Some months ago my interest was piqued when a white malmal farshi pajama from the 1920s belonging to the family’s great aunt Amina or Chachi Bibi, as she was called, was brought to my attention. The garment was clearly a treasured possession, which she had carried with her belongings in November of 1947 when she and her husband were forced to migrate and leave their ancestral home in Eastern Punjab on three days’ notice.

For her middle daughter Tahira, who recently passed away, the farshi later became a symbol of longing and loss. It rekindled not just the memories of her mother but the suppressed longing for a history, a heritage and an identity that was their family hallmark for generations; and which had scattered away with the merciless uprooting. Over time, it became Tahira’s rumination on the memory of loss; and preserving this seemingly mundane garment, therapeutic.

Chachi Bibi was the wife of one of five brothers of the Hakeemwala clan of Mohalla Ansar, who lived in Panipat as a close-knit joint family. With the husbands away working in other parts of India, it was the matriarchs who ran affairs of the house and became the official caretakers of the agricultural land.

Quite evidently Chachi Bibi was a strong woman who at 5 feet 9 inches eventually raised nine children. A gifted storyteller, her fantastic fables have been published by her children.

It is said that in the family, virtually everything was bought and produced in bulk for all the young wives and daughters each season. White was the colour worn in the hot summer months from April to June, when chikan and net kurtas and dupattas were worn with kharra pajamas around the house. By family accounts white farshis were worn over the pajama when stepping outside the private domain of the house, by all the women. However, contrary to its name the garment only touched the indoor farsh (floor) of any place, as the women traveled exclusively in a covered doli. Colours gradually came to inhabit their wardrobes with the advent of barsat (the rainy season), when multi-coloured chintz shirts would be worn starched, sprinkled with abrak and “chunna hua” dupattas with lehriya and chundri patterns were ordered for the season.

