I hesitated a bit before knocking at the rickety old door. After all, it had been more than 20 years since I had last visited this house. I was visiting the old neighbourhood where I was born and raised in the Walled City of Peshawar. I could not resist the visit when I saw the nondescript two-story house with the faded wooden front door.

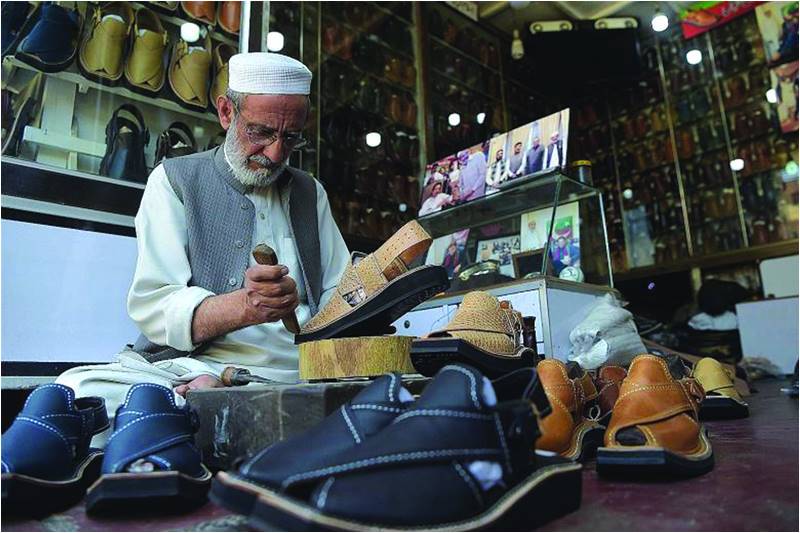

The door opened with the same creak that it had for all those years. As if frozen in time, there squatted Jumma Khan, the shoemaker, in the tiny foyer at the base of the steps, busy making the boat-shaped native shoes called khussas.

I stepped into the tiny foyer illuminated by a few oblique rays of sunlight ricocheting in from the narrow street outside. He recognized me and stood up, dropping a few tools on the floor in the process.

“It is so good to see you, little Agha Ji”, he said enthusiastically as he embraced me in a strong, affectionate hug.“My God, it has been at least 20 winters since I last saw you! When did you come back from vilayat (foreign land)? How is your wife— oh excuse me, your Mem Sahib and how many children do you have?” I could hardly keep up with his rapid-fire questions.

We were suddenly interrupted by his wife, who suspecting some activity downstairs, could not resist getting involved. “O father of Qayum,” she called from top of the stairs, ”Who is visting?”

Apa Najab, the strong-willed, slave-driving, life-long wife of Jumma Khan, still reigned in that house. Jumma Khan, always the obedient husband, answered in excitement, “It is little Agha Ji, Amjood, who lives in vilayat.” He never could pronounce my name properly.

Apa Najab came running down the stairs, and before she could grab my head to plant a kiss and say a thousand prayers for me and my family, she corrected her husband, “Don’t call him little Amjood anymore. He is Doctor Sahib!”

We sat down, I on the little stool and Apa Najab on the bottom step. Jumma Khan took his seat on the low cushioned stool and we began reminiscing.

“How are the kids?”, I inquired.

Before Jumma Khan had a chance to open his mouth, Apa Najab chimed in, “Yusaf is a clerk at the bank, is married, and has two children”.

“How about Qayum”?

There was a brief silence. I didn’t have to wait for the answer, but she answered anyway. “He is still possessed by bad spirits. You remember one time, a long time ago, when he had taken to fits? Well, he still has those fits”. As if to change from a painful subject, she resumed talking about the good old times.

Qayum had been my grade-school classmate. He always hung around older boys, and rumour had it that he was gay. In order to cover for his late-evening activities, he claimed to have been possessed by spirits who wouldn’t let him come home on time. Apa Najab and Jumma Khan probably knew the real reason, but couldn’t do much about it. They consulted the mosque mullah and other holy men, but Qayum continued on his jolly way.

I had heard he still passed his time at the city park, loafing around. Society had provided a respectable cover: “possession by spirits”. It permitted him to indulge in activities that could not otherwise be condoned.

Jumma Khan interrupted the conversation to ask if I would like a cup of green tea. I said I would. He headed for the door to order a pot from the corner teashop. But Apa Najab, ever the mother hen, stopped him.

“You don’t order tea from the outside for a guest like our doctor Sahib. I will make some green tea myself.”

Now, it was not often that Apa Najab would whip up some tea for a visitor. Special visitors were the exception. For occasional visitors and friends, tea was customarily ordered from the tea shop at the street corner.

“Whatever happened to the people who lived across the street from you? I inquired.

“Oh, you mean Salam and Omar, the cap-makers?”

