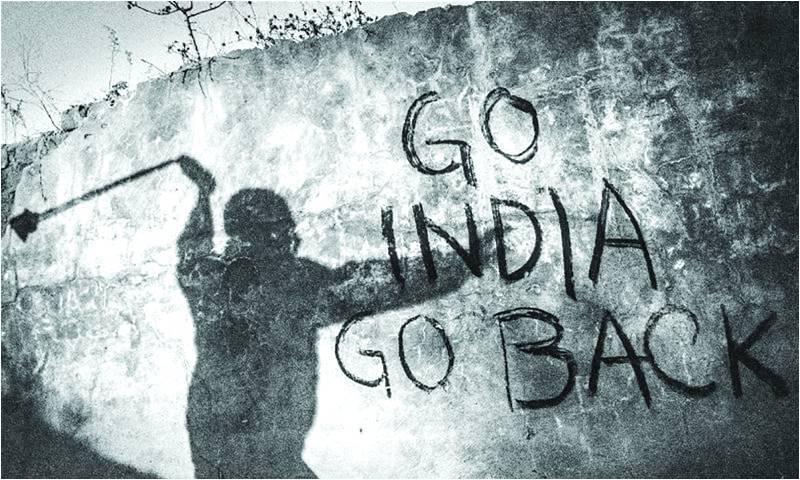

This is about Kashmir, the occupied land that has now been carved and annexed. But no, this is not about the shysters in Narendra Modi’s RSS-government who raided articles 3 and 367 of the Indian Constitution to hollow out article 370, the Constitutional fig leaf India had used to retain its illegal and tenuous relationship with Occupied Jammu and Kashmir, which included the Ladakh division.

Those are issues for the jurists to discuss, though they are tremendously significant and the fight on that front must be taken up by those in India who still believe in constitutionalism, and most likely it will be. Eminent India lawyer, A G Noorani’s definitive 2011 work, Article 370: A Constitutional History of Jammu and Kashmir should help the Supreme Court of India to figure out the constitutional deceit effected by the Modi government against the peoples of Indian-Occupied Kashmir and the Indian constitution. So, yes, that fight has its own terrible substance and momentousness and one will have to see whether the Indian SC acts independently or does unto 370 what it did to Afzal Guru in keeping with the sentiments of the Indian public.

But there’s more to this sordid episode than mere legalities. And I say this after having listened to the 40-minute speech by Mr Modi, an address to the Indians, his Hindutva constituency, but also the Kashmiris who have been under the worst-possible communication blackout in the run-up to the serpentine move to revoke article 370.

Modi gave a long list of ‘exceptions’ guided by art. 370 that had deepened the sense of separation among the Kashmiris and held development back in that Occupied state. He then went on to list what all his government planned to do for Kashmir’s uplift, now that it, the Union government, was directly responsible for running the affairs of Kashmir. His address was faux-largesse wrapped in noblesse oblige and, in a moment whose irony should not be lost on anyone, the Indian liberal’s civiliser project, Pankaj Mishra’s term, was peddled by the most successful icon of rightwing Hindutva creed.

It reminded me of the dialogue between Mustapha Mond and John the Savage in Huxley’s Brave New World.

“But I like the inconveniences.”

“We don’t,” said the Controller. “We prefer to do things comfortably.”

“But I don’t want comfort. I want God, I want poetry, I want real danger, I want freedom, I want goodness. I want sin.”

“In fact,” said Mustapha Mond, “you’re claiming the right to be unhappy.”

“All right then,” said the Savage defiantly, “I’m claiming the right to be unhappy.”

“Not to mention the right to grow old and ugly and impotent; the right to have syphilis and cancer; the right to have too little to eat; the right to be lousy; the right to live in constant apprehension of what may happen tomorrow; the right to catch typhoid; the right to be tortured by unspeakable pains of every kind.” There was a long silence.

“I claim them all,” said the Savage at last.

In a 2008 interview to Los Angeles Review of Books, Mishra said, of his own experience of reporting from Occupied Kashmir: “…India had a civilizing mission: it had to show Kashmir’s overwhelmingly religious Muslims the light of secular reason — by force, if necessary. The brutal realities of India’s military occupation of Kashmir and the blatant falsehoods and deceptions that accompanied it forced me to revisit many of the old critiques of Western imperialism and its rhetoric of progress.”

In October 2004, when I travelled to Jammu and then the Valley, part of a first-ever delegation of journalists from Pakistan, I was struck by the presence of Indian occupation forces. There was army of course and there was police but then there were elements of almost every paramilitary force in India’s coercive apparatus operating in the area. The Valley was the worst, even as I can never forget the moment when, after crossing the Banihal tunnel, I got my first view of the Vale. It was breathtaking; equally breathtaking and disconcerting was the menacing atmosphere of fear that pervaded the place. So palpable was it that one could cut through it with a knife.

Years ago, in a rare essay in The Guardian on how he dealt with his art, essentially writing plays, Harold Pinter cautioned the reader against “the writer who puts forward his concern for you to embrace, who leaves you in no doubt of his worthiness, his usefulness, his altruism, who declares that his heart is in the right place, and ensures that it can be seen in full view, a pulsating mass where his characters ought to be.” Because, Pinter continued, “What is presented, so much of the time, as a body of active and positive thought is in fact a body lost in a prison of empty definition and cliche.”

He could have been talking about Modi’s August 8 address: what was presented as a body of active and positive thought was a body lost in a prison of empty definition and cliche. Not just that, but in this case, a play penned by deceit itself.

