plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose

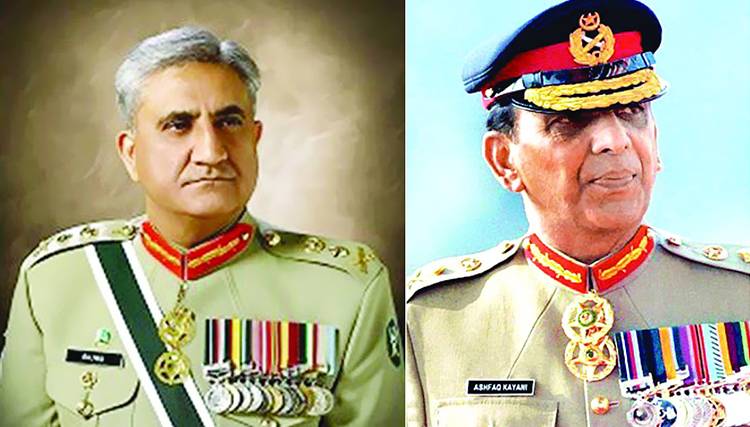

There are two ways of approaching the full-term extension granted to General Ashfaq Parvez Kayani (sorry, General Qamar Javed Bajwa) by the current Pakistan Peoples Party government (correction, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf government) — the democratic practice, which may also be deemed abstract in this republic; and the real, which may be termed contextual. Conclusions will differ, depending on the approach taken. Let’s consider both in that order.

The democratic approach, which is also ironically the ideal approach in this republic, would challenge Kayani’s (read: Bajwa’s) extension. It can do so by appealing to the concept of civilian supremacy which stipulates that the civilian principals must enjoy effective control over the military, this decision being clearly violative of that principle. Everyone knows where the decision was taken and why it was stamped by Prime Minister Yousaf Raza Gilani (err, Prime Minister Imran Khan).

The ideal can also appeal to the organisational framework and dismiss the gloss that is being put on the concept of continuity of command and the security situation in the region. Continuity of command is an institutional function, not a device to keep individuals in cushy jobs. Early into Muslim conquests the second Caliph, Umar ibn-e-Khattab, removed Khalid bin Walid, decidedly the best and the most successful general commanding the Muslim armies and made him fight under Abu Ubaidah as an ordinary commander. This, when Muslim forces had won many impressive battles under bin Walid’s command, first against the Sassanids and then against the armies of the Eastern Roman Empire.

What did bin Walid do? He did as directed by the political authority.

It is deeply ironic that so many Muslim-majority countries have grappled with lopsided civil-military relations despite a clear example from the early history of Islam about political supremacy over military leadership.

There is another, obvious problem with arguing the concept of continuity thus. It implies that other generals in the army, in line to be promoted, are lacking in professionalism or the understanding of higher strategy or, worse, both.

One doesn’t need to belabour the point to demonstrate how poorly that assumption reflects on the army and the processes that produce its high command. As a student of military strategy and a long-time observer of the Pakistani army, I would be the first to reject such a conclusion. But precisely for this reason it is difficult for any objective analyst to swallow the implication that sans Bajwa the army and, by extension, the country will be unable to formulate and implement a strategic response to the current challenges it faces.

My reservations are, of course, notwithstanding the guidance emanating from the nightly TV circus that has come to define the lies we live as a people.

But, in the end, it reflects on the man who leads the country, the chief executive, the prime minister.

In his Supreme Command: Soldiers, Statesmen, and Leadership in Wartime, Eliot Cohen looked at four political leaders, Abraham Lincoln, Georges Clemenceau, Winston Churchill, and David Ben-Gurion, and argued that statesmen not only make excellent wartime leaders, they prod and provoke and effectively control their military leaders, pushing their “military subordinates to succeed where they might have failed if left to their own devices.” In other words, Cohen challenges through these case studies the orthodox belief that during wars “politicians should declare a military operation’s objectives and then step aside and leave the business of war to the military.”

To this end, among other evidence, Cohen reproduces a letter Lincoln wrote to Major-General Joseph Hooker on January 26, 1863 after he (Lincoln) had placed Hooker at the head of the Army of the Potomac: “I have heard, in such way as to believe it, of your recently saying that both the Army and the Government needed a Dictator. Of course it was not for this, but in spite of it, that I have given you the command. Only those generals who gain successes, can set up dictators. What I now ask of you is military success, and I will risk the dictatorship …. And now, beware of rashness. Beware of rashness, but with energy, and sleepless vigilance, go forward, and give us victories.”

Incidentally, Lincoln, over the course of the American Civil War taught himself the nuances of military-operational strategy and was generally known to have a better grasp of the battlefield than many of his commanders.

But then there’s the reality of Pakistan, the picture in the cellar that continues to decay even as Dorian Gray appears to retain his youth and his good looks. Upstairs we have all the trappings of a federal, constitutional, democratic system; the cellar is another story. One could also call it the musty underbelly of Pakistan’s power configuration.

Let me let the reader in on a fact: the two opening paragraphs of this article were written in July 2010. It was distressingly easy to change the PPP government to the PTI government and Yousaf Raza Gillani to Imran Khan. What does that indicate apart from what’s obvious, that the newness of this dispensation has the sameness and staleness of the old? Does one even need to make an argument to answer that question? I don’t think so. But one thing is certain: we definitely like to do the same thing over and over while expecting different results.

Stupidity or naiveté?

