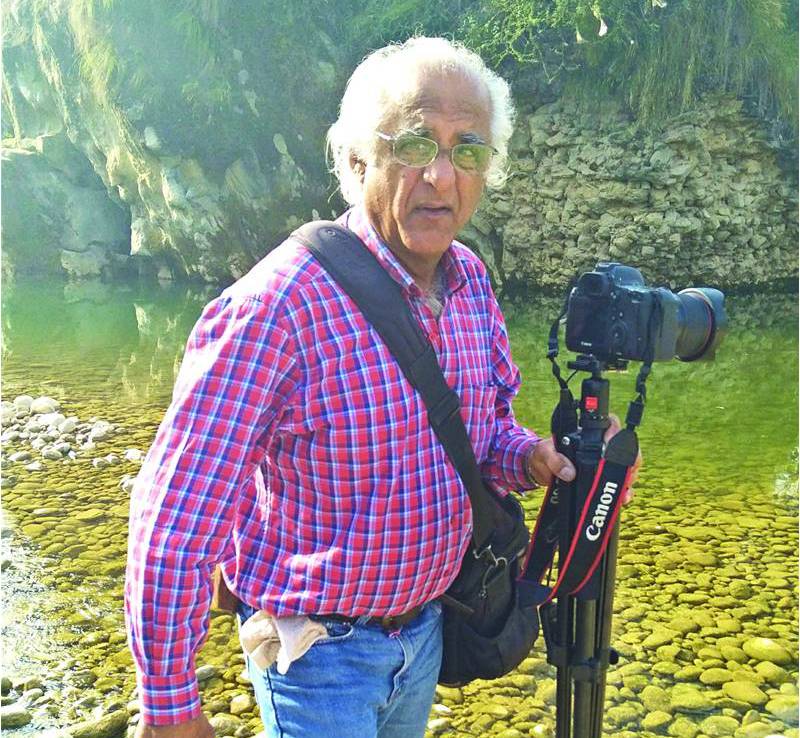

He is a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and one of few authorities on the Indian expedition of Alexander the Great. It often seems as if he has traveled every inch of Pakistan. And he is the only Pakistani to have seen the north face of K-2.

With every word of his travelogues, he cajoles and coaxes readers to travel to these places where he has been. There is cinematic storytelling ornamented with charming prose. The reader is instantly captivated when it comes to his writing, accompanied by his photography skills.

He has been talking about lesser known but fascinating sites in Pakistan since the past 40 years.

From the lush green Deosai plains to the scenic beaches of Balochistan, and from the ravines of the red granite Karoonjhar hills on eastern border with India to the bleak salt pans of Mashkel on the Iranian border, there are few places in Pakistan that remain untouched by his feet. He trekked 1,100 km “between two burrs of the map”, the Karakorum and Hindukush mountains.

Salman Rashid’s travel accounts are a logical and scholarly mix of history, geography, sociology, folklore, anthropology and high adventure. Above all, he has a flair for humour.

One moment he might be quoting from Peter Fleming or Robert Byron. Next he might offer a sip of Mushtaq Yousufi, with Norman Lewis word power. Nothing feels strange when he recites couplets of Iqbal, Mir or Ghalib. He often cites verses from the latter at book-signing events, in his perfectly Punjabi accent!

Apart from his hundreds of features for many leading English newspapers and periodicals, he has to his credit a number of books, including a memoir of the 1947 Partition. His titles include:

- Riders on the Wind (1990)

- Gujranwala: The Glory That Was (1992)

- Between Two Burrs on the Map :Travels in Northern Pakistan (1995)

- Prisoners on a Bus (1997)

- Sea monsters and the Sun god (1999)

- The Salt Range & The Pothohar Plateau (2001)

- Jhelum: City of the Vitasta (2005)

- Deosai: Land of the Giant (2011)

