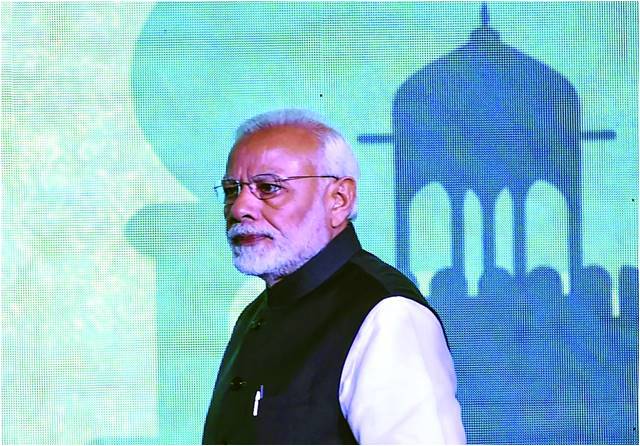

The revocation of the special status of Indian-administered Kashmir by Prime Minister Modi’s government came as a surprise to many. Yet this should not have been the case. If people had followed developments during Modi’s first stint in office, this act would have seemed well in tune with his proclivity towards showmanship and presenting himself as a strongman in the eyes of the Indian public. Within a day, more than 70 years of Indian promises to the Kashmiris were grounded to dust by a man whose ambition knows no bounds.

But behind Modi’s and BJP’s belligerence, there are some statistics that provided him the grounds for carrying out this act. Economics is a major part of this story, and as I will explain in the following paragraphs, it is economics that will ultimately tilt the balance in favour of either success or failure of this move.

Let’s first decode the question of timing. Why now? Why not earlier, during the first stint? It will be a shortcoming on part of the imagination of those who believe that the idea to annex Kashmir this way must have been born now. The idea must have been there from the very beginning. He just didn’t have the numbers earlier. That has completely changed now, after BJP’s crushing election victory. The earlier constraint of being shorn of numbers suddenly vanished, and the time came to put some long-held ideas into motion.

The big question: will the gambit succeed? A lot of commentators have already written profusely about the issue. But their arguments mainly swirl around emotions and political assessments. Missing from the picture is the important aspect of the economic muscle to sustain such initiatives. My own impression is that it is here that this gambit will either end up as a colossal botch-up or as a success. Let us see what the ground realities communicate to us.

We start with realising that as far as the international community is concerned, India is a giant and Pakistan a mere midget. There are not many countries in the world (in fact any country) that would take the risk of breaking up their economic rapport with India, one of the world’s largest consumer market. It is thus apparent that there would be no adverse external shock to the Indian economy. Thus, India has little to worry about this facet.

This aspect becomes amply clear when we see the reaction of the Saudi Arabia and China. A few days after Modi’s government made its move, Saudi Arabia (our ‘Islamic brother’) announced investment to the tune of $55 billion in India’s petrochemical sector alone. This is perhaps what prompted a red-faced Pakistani foreign minister, Mr Qureshi, to complain bitterly that Islamic countries have their commercial interests! It was childish clamour, to say the least. A man as experienced as Qureshi should have by now grasped the undeniable reality that a nation’s commercial and economic interests reign supreme in the modern world. Similarly, China (our ‘Iron’ brother) has yet to take any adverse economic or financial action against India, despite complaining that it has illegally usurped part of Laddakh claimed by China.

The muted international response to this move is rooted in India’s might as an economic giant of the global economy, with whom the global community has much to look forward to in terms of business opportunities. In contrast, what has Pakistan got to offer? Chicken and eggs, or an illusory story of success built upon CPEC? Sorry, nobody is buying this stuff.

Being shielded from an adverse external economic shock does not, however, mean that India can relax and wait for calm and normalcy to return to the region. I believe it is internal economic factors that will be the most critical part of this story in the years to come. Let me venture forth to briefly explain.

