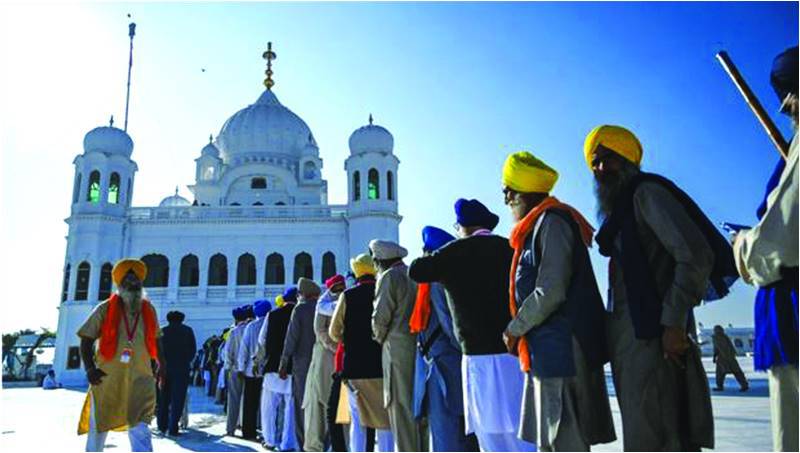

On November 9, the Kartarpur Corridor was inaugurated. After 72 years, the Sikhs living in India can now visit one of their holiest shrines, Dera Baba Nanak, the place chosen by their first guru, Guru Nanak, to settle down after his travels.

Pakistan has played a fabulous hand with this move at all levels: diplomatic, moral and humanitarian. India tried first to scuttle Pakistan’s initiative but was forced to play along in order to avoid being seen as the spoiler and losing face with the Sikh community. The negotiations were tough and tortuous but Pakistan kept pushing ahead — to the point where it did not let the talks subside despite India’s military aggression on the morning of February 26.

Even as the talks were going on, Pakistan was sprucing up the place, enlarging the area of the shrine, uplifting the buildings and preparing for the big day ahead of Guru Nanak’s 550th birth anniversary. November 9 proved how well that job was done.

That very same day saw a very different event, one more likely than Kartarpur to define Modi’s India. On that day, India’s Supreme Court announced its verdict on the Babri Mosque case. The mosque was demolished 27 years ago on December 6, 1992, by Hindutva activists mobilised by the Bharatiya Janata Party. But instead of preserving the rights of both parties, the Indian Supreme Court sought solace in solipsisms, and allowed the building of the Ayodhya temple to go ahead at the site of the Babri Mosque.

The timing could not have been more ironic. Pakistan, long accused by India of being a ‘theocratic’ state, was taking a big step towards inclusive pluralism at the very same moment as India, so fond of referring to itself as the world’s largest democracy, regressed even further into Hindutva exclusiveness.

Justice A.K. Ganguly, who retired from the Indian Supreme Court in 2012, denounced the verdict and told The Wire, an Indian online news outlet, the ruling had “placed a ‘premium’ on the mosque’s demolition.”

“If the Babri Masjid was not demolished, and Hindus went to court saying that Ram was born there, would the court have ordered it to be demolished?” [Ganguly] asked, adding, “[The court] would not have directed it.”

“The demolition had therefore been ‘given a premium’ by the Supreme Court in spite of the bench describing the act as a crime. He said that the judgment ‘encourages a very unfortunate trend… a totally non-secular trend’.”

The positivity of Kartarpur initiative has, therefore, to be seen in juxtaposition to the negativity of the Indian SC’s verdict on the Babri Mosque case. And therein lies the reality of today’s India and with it the unfortunate prognosis for South Asia. Consider.

Modi has so far capitalised on two factors to preserve India’s international image: the positive legacy of his predecessors, i.e., the image of India as a progressive, secular democracy and a large thriving market; its strategic location and emergence as a regional power to counterbalance China. While voices at the international level are now noting the changes happening in India, India’s diplomatic clout remains largely unaffected — for now.

The challenge for Pakistan is to help the world understand that it is now dealing with a growing monster of hate and bigotry. So far, Pakistan has not managed this well. Whatever opprobrium is coming India’s way is, ironically, because of what it is doing and which is being reported by international news outlets.

Take the case of occupied and now annexed Jammu and Kashmir (IOJK).

There are voices, new stories, op-eds in the international media. But barring exceptions, most criticism is directed towards the human rights situation in IOJK. Opinion makers as well as world leaders have called on India to restore the basic rights of the Kashmiris. That is only partial truth. The reality is more complex. The land does not belong to India. Its people have been denied one of the most basic and inalienable rights, the right to self-determination. Everything else flows from that.

