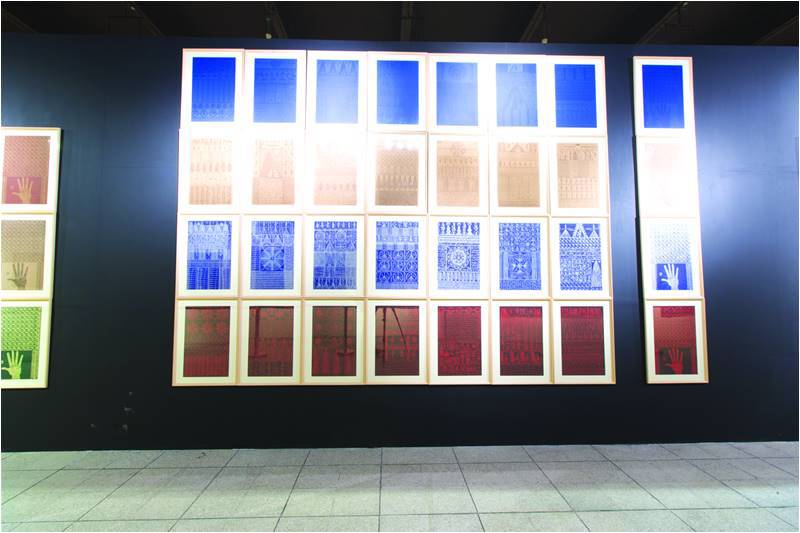

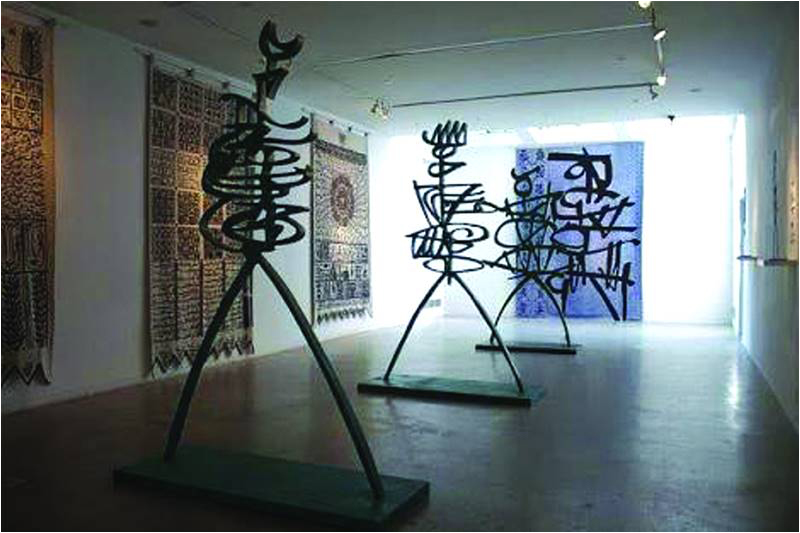

The truest statement I can make about Rachid Koraichi is that he is a most humane man. His beautiful work is a testament to the complex, philosophical yet essentially simple nature of the man himself. Redolent of humankind’s shared history of symbols, religions, love and death – all that passes between the heavens and the earth – Koraichi presents us with a dreamer’s gardens, inscribed ceramic bowls, carved stonework, cobalt blue etchings and richly embroidered textiles. For Rachid Koraichi, John Donne’s line “Every man’s death diminishes me”is a fitting description.

Laila Rahman (LR): At which stage in your working practice did “Tassawuf” (introspection and spiritual closeness to God) take on importance?

Rachid Koraichi (RK): The question is very good. It is important to know that my family comes from a religious family, from the same place as the Holy Prophet (PBUH), it is, [in fact], the same family [the Quraish] in Makkah. I was born in this already religious atmosphere - into a Sufi family. The milieau was Sufi - the Sheikh Ahmed al-Tijani Brotherhood, which is the main school of Sufi thought. My ancestor was Sheikh Ahmad al-Tijani, founder of the Tijaniyyah Sufi Order. He taught at the Al-Azhar Mosque in Cairo and the Al-Zaytuna [the Olive] Mosque in Tunisia. He was buried in Sidi Ahmed al-Tijani Zawiya complex in Fez, Morocco. I was born in Ain Beida, Algeria. The wars here have been very violent. During my childhood, there was war, bombings, etc, a terrible colonial hell between 1954-1962. Fortunately there was Sufism for me, also there was the presence of the Resistance against the colonial rulers.