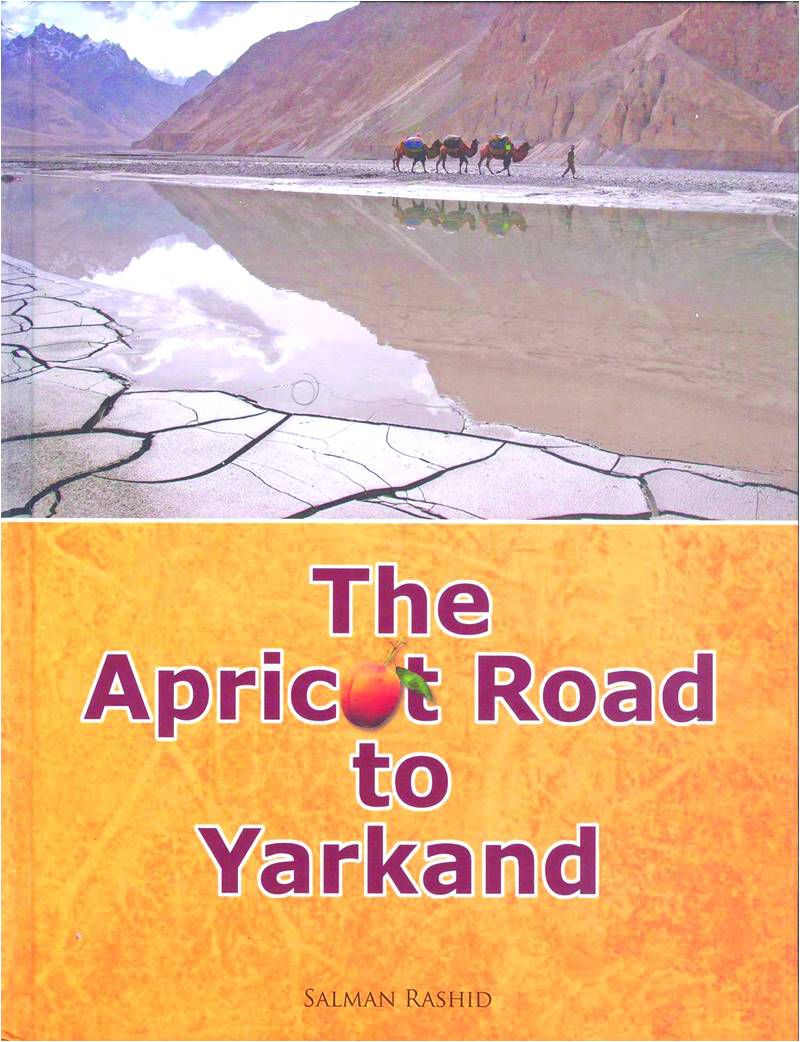

- The Apricot Road to Yarkand (2013)

