“It reveals my secrets, however much I conceal in privacy

Poetry speaks with true accuracy”

(Shayiri Sach Bolti He)

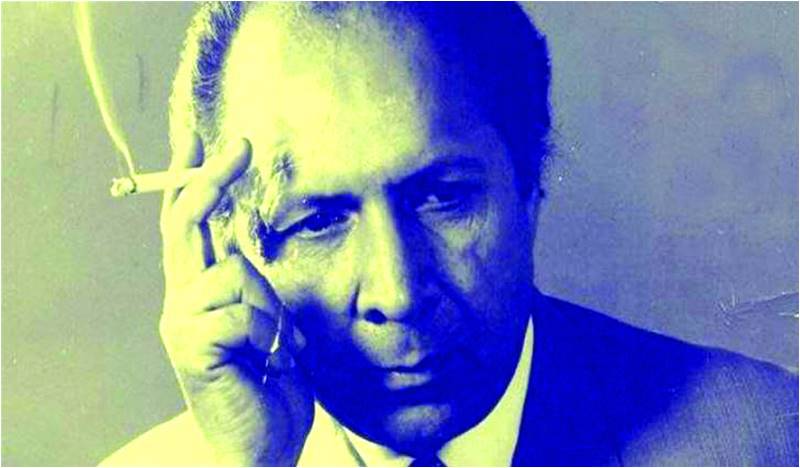

Amongst the ranks of Progressive poets, Qateel Shifai – born a hundred years ago earlier this week on the 24th of December in Haripur in what was then the North West Frontier Province, now Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa in Pakistan – belonged to that group which is romantic by temperament. It was what he saw as the demands of society at that time that led to him affiliating with the Progressive Writers. With Qateel, one finds the healthy romance of Punjab and those very poems determine his individuality which are about romantic emotions or present some aspect of the life of a woman. His poetry is light, lyrical poetry and his temperament seems to be in accordance with songs. In fact, he also wrote songs, and one collection of his songs was published as Haryali (Greenery). But it may be said that generally, the air of songs indeed dominated his poems and ghazals too.

His poems and ghazals are beautiful but their level is generally not too high. Like Majaz and Sahir, with him, too, there is no ambition to go beyond the destination of the prime of youth. Therefore his circle of thought is limited. Though he did write poems on political and national issues, but after wandering about, he remained attached to the mutriba (songstress), the tavaif (courtesan) and the adaakara (actress). So much so that:

“Nobody is satisfied

He is either angry or petrified

Pretty much like an unfaithful wife

Is it some prostitute, or indeed life?”

(Zindagi Ya Tavaif)

Sometimes he has tried to escape from the atmosphere of songs in his ghazals. The beauty of such ghazals cannot be denied:

“Where have the lovers from your party gone

What became of those stories you had made your own

Had those who left the temple and mosque not found the bar

Would the rejected folks have gone very far?

All is well that we put our madness to good use

Otherwise would its comprehension have needed a ruse?”

Or consider, for instance:

“The lips and cheeks are now the beneficiaries of respect

Even the freaks have reached my standard, I detect

Perhaps now the secret of your love will be revealed

To such courage of disclosure have the people of heart reached

There you are, concealing yourself like some god

Here we are, having reached the edge of the scaffold”

Among Qateel’s romantic poems, Harjai (Harlot), Khandar (Ruins), Pesh Goyi (Prediction), Raaste ka Phool (The Flower on the Road), Album, Baanjh (Barren Woman), Aaine ke Saamne (Before the Mirror); and among other types of poems, Tajdid (Renewal), Mashvara (Advice), Behlaave (Amusements) and Mera Qalam (My Pen) could be said to be his representative works.

Qateel was an entirely self-made poet, having struggled to make ends meet after the early death of his father and the consequent disruption of his education. He began by operating his own sports goods business, shifting to working for a transport company, before arriving in Lahore in the mid-1940s to try his luck. He formed a lasting friendship there with Ibne Insha, Arif Abdul Mateen, Sahir Ludhianvi, A. Hameed, Fikr Taunsvi and Ahmed Rahi. In those days, his love affair with a Hindu woman Chander Kanta was the subject of much scandal. She had not left for India after the 1947 Partition and lived in the same Royal Park building in which Qateel had moved with Rahi, Sahir, Hameed, Taunsvi and Mateen. Saadat Hasan Manto even wrote his short-story Mochna (Tweezer) on this woman because it was said that she had hair on her chest, which she used to pluck out with a tweezer.