In the first stint of the Modi government, the economic planners initiated a spectacular surprise in the form of the ‘demonetization’ exercise. Within a day, 86 percent of the total currency in circulation was outlawed under the pretext of curbing illegal (or black money) and documenting the informal economy. The end result was a long, endless que of lines and a severe cash crunch that left many businesses on the edge of solvency. Many years down the line, India’s leading economist might consider that experiment as largely a waste of time and resources. Corruption is still rampant, black money still flows around in the Indian economy and the informal sector is still active. In the process, India lost at least two percent of its GDP. Here, Modi’s brinksmanship stuttered and failed.

Why is this story important in the context of our discussion? Like the demonetization exercise, Modi is under the false assumption that he can pull off another economic coup. After all, India’s large economic size, its continued economic expansion at a healthy pace and the world’s confidence in its workings will ensure that the finances of India will remain healthy. A certain percentage of additional financial resources will be diverted to Kashmir, where additional expenditures would generate economic activity, in turn creating more jobs. In the long run, the simmering tensions and hate would dissipate as healthy economic growth puts a damper on the struggle of Kashmiris.

Unfortunately, this narrative is built upon many assumptions that may not hold. For a start, India’s economic growth numbers (especially under the Modi government) have increasingly come to be questioned by leading figures of the field. Second, major initiatives like revoking Article 370 are not costless affairs. Imagine the additional resources that are being, and will be in the future, devoted to justify this action. Although there are no exact figures available, the costs of such measures run into billions per day. Will India will be able to sustain this well into the future? There is no guarantee it can.

Also imagine the ‘spill overs’ of this action. There are many active insurgencies running within India. Fearing the same fate to befall them as it did to Kashmiris, their struggle against India may pick up pace. Tackling them would require devoting even more resources. Plus, there is no guarantee that additional expenses will substantially increase economic activity. When people of a place are not willing to do business with you, millions or billions of rupees would hardly garner any sympathies. It is just guess work without any solid bases.

Just imagine what would happen if additional regions of India are up in arms and the insurgency spreads. Such a state of affairs does not elicit confidence in a country, and investors may start repatriating their investments. Plus, the world will then have second thoughts on firmly backing India. If the growth in revenues cannot keep up pace with additional expenses, things would start deteriorating gradually. Also note that India’s corporate sector’s profits are not as healthy as they used to be.

This debate can be continued at length. But the above stated lines should be enough to clarify where the fault lines lie. It is internal economic dynamics rather than a foreign financial shock that will ultimately decide the veracity and wisdom of the move to revoke Article 370. My hunch is that India’s ambitions under Modi are a bit misplaced, and this decision will weigh down heavily upon Indian economic and political future.

The writer is an economist

But behind Modi’s and BJP’s belligerence, there are some statistics that provided him the grounds for carrying out this act. Economics is a major part of this story, and as I will explain in the following paragraphs, it is economics that will ultimately tilt the balance in favour of either success or failure of this move.

Let’s first decode the question of timing. Why now? Why not earlier, during the first stint? It will be a shortcoming on part of the imagination of those who believe that the idea to annex Kashmir this way must have been born now. The idea must have been there from the very beginning. He just didn’t have the numbers earlier. That has completely changed now, after BJP’s crushing election victory. The earlier constraint of being shorn of numbers suddenly vanished, and the time came to put some long-held ideas into motion.

The muted international response to this move is rooted in India’s might as an economic giant of the global economy, with whom the global community has much to look forward to in terms of business opportunities. In contrast, what has Pakistan got to offer?

The big question: will the gambit succeed? A lot of commentators have already written profusely about the issue. But their arguments mainly swirl around emotions and political assessments. Missing from the picture is the important aspect of the economic muscle to sustain such initiatives. My own impression is that it is here that this gambit will either end up as a colossal botch-up or as a success. Let us see what the ground realities communicate to us.

We start with realising that as far as the international community is concerned, India is a giant and Pakistan a mere midget. There are not many countries in the world (in fact any country) that would take the risk of breaking up their economic rapport with India, one of the world’s largest consumer market. It is thus apparent that there would be no adverse external shock to the Indian economy. Thus, India has little to worry about this facet.

