The subject of law deals with social realities; it applies in a context; interpreted and understood in a specific situation. Criminal law regulates human conduct by defining offences and prescribing its punishment. Lawmakers promulgate new laws with a careful appreciation of social realities. Those who enforce the law must reasonably understand the law and rules they are called upon to enforce. Flawed legislation or its arbitrary enforcement limits the rights and liberties of the people.

The government of the Punjab has recently promulgated the Punjab Infectious Diseases (Prevention and Control) Ordinance 2020 for prevention and control of infectious diseases. Handling an epidemic with a legislative instrument is a necessary and appreciable step. However, such legislation must meet two requirements: first, it should strike a balance between the right to livelihood and the right to protection of the health of the people; second, it should ensure that fundamental rights of the people are not undermined seriously. The ordinance fails to meet both the requirements.

First, the ordinance ignores our social realities such as poverty and unemployment. Under Section 5 of the ordinance, a person may be required to abstain from working or trade and his right to movement can also be restricted. In other words, the poverty-stricken persons can be compelled to stay home - without adequate financial support by the government. The government’s initiative to help the poor through the Ehsaas Emergency Cash Programme promises a nominal amount that hardily meets the needs of any family. Whereas, a person can be detained through coercive measures which may lead to a conviction up to three months and a fine up to Rs50,000. Upon repeated violation, with imprisonment for a term up to one year (up to 18 months for running away from the place of detention) or a fine up to Rs100,000, or both (in case of a body corporate a fine up to Rs300,000). These stringent penalties, absent adequate financial security, may frustrate the poor and unemployed people and create anomalous behavior in the society.

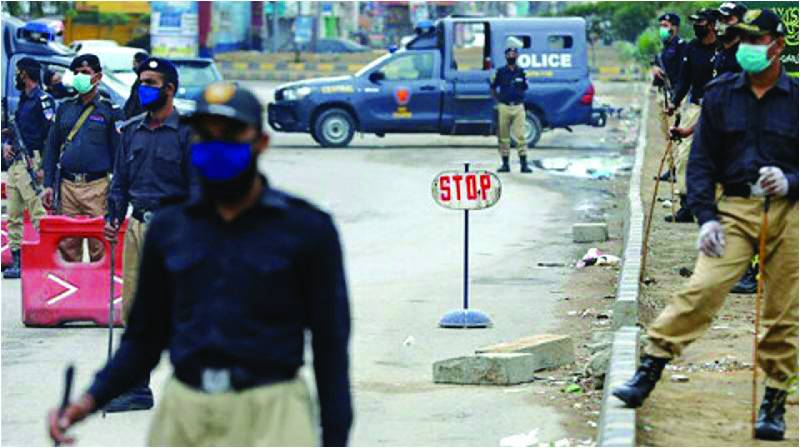

Second, the ordinance empowers the government to require doctors and government servants to perform their duties without providing protective equipment. Section 4 of the Ordinance envisages the imposition of a duty upon all registered medical practitioners and health facilities to treat cases of infection or contamination. Section 5 requires government servants such as police officials to monitor and control public health risk with a simple precaution that a person may be required to wear specified protective clothing. The violation of these obligations attracts above-mentioned punishment. The strict performance of these obligations, without the provision of essential personal protection equipment, may expose doctors and police to serious health risk.

Section 14 of the ordinance obliges every person to inform to a notified medical officer as to the infectious disease of any person under one’s care, supervision or control. Considering uncertain symptoms of the epidemic it may not be necessarily possible for a non-medical person to ascertain the symptoms and report the occurrence of disease to the relevant officer.

The ordinance imposes excessive obligations upon the people, the police officers and the doctors without the provision of adequate financial assistance and personal protection equipment. It provides unreasonable punishments. The conduct of the people can be regulated and improved combining minor penalties with awareness and educational tools.

The ordinance seems unnecessary when federal laws such as the Pakistan Penal Code, 1860 (PPC), and the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1898 (CrPC), already provide effective substantive law and procedural mechanism to handle human conduct in an emergency. Section 269 of the PPC provides a penalty up to six months or fine or both for a negligent act likely to spread the infection of any disease. Section 144 of the CrPC empowers district administration to issue orders in the public interest that may place a ban on an activity for a specific period of time. So, specifying or enhancing fine through ordinance, when people are suffering from economic constraints does not provide a good gesture and solution.

The ordinance seriously affects the right to life and liberty of the people that are protected under our constitution. Section 26 of the ordinance bars any civil or criminal remedies before any court of law against the action taken by government servants such. There is no denial of the proposition that restrictions can be imposed on fundamental rights in times of crisis and to protect public health. But it has to be done under a valid law. In any case, the content of the law which governs the life or liberty of the people must meet the requirements of the constitution. The ordinance fails to meet this requirement as it fails to ensure the means of subsistence (right to life) and protection from misuse of the state powers (right to dignity of man).

The ordinance further undermines the rights of the people while conferring extensive powers on police without proper training. When the content and scope of any law is imprecise the risk of its abuse is undeniable. In principle, the authority of government servants is not unlimited. They must know the limits provided under the constitution—ignorance of what a person is supposed to know is not an excuse. If a public officer disregards or ignores such limits he commits a fault, which cannot be protected under the bar provided in the ordinance.