“Yes”

“Well, they are still here. They live in the same house. The brothers get along fine, but their wives don’t.”

“And what about Dr. Qureshi?”

“God bless his soul, he passed away two years ago. He was good to us. But his children are nothing like their father. His middle son runs the clinic, but he has neither his father’s knowledge nor the old man’s sense of charity. Their whole family is ruined.”

Dr. Qureshi was an interesting figure in the neighbourhood. Trained as a male hospital attendant, he spent quite a bit of time in the Middle East. Due to the lack of trained personnel in those countries in the 1940s and 1950s, he was put in charge of a small hospital. Years later he returned to Peshawar and opened a clinic on our street. With his meticulously manicured Van Dyke beard and a three-piece suit, he looked too elegant and too European to be a part of our neighbourhood. But, as Jumma Khan mentioned, he was kind and compassionate and never failed to tend to a sick person.

“And you remember Jalil Ghazi.” Jumma Khan was certainly savouring his excursion into the past. “He also died two summers ago. You remember how he used to hop all over town on one leg? Well, his joints gave up on him and he died a miserable death, confined to his bed. There were times when he hardly spent any time in his bachelor room, and then there were times when he couldn’t move without help. May Allah forgive all of us”.

Jalil Ghazi was a colourful personality. A confirmed bachelor, he lost one leg on a fateful day in April 1930. Never a brave man, Jalil found himself part of a political rally in Qissa Khwani Bazaar. An English police officer ordered the procession to stop. Instead he was pelted with rocks and bricks, severely injuring him. When verbal warnings failed to halt the advancing surge, the police opened fire. As a result hundreds of unarmed civilians died. Jalil was hit in the leg and it had to be amputated. Instantly the bullet wound made him a living legend. Thereafter he was to be found, on crutches, at the head of every gathering, whether it was a political rally, a neighbourhood funeral or a wedding.

At this time Apa Najab came down the stairs with a tray of green tea, saltine biscuits and sweets. The ingenious woman had apparently sent a neighbour’s boy to fetch the edibles from the bazaar, borrowed a cup of white sugar from the woman next door, and prepared a lavish tea tray worthy of the envy of her neighbours without letting her guest know.

There was a knock at the door. Before it creaked open, Apa Najab, sensing a stranger at the door, darted up the stairs. It was a young boy sent by the shoe shop to pick up a batch of finished shoes. Jumma Khan took out a few pairs of shoes from the narrow cupboard at his back and handed them to the boy.

While he was busy in the transaction, I had a good look at Jumma Khan’s face. The once tiny speck of white on his forehead now covered his entire face. In twenty odd years he had grown visibly old, wrinkled, and bowed. I could judge from the bandaged left index finger that his movements were not as precise as they used to be. Age was catching up with him.

A call for evening prayers from the neighborhood mosque brought an end to my visit. Apa Najab planted a farewell kiss on my forehead and repeated the blessings she had wished on me earlier. She was still talking when I stepped outside and onto the street.

Author’s note: This essay was originally written in 1994.

Dr. Sayed Amjad Hussain holds Emeritus professorships in Humanities and cardiovascular surgery at the University of Toledo, USA. He is also an op-ed columnist for Toledo Blade and daily Aaj of Peshawar.

Contact: aghaji@bex.net

The door opened with the same creak that it had for all those years. As if frozen in time, there squatted Jumma Khan, the shoemaker, in the tiny foyer at the base of the steps, busy making the boat-shaped native shoes called khussas.

I stepped into the tiny foyer illuminated by a few oblique rays of sunlight ricocheting in from the narrow street outside. He recognized me and stood up, dropping a few tools on the floor in the process.

“It is so good to see you, little Agha Ji”, he said enthusiastically as he embraced me in a strong, affectionate hug.“My God, it has been at least 20 winters since I last saw you! When did you come back from vilayat (foreign land)? How is your wife— oh excuse me, your Mem Sahib and how many children do you have?” I could hardly keep up with his rapid-fire questions.

We were suddenly interrupted by his wife, who suspecting some activity downstairs, could not resist getting involved. “O father of Qayum,” she called from top of the stairs, ”Who is visting?”

Apa Najab, the strong-willed, slave-driving, life-long wife of Jumma Khan, still reigned in that house. Jumma Khan, always the obedient husband, answered in excitement, “It is little Agha Ji, Amjood, who lives in vilayat.” He never could pronounce my name properly.

Apa Najab came running down the stairs, and before she could grab my head to plant a kiss and say a thousand prayers for me and my family, she corrected her husband, “Don’t call him little Amjood anymore. He is Doctor Sahib!”

We sat down, I on the little stool and Apa Najab on the bottom step. Jumma Khan took his seat on the low cushioned stool and we began reminiscing.

“How are the kids?”, I inquired.

