It often takes a generation to change the strategic thinking of the military, much as it takes miles for a large cargo ship to alter course.

Consider the case of France’s top army leadership during the period 1870-1939. They fought three wars against Germany, all of which France lost before being bailed out by its allies in the First and Second World Wars. In each conflict, the French changed their defence strategy to counter innovations the Germans had introduced in the previous one. Each time, the Germans countered by switching plans again, wrong-footing their adversaries once more.

And each time, it was the young officers and troops who paid with their lives and limbs. This myopia among the top brass has cost the world much in blood and treasure, and yet the slaughter goes on. Of course the fog of war has served as an excuse for poor leadership throughout military history, but there are factors that could have been taken into account. This hubris and a refusal to learn has caused generations of brave young men to be killed.

Our own brass has little to be proud of - having lost every conflict they have been involved in. After each defeat, they have blamed politicians for their multiple failings, while ignoring the most basic tactical and strategic missteps. For example, take the launch of an armoured strike by our newly acquired Patton tanks near Sialkot during the 1965 war. The Indians simply cut the canals in the area, thereby flooding the battlefield and causing our tanks to get completely stuck. You could almost hear our generals grumbling that this tactic wasn’t very sporting of the Indians.

But the worst example of poor planning and execution comes from Kargil, a conflict that caused more casualties than the 1965 and 1971 wars put together. General Musharraf, the architect of this harebrained operation, prided himself as a strategist. However, grand strategy does not demand just an awareness of the immediate battlefield, but a grasp of the global environment. Basically, the top commanders need to understand the decision-making processes and possible reactions in key world capitals. Above all, they need to be on the same page as their military colleagues and their political masters.

In the case of the Kargil conflict, as Nasim Zehra shows us in her brilliantly researched book From Kargil to the Coup: Events that Shook Pakistan, none of these basic preconditions were in place. This book should be required reading for all those who want to learn how and why we went to war, and perhaps more importantly, about the poisonous effects of the constant friction between the military and civilian leadership.

The Kargil operation was aimed primarily to cut the Indian supply route to the Siachen Glacier. But a subplot here was the search for vengeance for India grabbing the glacier in the first place. And then, of course, there was the desire to force India to negotiate a settlement to solve the Kashmir issue once and for all.

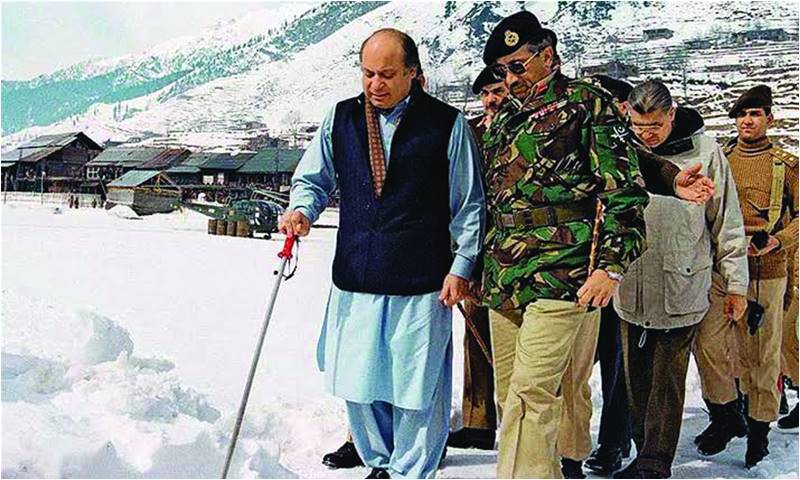

This high-risk, high-return operation had been put into cold storage earlier. But Musharraf, on being appointed by Nawaz Sharif in 1998, began secretly looking at the possibilities of a bold, covert sally across the Line of Control in the Drass region offered.

The fiction used as cover throughout the operation was that the intruders were freedom fighters over whom Pakistan had little control. The reality was that apart from being untrained in high-altitude operations, the Mujahideen were too undisciplined to sustain a long, arduous campaign at over 14,000 feet on some of the most inhospitable terrain in the world. The solution was to send in jawans of the Northern Light Infantry, and pretend they were freedom fighters. One result of this deceit was that for some time after the operation ended, Pakistan refused to accept the bodies of our martyred troops, causing great distress and anger among relatives and survivors. best cordless dustbuster for 2020

When Bill Clinton imposed a pullout of our forces, fury in army messes and barracks exploded, and there was almost a mutiny against the top brass as well as the political leadership. Although Musharraf had given Sharif his “professional guarantee” that the operation could not possibly fail, it was now the PM who was facing the wrath of the opposition, the media and the military for selling out the victorious ‘Mujahideen.’

