Stay home if you are claustrophobic. At the gate several cars are lined and a steady stream of people enters after having their identity checked. Inside, pedestrians and commuters have gathered— a din of voices, hum of ceiling fans and a buzz from the fluorescent lights hangs over their heads. Seats are all taken and there is standing room only. People concentrate around various tables, arguing with the attendants, pleading; they want to be let inside the shut doors before anyone else. Others sit with a grim, dejected look on their faces. The calm confidence and the attire of yet others tells you that they are okay, that they will be taken care of; they are ushered into the shut doors before anyone else. A man cuts through the crowd, selling newspapers. Will another follow him with a tray of samosas and tea? A wall clock presides over all with callous indifference.

I wouldn’t blame you if you thought that I have described a railway station but in fact it is a hospital I’m talking about, a private one. Staying home is not an option and to the doctor’s office we must proceed. Fortunately, I have not had to go to a public hospital for treatment where majority of Pakistanis go to test their fates and see if their prayers of better health would be answered at the hands of an overworked, jaded and probably underpaid doctor. In fact, most of my hospital experience has been in Washington DC where I have spent most of my life. Much of my knowledge of hospitals in Pakistan has come from accompanying my parents or other family members to see the doctor. And so I have the unhappy disposition to compare and contrast and a need, as a writer, to try to tell the unpleasant truth.

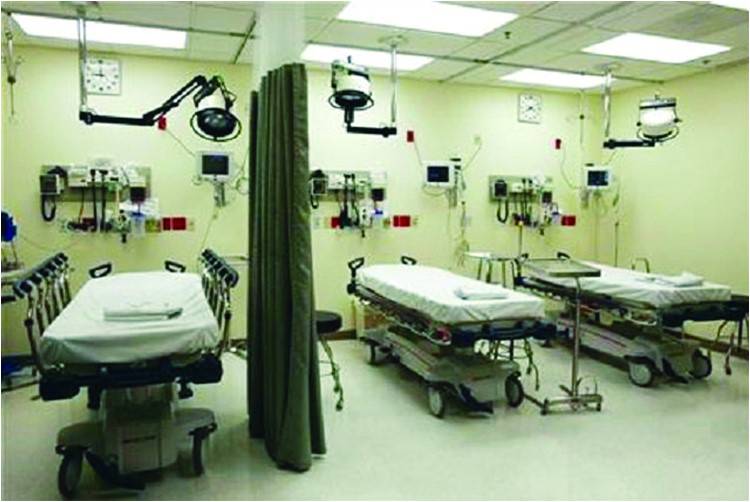

These are, as can be expected, two very different worlds and two divergent ways of treating patients. In the United States, if it is your first visit to the doctor, you are given forms, to be filled out after you check in, designed to take a detailed medical history. Forms ask you to list any medications being taken, allergies to any medications, previous surgeries; information is collected about family history of major illnesses. In addition, a number of conditions are specifically asked about, including heart disease. These forms are placed in a bin outside the examination room. Your height, weight and blood pressure are measured before you are shown into the same room once the doctor is ready to see you. In the meeting, the doctor conducts a detailed interview. In addition to discussing in detail your own medical conditions, the doctor asks about history of illnesses in the family, especially that of your parents, for you are more likely to develop any conditions your parents may have or are prevalent in the family. Information is stored in the hospital’s computer system, which you can access online, precluding the need to maintain your own file that you carry to the doctor’s office each time.

Several years ago my doctor started me on a statin when my cholesterol was found to be on the higher side. A few months later when my cholesterol fell to normal limits I asked him if I could discontinue the pill. He said to continue taking it indefinitely. Among the reasons he cited was a history of smoking in my South Asian origins; studies have shown that South Asians are genetically at a higher risk of heart disease, a fact that not many seem to be aware of and I have not heard a doctor stress its importance.

Here, in Pakistan, the visit to the doctor takes a different course. First, there aren’t any forms to fill out before you see the doctor, and there aren’t any separate examining rooms. You see the doctor in his office and often you are not alone, other patients sit on the couches while you talk to the doctor. It is not unusual for the doctor to attend to a phone call or two or sign a document brought in by the assistant. It is hard to discuss anything in private and the time that a physician spends with you is about as long as it takes him to scribble down in mysterious handwriting a list of pills that you must start popping. Not much explanation is given about the prognosis and the course of action, and you can scarcely ask any questions, there isn’t enough time.