When the international community calls on India to restore the human rights in IOJK, they tacitly accept India’s position that Kashmir is a part of India. So, the world asks India to take care of its people, to grant them constitutional rights, restore their status. That is not the solution; that is the problem. Kashmir is not India’s part. It is an occupied land.

The challenge for Pakistan is to make the world understand that (a) India is in occupation of IOJK; (b) India has illegally annexed the occupied land which it cannot; and, (c) that India’s occupation must end and the way to Kashmir’s liberation is for the Kashmiris to decide their own future by exercising their right to self-determination.

What is happening in IOJK today is the effect of that original denial, it’s not the cause. Kashmiris have consistently indicated, both through peaceful protests and occasional armed resistance, that they do not want to live with and in India. That position has been met with the full force of the Indian state’s coercion. The cycle has gone on. The only way to end this cycle is to address the central problem. That is the challenge.

The reason the Indian SC’s verdict in the Babri Mosque case is so important is because it is now clear to India’s beleaguered Muslim community and other minorities that the highest court in that land will endorse the majoritarian, Hindutva consensus and underwrite even the worst excesses of the Executive and Legislative branches of the government.

As former Justice A K Ganguly said to The Wire: “Now the Supreme Court says that underneath the mosque there was some structure. But there are no facts to show that that structure was a temple. The Supreme Court’s verdict says they don’t have evidence to say that a temple was demolished and a mosque was built. There could have been any structure below – a Buddhist stupa, a Jain structure, a church. But it may not have been a temple. So on what basis did the Supreme Court find that the land belongs to Hindus or to Ram Lalla?”

That basis goes back to the judicial murder of Afzal Guru in the Indian parliament attack case. The Indian SC’s verdict clearly stated that the court had to take cognisance of the national sentiment. Law, therefore, does not stand apart from politics, xenophobia, jingoism and faith in India. The situation, since then, has only got worse.

There are petitions before the Indian SC on Modi government’s unconstitutional and illegal annexation of IOJK. I have spoken with dozens of Kashmiris, asking them a simple question: Would the Indian SC do justice and restore status quo ante? To the last one the answer was no.

If nothing else, this widespread belief shows how utterly the hapless Kashmiris lack any faith in India’s highest court. And if the courts cannot address and neutralise the excesses of the executive, and if there’s no political avenue left for a people, what must they do to express themselves? This is a vital question even for the citizens of a state that resorts to oppression. It should not take much imagination for anyone except imbeciles and ultra-nationalists, usually interchangeable categories, to figure out how much more important this would be for a people whose land has been occupied.

The prognosis for South Asia doesn’t seem positive, notwithstanding the Kartarpur spirit of amity. Pakistan must continue on the trajectory it has found and retain its initiative. But can it do it alone? It takes one to make a row but two to make peace. The world needs to keep a close watch on what’s happening in India because the slide of 1.3 billion people into religious madness is a danger that can have untold unsavoury consequences.

The writer is a former News Editor of

The Friday Times. He tweets @ejazhaider reluctantly

Pakistan has played a fabulous hand with this move at all levels: diplomatic, moral and humanitarian. India tried first to scuttle Pakistan’s initiative but was forced to play along in order to avoid being seen as the spoiler and losing face with the Sikh community. The negotiations were tough and tortuous but Pakistan kept pushing ahead — to the point where it did not let the talks subside despite India’s military aggression on the morning of February 26.

Even as the talks were going on, Pakistan was sprucing up the place, enlarging the area of the shrine, uplifting the buildings and preparing for the big day ahead of Guru Nanak’s 550th birth anniversary. November 9 proved how well that job was done.

That very same day saw a very different event, one more likely than Kartarpur to define Modi’s India. On that day, India’s Supreme Court announced its verdict on the Babri Mosque case. The mosque was demolished 27 years ago on December 6, 1992, by Hindutva activists mobilised by the Bharatiya Janata Party. But instead of preserving the rights of both parties, the Indian Supreme Court sought solace in solipsisms, and allowed the building of the Ayodhya temple to go ahead at the site of the Babri Mosque.

The timing could not have been more ironic. Pakistan, long accused by India of being a ‘theocratic’ state, was taking a big step towards inclusive pluralism at the very same moment as India, so fond of referring to itself as the world’s largest democracy, regressed even further into Hindutva exclusiveness.

Justice A.K. Ganguly, who retired from the Indian Supreme Court in 2012, denounced the verdict and told The Wire, an Indian online news outlet, the ruling had “placed a ‘premium’ on the mosque’s demolition.”

