We are passing through uncertain times. While cases of coronavirus infection are on the rise, the government has announced a relaxation in the lockdown. It is stated that we have to learn to live with the virus. The marginalised segment of our society is already living with disease, poverty and injustice. Now, we need to think about how can we ‘open up’ our government after the lockdown ends? Whilst the lockdown hits the poor and vulnerable most, those sitting in comfortable zones should use this time to consider ways to expose our government and all of our policymakers, to a severe but cleansing light. COVID-19 has exposed gaps in our policymaking and institutional outlook. We need to reset our national priorities.

Our executive branch seems to have ‘hope’ and ‘faith’, but without due appreciation for ‘national unity’ or ‘discipline.’ Egos appear to supersede the pursuit of any national consensus—a need that is, paradoxically, exaggerated in normal times but, evidently, forgotten when it is most needed. Our political leaders seem to lack any appreciation for the reality we confront. Why have our elected leaders been unable to help us avoid widespread poverty and injustice? Why have our governments failed to provide health, education, and employment to the people? Why our institutions are not efficient enough and strong?

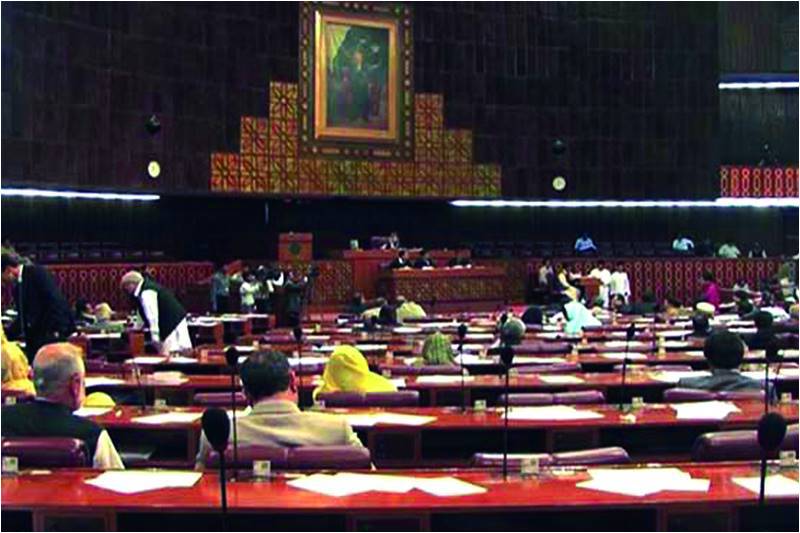

Even beyond the government, our legislature has lost its credibility, being unable to perform its primary role, namely law making through parliament. Unfortunately, frequent laws in our country are promulgated through an ordinance by the executive. There is hardly any meaningful debate in the parliament. Is a ‘democracy’ not a government of the people, by the people, and for its people? Is not ‘democracy’ without a functional parliament an oxymoron? Is it not the legislature’s responsibility to address the needs of our society through effective law making? Indeed, are our legislators accountable to their leader…or their voters? Clearly, a government with a functioning legislature acting for its people with appropriate laws is the need of the hour in Pakistan! In my opinion, our parliament should act for the people of Pakistan, not the vested interests of a particular leader or party; they should oppose any ordinance which is passed without ‘meaningful’ consultation: policy issues must be resolved through political forums.

One might also ask, with all due respect, a few questions of our judiciary. Has validating unconstitutional regimes made our country better? How can our judiciary demonstrate, through case-based decisions rather than suo motu policymaking, that judicial independence is a reality rather than a slogan in Pakistan? ‘Justice’ depends on clear and consistent judicial reasoning rooted in existing laws, not ‘popular’ decisions that simply reflect passing expressions of public opinion. The performance of judiciary is assessed based on the timely delivery and the quality of justice. Indeed, where our laws are inadequate, our parliament should be expected to improve them. Where financial support or independence is needed, the government should provide it.

And, finally, COVID-19 may help us update our understanding of national security to reflect a form of human security. The security of our people—surely the main point of any serious thinking about national security—requires an appreciation for the input of experts in health, economics, education, technology, politics, and law. Indeed, being located in a hostile neighbourhood, Pakistan needs adequate resources to safeguard state security. But it does not mean that public health and education are less important. We need to adopt a balanced approach to ensure both state security and human security. This twofold approach to security can guarantee our national security.

