Since Osama bin Laden’s capture from his compound in Abbotabad in May 2011, when a team of US special forces flew 120 miles into Pakistani territory from their base in Afghanistan, there has been a sentiment in India that if the Americans can violate Pakistani sovereignty to act against a terrorist, so can the Indians.

In the aftermath of the recent suicide attack on Indian security personnel in Pulwama, Modi’s government put that theory to test by sending in its air force to bomb an alleged Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM) facility in Balakot, as India believed that the Kashmiri suicide bomber, Adil Dar, was backed by JeM in Pakistan. For the first time since 1971, India ventured into Pakistan proper, beyond skirmishes at the line of control. The message was clear: India was willing to cross a previous red line and violate Pakistan’s territorial integrity. India claimed that its fight was neither with the Pakistani people, nor the military but with the terrorists operating from Pakistani soil.

If Pakistan had not responded to this act of aggression from India, questions would have been raised both domestically and internationally about the ability of its armed forces to defend Pakistani territory in the event of war. Pakistan Air Force performed brilliantly. The very next day, Pakistani pilots entered Indian airspace, locked in on targets but did not fire, engaged Indian pilots in a dogfight that resulted in Indian planes being shot down and captured an Indian Wing Commander.

Though both sides managed to avoid civilian casualties, it turns out that India is unable to provide proof of the hundreds of militants it claimed to have killed, suggesting that the Indian Air Force may have missed its target altogether and ending up destroying trees instead.

This is a clear military win for Pakistan. Yet Prime Minister Imran Khan extended a hand of peace. As the civilian face of the government, he offered talks with the Modi government. This was a good idea, but Modi was in no mood to talk. So instead of waiting for Modi to “take one step forward, so he [Imran Khan] could take two,” as he had famously said in his victory speech, the prime minister took several steps unilaterally and promptly released the captive Indian pilot Abhinandan. The wisdom of this move is questionable, given that it did not lead to any assurance of peace from the other side.

International press praised the move as another peace overture, but it did not result in any guarantees from powerful foreign governments, whether western or Arab, that India would engage in constructive dialogue with Pakistan, which is really the need of the hour in order for two nuclear powers to avoid war at all cost. Moreover, both the Europeans and Americans have urged Imran Khan to take action against terror groups, without mentioning that India should address the grave problem in Kashmir.

Why does the world tilt towards India’s position more than ours? Perhaps it is time to address this rationally without playing the victim card. Sure, it could have something to do with the fact that India is a bigger economy and that the West is looking to India to contain China, but that alone does not explain it. There are other factors too. India’s narrative of terrorists trained in Pakistan attacking the Indian parliament in 2001, Mumbai in 2008, an army camp in Uri and Pathankot Air Force base in 2016 resonates abroad, particularly when India claims that in the aftermath of these attacks it showed restraint and did not wage war on Pakistan - with the exception of “surgical strikes” along the Line of Control in 2016.

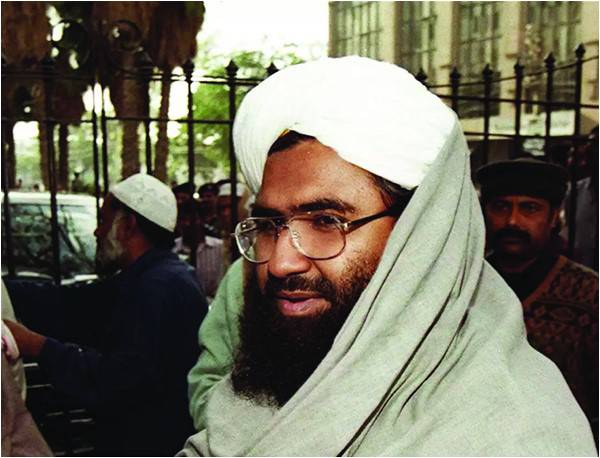

India is not the only country that blames Pakistan for cross-border terrorism. Similar allegations have been made by the US, Afghanistan, and more recently, Iran. This should give Pakistan pause. A claim that is repeated by so many voices internationally is bound to get traction. Pakistan can have the best diplomats working for it but the world will still ask if it is willing to take action against the likes of Masood Azhar.