In Lahore, Qateel initially found work as the assistant editor of the monthly Adab-e-Latif (whose longtime editor Siddiqa Begum passed away earlier this month), then began to edit the film weekly Adaakar (Actor). In those days, he was a handsome young man with thick black hair and a red-and-white complexion, full of life and poetic competence. Apart from love and romance, his poems and ghazals had a full consciousness of issues created by class contradictions.

“Should life play with the wind or remove hunger

If the belly is not full, is fidelity worth it any longer

What with the instruction to clothe a naked body, please

Without breath, what use is the wave of the breeze?”

His ghazal was the new voice of that era. He used to recite shining, tinkling and melodious verses (and continued to do so over his long life). He said what was clear and honest, and he was the life of the party because of his witty repartees. He dominated the world of ghazal in those days along with Abdul Hameed Adam. He was one of those poets who could steal a mushaira.

Qateel’s poem Chakle (Brothels) from his 1964 Adamjee Literary Award-winning collection Mutriba is lesser known than his comrade Sahir Ludhianvi’s 1949 poem of the same name, but in my humble opinion, the former preserves its devastating effect by being descriptive rather than prescriptive – which is how Sahir chooses to end his poem, thereby marring some of its beauty.

“Till late in the night, wounded songs here proclaim

This world belongs to the stone-hearted, no human can it claim

For the disgrace of the honourable, this is the biggest bazaar

Faith is sold here, along with the trade in honour

Should one beg indeed, even love one cannot have

But unasked one can get here provisions of disgrace

When the rich in the middle of songs, see the bodies dance

Often their every tune dissolves on a bed replete with fragrance

When the lips of a mother’s love are sealed with silver stamps

Here mothers themselves offer up their daughters as vamps

The blood of one’s own blood goes forth to bid a higher price

Who put a hand over whom, can one really recognize?

In this temple of sin, this daughter of Ram is really put to the test

When the gods of gold arrive in the waning sun to rest

Till late in the night does the dusky damsel wake

She will be called disobedient if she refuses the thieving black rakes

The shimmering dresses may indeed let off an odour so intense

Not surprisingly the party is made fragrant by the burning of incense”

In the preface to this collection, as if to anticipate his Progressive critics, Qateel wrote:

“I also know that until a new economic system does not arrive, bodies will continue to be sold within the cover of songs. Despite this, I am presenting my poems; not with the purpose of reform of society, but as good literature.”

Qateel was one poet who successively held his own in the domains of both poetry and film lyrics, in a crowded field boasting of the likes of Rashid, Faiz, Jan Nisar Akhtar, Majrooh Sultanpuri, Kaifi Azmi, Sahir and Ahmad Faraz. Unlike many other poets who compromised their poetic qualities and sensibilities after entering the film world, Qateel reigned supreme in both forms without losing his grip on either. He is also only the third poet after Sahir and Majrooh to have introduced progressive themes successively in his film work.

But why is it that just eighteen years after his death, he has been ignored by both the literary and the film worlds in the Indian Subcontinent? Surely a poet of Qateel’s stature deserves more in his centennial year? Granted that 2019 marked the centennials of many other illustrious contemporaries of Qateel like Kaifi, Amrita Pritam, Zaheer Kashmiri, Majrooh and Muhammad Hasan Askari, but dare I say that Qateel’s popularity outlasted all of these grandees because he did not write for – or appeal to – an exclusive lobby? Maybe it’s time that our so-called literary festivals and arts lobbies should heed what Qateel himself has said in a different context:

“Though myself I may be, but my art is no prisoner

My pen is not the conscience of any executioner” n

Note: All the translations from the Urdu are the writer’s own.

Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and award-winning translator and dramatic reader. He is currently based in Lahore, where he is also the President of the Progressive Writers Association. He can be reached at: razanaeem@hotmail.com