Having spent almost my entire adult life in Karachi, I regard myself as an Old Karachi-ite. Yes, I do remember the good days when both Karachi and I were considerably younger. And I remember those days happily because…well, I was, as I said, young, and I was discovering the joys (and the pains) of being alive and of being free to make my own choices.

So, was Karachi a happier city then than it is now? That is what many of my WhatsApp friends say. They contend that today’s garbage-choked, crime-ridden urban nightmare, where violence lurks around every corner, was once a haven of peace and tolerance. As evidence, they point to the former happy coexistence of mosques alongside churches - and both of these alongside bars, nightclubs and suchlike.

But, readers, let’s get real. Perhaps we do miss the thaalis at Pioneer Coffee House, or the samosas at Frederick’s Cafeteria, or the watered-down drinks and Lebanese girls at the Roma Shabana; but this is mere nostalgia. A friendly and welcoming city, Karachi may have been (so, as history tells us, are all big cities everywhere in the world); a peaceful city, it was not.

From bar-room brawls to muggings in the notorious neighbourhood of the Bulbul-e-Hazar Dastaan building, to student riots, labour Gherao-Jalaos, language riots, and the trope about the stone-throwing Lalukhet culture: we had them all. And then some. The fact that youngsters like us dared (as we now boast) to risk the meanest of the mean streets at 4:00 am, in order to drink karrak chai at some especially grimy dhabba, is because we were young. And, yes, we did regard the dark, deserted gallies as daring territory to enter, and therefore something of a challenge.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I did think Karachi a great place, which is why I chose to live here rather than in my town of birth. This was not because Karachi was some leafy island of law-abiding peace, but because it was big and bright and thrumming with vitality.

But two destructive processes were at work here, which would soon put paid to that brightness and that vitality.

The first of these was a sociological inevitability. To understand this, consider an experiment performed (I think, in the then Soviet Union) in the early 1960s. A community of rats was put into what was a reasonably pleasant environment by rat standards. Over a period, more and more rats were added into those already in the environment although food supplies remained adequate.

Now, in the early stages of this experiment, the rats had their usual quota of internal fights, over morsels of food or mating rights or status privileges. But, as the overcrowding of their environment grew worse, their fights became more and more frequent, and more and more violent.

After a certain stage, the scientists observed the outbreak of serious psychotic behaviour in many of the rats. Some of them became catatonically depressive, sitting in one place and trembling, neither eating nor sleeping. Some others became more clearly suicidal, even bizarrely chewing off their own tails and paws. And a few became killers, who would go around murdering other rats until they were murdered themselves. My readers should note that rats, like most other higher animals - but unlike humans - do not deliberately kill members of their own species. Thus, this was un-ratlike, aberrant behaviour.

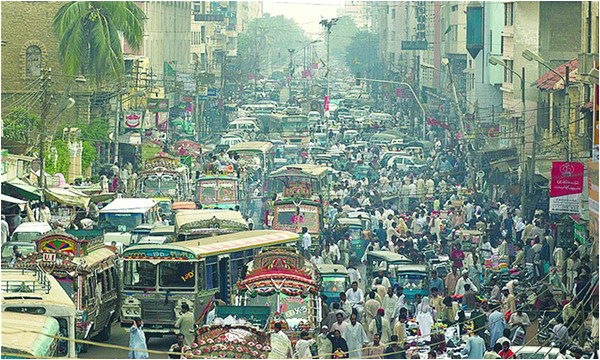

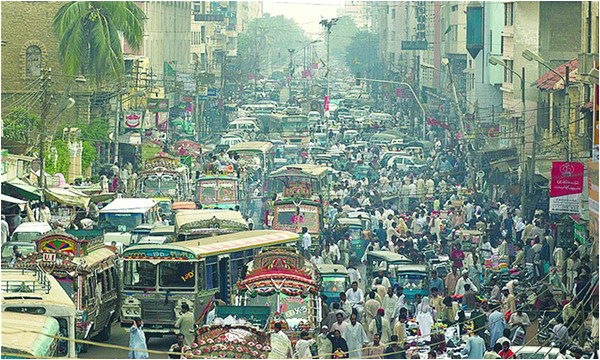

Now, turn to Karachi. With a population somewhere well above twenty million (you can ignore those nonsensical census results), it is certainly a classic case of grossly excessive urban bloating. In Mohammed Hanif’s novel Our Lady of Alice Bhatti, one of his characters observes: “Do they want a post-mortem? No. Are they interested in the cause of death? No. Does it really matter to them if their lungs gave up first or their heart went pachuk? For them the cause of death is death. For them they died because death arrived in Garden East and they happened to be buying vegetables there.”