It may seem unfair that questions are not asked by global powers of India for all the state terrorism it perpetuates in Kashmir. But here is a thought: does harbouring terrorists help Kashmir in any way? It may harm India and its soldiers but does it help Kashmiris? More importantly, has it helped Pakistanis? Haven’t these groups also turned on us, attacking our schools, bazaars and even security forces within Pakistan? Aren’t they the cause of Pakistan being placed on financial watch-lists, which our fragile economy can ill-afford?

It is easy to pin the war-mongering on a hysterical Indian media and Modi’s upcoming election but we should not lose sight of the terrorism problem that has brought us to this precipice. It is something the world has been talking about for over a decade now. Sometimes it seems like there is a realisation in Pakistan to tackle this problem, but then priorities are muddled and the nation once again distracted.

The world appreciates a strong military. It does not appreciate jihadi proxies. If Pakistan wishes to bolster its image globally, it must dismantle terror networks. In order to do this, the state requires a clear vision and must understand that it needs as much support as it can get. It cannot, therefore, be hounding and disrespecting political opponents and simultaneously expect to make headway on this existential threat.

The current government is lucky that the opposition is mature. One must recall that Imran Khan’s own role as an opposition figure on this matter was highly dubious, particularly when the “Dawn Leaks” hoax was created and those trying to address this central issue and achieve peace with India were characterised as traitors. Nevertheless, if Imran Khan is going to take a U-turn on his previous position with regards to this issue, we can welcome it this time.

The prime minister should always be cognisant of the fact that the world appreciates a democracy over an authoritarian regime. For many years, India had established its credentials as a robust democracy, more open to free thought and more secular than Pakistan. Certainly, India is currently in a downward slide. Modi is taking it down the path of ultra-nationalism and religious bigotry, where dissenters are accused of being Pakistan-lovers.

If we really want to improve our image in the world and capitalise on the good press Pakistan has gotten in trying to de-escalate the recent armed conflict with India, we must adopt the opposite approach. We must tolerate dissent and not stifle it. We must hear all sides, even if we don’t agree with them. We should unite our people by giving them freedom and rights, and not push unity down their throats or threaten them with treason. We should be accepting, not only of all shades of politics and politicians but also of all religions. If Fayyazul Hassan Chohan, as the Punjab information minister, can disparage Hindus, then how can we claim to be better than those who insult Muslims in India?

The writer is a lawyer based in London

In the aftermath of the recent suicide attack on Indian security personnel in Pulwama, Modi’s government put that theory to test by sending in its air force to bomb an alleged Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM) facility in Balakot, as India believed that the Kashmiri suicide bomber, Adil Dar, was backed by JeM in Pakistan. For the first time since 1971, India ventured into Pakistan proper, beyond skirmishes at the line of control. The message was clear: India was willing to cross a previous red line and violate Pakistan’s territorial integrity. India claimed that its fight was neither with the Pakistani people, nor the military but with the terrorists operating from Pakistani soil.

If Pakistan had not responded to this act of aggression from India, questions would have been raised both domestically and internationally about the ability of its armed forces to defend Pakistani territory in the event of war. Pakistan Air Force performed brilliantly. The very next day, Pakistani pilots entered Indian airspace, locked in on targets but did not fire, engaged Indian pilots in a dogfight that resulted in Indian planes being shot down and captured an Indian Wing Commander.

Though both sides managed to avoid civilian casualties, it turns out that India is unable to provide proof of the hundreds of militants it claimed to have killed, suggesting that the Indian Air Force may have missed its target altogether and ending up destroying trees instead.