[Rachid Korachi’s interpretation of Sufism may be seen, in his project “Jardins du Paradis” in the Chateau de Chaumont in the Loire region, France. Inspired by the Sufi works of Fariddudin Attar like “The Conference of the Birds”, the quest pursued over seven valleys to find the fabled bird, Simorgh; Koraichi interprets and references this symbolic journey by creating ceramic bowls in which rain-water collects. The placement of small bowls at the base of the tombstones on graves in the Muslim North African tradition, is for birds to drink from, so they may continue to traverse between the Earth and the sky. This is a symbolic journey, mirroring the eternal cycle of life and death.]

LR: In your work, why is all the text and lettering inverse?

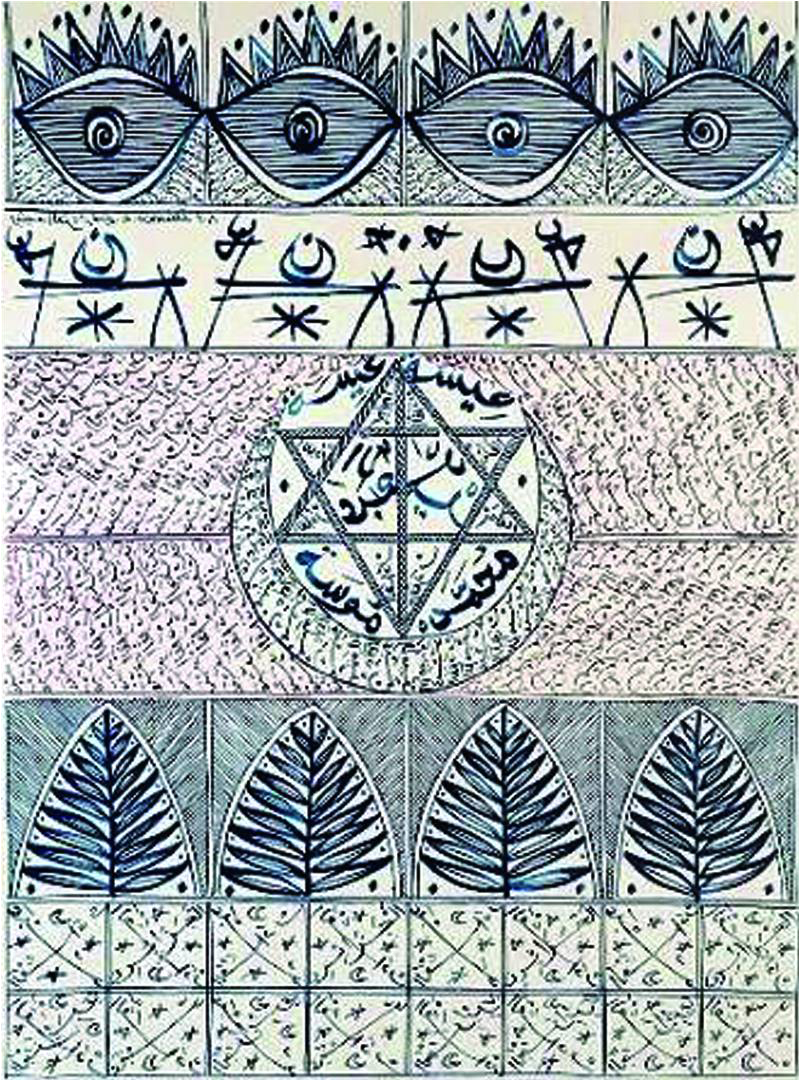

RK: I never take text from the Hadith or Quran, always from mystical Sufi texts, like Hallaj, Attar, Ibne Rumi, Ibne Arabi. They were not poets in the Western sense…more mystic philosophers. For me the inversion is to give a key [to my work], it’s not a gimmick. The term mysticism comes from mystery…we enter within [ourselves] to understand. The first time we look into a mirror, you see yourself…all your life you see yourself [in the mirror]. You don’t see reality, because the image is inverse. This inversion makes you think you’re looking at reality but you’re not. So, I would never see myself as you see me. I see you in your real reality, but you cannot see yourself.

