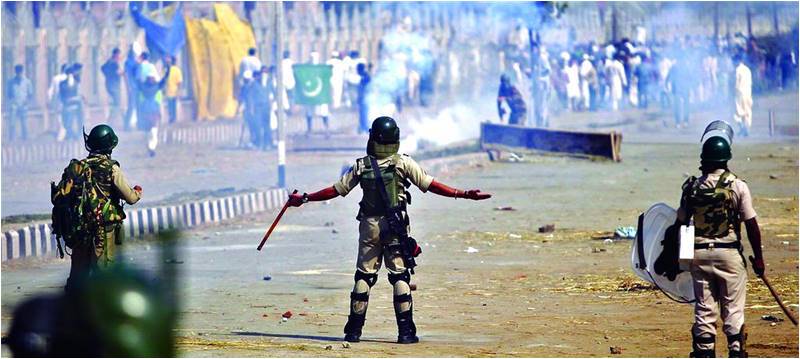

Relations between Pakistan and India are tense over Kashmir. Tensions between these two nuclear-capable countries scare decent human beings in both countries. I was heartened when on August 14, Prime Minister Imran Khan in a nationally televised speech said that he did not believe in wars and that he was a pacifist. I was also heartened when in November 2011, in an interview with CNN-IBN, he said his hatred of India disappeared after he had visited India to play cricket. In an admirable display of candour, he accepted the fact that one grows up hating India due to the bloodshed and violence associated with the Partition. “As time passed, I realised that there’s so much we have in common. We have similar history, there is so much in culture that is so similar compared to Western countries. Above all, there is so much the people of two countries can benefit from if we have a civilised relationship.”

At the time he said that if he came to power, he would do his utmost to improve relations between the two countries. He said he would work for better India-Pakistan relations because he had “received so much love in India.” He also said, “Absolutely, I have no prejudice against any country, and more specifically, India.”

He is not alone. Nearly all Pakistanis grow up hating India, but, unlike Imran Khan, they don’t get an opportunity to unlearn their prejudices. From an early age, Pakistani children are indoctrinated into believing that India is an eternal and cunning enemy because it is dominated by despicable and wily Hindus. Hating India has long been the litmus test of patriotism in Pakistan. The guiding principle of Pakistani historiography is: “Muslims are good guys, Hindus are bad guys.” Pakistani newspapers reinforce this message day in day out.

Here is an example. Nawa-i-Waqt wrote in its issue of February 22, 2004: “Our youngsters take Hindus for human beings because of their appearance. They have no idea that these human-looking creatures are, in fact, bloodthirsty beasts, dreadful crocodiles, dragons and cunning foxes.” The fondest wish of the editor of this newspaper was to be tied to a nuclear missile and get dropped on India (Nawa-i-Waqt, November 5, 2008).

Honestly, I was not so heartened when Imran Khan described Prime Minister Narendra Modi as a racist and fascist leader because of his association with the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). Likening India to Nazi Germany, he called Modi a modern-day Hitler who was determined to subject Indian Muslims to a holocaust. World leaders don’t use such strong language against each other, least of all against a leader who has been elected twice. Fascist leaders are elected only once, if elected at all. Someone might ask him: Didn’t you know his background when you called on him in New Delhi on December 11, 2015? And why on April 9, 2019, during a meeting with senior journalists, did you pin all your hopes on his electoral victory for the resolution of the Kashmir issue? Asadullah Ghalib, a highly patriotic columnist, has written in Nawa-i-Waqt (August 31, 2019) that the anti-RSS narrative will not fly - at least internationally.

In his August 14, 2019 speech, the prime minister spoke highly of the two-nation theory (TNT). On one hand he declared that the RSS ideology was responsible for Gandhi’s murder, on the other he showered praise on Jinnah for pitting Muslims against Gandhi’s ideology of pluralism. On March 30, 1941, Jinnah had described the Congress as a purely Hindu and a fascist organization.

Khan calls himself a student of history. If he had read at least Pathway to Pakistan by Choudhry Khaliquzzaman, a founding father of Pakistan and the first president of the Pakistan Muslim League, he would not have talked in such a facile manner.

Khaliquzzaman writes: “The two-nation theory, which we had used in the fight for Pakistan, had created not only bad blood against the Muslims of the minority provinces, but also an ideological wedge, between them and the Hindus of India.”

He further writes that H.S. Suhrawardy, who later served as Pakistan’s prime minister, doubted the utility of the TNT, which to my mind also had never paid any dividends to us, but after the partition, it proved positively injurious to the Muslims of India. According to him, Jinnah bade farewell to it in his famous speech of August 11, 1947.