India is not the only country that blames Pakistan for cross-border terrorism. Similar allegations have been made by the US, Afghanistan, and more recently, Iran

This is a clear military win for Pakistan. Yet Prime Minister Imran Khan extended a hand of peace. As the civilian face of the government, he offered talks with the Modi government. This was a good idea, but Modi was in no mood to talk. So instead of waiting for Modi to “take one step forward, so he [Imran Khan] could take two,” as he had famously said in his victory speech, the prime minister took several steps unilaterally and promptly released the captive Indian pilot Abhinandan. The wisdom of this move is questionable, given that it did not lead to any assurance of peace from the other side.

International press praised the move as another peace overture, but it did not result in any guarantees from powerful foreign governments, whether western or Arab, that India would engage in constructive dialogue with Pakistan, which is really the need of the hour in order for two nuclear powers to avoid war at all cost. Moreover, both the Europeans and Americans have urged Imran Khan to take action against terror groups, without mentioning that India should address the grave problem in Kashmir.

Why does the world tilt towards India’s position more than ours? Perhaps it is time to address this rationally without playing the victim card. Sure, it could have something to do with the fact that India is a bigger economy and that the West is looking to India to contain China, but that alone does not explain it. There are other factors too. India’s narrative of terrorists trained in Pakistan attacking the Indian parliament in 2001, Mumbai in 2008, an army camp in Uri and Pathankot Air Force base in 2016 resonates abroad, particularly when India claims that in the aftermath of these attacks it showed restraint and did not wage war on Pakistan - with the exception of “surgical strikes” along the Line of Control in 2016.

India is not the only country that blames Pakistan for cross-border terrorism. Similar allegations have been made by the US, Afghanistan, and more recently, Iran. This should give Pakistan pause. A claim that is repeated by so many voices internationally is bound to get traction. Pakistan can have the best diplomats working for it but the world will still ask if it is willing to take action against the likes of Masood Azhar.

It may seem unfair that questions are not asked by global powers of India for all the state terrorism it perpetuates in Kashmir. But here is a thought: does harbouring terrorists help Kashmir in any way? It may harm India and its soldiers but does it help Kashmiris? More importantly, has it helped Pakistanis? Haven’t these groups also turned on us, attacking our schools, bazaars and even security forces within Pakistan? Aren’t they the cause of Pakistan being placed on financial watch-lists, which our fragile economy can ill-afford?

It is easy to pin the war-mongering on a hysterical Indian media and Modi’s upcoming election but we should not lose sight of the terrorism problem that has brought us to this precipice. It is something the world has been talking about for over a decade now. Sometimes it seems like there is a realisation in Pakistan to tackle this problem, but then priorities are muddled and the nation once again distracted.

The world appreciates a strong military. It does not appreciate jihadi proxies. If Pakistan wishes to bolster its image globally, it must dismantle terror networks. In order to do this, the state requires a clear vision and must understand that it needs as much support as it can get. It cannot, therefore, be hounding and disrespecting political opponents and simultaneously expect to make headway on this existential threat.

The current government is lucky that the opposition is mature. One must recall that Imran Khan’s own role as an opposition figure on this matter was highly dubious, particularly when the “Dawn Leaks” hoax was created and those trying to address this central issue and achieve peace with India were characterised as traitors. Nevertheless, if Imran Khan is going to take a U-turn on his previous position with regards to this issue, we can welcome it this time.

The prime minister should always be cognisant of the fact that the world appreciates a democracy over an authoritarian regime. For many years, India had established its credentials as a robust democracy, more open to free thought and more secular than Pakistan. Certainly, India is currently in a downward slide. Modi is taking it down the path of ultra-nationalism and religious bigotry, where dissenters are accused of being Pakistan-lovers.

If we really want to improve our image in the world and capitalise on the good press Pakistan has gotten in trying to de-escalate the recent armed conflict with India, we must adopt the opposite approach. We must tolerate dissent and not stifle it. We must hear all sides, even if we don’t agree with them. We should unite our people by giving them freedom and rights, and not push unity down their throats or threaten them with treason. We should be accepting, not only of all shades of politics and politicians but also of all religions. If Fayyazul Hassan Chohan, as the Punjab information minister, can disparage Hindus, then how can we claim to be better than those who insult Muslims in India?

The writer is a lawyer based in London