It may seem easy to blame the doctor for not giving the patient proper attention, and there is blame to be appointed to him, but perhaps we should spare a thought for the overworked physician too. He has too many patients to see. The system teaches him to churn them out of his office like washers from a factory. Inevitably under-qualified physicians are promoted through the system to meet the demand. To see that the population pressure affects adversely every facet of life in Pakistan you just have to step out of your house. Roads, markets, shops, government offices, bus stations and hospitals are all clogged with people— there are simply too many of us. Even if the government takes effective measures to curtail population growth rate now, it will take years before it stabilizes. Combine this with the resource scarcity as a result of climate change that Pakistan is particularly vulnerable to, and we can see that we are headed straight for a cataclysmic catastrophe.

The neglect and underdevelopment that results from the perpetual tussle for power at the top of our society extracts a terrible price from an average Pakistani.

I wouldn’t blame you if you thought that I have described a railway station but in fact it is a hospital I’m talking about, a private one. Staying home is not an option and to the doctor’s office we must proceed. Fortunately, I have not had to go to a public hospital for treatment where majority of Pakistanis go to test their fates and see if their prayers of better health would be answered at the hands of an overworked, jaded and probably underpaid doctor. In fact, most of my hospital experience has been in Washington DC where I have spent most of my life. Much of my knowledge of hospitals in Pakistan has come from accompanying my parents or other family members to see the doctor. And so I have the unhappy disposition to compare and contrast and a need, as a writer, to try to tell the unpleasant truth.

Studies have shown that South Asians are genetically at a higher risk of heart disease, a fact not many seem to be aware of

These are, as can be expected, two very different worlds and two divergent ways of treating patients. In the United States, if it is your first visit to the doctor, you are given forms, to be filled out after you check in, designed to take a detailed medical history. Forms ask you to list any medications being taken, allergies to any medications, previous surgeries; information is collected about family history of major illnesses. In addition, a number of conditions are specifically asked about, including heart disease. These forms are placed in a bin outside the examination room. Your height, weight and blood pressure are measured before you are shown into the same room once the doctor is ready to see you. In the meeting, the doctor conducts a detailed interview. In addition to discussing in detail your own medical conditions, the doctor asks about history of illnesses in the family, especially that of your parents, for you are more likely to develop any conditions your parents may have or are prevalent in the family. Information is stored in the hospital’s computer system, which you can access online, precluding the need to maintain your own file that you carry to the doctor’s office each time.

Several years ago my doctor started me on a statin when my cholesterol was found to be on the higher side. A few months later when my cholesterol fell to normal limits I asked him if I could discontinue the pill. He said to continue taking it indefinitely. Among the reasons he cited was a history of smoking in my South Asian origins; studies have shown that South Asians are genetically at a higher risk of heart disease, a fact that not many seem to be aware of and I have not heard a doctor stress its importance.

Here, in Pakistan, the visit to the doctor takes a different course. First, there aren’t any forms to fill out before you see the doctor, and there aren’t any separate examining rooms. You see the doctor in his office and often you are not alone, other patients sit on the couches while you talk to the doctor. It is not unusual for the doctor to attend to a phone call or two or sign a document brought in by the assistant. It is hard to discuss anything in private and the time that a physician spends with you is about as long as it takes him to scribble down in mysterious handwriting a list of pills that you must start popping. Not much explanation is given about the prognosis and the course of action, and you can scarcely ask any questions, there isn’t enough time.

It may seem easy to blame the doctor for not giving the patient proper attention, and there is blame to be appointed to him, but perhaps we should spare a thought for the overworked physician too. He has too many patients to see. The system teaches him to churn them out of his office like washers from a factory. Inevitably under-qualified physicians are promoted through the system to meet the demand. To see that the population pressure affects adversely every facet of life in Pakistan you just have to step out of your house. Roads, markets, shops, government offices, bus stations and hospitals are all clogged with people— there are simply too many of us. Even if the government takes effective measures to curtail population growth rate now, it will take years before it stabilizes. Combine this with the resource scarcity as a result of climate change that Pakistan is particularly vulnerable to, and we can see that we are headed straight for a cataclysmic catastrophe.

The neglect and underdevelopment that results from the perpetual tussle for power at the top of our society extracts a terrible price from an average Pakistani.