Neither, we are told. Live a lie as we do, it’s called grand strategy; maybe even national interest and its reification. As the letter from the PMO indicates, our best response to the challenges we face is to ignore institutional capacity in favour of individuals, preferring, to quote Jack Gilbert, “the month’s rapture” to “the normal excellence, of long accomplishment”, exception to the dull but robust routine, the abnormal to what is steady and clear.

So help us Darwin.

The writer is a former News Editor of The Friday Times. He reluctantly tweets @ejazhaider

There are two ways of approaching the full-term extension granted to General Ashfaq Parvez Kayani (sorry, General Qamar Javed Bajwa) by the current Pakistan Peoples Party government (correction, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf government) — the democratic practice, which may also be deemed abstract in this republic; and the real, which may be termed contextual. Conclusions will differ, depending on the approach taken. Let’s consider both in that order.

The democratic approach, which is also ironically the ideal approach in this republic, would challenge Kayani’s (read: Bajwa’s) extension. It can do so by appealing to the concept of civilian supremacy which stipulates that the civilian principals must enjoy effective control over the military, this decision being clearly violative of that principle. Everyone knows where the decision was taken and why it was stamped by Prime Minister Yousaf Raza Gilani (err, Prime Minister Imran Khan).

The ideal can also appeal to the organisational framework and dismiss the gloss that is being put on the concept of continuity of command and the security situation in the region. Continuity of command is an institutional function, not a device to keep individuals in cushy jobs. Early into Muslim conquests the second Caliph, Umar ibn-e-Khattab, removed Khalid bin Walid, decidedly the best and the most successful general commanding the Muslim armies and made him fight under Abu Ubaidah as an ordinary commander. This, when Muslim forces had won many impressive battles under bin Walid’s command, first against the Sassanids and then against the armies of the Eastern Roman Empire.

What did bin Walid do? He did as directed by the political authority.

It is deeply ironic that so many Muslim-majority countries have grappled with lopsided civil-military relations despite a clear example from the early history of Islam about political supremacy over military leadership.

There is another, obvious problem with arguing the concept of continuity thus. It implies that other generals in the army, in line to be promoted, are lacking in professionalism or the understanding of higher strategy or, worse, both.

It is deeply ironic that so many Muslim-majority countries have grappled with lopsided civil-military relations despite a clear example from the early history of Islam about political supremacy over military leadership

One doesn’t need to belabour the point to demonstrate how poorly that assumption reflects on the army and the processes that produce its high command. As a student of military strategy and a long-time observer of the Pakistani army, I would be the first to reject such a conclusion. But precisely for this reason it is difficult for any objective analyst to swallow the implication that sans Bajwa the army and, by extension, the country will be unable to formulate and implement a strategic response to the current challenges it faces.

My reservations are, of course, notwithstanding the guidance emanating from the nightly TV circus that has come to define the lies we live as a people.

But, in the end, it reflects on the man who leads the country, the chief executive, the prime minister.

In his Supreme Command: Soldiers, Statesmen, and Leadership in Wartime, Eliot Cohen looked at four political leaders, Abraham Lincoln, Georges Clemenceau, Winston Churchill, and David Ben-Gurion, and argued that statesmen not only make excellent wartime leaders, they prod and provoke and effectively control their military leaders, pushing their “military subordinates to succeed where they might have failed if left to their own devices.” In other words, Cohen challenges through these case studies the orthodox belief that during wars “politicians should declare a military operation’s objectives and then step aside and leave the business of war to the military.”

To this end, among other evidence, Cohen reproduces a letter Lincoln wrote to Major-General Joseph Hooker on January 26, 1863 after he (Lincoln) had placed Hooker at the head of the Army of the Potomac: “I have heard, in such way as to believe it, of your recently saying that both the Army and the Government needed a Dictator. Of course it was not for this, but in spite of it, that I have given you the command. Only those generals who gain successes, can set up dictators. What I now ask of you is military success, and I will risk the dictatorship …. And now, beware of rashness. Beware of rashness, but with energy, and sleepless vigilance, go forward, and give us victories.”

Incidentally, Lincoln, over the course of the American Civil War taught himself the nuances of military-operational strategy and was generally known to have a better grasp of the battlefield than many of his commanders.

But then there’s the reality of Pakistan, the picture in the cellar that continues to decay even as Dorian Gray appears to retain his youth and his good looks. Upstairs we have all the trappings of a federal, constitutional, democratic system; the cellar is another story. One could also call it the musty underbelly of Pakistan’s power configuration.

Let me let the reader in on a fact: the two opening paragraphs of this article were written in July 2010. It was distressingly easy to change the PPP government to the PTI government and Yousaf Raza Gillani to Imran Khan. What does that indicate apart from what’s obvious, that the newness of this dispensation has the sameness and staleness of the old? Does one even need to make an argument to answer that question? I don’t think so. But one thing is certain: we definitely like to do the same thing over and over while expecting different results.

Stupidity or naiveté?

Neither, we are told. Live a lie as we do, it’s called grand strategy; maybe even national interest and its reification. As the letter from the PMO indicates, our best response to the challenges we face is to ignore institutional capacity in favour of individuals, preferring, to quote Jack Gilbert, “the month’s rapture” to “the normal excellence, of long accomplishment”, exception to the dull but robust routine, the abnormal to what is steady and clear.

So help us Darwin.

The writer is a former News Editor of The Friday Times. He reluctantly tweets @ejazhaider