khan: Experimental, provocative, often doubtful, I’d say Concrete Dreams has been all those things. I have no training in filmmaking, just infinite amounts of gusto and somewhere along the way, you realize that zest can take you only so far. Filmmaking is, after all, a craft. So, I turned to some wonderful colleagues in filmmaking at NYU who were unstinting with their time and advice. I also had a really skilled co-director/ DoP on the project and a really inspiring music director. Their patience never outran, despite the frustrations posed by my being a first timer.

The part I relished most was speaking to the children and their families, not just Owais and Salman but so many others who’d played on the same Street Child World Cup football team. It opened up these magic portals into parts of Karachi – allegedly my hometown - which I’d never witnessed before. Of course, it sharpened the class divide too, but somehow felt raw and authentic. That’s a big reason why we’ve avoided prescriptive talking heads in the film and let the boys’ voices be ascendant.

I’m not naïve about the potential gendered trials in filmmaking (which are not even necessarily confined to Pakistan), but am perhaps too new to be fully cognizant of them yet. Maybe with my next – which might be seen as a more polemic subject in any case – I’ll be in a better position to answer this. Fortunately, with Concrete Dreams, I never got the sense of pushback because I’m a woman. On the contrary, the process of co-creation, despite having an all-male crew, felt refreshingly inclusive and comfortable.

Sara Pan Algarra: The role of sports in introducing social change, overcoming trauma, homelessness, domestic violence against children, among other very difficult problems that the world confronts is crucial. How do you see sports as mobilizing change and building better opportunities in Pakistan?

Saba Karim Khan: Incredibly crucial! Pakistan is ablaze with young sporting talent at the grassroots; it’s more a question of scouting them out of these gulleys and offering tangible platforms to nurture that talent. Amidst the chaotic lives that so many of these children lead – everyday strains of earning money, food, shelter etc. – the pursuit of sports can be seen as a luxury instead of a necessity. However, if done smartly, there are ways to turn their sporting prowess into an asset that can eventually address some of those burdens, as we’ve seen in Owais and Salman’s trajectories. What’s equally important is that initiatives don’t get diluted by corporate agendas and optics. This is not simply about a fancy, exotic press release to tick off a one-time CSR project with “poor, downtrodden” kids. This is way more consequential; it’s about touching the world and the individual lives that occupy it. The only way to keep our eyes on the actual prize is if we place the children at the center of the agenda. Change should hopefully follow from thereon.

Sara Pan Algarra: You wrapped up recently, but Concrete Dreams is already having a successful run at the international film festival circuit. In this short time, it’s won three awards and been officially selected at four international festivals. Is this how you’d hoped the film would be received?

Saba Karim Khan: Since I’ve never done this before, there’s immense much trial and error, so any festival selections and awards definitely offer validation. Frankly, I never imagined it would win a single award! All credit to my co-director/ DoP for insisting we submit to festivals.

But my real hope with Concrete Dreams is for it to have a certain resonance with anyone who watches it – at a festival, on mobile phones, in streets and alleyways – for people to see Owais and Salman’s story and think, this is the stuff that dreams are made of but guess what, it’s real! Then maybe reconsider their own positionality and lives, no matter where one is born, and reach for some of those dreams that we are taught to neatly fold and store away from such an early age. If people begin to think after watching the film, that won’t be a bad starting point.

Sara Pan Algarra: The Subcontinent has had a rich oral history and storytelling tradition. Have you seen this change over time, especially in light of the digital landscape?

Saba Karim Khan: There’s definitely a rich tapestry of storytelling in this part of the world and much to be preserved from it. We grew up with 8pm being standard family time, crouched around a stodgy television with faulty antennas, to collectively view Dhoop Kinare and Ankahi. Cut to 2020 and my 2.5-year-old is scrambling for an iPad! So, I really miss the vibe of hunkered down, communal storytelling with friends and family, laughing at the same jokes, rooting for the same protagonists, feigning stoicism during a heartbreaking scene!

The digital arena is democratizing the field a bit more, demolishing the ivory tower storytelling concept from yesteryears but it’s a double-edged sword, when one thinks about slippages with quality control. The balance between commerce and creativity is always fragile, near impossible to strike, so whilst more people entering the field is good news, we also don’t want to relegate our storytelling to a formulaic, cookie-cutter catastrophe.

Sara Pan Algarra: What are you working on next?

Saba Karim Khan: It’s at a very embryonic phase right now so I feel a bit jittery bringing it up. What I can say is it’s also a doc-film, a human story but with an even more delicate arc than Concrete Dreams, so I’m afraid it’ll get overwhelmed. It unpacks part of the prickly, knotty mess of #metoo in Pakistan, how it’s upended people’s lives across genders, which obviously requires immense sensitivity, restraint and a carefully considered perspective. Let’s hope it sees the light.