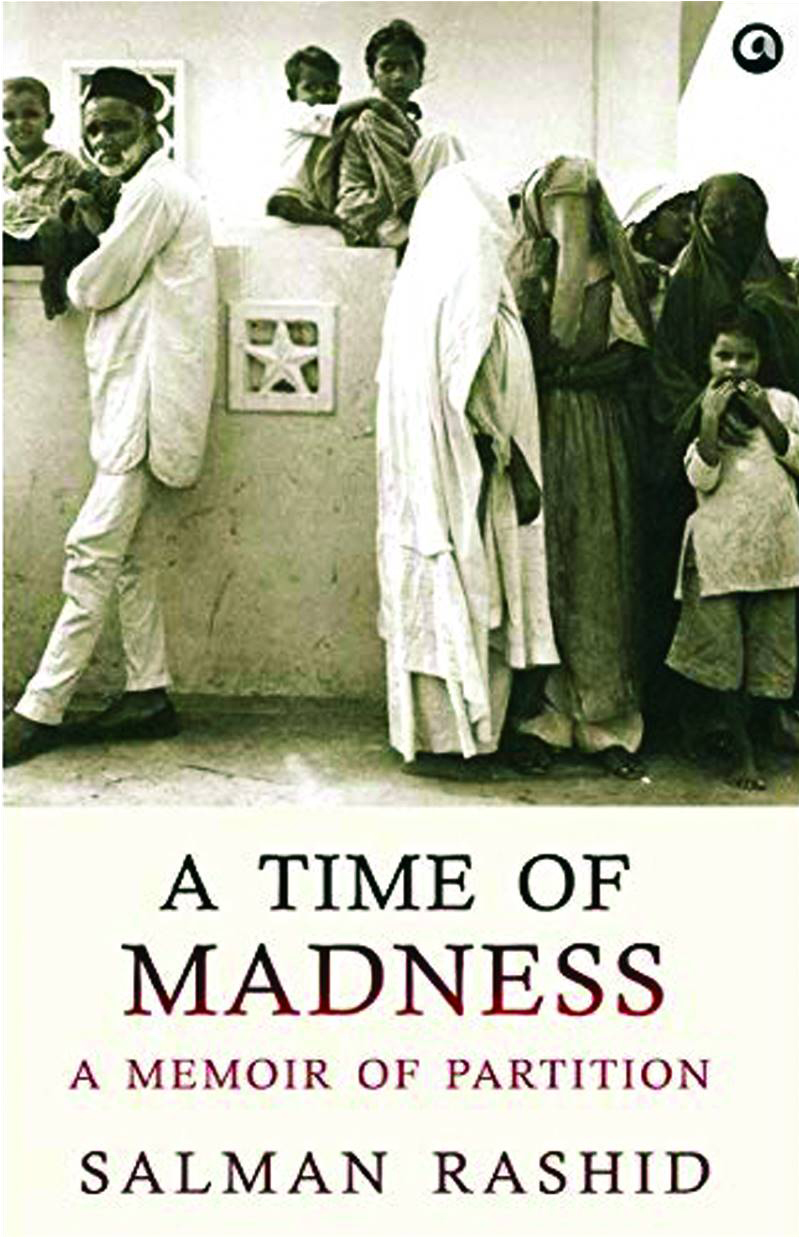

- A Time of Madness: A Memoir of Partition (2017)

- Nagarparkar (upcoming book)

Ammad Ali: Was it due to your career as a young soldier in the Army that you became an adventurer and traveler?

Salman Rashid: No, I had germs of wanderlust long ago before joining the Army [laughs]. The earliest signs were my interest in maps and atlases. In my teens I used to be keen on finding different places and geographies on maps. Even during my early days in the Army when I was posted at Lala Musa, I had access to powerful binoculars and I spent a whole day seeing the historic Tilla Jogian hill from my station. I decided to trek to the hill and spent the night there. My rebellious nature eventually pushed to resign from the life of a soldier and I decided to join the profession of my elders. Being Arain (an agrarian tribe of Punjab and Sindh), farming and agriculture made sense to me. But I learned that our canal-irrigated agricultural land had been sold. Those were hard times. I moved to Karachi and got a job in a private company there. In Karachi I walked areas of the city on foot and explored many parts of Sindh. I could probably claim with some justification that I got to see more of Sindh than many Sindhis.

AA: So It was during a later period that you discovered your ability to tell a story and then your travel tales began to appear in print?

SR: One day I went to the Pakistan Tourism Development Corporation (PTDC) office to seek their help in learning more about the heritage of Sindh. I was introduced to a lady who persuaded – even dragged me – into writing. Her name is Talat Rahim. PTDC then used to publish a magazine named Focus On Pakistan. It was where my first feature appeared, and it was about the Ranikot fort. From that day I never stopped writing. For my first feature I borrowed a camera from a friend. Later I contributed to PIA’s Humsafar magazine. In 1986, I commenced writing for STAR, an evening paper of Dawn. Sania Hassan, who I knew earlier, was a staffer at STAR and I was introduced to journalists like Zohra Yusuf. In 1988, I came back to Lahore and start contributing to the Pakistan Times. It was a great learning opportunity also to work with I.A Rehman. When Beena Sarwar launched the weekly magazine of The News, i.e. The News on Friday (later The News on Sunday) the paper offered me a golden opportunity, not only by commissioning my weekly feature but also to bear the expenses of my travel. That was the first time any paper funded my travels. I wrote for more than 20 years for them. Along with this, I also worked for WWF – activism centred around the environment and climate change has been my forte. Now I am writing for Dawn’s EOS.