God has made you in His image. For me, as a visual artist, [I want that] people from other countries should be able to see the work through their own eyes, looking and understanding…so the text is fragmented [in my work] and it follows the contours of the drawing. The work calls to your sentiments, sensations, culture, traumas, happiness…everyone who comes in front of the work, comes into contact with their past, their personal story, so the key I have, [to understanding our own selves and our souls], is not yours, it is mine. The form of the Arabic language has a very beautiful aesthetic, that allows you to do all sorts of things with it…reduce it, enlarge it.

On the walls of mosques, you see often written [the words] Hawa, God, Yahwe – written straight or written in reverse. To illustrate this point: in the old Medina section of Cairo, artisans are sitting on the ground, on carpets and cushions. A person passes by, [sees artisans working on hangings shamiyanas, using text in inverse, embroidering the designs for Rachid Korachi] and says to them, [the artisans], “you know this is not permitted by religion, you are working with the imagination and with the devil, you are doing everything opposite”. Therefore the artisans stopped working. So, the owner of the atelier [in Cairo, where RK works] called me and said the artisans had stopped work. So, I say, “Fine, I’ll come to Cairo. So I go there and visit the Al-Azhar mosque to pray there. The Imam shows me, in front of the mehrab/mimbar, some text written in reverse form. The Imam adds that they have never paid any attention to it. This story of the inversion can also be like the shadow of a person.

LR: So, would you say a shadow is real?

RK: The moment we are born and later start walking, there’s your shadow. Your shadow is like a digital imprint – it is with you all your life. When you die, your shadow enters your tomb [grave] with you. So, it is part of you…

[LR: This recalls to mind Plato’s Cave of Shadows, where the inhabitants of the cave knew only their closed world of the cave and believed their shadows to be real people and the cave to be the extent of their world.]

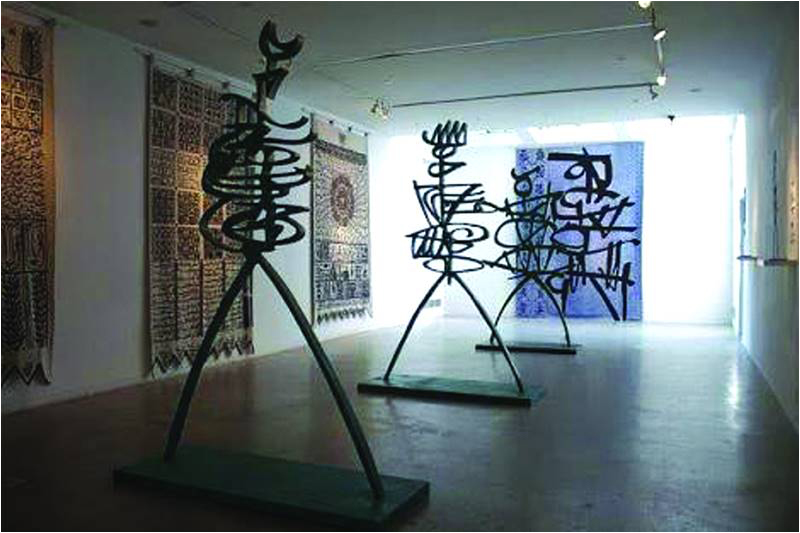

LR: What does the graphic element of calligraphy bring to your work, the sculptures, prints and ceramics?

RK: It is not calligraphy, it is writing. I would say it is the core of my work. I invent the symbols and it is my own writing.

LR: And the importance of the number seven for you?

RK: Judaism has seven Pillars of Wisdom, Christianity has Seven Cardinal Sins, in Islam, the Kalima is [comprised of] seven words, we perform seven Tawaafs (circles) around the Ka’aba, we stone the Shai’tan seven times, there are seven Hells and seven Heavens. The square shape signifying Earth and the pyramid, [seen from one side], make up four and three sides, [respectively] totaling the number seven. When we pray, we are using seven parts of our bodies, two feet, two knees, two hands and one head.

LR: How do you view mortality?

RK: Eternity is the absence of time. Bach, Beethoven, Maria Callas, Pavarotti – all are dead, but they are alive in their work [which remains with us]. The Earth is fertile, there are millions of dead bodies buried in it, they have made it fertile. It is the cycle of life: your body is going to nourish your grandchildren. We have never had a man return from Paradise.

