Back in the good old 1970s, the Municipal Stadium, B-Block Satellite Town, Rawalpindi, was not as well known as the Lords or Oval cricket grounds of England, but if one were to seek the true spirit of the game and all the excitement and surprise that went with it, the humble municipal stadium was the premier venue to head out for.

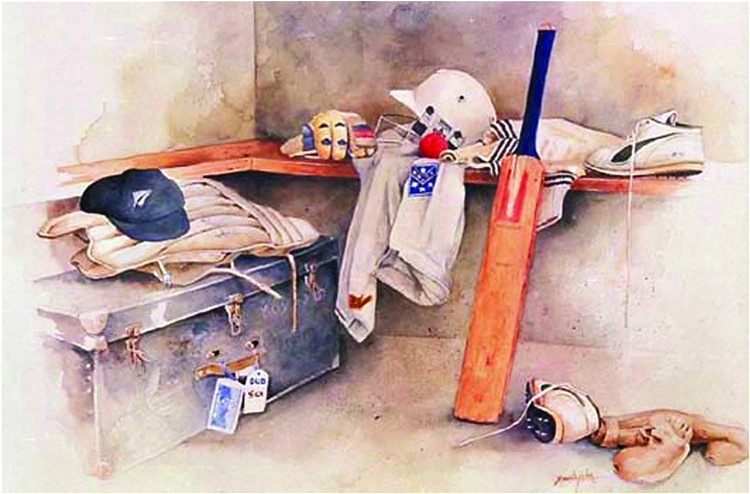

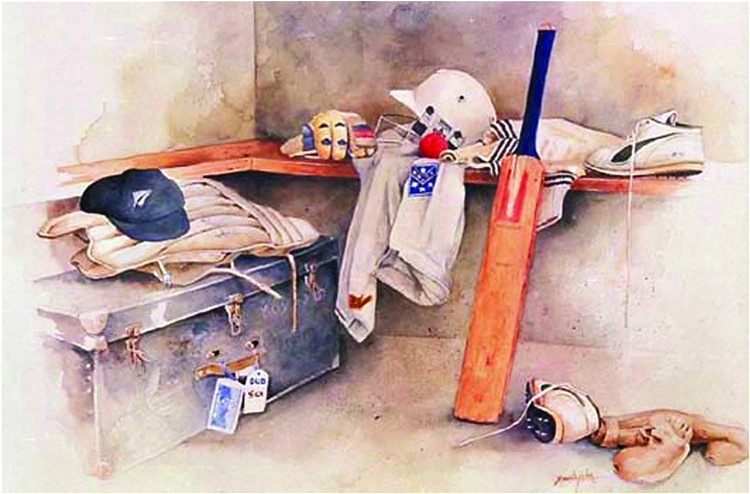

Teams would come from all over Rawalpindi tagging along their cricketing gear in bulky aluminum trunks. The players themselves were truly a mixed bag. The physiques ranged from large pot bellies to nearly concave stomachs. There could be a twelve-year-old prodigy and an unfit and unskilled fifty-year-old enthusiast who was most likely the financier of the team. One trait common to all the players was that they were excellent hecklers. The barbs traded were as much fun as the actual game. A fielder slow in chasing a ball would be greeted with shouts of, ”should we order a rickshaw for you?” and someone who dropped a catch would receive a taunt, “bateray pakar rahey ho!” (You’re catching partridges!)

Cheating in scoring was an accepted feature of the matches. In those computer-free days, ledger-sized registers were used for keeping the details of the scoring. The term used for fudging the score was “milawat” (contamination). If one team failed to keep the score of the other team, it was certain that there would be at least twenty runs added to the score. Even if both teams kept the score there were always arguments about the accuracy of the figures. But the competitiveness never spilled over to fights and the matches were always played in the true spirit of cricket – the gentleman’s game.

Sunday, a usual match day, was good for the business of street vendors, who would turn up at the stadium with their carts loaded with samosas, pakoras, and bun-kabab, which were quickly devoured by the players and spectators at lunch break. Whatever was left was bought by the winning team to celebrate.