However, Sardar Masood Khan, the AJK president, has said that the Kashmiris want to join Pakistan on the basis of the TNT, which is founded on Islam (Dunya, July 10, 2019). Syed Ali Geelani, the most admired Kashmiri leader in Pakistan, has said: “It is as difficult for a Muslim to live in a non-Muslim society as it is for a fish to live in a desert.” He also said: “India has a secular system, which we can under no condition accept” (Outlook, October 28, 2010). This line of reasoning raises the question: If seven million Kashmiri Muslims cannot live in India, what about the 200 million Muslims who live in different parts of India?

Let me draw the attention of readers to some facts, which are not widely known in Pakistan. According to Lt. Col. (r) Sikandar Baloch, the biggest reason for Kashmir’s accession to India was the October 1947 invasion of Kashmir by tribesmen who engaged in indiscriminate loot and plunder (Nawa-i-Waqt, July 24, 2013). Even afterward, Sardar Patel, India’s deputy prime minister, offered to swap Kashmir for non-interference in Hyderabad Deccan, but Pakistan refused. In his memoirs, Sardar Shaukat Hayat, a leader of the Pakistan movement, says that Pakistani Prime Minister Liaqat Ali Khan’s response to this offer was: Am I mad enough to trade a big state like Hyderabad for a few hills of Kashmir? A.G. Noorani, one of the best experts on the Kashmir issue, has written in his magnum opus The Kashmir Dispute 1947-2012: “On November 1, 1947, Lord Mountbatten, India’s governor general, offered Jinnah plebiscite in all the three states: Kashmir, Junagardh, and Hyderabad, but he refused.”

There are many Pakistanis who argue that Modi wants to establish Akhand Bharat (reunited India) by undoing the 1947 partition. They need to be informed of the fact that in an interview with Nai Duniya (August 5, 2012), a Delhi-based weekly Urdu magazine, Modi unequivocally opposed the idea of Akhand Bharat, arguing that it would eventually turn India into a Muslim-majority state. I am happy with India’s current borders, he had said.

M.B. Naqvi, one of the most respected Pakistani journalists, wrote a highly enlightening article for Herald of July 1988. According to him, Pakistan exercised the last option to acquire Kashmir by going to war in 1965. “But while militarily the war was more or less a drawn match, politically it was a disaster. As a consequence of the war, Pakistan finally lost Kashmir.” He advised Pakistan to make friends with India and organize friendly cooperation with it in as many fields as possible. Unfortunately, this sane and sensible advice fell on deaf ears.

Asar Chauhan, a senior columnist, has written that immediately after assuming office as president of Pakistan, Asif Zardari had proposed freezing the Kashmir issue for 30 years (Nawa-i-Waqt, July 24, 2013). However, he couldn’t put this proposal into practice.

I would humbly request the prime minister to steer clear of emotional slogans. He needs to beware of those Kashmiri leaders who are pushing their followers into a head-on collision with the military. The last 30 years have proven that these leaders are not capable of achieving their goals. They have brought the Kashmiris into a dead-end street. They have no realization that militancy has inflicted incalculable harm on the Kashmiris. The hapless Kashmiris deserve better.

The writer is a journalist based in Islamabad and is the author of Handbook of Functional English (Ferozsons)

At the time he said that if he came to power, he would do his utmost to improve relations between the two countries. He said he would work for better India-Pakistan relations because he had “received so much love in India.” He also said, “Absolutely, I have no prejudice against any country, and more specifically, India.”

He is not alone. Nearly all Pakistanis grow up hating India, but, unlike Imran Khan, they don’t get an opportunity to unlearn their prejudices. From an early age, Pakistani children are indoctrinated into believing that India is an eternal and cunning enemy because it is dominated by despicable and wily Hindus. Hating India has long been the litmus test of patriotism in Pakistan. The guiding principle of Pakistani historiography is: “Muslims are good guys, Hindus are bad guys.” Pakistani newspapers reinforce this message day in day out.

In an interview with a Delhi-based weekly Urdu magazine, Modi unequivocally opposed the idea of Akhand Bharat, arguing that it would eventually turn India into a Muslim-majority state

Here is an example. Nawa-i-Waqt wrote in its issue of February 22, 2004: “Our youngsters take Hindus for human beings because of their appearance. They have no idea that these human-looking creatures are, in fact, bloodthirsty beasts, dreadful crocodiles, dragons and cunning foxes.” The fondest wish of the editor of this newspaper was to be tied to a nuclear missile and get dropped on India (Nawa-i-Waqt, November 5, 2008).