Does my reader note that? Death “arrived in Garden East (when people) happened to be buying vegetables there”. A cold, emotionless force. No passion, no need, no greed, no hatred. Just cold-blooded killing!

Am I suggesting that the Karachi killers are, like some of the Soviet rats, psychotic? Yes, they are, even if they wrap their psychotic hatreds in ethnic and sectarian narratives. It is a psychological abnormality, an extreme one, to wish to take the life of some stranger, from whom you want nothing, whom you do not hate nor love nor even know. Such passionless, impersonal murders are committed by those whose souls are empty and whose minds have been distorted by psychosis. Given that such psychoses already exist, as a result of urban overcrowding, the massive induction of firearms into uncontrolled hands opened the way to civic collapse.

Let us now travel to our north, where, as a result of the 1978 CIA-inspired war in Afghanistan against the then USSR, over three million families fled their homes in that country and took shelter in Pakistan, many finding their way to Karachi. Here, they were crowded into squalid refugee camps or ended up in filthy shanty towns. Cut off from their organic roots to their soil, their villages, and their traditional institutions, these people became sad, hopeless wanderers in a foreign land. Consider the dreadful isolation and sense of alienation of which these Afghan refugees were victims. Think of it, dear reader, and tremble.

Hearts numbed and souls emptied, some among them were easy prey for those who cynically sought to fill their minds with hatred and bigotry. The Muslim values and tribal traditions of these refugees were perversely exploited to turn some of them into mindless killing machines. The process was systematic and thorough and no device was left un-utilized. Once their hearts had been sufficiently numbed and their minds thoroughly distorted, they were supplied with guns, grenades, rocket launchers, and ammunition and were given training in their use.

Now, whatever the worth or otherwise of the so-called Mujahideen and their Taliban successors, my concern here is with the blowback of their war – the longest war in history since the 14th century. To the ethnic/sectarian sniper and the perforating electric-drill operator was now added the suicide bomber. This further practitioner of death demonstrated his presence among us with the Imambargah attack in 1985 and the Bohri Bazaar bombings in 1987. After that, the path has been downhill…with bombs going off with horrific frequency in Karachi and everywhere else.

Thus, from the 1960s and 1970s, Karachi descended quickly to a free-fire hell by the 1980s and 1990s. The face that looms behind both the destructive processes we have been considering is the same one: that of the general with the comedian’s moustache and cold, executioner’s eyes, who illegitimately seized power in 1977. His malign legacy remains with us everywhere.

Yes, much has improved since the fates swatted his plane down from the sky. But have we learned our lessons yet?

So, was Karachi a happier city then than it is now? That is what many of my WhatsApp friends say. They contend that today’s garbage-choked, crime-ridden urban nightmare, where violence lurks around every corner, was once a haven of peace and tolerance. As evidence, they point to the former happy coexistence of mosques alongside churches - and both of these alongside bars, nightclubs and suchlike.

But, readers, let’s get real. Perhaps we do miss the thaalis at Pioneer Coffee House, or the samosas at Frederick’s Cafeteria, or the watered-down drinks and Lebanese girls at the Roma Shabana; but this is mere nostalgia. A friendly and welcoming city, Karachi may have been (so, as history tells us, are all big cities everywhere in the world); a peaceful city, it was not.

From bar-room brawls to muggings in the notorious neighbourhood of the Bulbul-e-Hazar Dastaan building, to student riots, labour Gherao-Jalaos, language riots, and the trope about the stone-throwing Lalukhet culture: we had them all. And then some. The fact that youngsters like us dared (as we now boast) to risk the meanest of the mean streets at 4:00 am, in order to drink karrak chai at some especially grimy dhabba, is because we were young. And, yes, we did regard the dark, deserted gallies as daring territory to enter, and therefore something of a challenge.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I did think Karachi a great place, which is why I chose to live here rather than in my town of birth. This was not because Karachi was some leafy island of law-abiding peace, but because it was big and bright and thrumming with vitality.