While the rules by which cricket was played in the stadium were by the book, the terminology used was quite different from the accepted lexicon. Bails, a word alien to Urdu or Punjabi, became Wills, after the familiar cigarette brand. Fortunately, the term Captain stayed and did not take on the name of the other famous brand Capstan. The vociferous shout of “How’s that?” sometimes became “Outs that?” and on other occasions “Howze”. The matter was debated but never settled. New types of bowling came into existence. Beyond the standard “in-swing” and “out-swing” varieties of fast bowling, “centre swing”, the definition of which was never agreed upon, became a type of surprise delivery. Cut shots were named after famous film actors and a particularly stylish slice through the slips was christened “Dillip Cut”. Somehow a “wide ball” metamorphosed into “white ball”. A flighted spin delivery was labeled “Khota Flight”. There were some innovations like “thappa catch” - which was not a catch at all, as it was grasped by a fielder after the first bounce of the ball. There was always a controversy as to whether a catch was genuine or of the thappa variety. In such matters the partiality of the umpire to one team or the other was the deciding factor. Controversy would also erupt in the matter of Leg Before Wicket (LBW) as neither the umpires nor the players were fully knowledgeable in this tricky type of dismissal. A variant of LBW by the raunchy name of TBW also caught the imagination of the creative cricketers. This form of dismissal was adjudged when the ball hit a sensitive part of the male anatomy. Illegal arm action was called “watta ball” and caused heated debates on the field as to the legitimacy of the bowler’s action.

Much like the innovative terms that defied logic, there were cricketers who defied any established pattern of batting or bowling. The matches in the municipal stadium would often feature mohallah talent like Ahsan whose father, nicknamed by us as “Mr. 420” for his putative fraudulent dealings, had sired ten children. They were all exceptionally talented in “kabooter baazi”, “murgh baazi”, dog fights, and other such useful sports. But Ahsan, the eldest, was a talented bowler. He could turn a ball from outside of the leg stump straight on to the middle stump. But his problem was consistency and focus. Being an avid kabooter baaz, his eyes would sometimes wander off to the sky looking for his beloved kabooters (pigeons). This would result in the wrong line and length. A few charas (hashish) loaded cigarettes were not helping his bowling either and his cricketing career was cut short.

But the most legendary character was known simply as Ahmed Sahib due to his serious demeanour and relatively advanced age. He was a tall, well built man, who seemed to be asleep when he was awake and walking. He never spoke much. He had a natural relationship to cricket because his house was located at the edge of the stadium and he would simply walk in to watch a match. I was personally present on a historic Sunday when the Young Star cricket club turned up for a match, one star short. Mr. Munir, the captain of the team noticed Mr. Ahmed standing calmly by the boundary, waiting for the game to start. Quite likely as a mark of his love for the game of cricket, Ahmed Sahib always dressed in whites on Sundays. In an historic instant, Mr. Ahmed was awarded the cap for the Young Stars Their opponents, Kali Tanki Gymkhana, won the toss, chose to bat first and put on a healthy 180 runs on the board.

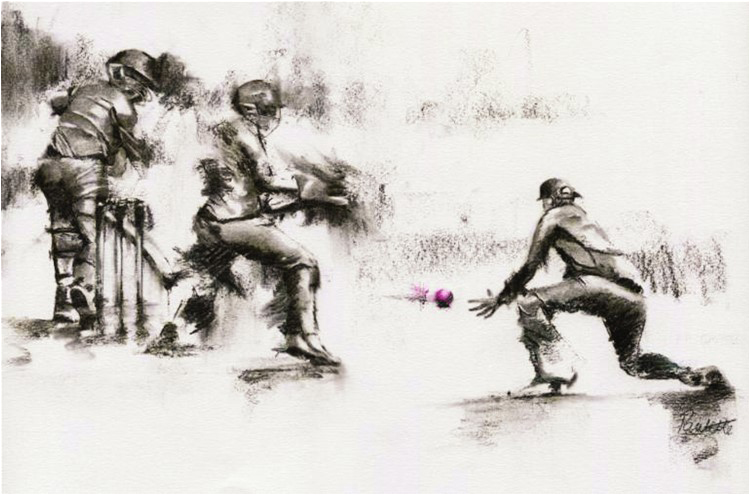

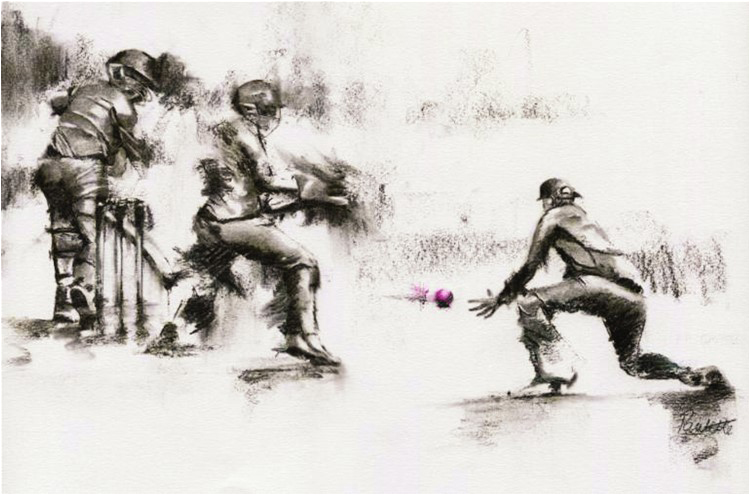

Young Stars did not make a good start and lost two quick wickets in the early overs. With a gritty fifty by the Captain Mr. Munir the score started looking respectable. Then came the debacle. Mr. Munir’s “wills” went flying with what was likely a vicious centre swing ball. Mr. Munir had expected an outswinger and was shaping to play a Dillip Cut. Three more wickets fell in quick succession leaving the Young Stars at a precarious position of 144 for the loss of 8 wickets. Kali Tanki Gymkhana was smelling blood and their supporters were now chanting “Dung Star, Dung Star”.