Honestly, I was not so heartened when Imran Khan described Prime Minister Narendra Modi as a racist and fascist leader because of his association with the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). Likening India to Nazi Germany, he called Modi a modern-day Hitler who was determined to subject Indian Muslims to a holocaust. World leaders don’t use such strong language against each other, least of all against a leader who has been elected twice. Fascist leaders are elected only once, if elected at all. Someone might ask him: Didn’t you know his background when you called on him in New Delhi on December 11, 2015? And why on April 9, 2019, during a meeting with senior journalists, did you pin all your hopes on his electoral victory for the resolution of the Kashmir issue? Asadullah Ghalib, a highly patriotic columnist, has written in Nawa-i-Waqt (August 31, 2019) that the anti-RSS narrative will not fly - at least internationally.

In his August 14, 2019 speech, the prime minister spoke highly of the two-nation theory (TNT). On one hand he declared that the RSS ideology was responsible for Gandhi’s murder, on the other he showered praise on Jinnah for pitting Muslims against Gandhi’s ideology of pluralism. On March 30, 1941, Jinnah had described the Congress as a purely Hindu and a fascist organization.

Khan calls himself a student of history. If he had read at least Pathway to Pakistan by Choudhry Khaliquzzaman, a founding father of Pakistan and the first president of the Pakistan Muslim League, he would not have talked in such a facile manner.

Khaliquzzaman writes: “The two-nation theory, which we had used in the fight for Pakistan, had created not only bad blood against the Muslims of the minority provinces, but also an ideological wedge, between them and the Hindus of India.”

He further writes that H.S. Suhrawardy, who later served as Pakistan’s prime minister, doubted the utility of the TNT, which to my mind also had never paid any dividends to us, but after the partition, it proved positively injurious to the Muslims of India. According to him, Jinnah bade farewell to it in his famous speech of August 11, 1947.

However, Sardar Masood Khan, the AJK president, has said that the Kashmiris want to join Pakistan on the basis of the TNT, which is founded on Islam (Dunya, July 10, 2019). Syed Ali Geelani, the most admired Kashmiri leader in Pakistan, has said: “It is as difficult for a Muslim to live in a non-Muslim society as it is for a fish to live in a desert.” He also said: “India has a secular system, which we can under no condition accept” (Outlook, October 28, 2010). This line of reasoning raises the question: If seven million Kashmiri Muslims cannot live in India, what about the 200 million Muslims who live in different parts of India?

Let me draw the attention of readers to some facts, which are not widely known in Pakistan. According to Lt. Col. (r) Sikandar Baloch, the biggest reason for Kashmir’s accession to India was the October 1947 invasion of Kashmir by tribesmen who engaged in indiscriminate loot and plunder (Nawa-i-Waqt, July 24, 2013). Even afterward, Sardar Patel, India’s deputy prime minister, offered to swap Kashmir for non-interference in Hyderabad Deccan, but Pakistan refused. In his memoirs, Sardar Shaukat Hayat, a leader of the Pakistan movement, says that Pakistani Prime Minister Liaqat Ali Khan’s response to this offer was: Am I mad enough to trade a big state like Hyderabad for a few hills of Kashmir? A.G. Noorani, one of the best experts on the Kashmir issue, has written in his magnum opus The Kashmir Dispute 1947-2012: “On November 1, 1947, Lord Mountbatten, India’s governor general, offered Jinnah plebiscite in all the three states: Kashmir, Junagardh, and Hyderabad, but he refused.”

There are many Pakistanis who argue that Modi wants to establish Akhand Bharat (reunited India) by undoing the 1947 partition. They need to be informed of the fact that in an interview with Nai Duniya (August 5, 2012), a Delhi-based weekly Urdu magazine, Modi unequivocally opposed the idea of Akhand Bharat, arguing that it would eventually turn India into a Muslim-majority state. I am happy with India’s current borders, he had said.

M.B. Naqvi, one of the most respected Pakistani journalists, wrote a highly enlightening article for Herald of July 1988. According to him, Pakistan exercised the last option to acquire Kashmir by going to war in 1965. “But while militarily the war was more or less a drawn match, politically it was a disaster. As a consequence of the war, Pakistan finally lost Kashmir.” He advised Pakistan to make friends with India and organize friendly cooperation with it in as many fields as possible. Unfortunately, this sane and sensible advice fell on deaf ears.

Asar Chauhan, a senior columnist, has written that immediately after assuming office as president of Pakistan, Asif Zardari had proposed freezing the Kashmir issue for 30 years (Nawa-i-Waqt, July 24, 2013). However, he couldn’t put this proposal into practice.

I would humbly request the prime minister to steer clear of emotional slogans. He needs to beware of those Kashmiri leaders who are pushing their followers into a head-on collision with the military. The last 30 years have proven that these leaders are not capable of achieving their goals. They have brought the Kashmiris into a dead-end street. They have no realization that militancy has inflicted incalculable harm on the Kashmiris. The hapless Kashmiris deserve better.

The writer is a journalist based in Islamabad and is the author of Handbook of Functional English (Ferozsons)