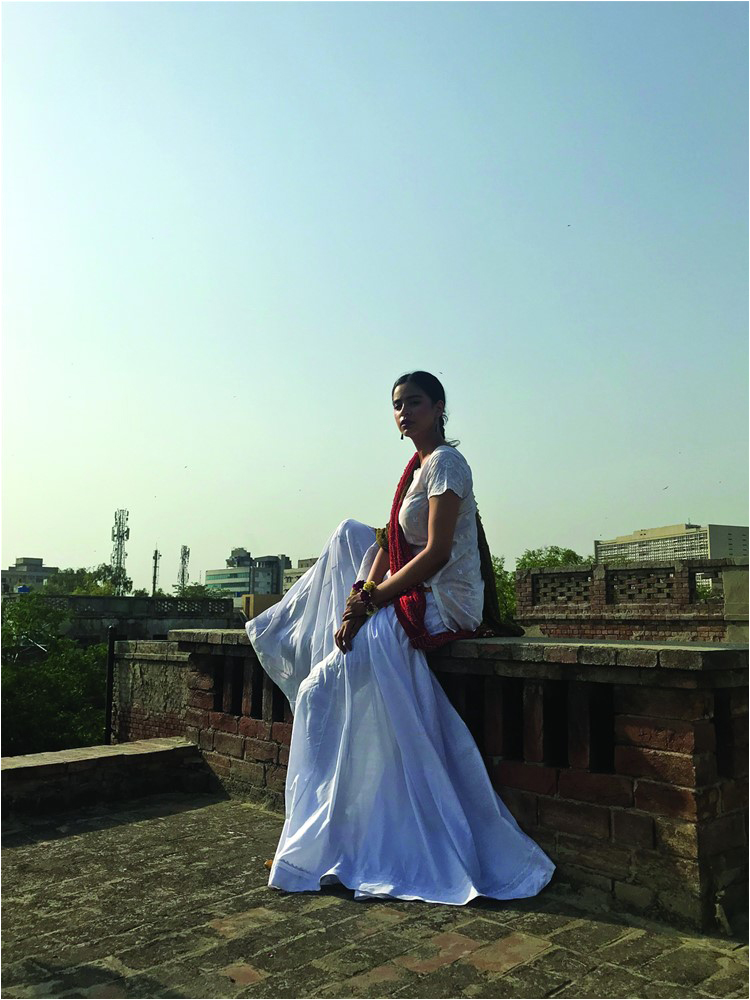

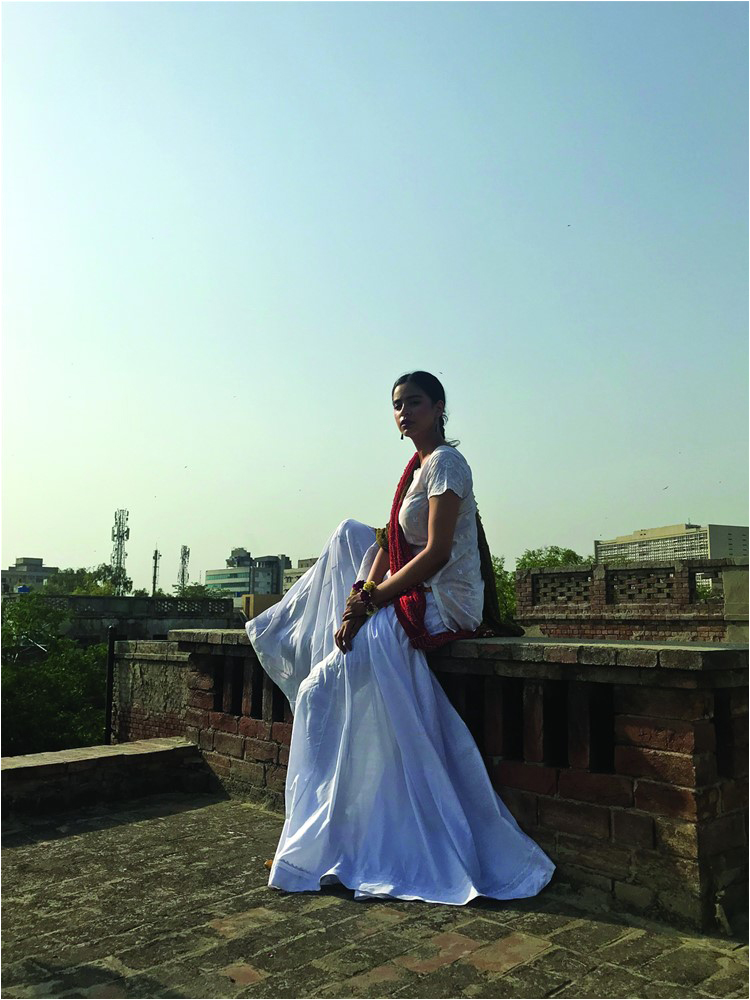

The malmal farshi, a garment with an incredible cut and flair with almost a dozen panels carefully sewn together, had hand-turned seams and was simply finished with a 3-inch bias border and a chikan braid that had been invisibly attached with handmade kingri of the main fabric. Around the waistband was an inexplicable red strip, and upon enquiry, Tahira explained (as narrated by her daughter-in-law Rabiya, quoting a conversation) that it was a mark of the owner. When they were all at home, everyone’s white farshi hung on hooks in the central room, identified only by the colour of the waistband.

Chachi Bibi’s farshi caught the attention of all those who set their eyes on it. Fascinated by its simplicity – which spoke volumes – friends, family, artists and designers saw its quiet style statement as a peek into an era where life was uncomplicated, and as an ostensible reminder of what is missing.

Attempting to replicate it as-it-was seemed the most plausible option, since it would leave undisturbed the proportions and dimensions. Better Tomorrow, a women’s cooperative who hand-stitch traditional ghararas and garments for women and children and who were commissioned for a small line of cotton ghararas for Eid, rose to the challenge with overwhelming success. They managed to produce the exact replica.