Before Jumma Khan had a chance to open his mouth, Apa Najab chimed in, “Yusaf is a clerk at the bank, is married, and has two children”.

“How about Qayum”?

There was a brief silence. I didn’t have to wait for the answer, but she answered anyway. “He is still possessed by bad spirits. You remember one time, a long time ago, when he had taken to fits? Well, he still has those fits”. As if to change from a painful subject, she resumed talking about the good old times.

Qayum had been my grade-school classmate. He always hung around older boys, and rumour had it that he was gay. In order to cover for his late-evening activities, he claimed to have been possessed by spirits who wouldn’t let him come home on time. Apa Najab and Jumma Khan probably knew the real reason, but couldn’t do much about it. They consulted the mosque mullah and other holy men, but Qayum continued on his jolly way.

I had heard he still passed his time at the city park, loafing around. Society had provided a respectable cover: “possession by spirits”. It permitted him to indulge in activities that could not otherwise be condoned.

Jumma Khan interrupted the conversation to ask if I would like a cup of green tea. I said I would. He headed for the door to order a pot from the corner teashop. But Apa Najab, ever the mother hen, stopped him.

“You don’t order tea from the outside for a guest like our doctor Sahib. I will make some green tea myself.”

Now, it was not often that Apa Najab would whip up some tea for a visitor. Special visitors were the exception. For occasional visitors and friends, tea was customarily ordered from the tea shop at the street corner.

“Whatever happened to the people who lived across the street from you? I inquired.

“Oh, you mean Salam and Omar, the cap-makers?”

“Yes”

“Well, they are still here. They live in the same house. The brothers get along fine, but their wives don’t.”

“And what about Dr. Qureshi?”

“God bless his soul, he passed away two years ago. He was good to us. But his children are nothing like their father. His middle son runs the clinic, but he has neither his father’s knowledge nor the old man’s sense of charity. Their whole family is ruined.”

Dr. Qureshi was an interesting figure in the neighbourhood. Trained as a male hospital attendant, he spent quite a bit of time in the Middle East. Due to the lack of trained personnel in those countries in the 1940s and 1950s, he was put in charge of a small hospital. Years later he returned to Peshawar and opened a clinic on our street. With his meticulously manicured Van Dyke beard and a three-piece suit, he looked too elegant and too European to be a part of our neighbourhood. But, as Jumma Khan mentioned, he was kind and compassionate and never failed to tend to a sick person.

“And you remember Jalil Ghazi.” Jumma Khan was certainly savouring his excursion into the past. “He also died two summers ago. You remember how he used to hop all over town on one leg? Well, his joints gave up on him and he died a miserable death, confined to his bed. There were times when he hardly spent any time in his bachelor room, and then there were times when he couldn’t move without help. May Allah forgive all of us”.

Jalil Ghazi was a colourful personality. A confirmed bachelor, he lost one leg on a fateful day in April 1930. Never a brave man, Jalil found himself part of a political rally in Qissa Khwani Bazaar. An English police officer ordered the procession to stop. Instead he was pelted with rocks and bricks, severely injuring him. When verbal warnings failed to halt the advancing surge, the police opened fire. As a result hundreds of unarmed civilians died. Jalil was hit in the leg and it had to be amputated. Instantly the bullet wound made him a living legend. Thereafter he was to be found, on crutches, at the head of every gathering, whether it was a political rally, a neighbourhood funeral or a wedding.

At this time Apa Najab came down the stairs with a tray of green tea, saltine biscuits and sweets. The ingenious woman had apparently sent a neighbour’s boy to fetch the edibles from the bazaar, borrowed a cup of white sugar from the woman next door, and prepared a lavish tea tray worthy of the envy of her neighbours without letting her guest know.

There was a knock at the door. Before it creaked open, Apa Najab, sensing a stranger at the door, darted up the stairs. It was a young boy sent by the shoe shop to pick up a batch of finished shoes. Jumma Khan took out a few pairs of shoes from the narrow cupboard at his back and handed them to the boy.

While he was busy in the transaction, I had a good look at Jumma Khan’s face. The once tiny speck of white on his forehead now covered his entire face. In twenty odd years he had grown visibly old, wrinkled, and bowed. I could judge from the bandaged left index finger that his movements were not as precise as they used to be. Age was catching up with him.

A call for evening prayers from the neighborhood mosque brought an end to my visit. Apa Najab planted a farewell kiss on my forehead and repeated the blessings she had wished on me earlier. She was still talking when I stepped outside and onto the street.

Author’s note: This essay was originally written in 1994.

Dr. Sayed Amjad Hussain holds Emeritus professorships in Humanities and cardiovascular surgery at the University of Toledo, USA. He is also an op-ed columnist for Toledo Blade and daily Aaj of Peshawar.

Contact: aghaji@bex.net