During the fight against Taliban in Swat and Malakand a decade ago, hundreds of suspected militants were rounded up in operations and kept in secret detention cells for years. As their numbers grew, pressure to bring them into the open for trial in courts also increased. A regulation called Action (In Aid of Civil Power) Regulation 2011 was thus issued by the president in June that year to provide for the suspects in ‘internment centres’ awaiting trial by courts.

At the insistence of law enforcement agencies, it was given backdated effect to legalise detentions since 2008. It was argued at the time that without the retrospective, law enforcement agencies would, at some point, be exposed to the charge of enforced disappearances.

The backdated regulation was a compromise; bring out the secretly-held suspects in return for amnesty from prosecution. The president could issue the regulation only in respect of federal and provincial tribal areas, but there were hopes that, beginning with Swat and Malakand, enforced disappearances will one day come to an end throughout the country.

Alas, not only have enforced disappearances continued, but in the course of time, horror chambers were also created to legalise them.

As a result of the regulation, a number of internment centres were set up in both tribal areas and in some districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. However, no one knew exactly how many centres there were and how many detainees were held in each and for what crime. Suspicions grew as parliamentary questions were not answered and MPs not allowed to visit them. Over years they virtually became horror chambers of Pakistan.

The regulation also provided that those declared ‘whites’ by joint investigation teams were to be released while the ‘grey’ and ‘black’ categories were to be tried in courts. Objections were raised against giving the power of determining ‘whites’ and ‘blacks’ to the law enforcement agencies, but these objections were set aside with the assertion that detainees will finally be tried by courts.

When complaints mounted, the Supreme Court also took notice and in 2013 a three-judge bench headed by Justice Jawwad S Khawaja asked for detailed information.

In response to repeated demands by the court and expression of displeasure by the judge for not providing information, the federal government finally provided two lists.

One gave the location of the secret internment centres and the other contained the names of persons in charge of these centres. To the horror of many, the Frontier Corps (FC) forts in Chitral, Drosh, Mirkhani and Timergara also served as internment centres.

The regulation defined internment centres as “any compound, house, building, facility or any temporary or permanent structure that is notified by the governor or any officer authorised by him.” Through a mischievous interpretation of the words “any building,” the suspects were kept incommunicado in military forts.

There was no answer when the court asked as to what prevented the missing persons, wherever they may have been lodged, from meeting their relatives. Displeased, Justice Jawwad remarked, “Now we will see who is the commandant of these centres.” Hopes were raised but nothing much came out of that warning.

In May last year, the 25th constitutional amendment merged tribal areas in the province and abolished the powers of the president to issue regulations. Hopes were raised once again that internment centres will come to an end.

But those hopes were dashed when last month the provincial government enacted another legislation - KP Continuation of Laws in Erstwhile Fata Areas, 2019 - protecting presidential regulations, including the one that created the horror chambers.

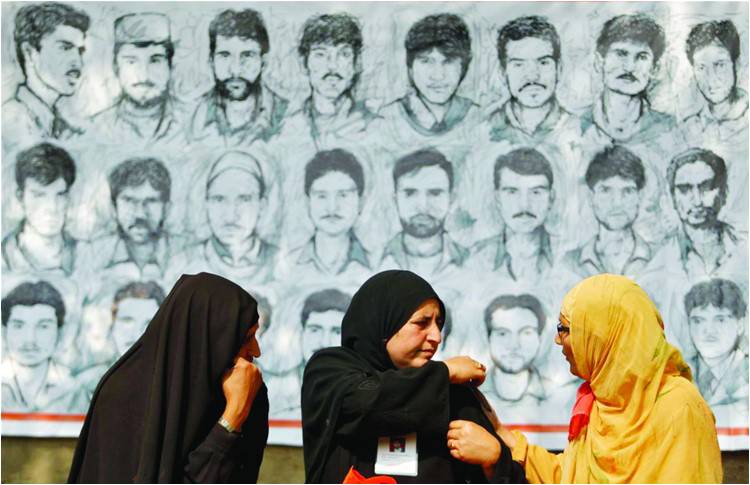

In petitions before courts, relatives of the internees have claimed that apart from holding prisoners in these centres for many years without any trial, they had not even been informed about the charges against them. Even those held on suspicion of affiliation with banned outfits have neither been charged nor tried for years, they complained. 10 filmer du inte får missa om du älskar spelautomater

The Peshawar High Court bench headed by the chief justice provided some relief by way of medical facilities to the internees, but the vires of the Regulation were not examined and the horror chambers remain in place.

During the hearings, however, the court wondered whether the presidential regulations still held the field even after the powers of president were withdrawn under the 25th Amendment. There were hints also that the petitioners could separately challenge the presidential regulation, as well as the latest provincial legislation protecting it.

About a fortnight ago, young lawyer Shabbir Hussain Gigyani actually moved the Peshawar High Court challenging the legislations and pleading that the internment centres be declared unconstitutional and all internees handed over to courts for trial. Once again hopes have been raised as the court issued notices last week.

As the matter is now before the court, no further comments are warranted. However, a word of caution for the likes of Advocate Gigyani fighting against internment centres.

The security establishment has strongly backed the presidential regulation from the very beginning. It was signed during president’s brief visit to Karachi without waiting for his return to Islamabad. Not only that, the establishment even prepared a press release asking that it be issued by the presidency after signing.