The current lockdown may it be smart or relaxed is, for those with the privilege of thinking rather than merely surviving, an opportunity. It is an opportunity to reconsider our approach to good governance, rooted in parliamentary power, the rule of law, and human security. This notion of good governance is one where all of our institutions perform their functions whilst remaining within the limits established by our constitution. Have different models of democracy (‘basic’, ‘Islamic’, ‘real’, and or ‘controlled’ democracy) helped us address the challenges we face? Has judicial activism promoted the rule of law, constitutionalism and the fundamental rights of the people? Has political disunity or lack of consensus amongst the federation and provinces or within political parties on issues of national importance strengthened our institutions? No.

Can I recommend, instead, a renewed pledge and focus on functional parliamentary democracy, national unity and discipline, and socio-economic justice aspired by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan? After the lockdown ends, this more than anything else will help our poor majority restore its confidence in the state. Beyond COVID-19, this will help us kill the enemies (marginalisation, injustice, and misallocations of power) eating the vitals of our nation from within.

The writer is an advocate in the Supreme Court of Pakistan

Our executive branch seems to have ‘hope’ and ‘faith’, but without due appreciation for ‘national unity’ or ‘discipline.’ Egos appear to supersede the pursuit of any national consensus—a need that is, paradoxically, exaggerated in normal times but, evidently, forgotten when it is most needed. Our political leaders seem to lack any appreciation for the reality we confront. Why have our elected leaders been unable to help us avoid widespread poverty and injustice? Why have our governments failed to provide health, education, and employment to the people? Why our institutions are not efficient enough and strong?

Even beyond the government, our legislature has lost its credibility, being unable to perform its primary role, namely law making through parliament. Unfortunately, frequent laws in our country are promulgated through an ordinance by the executive. There is hardly any meaningful debate in the parliament. Is a ‘democracy’ not a government of the people, by the people, and for its people? Is not ‘democracy’ without a functional parliament an oxymoron? Is it not the legislature’s responsibility to address the needs of our society through effective law making? Indeed, are our legislators accountable to their leader…or their voters? Clearly, a government with a functioning legislature acting for its people with appropriate laws is the need of the hour in Pakistan! In my opinion, our parliament should act for the people of Pakistan, not the vested interests of a particular leader or party; they should oppose any ordinance which is passed without ‘meaningful’ consultation: policy issues must be resolved through political forums.

We need to adopt a balanced approach to ensure both state security and human security

One might also ask, with all due respect, a few questions of our judiciary. Has validating unconstitutional regimes made our country better? How can our judiciary demonstrate, through case-based decisions rather than suo motu policymaking, that judicial independence is a reality rather than a slogan in Pakistan? ‘Justice’ depends on clear and consistent judicial reasoning rooted in existing laws, not ‘popular’ decisions that simply reflect passing expressions of public opinion. The performance of judiciary is assessed based on the timely delivery and the quality of justice. Indeed, where our laws are inadequate, our parliament should be expected to improve them. Where financial support or independence is needed, the government should provide it.

And, finally, COVID-19 may help us update our understanding of national security to reflect a form of human security. The security of our people—surely the main point of any serious thinking about national security—requires an appreciation for the input of experts in health, economics, education, technology, politics, and law. Indeed, being located in a hostile neighbourhood, Pakistan needs adequate resources to safeguard state security. But it does not mean that public health and education are less important. We need to adopt a balanced approach to ensure both state security and human security. This twofold approach to security can guarantee our national security.

The current lockdown may it be smart or relaxed is, for those with the privilege of thinking rather than merely surviving, an opportunity. It is an opportunity to reconsider our approach to good governance, rooted in parliamentary power, the rule of law, and human security. This notion of good governance is one where all of our institutions perform their functions whilst remaining within the limits established by our constitution. Have different models of democracy (‘basic’, ‘Islamic’, ‘real’, and or ‘controlled’ democracy) helped us address the challenges we face? Has judicial activism promoted the rule of law, constitutionalism and the fundamental rights of the people? Has political disunity or lack of consensus amongst the federation and provinces or within political parties on issues of national importance strengthened our institutions? No.

Can I recommend, instead, a renewed pledge and focus on functional parliamentary democracy, national unity and discipline, and socio-economic justice aspired by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan? After the lockdown ends, this more than anything else will help our poor majority restore its confidence in the state. Beyond COVID-19, this will help us kill the enemies (marginalisation, injustice, and misallocations of power) eating the vitals of our nation from within.

The writer is an advocate in the Supreme Court of Pakistan