As soon as it arrived, it begged to be worn and undoubtedly it would be a perfect fit for the great grand daughter of Chachi Bibi, the young and accomplished Meher, an English major, who was as tall as her great grand mother and had recently embarked on a modeling career. But the farshi was not just a mere fashion statement. It came to represent a stimulus by means of which to repopulate collective memory. The curatorial premise thus stated, a team came together consisting of her grand daughters and great grand daughters who are all accomplished artists, photography students and a lawyer turned entrepreneur. Zainab and Zehra, Tahira’s grand daughters, would do the photography, while Nisha, a grand daughter, would contribute to the art direction. All of them agreed to model, including Zehra, another great granddaughter and her little girls.

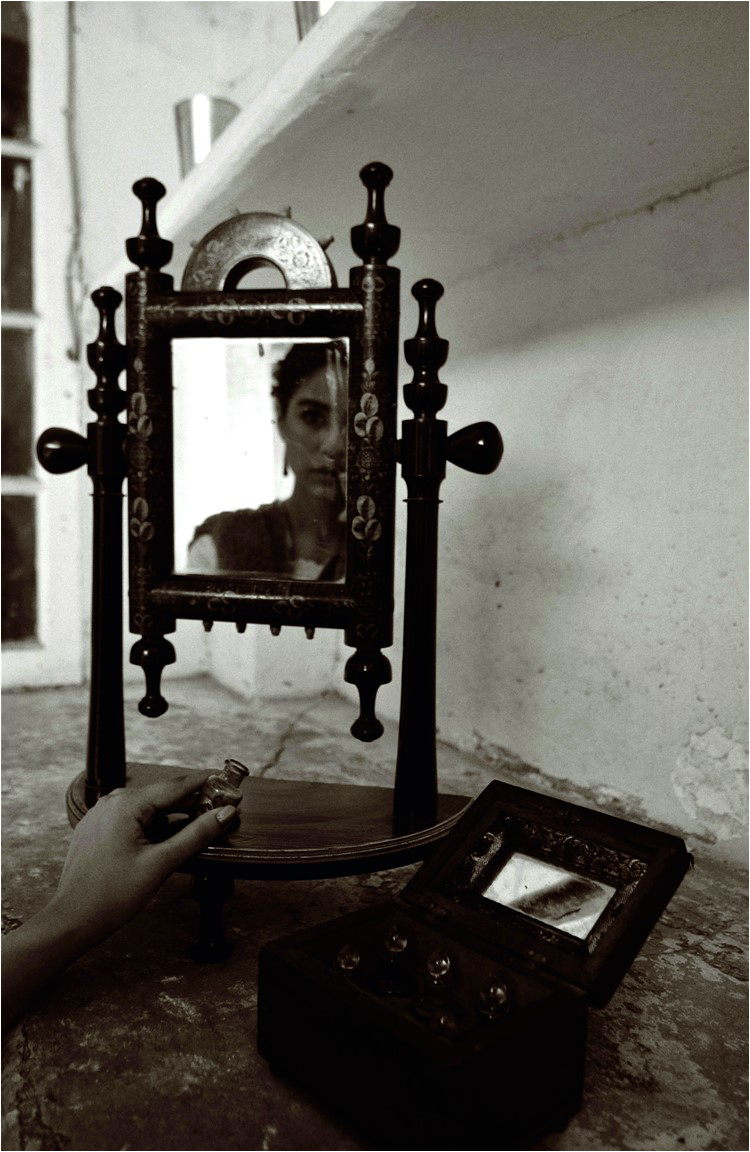

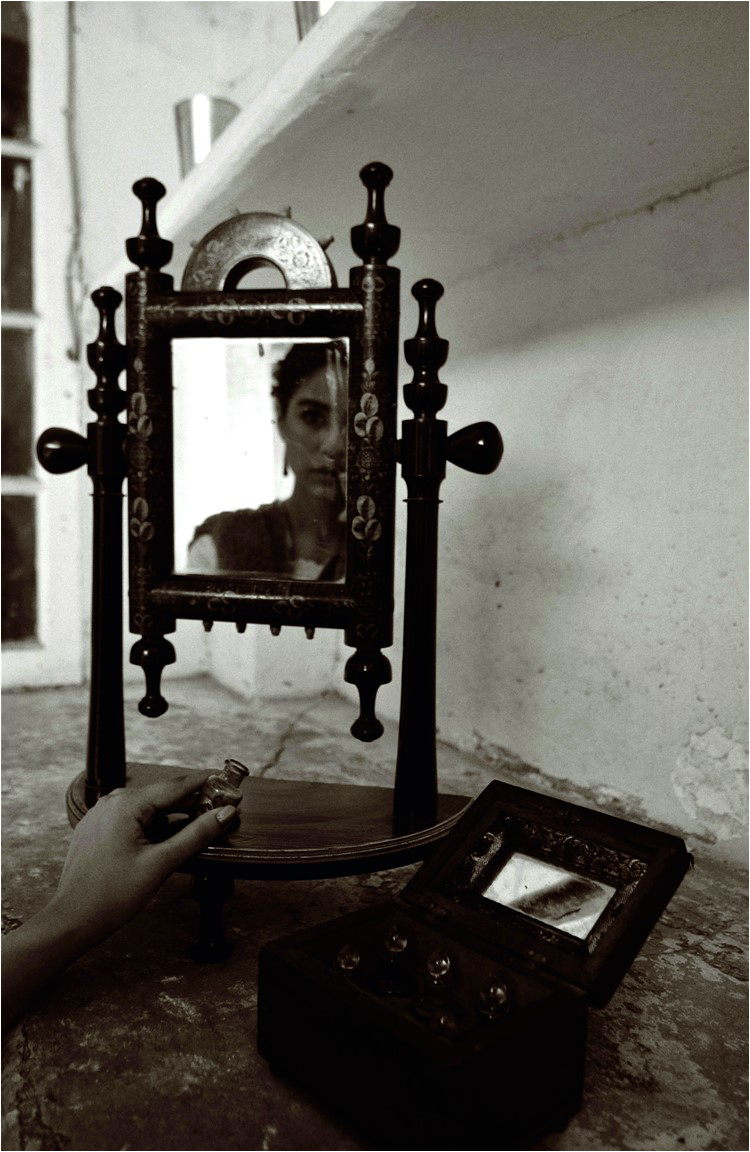

It became evident in no time that a befitting back drop for this would be the old and now uninhabited Lahore home of the extended family, which was once witness to the upheavals of the events of Partition. Its flaying walls a metaphor for the lives that fled and the lives that inhabited it, during and after the turmoil of events. The fact that almost each child of Chachi Bibi had also at some point stayed here, only added to its relevance. An immersion into this “intangible heritage” thus became an imperative for the endeavour – evoking and honouring the culture, the objects and memories of those who had occupied this real space, notwithstanding its colonial Lahore architectural merits.

The idea was not to recreate life in times bygone but to put in the spotlight evidence from a past and expose a tiny sliver of the layers of its sediments.

Afarshi is a long voluminous garment that generously falls to the ground and when standing or walking – with a long train or trail. The copious flair is meant to be pulled up, folded and either tucked at the waist or draped over the left arm for ease of walking and getting on with life. The word comes from ‘farsh’ or the ground/floor, which the garment trails on.

Whereas the garment was worn in all parts of the UP, Delhi, Hyderabad and beyond, the design elements of these garments varied somewhat with geography and time. Various permutations of the traditional farshi garments may be seen as heirlooms and in private collections and museums today.

The ones where the top and bottom are almost equal halves in length are referred to as ghararas. There are others with a longer paincha and much narrower gote at the bottom. It appears that the term “farshi gharara” is a twentieth-century construct, before which all such garments seem to have been referred to as a farshi pajama, or simply, farshi.