AA: How was your experience when “Nagri Nagri Ghoom Musafir” aired on state television in the 1990s? Before that, you were known to a specific English-reading class. Did you feel a sense of difficulty, perhaps even some censorship, given that it was state television and many historical facts go against our state’s official narrative? Was it difficult?

SR: Thanks to Muneeza Hashmi, who was then General Manager of Pakistan Television Corporation (PTV ) Lahore, we enjoyed a great deal of freedom. I had no restrictions on me. I had this project in my mind since 1994 but that General Manager – I won’t say they were unwilling – ended up delaying it for four years. Finally in 1998 when Muneeza Hashmi was General Manager, “Nagri Nagri Ghoom Musafir” aired on television and it continued until 1999. Later again in 2001, when she was GM, I came up with the idea of Alexander’s campaign in North West India and thus “Sindhya Main Sikander” aired. In this programme I followed the steps of Alexander’s route and explained where he stayed and where he battled. During my research on Alexander I found that there was not sufficient literature on him. Many academics never touched this topic. Robin Lane Fox’s work on Alexander is admirable and I recommend his books. Unfortunately in Pakistan, anyone who talks of Alexander “with authority” has only hearsay to rely on. There are fabricated stories and false histories constructed over a period of time about Alexander’s travel to India by local writers and historians. Alexander and his Indian incursion have not been properly documented because reading him seems to be difficult for most people here. No one has read his history in Pakistan, it seems.

AA: How does your process of writing begin, generally?

SR: I begin my process of writing after I have been to a site. But in a way, it begins even before – if I happen to read about some place and plan a visit, etc. There are many places in Pakistan where I traveled twice or thrice. It is, therefore, at times a comparison between an earlier visit and a more recent one – an account of how heritage and geography transform over a period of time. For instance, I visited Pharwala Fort in 1993 for the first time. It has a rich history associated with it. Later, I went there in 2015 and found that, sadly, locals had begun dismantling that heritage. I had photos of my first visit and the last visit to compare. Recently I am writing a book on Nagarparkar. I went there for the first time in 1984 and again two years ago. I saw the changes in the lives of the locals and their relationship with their heritage. Sometimes I have to read a lot, just like for my book, The Salt Range & The Pothohar Plateau. I read hundreds of books because the area has a rich history and sites of interest range from ancient Taxila to the Hindu forts of the Salt Range.

AA: How do you see travel writing in Pakistan? Does it will help to promote tourism, given how that sector appears to be a priority of the present government?

SR: Be assured that travel writing is not even considered a genre of writing in Pakistan. Travel writing in newspapers, unfortunately, is only an account of the family vacation to Murree. There is no other professional travel writer. The cost is too high and dividends too low. Only a lunatic would want to be one! We must remember that a travel writer has to be a geographer, historian, anthropologist, sociologist and last of all an autobiographer. Now, to be the first two, one has to read, read, read and read. Pakistanis simply do not read. Their only reading is for exams, not for edification.

The bottom line is that travel writing is dead in Pakistan. Yes, travel writing promotes tourism because it covers more details than a Vlog or recent Youtuber culture in which they often have very little knowledge of the history and geography of a specific place.

I do not see a ray of hope that recent steps by the government would be successful in bringing tourists to Pakistan. For that to work, you will need long-term planning, preservation of our heritage and the establishment of spaces that are friendly to Western tourists. For instance, We are told that they changed the visa policy to bring in more tourists. But look at the list of countries for that softer new visa policy – many of them are places from where we are unlikely to receive many visitors, as their citizens generally don’t even know the name of Pakistan!