But two destructive processes were at work here, which would soon put paid to that brightness and that vitality.

The first of these was a sociological inevitability. To understand this, consider an experiment performed (I think, in the then Soviet Union) in the early 1960s. A community of rats was put into what was a reasonably pleasant environment by rat standards. Over a period, more and more rats were added into those already in the environment although food supplies remained adequate.

The fact that youngsters like us dared (as we now boast) to risk the meanest of the mean streets at 4:00 am, in order to drink karrak chai at some especially grimy dhabba, is because we were young

Now, in the early stages of this experiment, the rats had their usual quota of internal fights, over morsels of food or mating rights or status privileges. But, as the overcrowding of their environment grew worse, their fights became more and more frequent, and more and more violent.

After a certain stage, the scientists observed the outbreak of serious psychotic behaviour in many of the rats. Some of them became catatonically depressive, sitting in one place and trembling, neither eating nor sleeping. Some others became more clearly suicidal, even bizarrely chewing off their own tails and paws. And a few became killers, who would go around murdering other rats until they were murdered themselves. My readers should note that rats, like most other higher animals - but unlike humans - do not deliberately kill members of their own species. Thus, this was un-ratlike, aberrant behaviour.

Now, turn to Karachi. With a population somewhere well above twenty million (you can ignore those nonsensical census results), it is certainly a classic case of grossly excessive urban bloating. In Mohammed Hanif’s novel Our Lady of Alice Bhatti, one of his characters observes: “Do they want a post-mortem? No. Are they interested in the cause of death? No. Does it really matter to them if their lungs gave up first or their heart went pachuk? For them the cause of death is death. For them they died because death arrived in Garden East and they happened to be buying vegetables there.”

Does my reader note that? Death “arrived in Garden East (when people) happened to be buying vegetables there”. A cold, emotionless force. No passion, no need, no greed, no hatred. Just cold-blooded killing!

Am I suggesting that the Karachi killers are, like some of the Soviet rats, psychotic? Yes, they are, even if they wrap their psychotic hatreds in ethnic and sectarian narratives. It is a psychological abnormality, an extreme one, to wish to take the life of some stranger, from whom you want nothing, whom you do not hate nor love nor even know. Such passionless, impersonal murders are committed by those whose souls are empty and whose minds have been distorted by psychosis. Given that such psychoses already exist, as a result of urban overcrowding, the massive induction of firearms into uncontrolled hands opened the way to civic collapse.

Let us now travel to our north, where, as a result of the 1978 CIA-inspired war in Afghanistan against the then USSR, over three million families fled their homes in that country and took shelter in Pakistan, many finding their way to Karachi. Here, they were crowded into squalid refugee camps or ended up in filthy shanty towns. Cut off from their organic roots to their soil, their villages, and their traditional institutions, these people became sad, hopeless wanderers in a foreign land. Consider the dreadful isolation and sense of alienation of which these Afghan refugees were victims. Think of it, dear reader, and tremble.

Hearts numbed and souls emptied, some among them were easy prey for those who cynically sought to fill their minds with hatred and bigotry. The Muslim values and tribal traditions of these refugees were perversely exploited to turn some of them into mindless killing machines. The process was systematic and thorough and no device was left un-utilized. Once their hearts had been sufficiently numbed and their minds thoroughly distorted, they were supplied with guns, grenades, rocket launchers, and ammunition and were given training in their use.

Now, whatever the worth or otherwise of the so-called Mujahideen and their Taliban successors, my concern here is with the blowback of their war – the longest war in history since the 14th century. To the ethnic/sectarian sniper and the perforating electric-drill operator was now added the suicide bomber. This further practitioner of death demonstrated his presence among us with the Imambargah attack in 1985 and the Bohri Bazaar bombings in 1987. After that, the path has been downhill…with bombs going off with horrific frequency in Karachi and everywhere else.

Thus, from the 1960s and 1970s, Karachi descended quickly to a free-fire hell by the 1980s and 1990s. The face that looms behind both the destructive processes we have been considering is the same one: that of the general with the comedian’s moustache and cold, executioner’s eyes, who illegitimately seized power in 1977. His malign legacy remains with us everywhere.

Yes, much has improved since the fates swatted his plane down from the sky. But have we learned our lessons yet?