The new batsman in was Mr. Ahmed. He walked up to the crease in his usual sleepwalker’s gait. The first ball was a rising delivery aimed at the middle stump that hit Mr. Ahmed smack in the privates and a fervent appeal for a LBW/TBW went up. Not out, said the umpire. Mr. Ahmed showed no sign of being hit at such a sensitive spot. The bowler, confident of his first strategic strike, sent in another rising delivery. In the blink of an eye that ball disappeared from the stadium, flying like a missile over the bowler’s head. It was hit with such stunning power and ease that not a fielder moved. Now the bowler decided to go for a bouncer. Mr. Ahmed swung his bat at it like a whirling dervish and it was another six that landed at the gate of the batsman’s house. A close infielder later swore that Mr. Ahmed had played that shot with his eyes closed. The hapless bowler was now panicking. He gave away a “white ball” but the next one was again hit for a six. The derisive shouts of “bowler’s name?” were raised by the supporters of Young Star. The next delivery was perfectly decent and pitched slightly short of a length. Much to the horror of the bowler, Mr. Ahmed calmly waited for it, then casually lifted it over mid-off and the ball once again went flying over the boundary wall of the stadium and into the grounds of the neighbouring Muslim High School No. 1. To add insult to injury the delivery was declared a no ball. The writing was on the wall now. The bowler was sweating profusely. The required runs were just four now. The tension in the stadium could be cut with a knife and Mr. Ahmed was in a trance-like state. The final ball was an attempted yorker, a bad idea against Mr. Ahmed, who had a yard-long stride. He stepped up, made a full toss of the delivery and hit it straight over the head of the bowler, nearly decapitating him in the process. Six balls, six sixes! The match was over. Mr. Ahmed calmly walked back to his house, oblivious of the uproar in the stadium.

Mr. Ahmed never played again, but the legend of the six sixes became part of the cricketing folklore of the Municipal Stadium, B-Block Satellite Town, Rawalpindi.

Teams would come from all over Rawalpindi tagging along their cricketing gear in bulky aluminum trunks. The players themselves were truly a mixed bag. The physiques ranged from large pot bellies to nearly concave stomachs. There could be a twelve-year-old prodigy and an unfit and unskilled fifty-year-old enthusiast who was most likely the financier of the team. One trait common to all the players was that they were excellent hecklers. The barbs traded were as much fun as the actual game. A fielder slow in chasing a ball would be greeted with shouts of, ”should we order a rickshaw for you?” and someone who dropped a catch would receive a taunt, “bateray pakar rahey ho!” (You’re catching partridges!)

Cheating in scoring was an accepted feature of the matches. In those computer-free days, ledger-sized registers were used for keeping the details of the scoring. The term used for fudging the score was “milawat” (contamination). If one team failed to keep the score of the other team, it was certain that there would be at least twenty runs added to the score. Even if both teams kept the score there were always arguments about the accuracy of the figures. But the competitiveness never spilled over to fights and the matches were always played in the true spirit of cricket – the gentleman’s game.

Sunday, a usual match day, was good for the business of street vendors, who would turn up at the stadium with their carts loaded with samosas, pakoras, and bun-kabab, which were quickly devoured by the players and spectators at lunch break. Whatever was left was bought by the winning team to celebrate.

While the rules by which cricket was played in the stadium were by the book, the terminology used was quite different from the accepted lexicon. Bails, a word alien to Urdu or Punjabi, became Wills, after the familiar cigarette brand. Fortunately, the term Captain stayed and did not take on the name of the other famous brand Capstan. The vociferous shout of “How’s that?” sometimes became “Outs that?” and on other occasions “Howze”. The matter was debated but never settled. New types of bowling came into existence. Beyond the standard “in-swing” and “out-swing” varieties of fast bowling, “centre swing”, the definition of which was never agreed upon, became a type of surprise delivery. Cut shots were named after famous film actors and a particularly stylish slice through the slips was christened “Dillip Cut”. Somehow a “wide ball” metamorphosed into “white ball”. A flighted spin delivery was labeled “Khota Flight”. There were some innovations like “thappa catch” - which was not a catch at all, as it was grasped by a fielder after the first bounce of the ball. There was always a controversy as to whether a catch was genuine or of the thappa variety. In such matters the partiality of the umpire to one team or the other was the deciding factor. Controversy would also erupt in the matter of Leg Before Wicket (LBW) as neither the umpires nor the players were fully knowledgeable in this tricky type of dismissal. A variant of LBW by the raunchy name of TBW also caught the imagination of the creative cricketers. This form of dismissal was adjudged when the ball hit a sensitive part of the male anatomy. Illegal arm action was called “watta ball” and caused heated debates on the field as to the legitimacy of the bowler’s action.