With every word of his travelogues, he cajoles and coaxes readers to travel to these places where he has been. There is cinematic storytelling ornamented with charming prose. The reader is instantly captivated when it comes to his writing, accompanied by his photography skills.

He has been talking about lesser known but fascinating sites in Pakistan since the past 40 years.

From the lush green Deosai plains to the scenic beaches of Balochistan, and from the ravines of the red granite Karoonjhar hills on eastern border with India to the bleak salt pans of Mashkel on the Iranian border, there are few places in Pakistan that remain untouched by his feet. He trekked 1,100 km “between two burrs of the map”, the Karakorum and Hindukush mountains.

Salman Rashid’s travel accounts are a logical and scholarly mix of history, geography, sociology, folklore, anthropology and high adventure. Above all, he has a flair for humour.

“In Pakistan, anyone who talks of Alexander ‘with authority’ has only hearsay to rely on. There are fabricated stories and false histories constructed over a period of time by local writers and historians”

One moment he might be quoting from Peter Fleming or Robert Byron. Next he might offer a sip of Mushtaq Yousufi, with Norman Lewis word power. Nothing feels strange when he recites couplets of Iqbal, Mir or Ghalib. He often cites verses from the latter at book-signing events, in his perfectly Punjabi accent!

Apart from his hundreds of features for many leading English newspapers and periodicals, he has to his credit a number of books, including a memoir of the 1947 Partition. His titles include:

- Riders on the Wind (1990)

- Gujranwala: The Glory That Was (1992)

- Between Two Burrs on the Map :Travels in Northern Pakistan (1995)

- Prisoners on a Bus (1997)

- Sea monsters and the Sun god (1999)

- The Salt Range & The Pothohar Plateau (2001)

- Jhelum: City of the Vitasta (2005)

- Deosai: Land of the Giant (2011)

- The Apricot Road to Yarkand (2013)

- A Time of Madness: A Memoir of Partition (2017)

- Nagarparkar (upcoming book)

***

Ammad Ali: Was it due to your career as a young soldier in the Army that you became an adventurer and traveler?

Salman Rashid: No, I had germs of wanderlust long ago before joining the Army [laughs]. The earliest signs were my interest in maps and atlases. In my teens I used to be keen on finding different places and geographies on maps. Even during my early days in the Army when I was posted at Lala Musa, I had access to powerful binoculars and I spent a whole day seeing the historic Tilla Jogian hill from my station. I decided to trek to the hill and spent the night there. My rebellious nature eventually pushed to resign from the life of a soldier and I decided to join the profession of my elders. Being Arain (an agrarian tribe of Punjab and Sindh), farming and agriculture made sense to me. But I learned that our canal-irrigated agricultural land had been sold. Those were hard times. I moved to Karachi and got a job in a private company there. In Karachi I walked areas of the city on foot and explored many parts of Sindh. I could probably claim with some justification that I got to see more of Sindh than many Sindhis.

AA: So It was during a later period that you discovered your ability to tell a story and then your travel tales began to appear in print?

SR: One day I went to the Pakistan Tourism Development Corporation (PTDC) office to seek their help in learning more about the heritage of Sindh. I was introduced to a lady who persuaded – even dragged me – into writing. Her name is Talat Rahim. PTDC then used to publish a magazine named Focus On Pakistan. It was where my first feature appeared, and it was about the Ranikot fort. From that day I never stopped writing. For my first feature I borrowed a camera from a friend. Later I contributed to PIA’s Humsafar magazine. In 1986, I commenced writing for STAR, an evening paper of Dawn. Sania Hassan, who I knew earlier, was a staffer at STAR and I was introduced to journalists like Zohra Yusuf. In 1988, I came back to Lahore and start contributing to the Pakistan Times. It was a great learning opportunity also to work with I.A Rehman. When Beena Sarwar launched the weekly magazine of The News, i.e. The News on Friday (later The News on Sunday) the paper offered me a golden opportunity, not only by commissioning my weekly feature but also to bear the expenses of my travel. That was the first time any paper funded my travels. I wrote for more than 20 years for them. Along with this, I also worked for WWF – activism centred around the environment and climate change has been my forte. Now I am writing for Dawn’s EOS.