Musharraf and his co-plotters were sitting pretty, passing the blame to the elected government as earlier generals have done every time they have been defeated. The endgame resulted in Nawaz Sharif’s ouster. The military had won out – again – while politicians were taught not to mess with the establishment.

Neither Sharif nor Musharraf emerge well from this account: the former comes across as somebody with a limited attention span, easily amenable to flattery. The army chief appears to be shallow, and incapable of acknowledging his blunders. With this combination, it is small wonder that Kargil was such a disaster.

Consider the case of France’s top army leadership during the period 1870-1939. They fought three wars against Germany, all of which France lost before being bailed out by its allies in the First and Second World Wars. In each conflict, the French changed their defence strategy to counter innovations the Germans had introduced in the previous one. Each time, the Germans countered by switching plans again, wrong-footing their adversaries once more.

And each time, it was the young officers and troops who paid with their lives and limbs. This myopia among the top brass has cost the world much in blood and treasure, and yet the slaughter goes on. Of course the fog of war has served as an excuse for poor leadership throughout military history, but there are factors that could have been taken into account. This hubris and a refusal to learn has caused generations of brave young men to be killed.

Musharraf, on being appointed by Nawaz Sharif in 1998, began secretly looking at the possibilities of a bold, covert sally across the Line of Control

Our own brass has little to be proud of - having lost every conflict they have been involved in. After each defeat, they have blamed politicians for their multiple failings, while ignoring the most basic tactical and strategic missteps. For example, take the launch of an armoured strike by our newly acquired Patton tanks near Sialkot during the 1965 war. The Indians simply cut the canals in the area, thereby flooding the battlefield and causing our tanks to get completely stuck. You could almost hear our generals grumbling that this tactic wasn’t very sporting of the Indians.

But the worst example of poor planning and execution comes from Kargil, a conflict that caused more casualties than the 1965 and 1971 wars put together. General Musharraf, the architect of this harebrained operation, prided himself as a strategist. However, grand strategy does not demand just an awareness of the immediate battlefield, but a grasp of the global environment. Basically, the top commanders need to understand the decision-making processes and possible reactions in key world capitals. Above all, they need to be on the same page as their military colleagues and their political masters.

In the case of the Kargil conflict, as Nasim Zehra shows us in her brilliantly researched book From Kargil to the Coup: Events that Shook Pakistan, none of these basic preconditions were in place. This book should be required reading for all those who want to learn how and why we went to war, and perhaps more importantly, about the poisonous effects of the constant friction between the military and civilian leadership.

The Kargil operation was aimed primarily to cut the Indian supply route to the Siachen Glacier. But a subplot here was the search for vengeance for India grabbing the glacier in the first place. And then, of course, there was the desire to force India to negotiate a settlement to solve the Kashmir issue once and for all.

This high-risk, high-return operation had been put into cold storage earlier. But Musharraf, on being appointed by Nawaz Sharif in 1998, began secretly looking at the possibilities of a bold, covert sally across the Line of Control in the Drass region offered.

The fiction used as cover throughout the operation was that the intruders were freedom fighters over whom Pakistan had little control. The reality was that apart from being untrained in high-altitude operations, the Mujahideen were too undisciplined to sustain a long, arduous campaign at over 14,000 feet on some of the most inhospitable terrain in the world. The solution was to send in jawans of the Northern Light Infantry, and pretend they were freedom fighters. One result of this deceit was that for some time after the operation ended, Pakistan refused to accept the bodies of our martyred troops, causing great distress and anger among relatives and survivors. best cordless dustbuster for 2020

When Bill Clinton imposed a pullout of our forces, fury in army messes and barracks exploded, and there was almost a mutiny against the top brass as well as the political leadership. Although Musharraf had given Sharif his “professional guarantee” that the operation could not possibly fail, it was now the PM who was facing the wrath of the opposition, the media and the military for selling out the victorious ‘Mujahideen.’

Musharraf and his co-plotters were sitting pretty, passing the blame to the elected government as earlier generals have done every time they have been defeated. The endgame resulted in Nawaz Sharif’s ouster. The military had won out – again – while politicians were taught not to mess with the establishment.

Neither Sharif nor Musharraf emerge well from this account: the former comes across as somebody with a limited attention span, easily amenable to flattery. The army chief appears to be shallow, and incapable of acknowledging his blunders. With this combination, it is small wonder that Kargil was such a disaster.