Much like the innovative terms that defied logic, there were cricketers who defied any established pattern of batting or bowling. The matches in the municipal stadium would often feature mohallah talent like Ahsan whose father, nicknamed by us as “Mr. 420” for his putative fraudulent dealings, had sired ten children. They were all exceptionally talented in “kabooter baazi”, “murgh baazi”, dog fights, and other such useful sports. But Ahsan, the eldest, was a talented bowler. He could turn a ball from outside of the leg stump straight on to the middle stump. But his problem was consistency and focus. Being an avid kabooter baaz, his eyes would sometimes wander off to the sky looking for his beloved kabooters (pigeons). This would result in the wrong line and length. A few charas (hashish) loaded cigarettes were not helping his bowling either and his cricketing career was cut short.

But the most legendary character was known simply as Ahmed Sahib due to his serious demeanour and relatively advanced age. He was a tall, well built man, who seemed to be asleep when he was awake and walking. He never spoke much. He had a natural relationship to cricket because his house was located at the edge of the stadium and he would simply walk in to watch a match. I was personally present on a historic Sunday when the Young Star cricket club turned up for a match, one star short. Mr. Munir, the captain of the team noticed Mr. Ahmed standing calmly by the boundary, waiting for the game to start. Quite likely as a mark of his love for the game of cricket, Ahmed Sahib always dressed in whites on Sundays. In an historic instant, Mr. Ahmed was awarded the cap for the Young Stars Their opponents, Kali Tanki Gymkhana, won the toss, chose to bat first and put on a healthy 180 runs on the board.

Young Stars did not make a good start and lost two quick wickets in the early overs. With a gritty fifty by the Captain Mr. Munir the score started looking respectable. Then came the debacle. Mr. Munir’s “wills” went flying with what was likely a vicious centre swing ball. Mr. Munir had expected an outswinger and was shaping to play a Dillip Cut. Three more wickets fell in quick succession leaving the Young Stars at a precarious position of 144 for the loss of 8 wickets. Kali Tanki Gymkhana was smelling blood and their supporters were now chanting “Dung Star, Dung Star”.

The new batsman in was Mr. Ahmed. He walked up to the crease in his usual sleepwalker’s gait. The first ball was a rising delivery aimed at the middle stump that hit Mr. Ahmed smack in the privates and a fervent appeal for a LBW/TBW went up. Not out, said the umpire. Mr. Ahmed showed no sign of being hit at such a sensitive spot. The bowler, confident of his first strategic strike, sent in another rising delivery. In the blink of an eye that ball disappeared from the stadium, flying like a missile over the bowler’s head. It was hit with such stunning power and ease that not a fielder moved. Now the bowler decided to go for a bouncer. Mr. Ahmed swung his bat at it like a whirling dervish and it was another six that landed at the gate of the batsman’s house. A close infielder later swore that Mr. Ahmed had played that shot with his eyes closed. The hapless bowler was now panicking. He gave away a “white ball” but the next one was again hit for a six. The derisive shouts of “bowler’s name?” were raised by the supporters of Young Star. The next delivery was perfectly decent and pitched slightly short of a length. Much to the horror of the bowler, Mr. Ahmed calmly waited for it, then casually lifted it over mid-off and the ball once again went flying over the boundary wall of the stadium and into the grounds of the neighbouring Muslim High School No. 1. To add insult to injury the delivery was declared a no ball. The writing was on the wall now. The bowler was sweating profusely. The required runs were just four now. The tension in the stadium could be cut with a knife and Mr. Ahmed was in a trance-like state. The final ball was an attempted yorker, a bad idea against Mr. Ahmed, who had a yard-long stride. He stepped up, made a full toss of the delivery and hit it straight over the head of the bowler, nearly decapitating him in the process. Six balls, six sixes! The match was over. Mr. Ahmed calmly walked back to his house, oblivious of the uproar in the stadium.

Mr. Ahmed never played again, but the legend of the six sixes became part of the cricketing folklore of the Municipal Stadium, B-Block Satellite Town, Rawalpindi.