A peep into the mind set of the establishment is provided by some gems contained in the press release. “This law meets the international standards for ‘internment’ regime,” it said. Another gem: “The law also creates an obligation on the armed forces to comply with humanitarian law principles and human rights standards.” Yet another gem: “The law demonstrates improved control of the armed forces by the civilian democratic government.” And finally, “It is permissible under the Constitution of Pakistan.”

The Presidency, however, thought it unadvisable to opine on the constitutionality or meeting ‘international standards’ of the controversial internment centres. A simple one liner press release: “On the advice of the prime minister, the president today signed regulation titled Action in Aid of Civil Powers-2011 for FATA and PATA” was issued instead. It did not go down well with the establishment.

The Presidency refusing to certify ‘constitutionality’ or ‘meeting international standards’ of the internment centres has made little difference and Pakistan’s horror chambers remain.

The writer a former senator and also served as a presidential spokesperson

At the insistence of law enforcement agencies, it was given backdated effect to legalise detentions since 2008. It was argued at the time that without the retrospective, law enforcement agencies would, at some point, be exposed to the charge of enforced disappearances.

The backdated regulation was a compromise; bring out the secretly-held suspects in return for amnesty from prosecution. The president could issue the regulation only in respect of federal and provincial tribal areas, but there were hopes that, beginning with Swat and Malakand, enforced disappearances will one day come to an end throughout the country.

Alas, not only have enforced disappearances continued, but in the course of time, horror chambers were also created to legalise them.

As a result of the regulation, a number of internment centres were set up in both tribal areas and in some districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. However, no one knew exactly how many centres there were and how many detainees were held in each and for what crime. Suspicions grew as parliamentary questions were not answered and MPs not allowed to visit them. Over years they virtually became horror chambers of Pakistan.

The regulation also provided that those declared ‘whites’ by joint investigation teams were to be released while the ‘grey’ and ‘black’ categories were to be tried in courts. Objections were raised against giving the power of determining ‘whites’ and ‘blacks’ to the law enforcement agencies, but these objections were set aside with the assertion that detainees will finally be tried by courts.

When complaints mounted, the Supreme Court also took notice and in 2013 a three-judge bench headed by Justice Jawwad S Khawaja asked for detailed information.

In response to repeated demands by the court and expression of displeasure by the judge for not providing information, the federal government finally provided two lists.

One gave the location of the secret internment centres and the other contained the names of persons in charge of these centres. To the horror of many, the Frontier Corps (FC) forts in Chitral, Drosh, Mirkhani and Timergara also served as internment centres.

The regulation defined internment centres as “any compound, house, building, facility or any temporary or permanent structure that is notified by the governor or any officer authorised by him.” Through a mischievous interpretation of the words “any building,” the suspects were kept incommunicado in military forts.

There was no answer when the court asked as to what prevented the missing persons, wherever they may have been lodged, from meeting their relatives. Displeased, Justice Jawwad remarked, “Now we will see who is the commandant of these centres.” Hopes were raised but nothing much came out of that warning.

In May last year, the 25th constitutional amendment merged tribal areas in the province and abolished the powers of the president to issue regulations. Hopes were raised once again that internment centres will come to an end.

But those hopes were dashed when last month the provincial government enacted another legislation - KP Continuation of Laws in Erstwhile Fata Areas, 2019 - protecting presidential regulations, including the one that created the horror chambers.

In petitions before courts, relatives of the internees have claimed that apart from holding prisoners in these centres for many years without any trial, they had not even been informed about the charges against them. Even those held on suspicion of affiliation with banned outfits have neither been charged nor tried for years, they complained. 10 filmer du inte får missa om du älskar spelautomater

The Peshawar High Court bench headed by the chief justice provided some relief by way of medical facilities to the internees, but the vires of the Regulation were not examined and the horror chambers remain in place.

During the hearings, however, the court wondered whether the presidential regulations still held the field even after the powers of president were withdrawn under the 25th Amendment. There were hints also that the petitioners could separately challenge the presidential regulation, as well as the latest provincial legislation protecting it.

About a fortnight ago, young lawyer Shabbir Hussain Gigyani actually moved the Peshawar High Court challenging the legislations and pleading that the internment centres be declared unconstitutional and all internees handed over to courts for trial. Once again hopes have been raised as the court issued notices last week.

As the matter is now before the court, no further comments are warranted. However, a word of caution for the likes of Advocate Gigyani fighting against internment centres.

The security establishment has strongly backed the presidential regulation from the very beginning. It was signed during president’s brief visit to Karachi without waiting for his return to Islamabad. Not only that, the establishment even prepared a press release asking that it be issued by the presidency after signing.

A peep into the mind set of the establishment is provided by some gems contained in the press release. “This law meets the international standards for ‘internment’ regime,” it said. Another gem: “The law also creates an obligation on the armed forces to comply with humanitarian law principles and human rights standards.” Yet another gem: “The law demonstrates improved control of the armed forces by the civilian democratic government.” And finally, “It is permissible under the Constitution of Pakistan.”

The Presidency, however, thought it unadvisable to opine on the constitutionality or meeting ‘international standards’ of the controversial internment centres. A simple one liner press release: “On the advice of the prime minister, the president today signed regulation titled Action in Aid of Civil Powers-2011 for FATA and PATA” was issued instead. It did not go down well with the establishment.

The Presidency refusing to certify ‘constitutionality’ or ‘meeting international standards’ of the internment centres has made little difference and Pakistan’s horror chambers remain.

The writer a former senator and also served as a presidential spokesperson