The idea of God is magnificent: you are here because God made you, you wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t like that. The Earth belongs to God. We’re all going to depart. We will leave with no possessions. The explanation of spirituality is: it is less concrete than the Earth and the cycles of life. These are intellectual gymnastics…you can or cannot believe…I can smell someone or I cannot smell someone, it is like a blind person, it’s not that he can’t see, he sees things differently. If people had a little love, honesty and respect for others, humanity would be at peace.

LR: Please tell me about your grandfather and how he impacted your work?

RK: My grandfather said, “Everything that is not given is lost” [not passed on, not given in a spirit of humanity and generosity]. My response to this [statement] is the cemetery (graveyard). For people I don’t know, for their families…it’s what you call “giving”. Even a smile is giving something to someone.

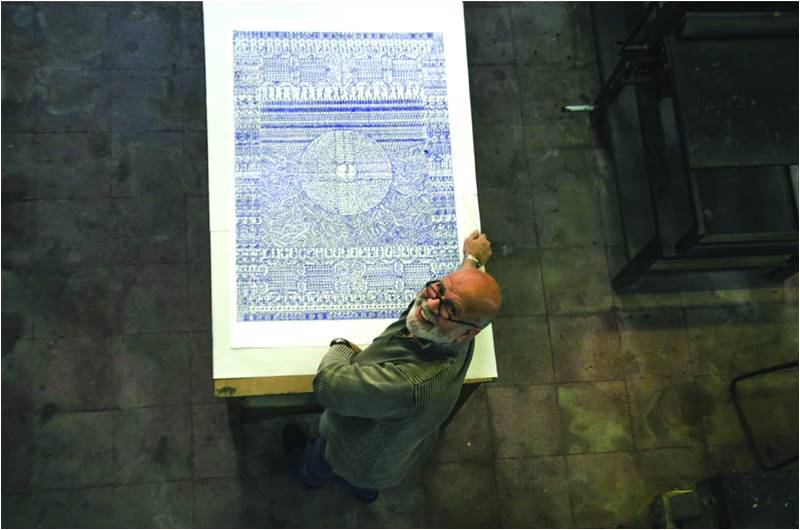

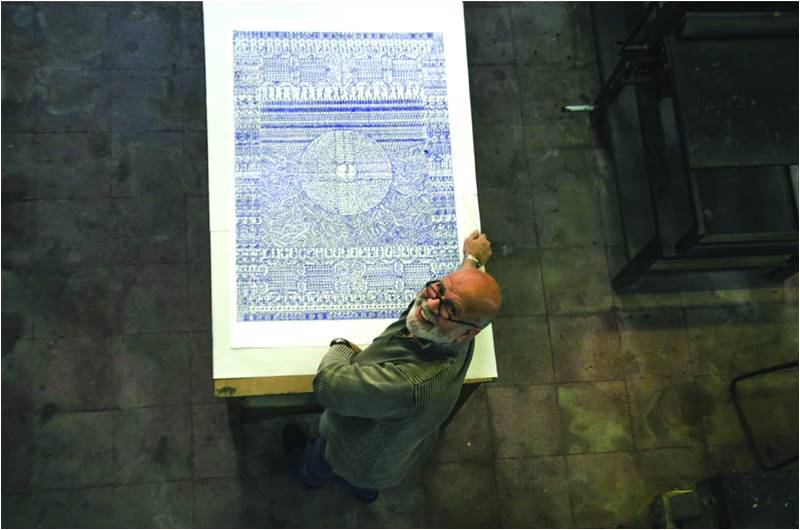

[LR: The cemetery referred to above, “Jardin d’Afrique” (Garden of Africa), is a large tract of land that Rachid Koraichi has purchased recently in southern Tunisia. The disregarded, immigrant dead washing up from the waters of the Mediterranean Sea remain unclaimed and unidentified. Koraichi has undertaken the humanitarian task of identifying and burying these nameless people. He proposes to establish a DNA lab at the site, so that the bodies to be buried here may first be identified. He then proposes to trace and inform their families. Irrespective of religion, caste or creed the people that will be buried here, will face Makkah, amidst lush gardens of jasmine, date and bougainvillea in the city of Zarzis. Keeping the “Jardin d’Afrique” cemetery (Garden of Africa) in mind, the etching Koraichi has recently made, printed at the Cowasjee Print Studio, NCA; is also titled “Jardin d’Afrique”. With its profusion of symbols; of waves, figures, trees, stars, using the geometric shapes of the circle and the square, the image is both complex and visually stunning.]