This aspect becomes amply clear when we see the reaction of the Saudi Arabia and China. A few days after Modi’s government made its move, Saudi Arabia (our ‘Islamic brother’) announced investment to the tune of $55 billion in India’s petrochemical sector alone. This is perhaps what prompted a red-faced Pakistani foreign minister, Mr Qureshi, to complain bitterly that Islamic countries have their commercial interests! It was childish clamour, to say the least. A man as experienced as Qureshi should have by now grasped the undeniable reality that a nation’s commercial and economic interests reign supreme in the modern world. Similarly, China (our ‘Iron’ brother) has yet to take any adverse economic or financial action against India, despite complaining that it has illegally usurped part of Laddakh claimed by China.

The muted international response to this move is rooted in India’s might as an economic giant of the global economy, with whom the global community has much to look forward to in terms of business opportunities. In contrast, what has Pakistan got to offer? Chicken and eggs, or an illusory story of success built upon CPEC? Sorry, nobody is buying this stuff.

Being shielded from an adverse external economic shock does not, however, mean that India can relax and wait for calm and normalcy to return to the region. I believe it is internal economic factors that will be the most critical part of this story in the years to come. Let me venture forth to briefly explain.

In the first stint of the Modi government, the economic planners initiated a spectacular surprise in the form of the ‘demonetization’ exercise. Within a day, 86 percent of the total currency in circulation was outlawed under the pretext of curbing illegal (or black money) and documenting the informal economy. The end result was a long, endless que of lines and a severe cash crunch that left many businesses on the edge of solvency. Many years down the line, India’s leading economist might consider that experiment as largely a waste of time and resources. Corruption is still rampant, black money still flows around in the Indian economy and the informal sector is still active. In the process, India lost at least two percent of its GDP. Here, Modi’s brinksmanship stuttered and failed.

Why is this story important in the context of our discussion? Like the demonetization exercise, Modi is under the false assumption that he can pull off another economic coup. After all, India’s large economic size, its continued economic expansion at a healthy pace and the world’s confidence in its workings will ensure that the finances of India will remain healthy. A certain percentage of additional financial resources will be diverted to Kashmir, where additional expenditures would generate economic activity, in turn creating more jobs. In the long run, the simmering tensions and hate would dissipate as healthy economic growth puts a damper on the struggle of Kashmiris.

Unfortunately, this narrative is built upon many assumptions that may not hold. For a start, India’s economic growth numbers (especially under the Modi government) have increasingly come to be questioned by leading figures of the field. Second, major initiatives like revoking Article 370 are not costless affairs. Imagine the additional resources that are being, and will be in the future, devoted to justify this action. Although there are no exact figures available, the costs of such measures run into billions per day. Will India will be able to sustain this well into the future? There is no guarantee it can.

Also imagine the ‘spill overs’ of this action. There are many active insurgencies running within India. Fearing the same fate to befall them as it did to Kashmiris, their struggle against India may pick up pace. Tackling them would require devoting even more resources. Plus, there is no guarantee that additional expenses will substantially increase economic activity. When people of a place are not willing to do business with you, millions or billions of rupees would hardly garner any sympathies. It is just guess work without any solid bases.

Just imagine what would happen if additional regions of India are up in arms and the insurgency spreads. Such a state of affairs does not elicit confidence in a country, and investors may start repatriating their investments. Plus, the world will then have second thoughts on firmly backing India. If the growth in revenues cannot keep up pace with additional expenses, things would start deteriorating gradually. Also note that India’s corporate sector’s profits are not as healthy as they used to be.

This debate can be continued at length. But the above stated lines should be enough to clarify where the fault lines lie. It is internal economic dynamics rather than a foreign financial shock that will ultimately decide the veracity and wisdom of the move to revoke Article 370. My hunch is that India’s ambitions under Modi are a bit misplaced, and this decision will weigh down heavily upon Indian economic and political future.

The writer is an economist