Sara Pan Algarra received acting training at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts. Her most recent theatre work on directing involves using toys to stage Samuel Beckett’s “All That Fall” renown radio play. She is the leader of “Where is our home?”, a children’s book project to contribute to early childhood literacy education of refugee children in Jordan

***

Sara Pan Algarra: Concrete Dreams is your first outing with visual storytelling! How did documentary filmmaking come about?

Saba Karim Khan: Well, the superficial answer has to be that the prospect of being a “doc-filmmaker” always felt crushingly prodigious!

But seriously, any form of creative storytelling produces excitement, even old-fashioned imaginings of sitting around a campfire telling tales fascinate me. I used to think (still do), that storytelling rarely runs the risk of becoming routinized; you can invent re-enchanting, distinctive, soul-stirring ways of telling stories each time and so, the novelty doesn’t fade. Too often, our jobs make us feel as if we’re cogs in a wheel, driven by the paycheck motive without experiencing happiness or fulfillment necessarily. Over time, that frustration calcifies but we find ourselves unable to get off the treadmill. I certainly did! At the back of my mind, that was a big problem and so, I was desperate to try and turn the ambition of telling a story into reality someday. I just wasn’t confident if, how and when it might materialize.

Concrete Dreams took root soon after I’d quit my Citibank job in Pakistan, to trail my husband in his new banking gig in Doha. I was petrified of being out of work for long and began frantically applying for jobs even before getting there. In that first week after arriving, I was toying with various possibilities – I suppose that happens when all you have is time on your hands – and I realized this might be that rare window to pursue something I’d been putting off because of my all-consuming corporate day-job.

Of course, I had no clue where to begin so I relied on good old Google. It was a long shot, but I’d read about independent filmmakers stumbling upon their first projects in accidental, unprobeable ways. Incidentally, I found out about DFI, got in touch and from thereon, took a chance with writing the script and treatment, pulling the grant application together and bidding the project full steam. It’s what our CEO at Citibank would say: “fail but never for lack of trying!” I think I took his advice really seriously! Fortunately, DFI green-lit the proposal and here we are with Concrete Dreams.

“It’s about real kids grappling with a central tension in their lives, an internal restlessness: of their divided selves, living in the avalanche-like gap between their dreams and realities”

Sara Pan Algarra: At the heart of it, what is Concrete Dreams wanting to convey?

Saba Karim Khan: Courage. Resilience. Hope.

I’ve always struggled with how the attention economy has us in its grips by peddling catastrophic narratives about Pakistan with such terrifying regularity. It makes sense though, for fear gets much more traction than happy news. What it’s done, however, is produced an anxiety epidemic around us. We’re a perpetually harried nation, defensive, desperately trying to overthrow the “Poor Pakistan” story being fed the world over.

I wanted Concrete Dreams to bridle against playing to that victim gallery, to do something different. I’d been writing about street life before but with the doc-film, I wanted to layer on to this brutal reality, the flip side of the coin; that is to say, without flouting the problem of 1.5 million street children (the film does highlight the perilous life of Karachi’s streets – drugs, crime, mafias, sexual abuse), show how these aren’t completely unmoored, rootless, non-agentive street kids for whom its game over. They suffer, yes, but they are also talented, industrious dreamers, going from having no birth-certificates, never having entered an airport, to winning Bronze for Pakistan at the Street Child Football World Cup in Rio. There’s such gravitas to their character arcs, I wanted Concrete Dreams to capture that voluminous inner strength, to show it isn’t something necessarily confined to the territory of the “privileged”.

I was also very cautious about not turning this into a story about a one-time sports win and photo-op or about any organization and its agenda. It’s about real kids grappling with a central tension in their lives, an internal restlessness: of their divided selves, living in the avalanche-like gap between their dreams and realities. Then going on to spark a movement around football, forging new identities, to be able to say, “I am Somebody” and you better let me speak for myself. Above all, for others to look at them and say, “If he can do it, what’s stopping me?”

Sara Pan Algarra: What was the process of making Concrete Dreams like? Is it challenging being a Pakistani female documentary filmmaker?

Saba Karim Khan: Experimental, provocative, often doubtful, I’d say Concrete Dreams has been all those things. I have no training in filmmaking, just infinite amounts of gusto and somewhere along the way, you realize that zest can take you only so far. Filmmaking is, after all, a craft. So, I turned to some wonderful colleagues in filmmaking at NYU who were unstinting with their time and advice. I also had a really skilled co-director/ DoP on the project and a really inspiring music director. Their patience never outran, despite the frustrations posed by my being a first timer.