LR: What is the relevance of the primal elements of in your work?

RK: Fire turns clay into ceramic…iron, bronze [in sculptures], stone…water shapes the stones, [also used for cutting it]. It is the connectivity to family and continuity, for me. My book, “Water is too far for Fire which is Too Near”,…original text plus prints…there are forty nine original prints in the book, the mystic number seven multiplied by seven is forty nine. And the book is an edition of fifty. The original text is in French. It has also been translated into Spanish.

LR: Working on the textile pieces, there appear to be references to wars.

RK: Not wars, no. These are references to ancestors and eternity. I have done these for my ancestors, as a tribute. Like flags are distinctive symbols, to connect, to identify [clans, tribes] from the Holy Prophet’s (PBUH) time. Flags announced the arrival of the Holy Prophet (PBUH) when he traveled, for instance.

Like scarification, tattoos are distinctive symbols which we understand and read, to connect and identify with people from different tribes, to differentiate from one to another – not a separation but to distinguish. A symbol to identify within themselves as well…the differences of cultures, not against each other. In this way we have the passage from childhood to adulthood to old age, just to distinguish, not separate.

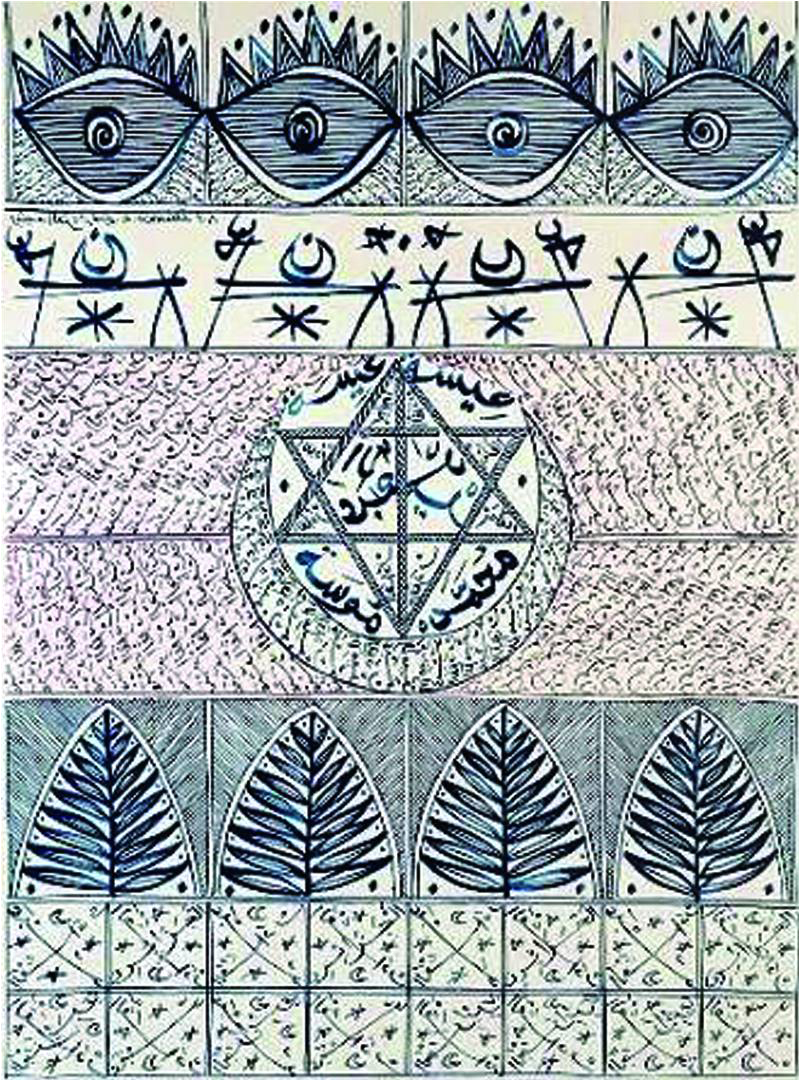

[LR: In the textiles displayed in the Lahore Museum, there are symbols of the hand (the alam), eyes, stars, date palms, rivers or seas, women, men, crescents; appliqued and stitched in rich silk and gold embroidery, as a tribute to the three revealed religions, with the intention of highlighting the many similarities between the three.]

LR: Do you see your own art practice as something that is a unifying force between East and West?

