By any reckoning 2019 was a terrible year for Pakistanis of all classes.

Consider, first, the state of the economy.

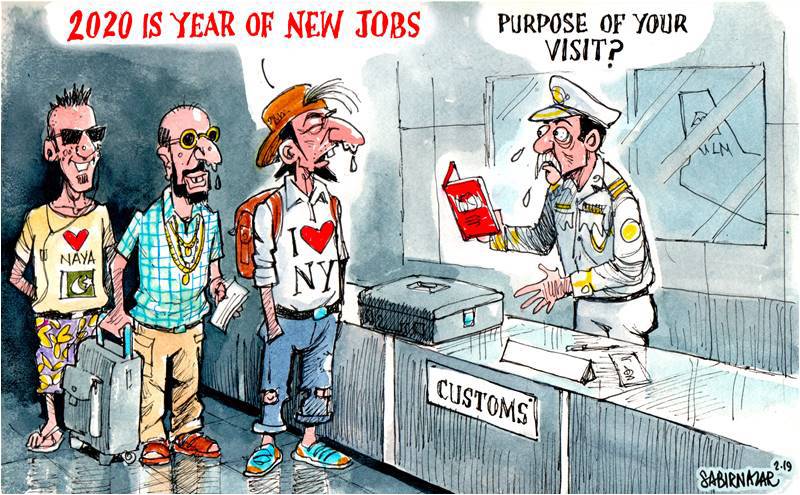

The PTI government opted for an IMF program of “stabilization” that increased taxes, interest rates and prices of petroleum products. The rupee was devalued by 30%, leading to 15% inflation because the economy is heavily import-dependent both for consumer goods and producer goods. This reduced consumer demand, slowed down industrial growth, eroded the buying power of the lower and middle classes and increased the impoverishment of the masses. The government had promised to absorb 1.5 million new entrants in to the job market. But real and disguised unemployment have risen significantly with a halving of GDP growth.

Although tax revenues have increased significantly, the burden of debt servicing, defense expenditures and leakages in the public sector economy have taken a toll on poverty alleviation measures, social sector and infrastructure priorities and circular debt targets. The fiscal deficit is running at record high levels, fueling inflation and debt. Devaluation has not led to any significant increase in exports and the balance of payments crisis has not subsided significantly.

Under the circumstances, the economic outlook for 2020 remains grim. Hot money aside, the prospects of foreign or domestic investment spurring growth are dim. Even CPEC funds are likely to taper off as scrutiny and conditionalities are imposed to account for competitiveness and dependency. And any external shock – like an increase in international oil prices, deterioration in ties with America, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf, or a military conflict with India – will impose further strains and hardships.

Consider, now, the state of political development and democracy that are prerequisites for economic certainty, stability and growth.

Government-Opposition relations have hit rock bottom. The top leaders of the mainstream parties, PPP and PMLN, are in prison or exile or enforced hospitalization. Parliament is dysfunctional – the government’s preferred route to law making is through short-lived Presidential Ordinances, the working committees are non-existent or deadlocked, the leaders of the House and Opposition are perennially absent and debate is viciously personal. The only thought of reform pertains to the longevity of the term of the army chief as a misplaced security blanket against any direct military intervention.

The media and judiciary as the third and fourth pillars of the state are in a state of siege. Unprecedented censorship, threats, shutdowns and blackmail have laid them low. Even social media activists are threatened with disappearances and shakedowns. The government and Miltablishment have turned a deaf ear to critical appreciation for better governance.

Under the circumstances, this state of siege may continue into 2020 if the government and Miltablishment remain on the “same page”, overwhelmed by 5G war conspiracy theories.

The state of external relations is also uncertain.

Relations with America depend on the Pakistani Miltablishment’s ability to deliver both an “honourable” exit of US troops from Afghanistan and a “workable” formula to end the civil war among the Afghans so that some sort of stable national government comprising all the major stakeholders that is not anti-West is possible. While the first objective may be achieved only because President Donald Trump is ready, in the final analysis, to withdraw unilaterally, the second is unlikely. In the last two decades, the Taliban have demonstrated the will and firepower to hold out for nothing less than full control of Afghanistan. They are unikely to abandon their gains on the eve of a grand and historic victory. This will put Pakistan in the uncomfortable position of having to mediate Western demands to “do more” vis-à-vis a resurgent Taliban regime.

Relations with India will be even more problematic. Given Narendra Modi’s Hindutva agenda and his propensity to whip up anti-Muslim and anti-Pakistan sentiment, the probability of a military conflict along the LoC and even the international border is high. Certainly, the greater the civil society resistance in India to his Hinduisation project, the greater the chances that he will seek to dilute and distract his detractors by bogeying Pakistan. However limited, such a conflict will impose another burden on Pakistan’s economy. More ominously, if the conflict leads to some sort of military setback for Islamabad, it will shake up the “same page” political dispensation and unleash political turmoil, with unforeseen consequences.