The part I relished most was speaking to the children and their families, not just Owais and Salman but so many others who’d played on the same Street Child World Cup football team. It opened up these magic portals into parts of Karachi – allegedly my hometown - which I’d never witnessed before. Of course, it sharpened the class divide too, but somehow felt raw and authentic. That’s a big reason why we’ve avoided prescriptive talking heads in the film and let the boys’ voices be ascendant.

I’m not naïve about the potential gendered trials in filmmaking (which are not even necessarily confined to Pakistan), but am perhaps too new to be fully cognizant of them yet. Maybe with my next – which might be seen as a more polemic subject in any case – I’ll be in a better position to answer this. Fortunately, with Concrete Dreams, I never got the sense of pushback because I’m a woman. On the contrary, the process of co-creation, despite having an all-male crew, felt refreshingly inclusive and comfortable.

Sara Pan Algarra: The role of sports in introducing social change, overcoming trauma, homelessness, domestic violence against children, among other very difficult problems that the world confronts is crucial. How do you see sports as mobilizing change and building better opportunities in Pakistan?

Saba Karim Khan: Incredibly crucial! Pakistan is ablaze with young sporting talent at the grassroots; it’s more a question of scouting them out of these gulleys and offering tangible platforms to nurture that talent. Amidst the chaotic lives that so many of these children lead – everyday strains of earning money, food, shelter etc. – the pursuit of sports can be seen as a luxury instead of a necessity. However, if done smartly, there are ways to turn their sporting prowess into an asset that can eventually address some of those burdens, as we’ve seen in Owais and Salman’s trajectories. What’s equally important is that initiatives don’t get diluted by corporate agendas and optics. This is not simply about a fancy, exotic press release to tick off a one-time CSR project with “poor, downtrodden” kids. This is way more consequential; it’s about touching the world and the individual lives that occupy it. The only way to keep our eyes on the actual prize is if we place the children at the center of the agenda. Change should hopefully follow from thereon.

Sara Pan Algarra: You wrapped up recently, but Concrete Dreams is already having a successful run at the international film festival circuit. In this short time, it’s won three awards and been officially selected at four international festivals. Is this how you’d hoped the film would be received?

Saba Karim Khan: Since I’ve never done this before, there’s immense much trial and error, so any festival selections and awards definitely offer validation. Frankly, I never imagined it would win a single award! All credit to my co-director/ DoP for insisting we submit to festivals.

But my real hope with Concrete Dreams is for it to have a certain resonance with anyone who watches it – at a festival, on mobile phones, in streets and alleyways – for people to see Owais and Salman’s story and think, this is the stuff that dreams are made of but guess what, it’s real! Then maybe reconsider their own positionality and lives, no matter where one is born, and reach for some of those dreams that we are taught to neatly fold and store away from such an early age. If people begin to think after watching the film, that won’t be a bad starting point.

Sara Pan Algarra: The Subcontinent has had a rich oral history and storytelling tradition. Have you seen this change over time, especially in light of the digital landscape?

Saba Karim Khan: There’s definitely a rich tapestry of storytelling in this part of the world and much to be preserved from it. We grew up with 8pm being standard family time, crouched around a stodgy television with faulty antennas, to collectively view Dhoop Kinare and Ankahi. Cut to 2020 and my 2.5-year-old is scrambling for an iPad! So, I really miss the vibe of hunkered down, communal storytelling with friends and family, laughing at the same jokes, rooting for the same protagonists, feigning stoicism during a heartbreaking scene!

The digital arena is democratizing the field a bit more, demolishing the ivory tower storytelling concept from yesteryears but it’s a double-edged sword, when one thinks about slippages with quality control. The balance between commerce and creativity is always fragile, near impossible to strike, so whilst more people entering the field is good news, we also don’t want to relegate our storytelling to a formulaic, cookie-cutter catastrophe.

“The digital arena is democratizing the field a bit more, demolishing the ivory tower storytelling concept from yesteryears but it’s a double-edged sword, when one thinks about slippages with quality control”

Sara Pan Algarra: What are you working on next?

Saba Karim Khan: It’s at a very embryonic phase right now so I feel a bit jittery bringing it up. What I can say is it’s also a doc-film, a human story but with an even more delicate arc than Concrete Dreams, so I’m afraid it’ll get overwhelmed. It unpacks part of the prickly, knotty mess of #metoo in Pakistan, how it’s upended people’s lives across genders, which obviously requires immense sensitivity, restraint and a carefully considered perspective. Let’s hope it sees the light.

Sara Pan Algarra received acting training at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts. Her most recent theatre work on directing involves using toys to stage Samuel Beckett’s “All That Fall” renown radio play. She is the leader of “Where is our home?”, a children’s book project to contribute to early childhood literacy education of refugee children in Jordan