Briefly, the ordinance should be substantively revised to provide enhanced measures for the protection of fundamental rights of the people. Besides, if so required, the federal legislature should promulgate a federal law aiming to combat the pandemic in the country in a coordinated and effective manner. It should make the obligations of public officers such as police and doctors clear and realistic. It should define a ‘negligent act’ with precision and distinguish between a ‘safety precautio’’ and a ‘legal obligation’ facilitating the government servants in the execution of the law. In short, federal law must protect both the right to livelihood and the right to protection of individual and public health in a balanced manner.

The writer is an advocate in the Supreme Court of Pakistan

The government of the Punjab has recently promulgated the Punjab Infectious Diseases (Prevention and Control) Ordinance 2020 for prevention and control of infectious diseases. Handling an epidemic with a legislative instrument is a necessary and appreciable step. However, such legislation must meet two requirements: first, it should strike a balance between the right to livelihood and the right to protection of the health of the people; second, it should ensure that fundamental rights of the people are not undermined seriously. The ordinance fails to meet both the requirements.

First, the ordinance ignores our social realities such as poverty and unemployment. Under Section 5 of the ordinance, a person may be required to abstain from working or trade and his right to movement can also be restricted. In other words, the poverty-stricken persons can be compelled to stay home - without adequate financial support by the government. The government’s initiative to help the poor through the Ehsaas Emergency Cash Programme promises a nominal amount that hardily meets the needs of any family. Whereas, a person can be detained through coercive measures which may lead to a conviction up to three months and a fine up to Rs50,000. Upon repeated violation, with imprisonment for a term up to one year (up to 18 months for running away from the place of detention) or a fine up to Rs100,000, or both (in case of a body corporate a fine up to Rs300,000). These stringent penalties, absent adequate financial security, may frustrate the poor and unemployed people and create anomalous behavior in the society.

The ordinance should be substantively revised to provide enhanced measures for the protection of fundamental rights of the people

Second, the ordinance empowers the government to require doctors and government servants to perform their duties without providing protective equipment. Section 4 of the Ordinance envisages the imposition of a duty upon all registered medical practitioners and health facilities to treat cases of infection or contamination. Section 5 requires government servants such as police officials to monitor and control public health risk with a simple precaution that a person may be required to wear specified protective clothing. The violation of these obligations attracts above-mentioned punishment. The strict performance of these obligations, without the provision of essential personal protection equipment, may expose doctors and police to serious health risk.

Section 14 of the ordinance obliges every person to inform to a notified medical officer as to the infectious disease of any person under one’s care, supervision or control. Considering uncertain symptoms of the epidemic it may not be necessarily possible for a non-medical person to ascertain the symptoms and report the occurrence of disease to the relevant officer.

The ordinance imposes excessive obligations upon the people, the police officers and the doctors without the provision of adequate financial assistance and personal protection equipment. It provides unreasonable punishments. The conduct of the people can be regulated and improved combining minor penalties with awareness and educational tools.

The ordinance seems unnecessary when federal laws such as the Pakistan Penal Code, 1860 (PPC), and the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1898 (CrPC), already provide effective substantive law and procedural mechanism to handle human conduct in an emergency. Section 269 of the PPC provides a penalty up to six months or fine or both for a negligent act likely to spread the infection of any disease. Section 144 of the CrPC empowers district administration to issue orders in the public interest that may place a ban on an activity for a specific period of time. So, specifying or enhancing fine through ordinance, when people are suffering from economic constraints does not provide a good gesture and solution.

The ordinance seriously affects the right to life and liberty of the people that are protected under our constitution. Section 26 of the ordinance bars any civil or criminal remedies before any court of law against the action taken by government servants such. There is no denial of the proposition that restrictions can be imposed on fundamental rights in times of crisis and to protect public health. But it has to be done under a valid law. In any case, the content of the law which governs the life or liberty of the people must meet the requirements of the constitution. The ordinance fails to meet this requirement as it fails to ensure the means of subsistence (right to life) and protection from misuse of the state powers (right to dignity of man).

The ordinance further undermines the rights of the people while conferring extensive powers on police without proper training. When the content and scope of any law is imprecise the risk of its abuse is undeniable. In principle, the authority of government servants is not unlimited. They must know the limits provided under the constitution—ignorance of what a person is supposed to know is not an excuse. If a public officer disregards or ignores such limits he commits a fault, which cannot be protected under the bar provided in the ordinance.

Briefly, the ordinance should be substantively revised to provide enhanced measures for the protection of fundamental rights of the people. Besides, if so required, the federal legislature should promulgate a federal law aiming to combat the pandemic in the country in a coordinated and effective manner. It should make the obligations of public officers such as police and doctors clear and realistic. It should define a ‘negligent act’ with precision and distinguish between a ‘safety precautio’’ and a ‘legal obligation’ facilitating the government servants in the execution of the law. In short, federal law must protect both the right to livelihood and the right to protection of individual and public health in a balanced manner.

The writer is an advocate in the Supreme Court of Pakistan