They all have a paincha (the top half) with kalis or triangular sections beginning at the waist and a gote (the bottom half) that spreads out. The lower half is usually cut on the bias for the flair or simply gathered. All the variations have a waistband attached on the top with a drawstring. A traditional farshi or “kalidar” pajama is a two-legged garment, put together in two parts as noted above. In the upper half a large section is cut straight (like a paincha) while the remaining is a whole host of ‘kalis’ or triangular sections, at times of varying sizes and shapes, to provide the requisite flair and train. In a number of instances there may be a patti, cut on the bias, varying between 4 and 12 inches approximately, added as a continuous border at the bottom. This border, all around the circumference, is not only for decorative purposes but also provides the requisite weight for the whole garment to drape or ‘fall’ in place (not very dissimilar in principle to the sari fall)

These took the form of wedding dresses made in elaborate pote and kimkhwab fabric, with our without zari wires, and a variety of embellishments in zardozi, salma, dabka, sequins and karchob work etc. The ones meant for occasional wear made in embossed, textured, handwoven silks, while plain cotton ones for everyday wear were made in cotton cheent (small prints in bright colours) or white muslin to brave the brutal Subcontinental summer.

Ghararas are what became de rigueur in the 1940s and 1950s as occasional/formal wear together with saris.

And so the elaborate farshis were confined to heirloom trunks.

For her middle daughter Tahira, who recently passed away, the farshi later became a symbol of longing and loss. It rekindled not just the memories of her mother but the suppressed longing for a history, a heritage and an identity that was their family hallmark for generations; and which had scattered away with the merciless uprooting. Over time, it became Tahira’s rumination on the memory of loss; and preserving this seemingly mundane garment, therapeutic.

Chachi Bibi was the wife of one of five brothers of the Hakeemwala clan of Mohalla Ansar, who lived in Panipat as a close-knit joint family. With the husbands away working in other parts of India, it was the matriarchs who ran affairs of the house and became the official caretakers of the agricultural land.

Quite evidently Chachi Bibi was a strong woman who at 5 feet 9 inches eventually raised nine children. A gifted storyteller, her fantastic fables have been published by her children.

Concept: Fatma Shah

Photography: Zainab Hussain & Zehra Hussain

Art Direction: Nisha Hasan & Fatma

Model: Meher Hasan

Accompanied by: Zehra Hasan, Bano & Zaina

It is said that in the family, virtually everything was bought and produced in bulk for all the young wives and daughters each season. White was the colour worn in the hot summer months from April to June, when chikan and net kurtas and dupattas were worn with kharra pajamas around the house. By family accounts white farshis were worn over the pajama when stepping outside the private domain of the house, by all the women. However, contrary to its name the garment only touched the indoor farsh (floor) of any place, as the women traveled exclusively in a covered doli. Colours gradually came to inhabit their wardrobes with the advent of barsat (the rainy season), when multi-coloured chintz shirts would be worn starched, sprinkled with abrak and “chunna hua” dupattas with lehriya and chundri patterns were ordered for the season.

The malmal farshi, a garment with an incredible cut and flair with almost a dozen panels carefully sewn together, had hand-turned seams and was simply finished with a 3-inch bias border and a chikan braid that had been invisibly attached with handmade kingri of the main fabric. Around the waistband was an inexplicable red strip, and upon enquiry, Tahira explained (as narrated by her daughter-in-law Rabiya, quoting a conversation) that it was a mark of the owner. When they were all at home, everyone’s white farshi hung on hooks in the central room, identified only by the colour of the waistband.

Chachi Bibi’s farshi caught the attention of all those who set their eyes on it. Fascinated by its simplicity – which spoke volumes – friends, family, artists and designers saw its quiet style statement as a peek into an era where life was uncomplicated, and as an ostensible reminder of what is missing.

Attempting to replicate it as-it-was seemed the most plausible option, since it would leave undisturbed the proportions and dimensions. Better Tomorrow, a women’s cooperative who hand-stitch traditional ghararas and garments for women and children and who were commissioned for a small line of cotton ghararas for Eid, rose to the challenge with overwhelming success. They managed to produce the exact replica.