“If the Babri Masjid was not demolished, and Hindus went to court saying that Ram was born there, would the court have ordered it to be demolished?” [Ganguly] asked, adding, “[The court] would not have directed it.”

“The demolition had therefore been ‘given a premium’ by the Supreme Court in spite of the bench describing the act as a crime. He said that the judgment ‘encourages a very unfortunate trend… a totally non-secular trend’.”

The positivity of Kartarpur initiative has, therefore, to be seen in juxtaposition to the negativity of the Indian SC’s verdict on the Babri Mosque case. And therein lies the reality of today’s India and with it the unfortunate prognosis for South Asia. Consider.

Modi has so far capitalised on two factors to preserve India’s international image: the positive legacy of his predecessors, i.e., the image of India as a progressive, secular democracy and a large thriving market; its strategic location and emergence as a regional power to counterbalance China. While voices at the international level are now noting the changes happening in India, India’s diplomatic clout remains largely unaffected — for now.

The challenge for Pakistan is to help the world understand that it is now dealing with a growing monster of hate and bigotry. So far, Pakistan has not managed this well. Whatever opprobrium is coming India’s way is, ironically, because of what it is doing and which is being reported by international news outlets.

Take the case of occupied and now annexed Jammu and Kashmir (IOJK).

There are voices, new stories, op-eds in the international media. But barring exceptions, most criticism is directed towards the human rights situation in IOJK. Opinion makers as well as world leaders have called on India to restore the basic rights of the Kashmiris. That is only partial truth. The reality is more complex. The land does not belong to India. Its people have been denied one of the most basic and inalienable rights, the right to self-determination. Everything else flows from that.

When the international community calls on India to restore the human rights in IOJK, they tacitly accept India’s position that Kashmir is a part of India. So, the world asks India to take care of its people, to grant them constitutional rights, restore their status. That is not the solution; that is the problem. Kashmir is not India’s part. It is an occupied land.

The challenge for Pakistan is to make the world understand that (a) India is in occupation of IOJK; (b) India has illegally annexed the occupied land which it cannot; and, (c) that India’s occupation must end and the way to Kashmir’s liberation is for the Kashmiris to decide their own future by exercising their right to self-determination.

What is happening in IOJK today is the effect of that original denial, it’s not the cause. Kashmiris have consistently indicated, both through peaceful protests and occasional armed resistance, that they do not want to live with and in India. That position has been met with the full force of the Indian state’s coercion. The cycle has gone on. The only way to end this cycle is to address the central problem. That is the challenge.

The reason the Indian SC’s verdict in the Babri Mosque case is so important is because it is now clear to India’s beleaguered Muslim community and other minorities that the highest court in that land will endorse the majoritarian, Hindutva consensus and underwrite even the worst excesses of the Executive and Legislative branches of the government.

As former Justice A K Ganguly said to The Wire: “Now the Supreme Court says that underneath the mosque there was some structure. But there are no facts to show that that structure was a temple. The Supreme Court’s verdict says they don’t have evidence to say that a temple was demolished and a mosque was built. There could have been any structure below – a Buddhist stupa, a Jain structure, a church. But it may not have been a temple. So on what basis did the Supreme Court find that the land belongs to Hindus or to Ram Lalla?”

That basis goes back to the judicial murder of Afzal Guru in the Indian parliament attack case. The Indian SC’s verdict clearly stated that the court had to take cognisance of the national sentiment. Law, therefore, does not stand apart from politics, xenophobia, jingoism and faith in India. The situation, since then, has only got worse.

There are petitions before the Indian SC on Modi government’s unconstitutional and illegal annexation of IOJK. I have spoken with dozens of Kashmiris, asking them a simple question: Would the Indian SC do justice and restore status quo ante? To the last one the answer was no.

If nothing else, this widespread belief shows how utterly the hapless Kashmiris lack any faith in India’s highest court. And if the courts cannot address and neutralise the excesses of the executive, and if there’s no political avenue left for a people, what must they do to express themselves? This is a vital question even for the citizens of a state that resorts to oppression. It should not take much imagination for anyone except imbeciles and ultra-nationalists, usually interchangeable categories, to figure out how much more important this would be for a people whose land has been occupied.

The prognosis for South Asia doesn’t seem positive, notwithstanding the Kartarpur spirit of amity. Pakistan must continue on the trajectory it has found and retain its initiative. But can it do it alone? It takes one to make a row but two to make peace. The world needs to keep a close watch on what’s happening in India because the slide of 1.3 billion people into religious madness is a danger that can have untold unsavoury consequences.

The writer is a former News Editor of

The Friday Times. He tweets @ejazhaider reluctantly