Conflict in the Middle East will also hurt Pakistan by straining its relations with the contending Muslim nations. Saudi Arabia and the Gulf kingdoms are very prickly about Pakistan’s relations with Iran and Turkey. Pakistan’s tightrope act involves joining the former because they give money and oil and the latter because they support the cause of Kashmir. It doesn’t help that America, which holds the strings of FATF, has solidly lined up against Iran and views Turkey’s growing ties with Russia with hostility.

A national consensus on critical issues at home between government, opposition and Miltablishment would help avert many looming pitfalls for economy and society. But this logic has so far been lost on the PTI government. Indeed, pundits are not hopeful that any abiding lessons have been learnt and will be applied.

Consider, first, the state of the economy.

The PTI government opted for an IMF program of “stabilization” that increased taxes, interest rates and prices of petroleum products. The rupee was devalued by 30%, leading to 15% inflation because the economy is heavily import-dependent both for consumer goods and producer goods. This reduced consumer demand, slowed down industrial growth, eroded the buying power of the lower and middle classes and increased the impoverishment of the masses. The government had promised to absorb 1.5 million new entrants in to the job market. But real and disguised unemployment have risen significantly with a halving of GDP growth.

Although tax revenues have increased significantly, the burden of debt servicing, defense expenditures and leakages in the public sector economy have taken a toll on poverty alleviation measures, social sector and infrastructure priorities and circular debt targets. The fiscal deficit is running at record high levels, fueling inflation and debt. Devaluation has not led to any significant increase in exports and the balance of payments crisis has not subsided significantly.

Under the circumstances, the economic outlook for 2020 remains grim. Hot money aside, the prospects of foreign or domestic investment spurring growth are dim. Even CPEC funds are likely to taper off as scrutiny and conditionalities are imposed to account for competitiveness and dependency. And any external shock – like an increase in international oil prices, deterioration in ties with America, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf, or a military conflict with India – will impose further strains and hardships.

Consider, now, the state of political development and democracy that are prerequisites for economic certainty, stability and growth.

Government-Opposition relations have hit rock bottom. The top leaders of the mainstream parties, PPP and PMLN, are in prison or exile or enforced hospitalization. Parliament is dysfunctional – the government’s preferred route to law making is through short-lived Presidential Ordinances, the working committees are non-existent or deadlocked, the leaders of the House and Opposition are perennially absent and debate is viciously personal. The only thought of reform pertains to the longevity of the term of the army chief as a misplaced security blanket against any direct military intervention.

The media and judiciary as the third and fourth pillars of the state are in a state of siege. Unprecedented censorship, threats, shutdowns and blackmail have laid them low. Even social media activists are threatened with disappearances and shakedowns. The government and Miltablishment have turned a deaf ear to critical appreciation for better governance.

Under the circumstances, this state of siege may continue into 2020 if the government and Miltablishment remain on the “same page”, overwhelmed by 5G war conspiracy theories.

The state of external relations is also uncertain.

Relations with America depend on the Pakistani Miltablishment’s ability to deliver both an “honourable” exit of US troops from Afghanistan and a “workable” formula to end the civil war among the Afghans so that some sort of stable national government comprising all the major stakeholders that is not anti-West is possible. While the first objective may be achieved only because President Donald Trump is ready, in the final analysis, to withdraw unilaterally, the second is unlikely. In the last two decades, the Taliban have demonstrated the will and firepower to hold out for nothing less than full control of Afghanistan. They are unikely to abandon their gains on the eve of a grand and historic victory. This will put Pakistan in the uncomfortable position of having to mediate Western demands to “do more” vis-à-vis a resurgent Taliban regime.

Relations with India will be even more problematic. Given Narendra Modi’s Hindutva agenda and his propensity to whip up anti-Muslim and anti-Pakistan sentiment, the probability of a military conflict along the LoC and even the international border is high. Certainly, the greater the civil society resistance in India to his Hinduisation project, the greater the chances that he will seek to dilute and distract his detractors by bogeying Pakistan. However limited, such a conflict will impose another burden on Pakistan’s economy. More ominously, if the conflict leads to some sort of military setback for Islamabad, it will shake up the “same page” political dispensation and unleash political turmoil, with unforeseen consequences.

Conflict in the Middle East will also hurt Pakistan by straining its relations with the contending Muslim nations. Saudi Arabia and the Gulf kingdoms are very prickly about Pakistan’s relations with Iran and Turkey. Pakistan’s tightrope act involves joining the former because they give money and oil and the latter because they support the cause of Kashmir. It doesn’t help that America, which holds the strings of FATF, has solidly lined up against Iran and views Turkey’s growing ties with Russia with hostility.

A national consensus on critical issues at home between government, opposition and Miltablishment would help avert many looming pitfalls for economy and society. But this logic has so far been lost on the PTI government. Indeed, pundits are not hopeful that any abiding lessons have been learnt and will be applied.