Chachi Bibi’s farshi caught the attention of all those who set their eyes on it. Fascinated by its simplicity – which spoke volumes – friends, family, artists and designers saw its quiet style statement as a peek into an era where life was uncomplicated, and as an ostensible reminder of what is missing.

As soon as it arrived, it begged to be worn and undoubtedly it would be a perfect fit for the great grand daughter of Chachi Bibi, the young and accomplished Meher, an English major, who was as tall as her great grand mother and had recently embarked on a modeling career. But the farshi was not just a mere fashion statement. It came to represent a stimulus by means of which to repopulate collective memory. The curatorial premise thus stated, a team came together consisting of her grand daughters and great grand daughters who are all accomplished artists, photography students and a lawyer turned entrepreneur. Zainab and Zehra, Tahira’s grand daughters, would do the photography, while Nisha, a grand daughter, would contribute to the art direction. All of them agreed to model, including Zehra, another great granddaughter and her little girls.

It became evident in no time that a befitting back drop for this would be the old and now uninhabited Lahore home of the extended family, which was once witness to the upheavals of the events of Partition. Its flaying walls a metaphor for the lives that fled and the lives that inhabited it, during and after the turmoil of events. The fact that almost each child of Chachi Bibi had also at some point stayed here, only added to its relevance. An immersion into this “intangible heritage” thus became an imperative for the endeavour – evoking and honouring the culture, the objects and memories of those who had occupied this real space, notwithstanding its colonial Lahore architectural merits.

The idea was not to recreate life in times bygone but to put in the spotlight evidence from a past and expose a tiny sliver of the layers of its sediments.

Story of the Farshi – from everyday wear to heirloom

Afarshi is a long voluminous garment that generously falls to the ground and when standing or walking – with a long train or trail. The copious flair is meant to be pulled up, folded and either tucked at the waist or draped over the left arm for ease of walking and getting on with life. The word comes from ‘farsh’ or the ground/floor, which the garment trails on.

Whereas the garment was worn in all parts of the UP, Delhi, Hyderabad and beyond, the design elements of these garments varied somewhat with geography and time. Various permutations of the traditional farshi garments may be seen as heirlooms and in private collections and museums today.

The ones where the top and bottom are almost equal halves in length are referred to as ghararas. There are others with a longer paincha and much narrower gote at the bottom. It appears that the term “farshi gharara” is a twentieth-century construct, before which all such garments seem to have been referred to as a farshi pajama, or simply, farshi.

They all have a paincha (the top half) with kalis or triangular sections beginning at the waist and a gote (the bottom half) that spreads out. The lower half is usually cut on the bias for the flair or simply gathered. All the variations have a waistband attached on the top with a drawstring. A traditional farshi or “kalidar” pajama is a two-legged garment, put together in two parts as noted above. In the upper half a large section is cut straight (like a paincha) while the remaining is a whole host of ‘kalis’ or triangular sections, at times of varying sizes and shapes, to provide the requisite flair and train. In a number of instances there may be a patti, cut on the bias, varying between 4 and 12 inches approximately, added as a continuous border at the bottom. This border, all around the circumference, is not only for decorative purposes but also provides the requisite weight for the whole garment to drape or ‘fall’ in place (not very dissimilar in principle to the sari fall)

These took the form of wedding dresses made in elaborate pote and kimkhwab fabric, with our without zari wires, and a variety of embellishments in zardozi, salma, dabka, sequins and karchob work etc. The ones meant for occasional wear made in embossed, textured, handwoven silks, while plain cotton ones for everyday wear were made in cotton cheent (small prints in bright colours) or white muslin to brave the brutal Subcontinental summer.

Ghararas are what became de rigueur in the 1940s and 1950s as occasional/formal wear together with saris.

And so the elaborate farshis were confined to heirloom trunks.