All the more cliched because nothing he said about bringing development to Kashmir is what hasn’t been said before — or tried before. His economic package could have been any of the many such packages given by New Delhi to Occupid Kashmir. But those bribes didn’t work then and they won’t work now. Man’s life, as John the Savage was at pains to tell Mustapha Mond, is not about comforts, the golden cage. It’s about self-realisation, self-actualisation, the freedom to be, the freedom to make choices, good or bad, the knowledge that one is not living with darkness at noon.

Article 370 didn’t hamper Kashmir’s development. India’s imperial project did, a hegemonic undertaking repeatedly rejected by the Kashmiris, so thoroughly in fact that India has to arrest, torture, blind, maim and kill the Kashmiris constantly to get them in line — unsuccessfully.

The fight has only entered the next phase, possibly far more oppressive than anything previously seen.

The writer is a journalist based in Lahore and previously worked at TFT. His elders fought the Dogra army during the Poonch Uprising. He tweets @ejazhaider reluctantly

Those are issues for the jurists to discuss, though they are tremendously significant and the fight on that front must be taken up by those in India who still believe in constitutionalism, and most likely it will be. Eminent India lawyer, A G Noorani’s definitive 2011 work, Article 370: A Constitutional History of Jammu and Kashmir should help the Supreme Court of India to figure out the constitutional deceit effected by the Modi government against the peoples of Indian-Occupied Kashmir and the Indian constitution. So, yes, that fight has its own terrible substance and momentousness and one will have to see whether the Indian SC acts independently or does unto 370 what it did to Afzal Guru in keeping with the sentiments of the Indian public.

But there’s more to this sordid episode than mere legalities. And I say this after having listened to the 40-minute speech by Mr Modi, an address to the Indians, his Hindutva constituency, but also the Kashmiris who have been under the worst-possible communication blackout in the run-up to the serpentine move to revoke article 370.

Modi gave a long list of ‘exceptions’ guided by art. 370 that had deepened the sense of separation among the Kashmiris and held development back in that Occupied state. He then went on to list what all his government planned to do for Kashmir’s uplift, now that it, the Union government, was directly responsible for running the affairs of Kashmir. His address was faux-largesse wrapped in noblesse oblige and, in a moment whose irony should not be lost on anyone, the Indian liberal’s civiliser project, Pankaj Mishra’s term, was peddled by the most successful icon of rightwing Hindutva creed.

Modi gave a long list of ‘exceptions’ guided by art. 370 that had deepened the sense of separation among the Kashmiris and held development back in that Occupied state

It reminded me of the dialogue between Mustapha Mond and John the Savage in Huxley’s Brave New World.

“But I like the inconveniences.”

“We don’t,” said the Controller. “We prefer to do things comfortably.”

“But I don’t want comfort. I want God, I want poetry, I want real danger, I want freedom, I want goodness. I want sin.”

“In fact,” said Mustapha Mond, “you’re claiming the right to be unhappy.”

“All right then,” said the Savage defiantly, “I’m claiming the right to be unhappy.”

“Not to mention the right to grow old and ugly and impotent; the right to have syphilis and cancer; the right to have too little to eat; the right to be lousy; the right to live in constant apprehension of what may happen tomorrow; the right to catch typhoid; the right to be tortured by unspeakable pains of every kind.” There was a long silence.

“I claim them all,” said the Savage at last.

In a 2008 interview to Los Angeles Review of Books, Mishra said, of his own experience of reporting from Occupied Kashmir: “…India had a civilizing mission: it had to show Kashmir’s overwhelmingly religious Muslims the light of secular reason — by force, if necessary. The brutal realities of India’s military occupation of Kashmir and the blatant falsehoods and deceptions that accompanied it forced me to revisit many of the old critiques of Western imperialism and its rhetoric of progress.”

In October 2004, when I travelled to Jammu and then the Valley, part of a first-ever delegation of journalists from Pakistan, I was struck by the presence of Indian occupation forces. There was army of course and there was police but then there were elements of almost every paramilitary force in India’s coercive apparatus operating in the area. The Valley was the worst, even as I can never forget the moment when, after crossing the Banihal tunnel, I got my first view of the Vale. It was breathtaking; equally breathtaking and disconcerting was the menacing atmosphere of fear that pervaded the place. So palpable was it that one could cut through it with a knife.

Years ago, in a rare essay in The Guardian on how he dealt with his art, essentially writing plays, Harold Pinter cautioned the reader against “the writer who puts forward his concern for you to embrace, who leaves you in no doubt of his worthiness, his usefulness, his altruism, who declares that his heart is in the right place, and ensures that it can be seen in full view, a pulsating mass where his characters ought to be.” Because, Pinter continued, “What is presented, so much of the time, as a body of active and positive thought is in fact a body lost in a prison of empty definition and cliche.”

He could have been talking about Modi’s August 8 address: what was presented as a body of active and positive thought was a body lost in a prison of empty definition and cliche. Not just that, but in this case, a play penned by deceit itself.

All the more cliched because nothing he said about bringing development to Kashmir is what hasn’t been said before — or tried before. His economic package could have been any of the many such packages given by New Delhi to Occupid Kashmir. But those bribes didn’t work then and they won’t work now. Man’s life, as John the Savage was at pains to tell Mustapha Mond, is not about comforts, the golden cage. It’s about self-realisation, self-actualisation, the freedom to be, the freedom to make choices, good or bad, the knowledge that one is not living with darkness at noon.

Article 370 didn’t hamper Kashmir’s development. India’s imperial project did, a hegemonic undertaking repeatedly rejected by the Kashmiris, so thoroughly in fact that India has to arrest, torture, blind, maim and kill the Kashmiris constantly to get them in line — unsuccessfully.

The fight has only entered the next phase, possibly far more oppressive than anything previously seen.

The writer is a journalist based in Lahore and previously worked at TFT. His elders fought the Dogra army during the Poonch Uprising. He tweets @ejazhaider reluctantly