RK: It is a big pretension to claim that. The idea…like a spark…there’s always a context. Referring to the dead Algerians of the Resistance 1830s, buried in a mass grave at the Chateau d’Amboise, I made the “Jardin d’Orient”. The catalyst for this was that I was praying there one day. A woman’s pet dog came near me and peed near my feet. “Who are you?” she asked me. I said that I was Rachid Koraichi. She said, “Are you working here? My dog has the habit of peeing here since a long time.” My response was, “At least you’re sincere and honest in telling me this!”

This moment led to my thinking of making the cemetery [Jardin d’Orient”]. So, the dog was the catalyst. It was also “maktoob” - destiny, fate. Choices we make and don’t make…like being at a crossroads.

[The “Jardin d’Orient” created by Rachid Koraichi is a cemetery in tribute to the martyrs who were buried in a mass grave here; of the 1880s war, between Algeria and Syria. This lies in the gardens of the Chateau d’Amboise in France, one of the palaces of Francois I, of France. It is comprised of blocks of stone with carving near their top rims, referencing the Ka’aba. A construction of a metal form, a medallion of text and symbols, tops these blocks, but this form is only easily readable when it casts its’ shadow onto the surface of the block. A line of seven cypress trees edges this harmonious space. A diagonal line of sage bushes, cuts through the grave blocks, which points in the direction of Makkah. Nearby the tomb of Leonardo da Vinci stands as a witness to this space.]

LR: Where do you situate yourself vis-a-vis individuality?

RK: My family lived in the desert, before Sufism, where you can’t live alone. Any family has to live in a community. I am currently living in my family home, in the desert. In the world there are 300 million Tijanis. I live in the company of Sufis. Someone who tells you “I am a Sufi” is not a Sufi.

***

Rachid Koraichi enriched the hearts and minds of all whom he came into contact with during the Lahore Biennale 02, this year. The stories he weaves in his work – whether it is a ceramic bowl or a bronze sculpture of a man, made up of intricate swirls of Arabic text, be it a play on the shadow or symbols adorning a huge tapestry – show that all his work is imbued with philosophical purpose, complexity and strength.

With grateful thanks to Nadia Khawaja for translating the French and Prof. Naazish Ata-Ullah, in whose living room the interview was conducted. All imperfections in translation are mine alone.

Laila Rahman is an artist and teaches at the National College of Arts, Lahore

***

Laila Rahman (LR): At which stage in your working practice did “Tassawuf” (introspection and spiritual closeness to God) take on importance?

Rachid Koraichi (RK): The question is very good. It is important to know that my family comes from a religious family, from the same place as the Holy Prophet (PBUH), it is, [in fact], the same family [the Quraish] in Makkah. I was born in this already religious atmosphere - into a Sufi family. The milieau was Sufi - the Sheikh Ahmed al-Tijani Brotherhood, which is the main school of Sufi thought. My ancestor was Sheikh Ahmad al-Tijani, founder of the Tijaniyyah Sufi Order. He taught at the Al-Azhar Mosque in Cairo and the Al-Zaytuna [the Olive] Mosque in Tunisia. He was buried in Sidi Ahmed al-Tijani Zawiya complex in Fez, Morocco. I was born in Ain Beida, Algeria. The wars here have been very violent. During my childhood, there was war, bombings, etc, a terrible colonial hell between 1954-1962. Fortunately there was Sufism for me, also there was the presence of the Resistance against the colonial rulers.

[Rachid Korachi’s interpretation of Sufism may be seen, in his project “Jardins du Paradis” in the Chateau de Chaumont in the Loire region, France. Inspired by the Sufi works of Fariddudin Attar like “The Conference of the Birds”, the quest pursued over seven valleys to find the fabled bird, Simorgh; Koraichi interprets and references this symbolic journey by creating ceramic bowls in which rain-water collects. The placement of small bowls at the base of the tombstones on graves in the Muslim North African tradition, is for birds to drink from, so they may continue to traverse between the Earth and the sky. This is a symbolic journey, mirroring the eternal cycle of life and death.]

LR: In your work, why is all the text and lettering inverse?

RK: I never take text from the Hadith or Quran, always from mystical Sufi texts, like Hallaj, Attar, Ibne Rumi, Ibne Arabi. They were not poets in the Western sense…more mystic philosophers. For me the inversion is to give a key [to my work], it’s not a gimmick. The term mysticism comes from mystery…we enter within [ourselves] to understand. The first time we look into a mirror, you see yourself…all your life you see yourself [in the mirror]. You don’t see reality, because the image is inverse. This inversion makes you think you’re looking at reality but you’re not. So, I would never see myself as you see me. I see you in your real reality, but you cannot see yourself.