AA: How was your experience when “Nagri Nagri Ghoom Musafir” aired on state television in the 1990s? Before that, you were known to a specific English-reading class. Did you feel a sense of difficulty, perhaps even some censorship, given that it was state television and many historical facts go against our state’s official narrative? Was it difficult?

SR: Thanks to Muneeza Hashmi, who was then General Manager of Pakistan Television Corporation (PTV ) Lahore, we enjoyed a great deal of freedom. I had no restrictions on me. I had this project in my mind since 1994 but that General Manager – I won’t say they were unwilling – ended up delaying it for four years. Finally in 1998 when Muneeza Hashmi was General Manager, “Nagri Nagri Ghoom Musafir” aired on television and it continued until 1999. Later again in 2001, when she was GM, I came up with the idea of Alexander’s campaign in North West India and thus “Sindhya Main Sikander” aired. In this programme I followed the steps of Alexander’s route and explained where he stayed and where he battled. During my research on Alexander I found that there was not sufficient literature on him. Many academics never touched this topic. Robin Lane Fox’s work on Alexander is admirable and I recommend his books. Unfortunately in Pakistan, anyone who talks of Alexander “with authority” has only hearsay to rely on. There are fabricated stories and false histories constructed over a period of time about Alexander’s travel to India by local writers and historians. Alexander and his Indian incursion have not been properly documented because reading him seems to be difficult for most people here. No one has read his history in Pakistan, it seems.

AA: How does your process of writing begin, generally?

SR: I begin my process of writing after I have been to a site. But in a way, it begins even before – if I happen to read about some place and plan a visit, etc. There are many places in Pakistan where I traveled twice or thrice. It is, therefore, at times a comparison between an earlier visit and a more recent one – an account of how heritage and geography transform over a period of time. For instance, I visited Pharwala Fort in 1993 for the first time. It has a rich history associated with it. Later, I went there in 2015 and found that, sadly, locals had begun dismantling that heritage. I had photos of my first visit and the last visit to compare. Recently I am writing a book on Nagarparkar. I went there for the first time in 1984 and again two years ago. I saw the changes in the lives of the locals and their relationship with their heritage. Sometimes I have to read a lot, just like for my book, The Salt Range & The Pothohar Plateau. I read hundreds of books because the area has a rich history and sites of interest range from ancient Taxila to the Hindu forts of the Salt Range.

AA: How do you see travel writing in Pakistan? Does it will help to promote tourism, given how that sector appears to be a priority of the present government?

SR: Be assured that travel writing is not even considered a genre of writing in Pakistan. Travel writing in newspapers, unfortunately, is only an account of the family vacation to Murree. There is no other professional travel writer. The cost is too high and dividends too low. Only a lunatic would want to be one! We must remember that a travel writer has to be a geographer, historian, anthropologist, sociologist and last of all an autobiographer. Now, to be the first two, one has to read, read, read and read. Pakistanis simply do not read. Their only reading is for exams, not for edification.

The bottom line is that travel writing is dead in Pakistan. Yes, travel writing promotes tourism because it covers more details than a Vlog or recent Youtuber culture in which they often have very little knowledge of the history and geography of a specific place.

I do not see a ray of hope that recent steps by the government would be successful in bringing tourists to Pakistan. For that to work, you will need long-term planning, preservation of our heritage and the establishment of spaces that are friendly to Western tourists. For instance, We are told that they changed the visa policy to bring in more tourists. But look at the list of countries for that softer new visa policy – many of them are places from where we are unlikely to receive many visitors, as their citizens generally don’t even know the name of Pakistan!