God has made you in His image. For me, as a visual artist, [I want that] people from other countries should be able to see the work through their own eyes, looking and understanding…so the text is fragmented [in my work] and it follows the contours of the drawing. The work calls to your sentiments, sensations, culture, traumas, happiness…everyone who comes in front of the work, comes into contact with their past, their personal story, so the key I have, [to understanding our own selves and our souls], is not yours, it is mine. The form of the Arabic language has a very beautiful aesthetic, that allows you to do all sorts of things with it…reduce it, enlarge it.

On the walls of mosques, you see often written [the words] Hawa, God, Yahwe – written straight or written in reverse. To illustrate this point: in the old Medina section of Cairo, artisans are sitting on the ground, on carpets and cushions. A person passes by, [sees artisans working on hangings shamiyanas, using text in inverse, embroidering the designs for Rachid Korachi] and says to them, [the artisans], “you know this is not permitted by religion, you are working with the imagination and with the devil, you are doing everything opposite”. Therefore the artisans stopped working. So, the owner of the atelier [in Cairo, where RK works] called me and said the artisans had stopped work. So, I say, “Fine, I’ll come to Cairo. So I go there and visit the Al-Azhar mosque to pray there. The Imam shows me, in front of the mehrab/mimbar, some text written in reverse form. The Imam adds that they have never paid any attention to it. This story of the inversion can also be like the shadow of a person.

LR: So, would you say a shadow is real?

RK: The moment we are born and later start walking, there’s your shadow. Your shadow is like a digital imprint – it is with you all your life. When you die, your shadow enters your tomb [grave] with you. So, it is part of you…

[LR: This recalls to mind Plato’s Cave of Shadows, where the inhabitants of the cave knew only their closed world of the cave and believed their shadows to be real people and the cave to be the extent of their world.]

LR: What does the graphic element of calligraphy bring to your work, the sculptures, prints and ceramics?

RK: It is not calligraphy, it is writing. I would say it is the core of my work. I invent the symbols and it is my own writing.

LR: And the importance of the number seven for you?

RK: Judaism has seven Pillars of Wisdom, Christianity has Seven Cardinal Sins, in Islam, the Kalima is [comprised of] seven words, we perform seven Tawaafs (circles) around the Ka’aba, we stone the Shai’tan seven times, there are seven Hells and seven Heavens. The square shape signifying Earth and the pyramid, [seen from one side], make up four and three sides, [respectively] totaling the number seven. When we pray, we are using seven parts of our bodies, two feet, two knees, two hands and one head.

LR: How do you view mortality?

RK: Eternity is the absence of time. Bach, Beethoven, Maria Callas, Pavarotti – all are dead, but they are alive in their work [which remains with us]. The Earth is fertile, there are millions of dead bodies buried in it, they have made it fertile. It is the cycle of life: your body is going to nourish your grandchildren. We have never had a man return from Paradise.

The idea of God is magnificent: you are here because God made you, you wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t like that. The Earth belongs to God. We’re all going to depart. We will leave with no possessions. The explanation of spirituality is: it is less concrete than the Earth and the cycles of life. These are intellectual gymnastics…you can or cannot believe…I can smell someone or I cannot smell someone, it is like a blind person, it’s not that he can’t see, he sees things differently. If people had a little love, honesty and respect for others, humanity would be at peace.

LR: Please tell me about your grandfather and how he impacted your work?

RK: My grandfather said, “Everything that is not given is lost” [not passed on, not given in a spirit of humanity and generosity]. My response to this [statement] is the cemetery (graveyard). For people I don’t know, for their families…it’s what you call “giving”. Even a smile is giving something to someone.

[LR: The cemetery referred to above, “Jardin d’Afrique” (Garden of Africa), is a large tract of land that Rachid Koraichi has purchased recently in southern Tunisia. The disregarded, immigrant dead washing up from the waters of the Mediterranean Sea remain unclaimed and unidentified. Koraichi has undertaken the humanitarian task of identifying and burying these nameless people. He proposes to establish a DNA lab at the site, so that the bodies to be buried here may first be identified. He then proposes to trace and inform their families. Irrespective of religion, caste or creed the people that will be buried here, will face Makkah, amidst lush gardens of jasmine, date and bougainvillea in the city of Zarzis. Keeping the “Jardin d’Afrique” cemetery (Garden of Africa) in mind, the etching Koraichi has recently made, printed at the Cowasjee Print Studio, NCA; is also titled “Jardin d’Afrique”. With its profusion of symbols; of waves, figures, trees, stars, using the geometric shapes of the circle and the square, the image is both complex and visually stunning.]

LR: What is the relevance of the primal elements of in your work?

RK: Fire turns clay into ceramic…iron, bronze [in sculptures], stone…water shapes the stones, [also used for cutting it]. It is the connectivity to family and continuity, for me. My book, “Water is too far for Fire which is Too Near”,…original text plus prints…there are forty nine original prints in the book, the mystic number seven multiplied by seven is forty nine. And the book is an edition of fifty. The original text is in French. It has also been translated into Spanish.

LR: Working on the textile pieces, there appear to be references to wars.

RK: Not wars, no. These are references to ancestors and eternity. I have done these for my ancestors, as a tribute. Like flags are distinctive symbols, to connect, to identify [clans, tribes] from the Holy Prophet’s (PBUH) time. Flags announced the arrival of the Holy Prophet (PBUH) when he traveled, for instance.

Like scarification, tattoos are distinctive symbols which we understand and read, to connect and identify with people from different tribes, to differentiate from one to another – not a separation but to distinguish. A symbol to identify within themselves as well…the differences of cultures, not against each other. In this way we have the passage from childhood to adulthood to old age, just to distinguish, not separate.

[LR: In the textiles displayed in the Lahore Museum, there are symbols of the hand (the alam), eyes, stars, date palms, rivers or seas, women, men, crescents; appliqued and stitched in rich silk and gold embroidery, as a tribute to the three revealed religions, with the intention of highlighting the many similarities between the three.]

LR: Do you see your own art practice as something that is a unifying force between East and West?

RK: It is a big pretension to claim that. The idea…like a spark…there’s always a context. Referring to the dead Algerians of the Resistance 1830s, buried in a mass grave at the Chateau d’Amboise, I made the “Jardin d’Orient”. The catalyst for this was that I was praying there one day. A woman’s pet dog came near me and peed near my feet. “Who are you?” she asked me. I said that I was Rachid Koraichi. She said, “Are you working here? My dog has the habit of peeing here since a long time.” My response was, “At least you’re sincere and honest in telling me this!”

This moment led to my thinking of making the cemetery [Jardin d’Orient”]. So, the dog was the catalyst. It was also “maktoob” - destiny, fate. Choices we make and don’t make…like being at a crossroads.

[The “Jardin d’Orient” created by Rachid Koraichi is a cemetery in tribute to the martyrs who were buried in a mass grave here; of the 1880s war, between Algeria and Syria. This lies in the gardens of the Chateau d’Amboise in France, one of the palaces of Francois I, of France. It is comprised of blocks of stone with carving near their top rims, referencing the Ka’aba. A construction of a metal form, a medallion of text and symbols, tops these blocks, but this form is only easily readable when it casts its’ shadow onto the surface of the block. A line of seven cypress trees edges this harmonious space. A diagonal line of sage bushes, cuts through the grave blocks, which points in the direction of Makkah. Nearby the tomb of Leonardo da Vinci stands as a witness to this space.]

LR: Where do you situate yourself vis-a-vis individuality?

RK: My family lived in the desert, before Sufism, where you can’t live alone. Any family has to live in a community. I am currently living in my family home, in the desert. In the world there are 300 million Tijanis. I live in the company of Sufis. Someone who tells you “I am a Sufi” is not a Sufi.

***

Rachid Koraichi enriched the hearts and minds of all whom he came into contact with during the Lahore Biennale 02, this year. The stories he weaves in his work – whether it is a ceramic bowl or a bronze sculpture of a man, made up of intricate swirls of Arabic text, be it a play on the shadow or symbols adorning a huge tapestry – show that all his work is imbued with philosophical purpose, complexity and strength.

With grateful thanks to Nadia Khawaja for translating the French and Prof. Naazish Ata-Ullah, in whose living room the interview was conducted. All imperfections in translation are mine alone.

Laila Rahman is an artist and teaches at the National College of Arts, Lahore