The writings produced by a community are invaluable assets for it. They help in preserving its identity, advancing its thinking and inspiring it to struggle. These writings carry with them the experiences of numerous lives and ideas of many great minds. While oral tradition is indeed an important mode of transmission, perhaps no one would disagree that writings are generally more reliable and long-lasting. Precisely for this reason, humans have been writing since ages. Civilized societies have been making efforts to preserve such writings and, in general, big libraries may safely be relied upon as a reflection of the intellect of a people.

By contrast, the abandonment of these libraries would reflect the downfall of these societies. When the ancient library at Alexandria in Egypt was burned down, a whole chapter of history got closed for ever. When Muslim dynasties in Spain built around the culture of Cordoba and Granada started parting ways with their learning and scholarly works, their footprints in the Iberian Peninsula soon faded away in the aftermath of military defeats. When the Mongols, under Hulagu Khan, destroyed the libraries and learning institutes at Baghdad around the 13th century, the Abbasid Caliphate could never recover from such a blow. These incidents involved the loss of invaluable and irrecoverable writings and knowledge.

During the Indian Mutiny against the British in the 1857, a number of books were destroyed, educational institutions got closed and in the aftermath of the war, the British cracked down upon the Indian (especially Muslim) scholars and notables (deeming them as ‘rebels’). Thus, the already declining scholarship in India met with a major setback and Indians, especially the Muslims, underwent a profound regression. Gaining benefit from the decline of the Indian scholarship, the British found it easier to inculcate narratives that served colonial interests better into the minds of the ‘educated’ Indians. Not only did this enable prolongation of their colonial rule, many of its effects continue to resonate till this day.

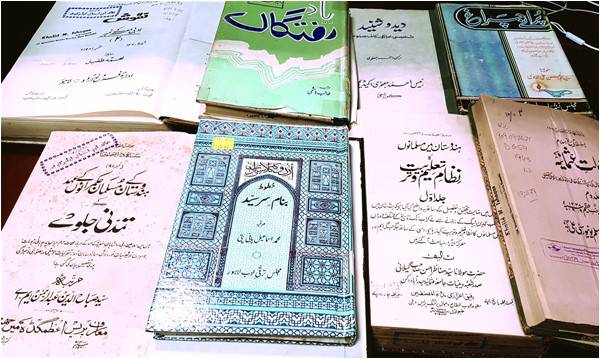

In view of all this, it is deeply painful to see an ever declining trend in buying, publishing, keeping and reading of books in Pakistan – even though this is actually part of a global phenomenon. As newer technology is arising to make the lives of humans ‘comfortable’, fewer people are willing to leave their ‘comfort zone’. Many spend lavishly to get ‘comfort’ and ‘amusement’ but fewer spend on actually learning and improving themselves. People complain about poor circumstances but seldom strive to engage in intellectually productive activities which include reading and learning. Thus, it is ironic when some voices blame sections of society or ‘foreign conspirators’ for our ‘manifold issues’ while we are paving the path towards downfall ourselves!

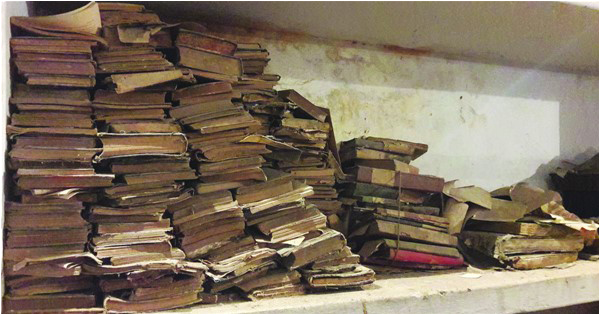

Apart from representing a disturbing trend in our thinking, priorities, objectives and, thus, intellectuality and productivity, this also means losing our heritage. As our history, ideas, culture and even languages are fading away with the writings and books that carry them, we are losing a great deal of information and knowledge. This could make our identities blurry and our thinking process more convoluted. Similarly, this allows ‘others’ to easily manipulate facts with fiction and in the absence of a reliable record – people will be prone to accepting it as ‘the truth’.

Recently, I was met with utter surprise when I found difficulty in finding a renowned Urdu poetry collection Kuliyat-e-Akbar (by Akbar Allahabadi) at Lahore’s Urdu Bazaar. Among the bookstores I visited in my vain quest was Al Faisal Publishers, the owner of which, Mr. Faisal, lamented that such books take years to sell out and so the publishers hesitate to produce them – while the bookstores have become reluctant to stock them. He also expressed resentment at the overall decline in book sales nowadays, particularly titles in Urdu. On another occasion, I was looking for Tareekh-e-Sindh by Syed Abu Zafar Nadwi in Karachi’s Urdu Bazaar. I was told that this book was published in Pakistan quite long ago but now I might be able to get it through someone from India (where it was published for the first time, probably a few days before the creation of Pakistan). I regretted the fact that a book on Sindh was likely to be found in India rather than in Pakistan, where Sindh is now actually located!

Another friend narrated that recently he wrote a book related to the Islamic tradition in Medicine – one that was appreciated by many publishers. But they excused themselves from publishing it because “Such books don’t sell nowadays.” ZamZam Publishers, a renowned publisher in Karachi (that mostly publishes Islamic books in Arabic, Urdu and English) mentioned that now they are compelled to publish primarily those books that are a part of the syllabi of schools and Madrassahs, since they are the ones that actually sell. These are the only works that allow publishers to make ends meet.

If the earlier writings are fading away and newer ones are finding hard time getting published, it goes without saying that the overall effect on society will be severely detrimental. Perhaps it is time that we reclaimed a culture of reading and learning. Buying books needs to be encouraged not only to read but also to support the writers and the publishers – so that they might continue contributing to society and make a living out of it.

As for preserving the older writings, perhaps a good initiative would be to digitalize those among them which are less feasible to be republished (without impinging any copyrights). This will require a much lesser investment than reprinting them while ensuring preservation and enabling a wider distribution.

Certain projects are already contributing greatly in this regard which include thousands of old Urdu books uploaded on Archive.org by the University of Toronto and the Indian Public Library, among others. Another large database for Urdu poetry, books and other related files is available on Rekhta.org – which was founded by a lover of Urdu from India, Sanjiv Saraf. Unfortunately, there doesn’t seem to by any such large-scale initiative in Pakistan, which claims more ‘right’ to Urdu language than other countries.

While handsome amounts are spent on saving our culture and heritage through preservation of historical sites, restoration of old buildings, establishment of museums, ‘cultural festivals’ and various other means, it is even more important to preserve our intellectual heritage –much of which is found in our writings. This requires efforts by the government, educational institutes, organizations and each individual.

The author studied medicine at Ziauddin University (Karachi) and can be contacted on Twitter at @drsyedtalhashah

By contrast, the abandonment of these libraries would reflect the downfall of these societies. When the ancient library at Alexandria in Egypt was burned down, a whole chapter of history got closed for ever. When Muslim dynasties in Spain built around the culture of Cordoba and Granada started parting ways with their learning and scholarly works, their footprints in the Iberian Peninsula soon faded away in the aftermath of military defeats. When the Mongols, under Hulagu Khan, destroyed the libraries and learning institutes at Baghdad around the 13th century, the Abbasid Caliphate could never recover from such a blow. These incidents involved the loss of invaluable and irrecoverable writings and knowledge.

During the Indian Mutiny against the British in the 1857, a number of books were destroyed, educational institutions got closed and in the aftermath of the war, the British cracked down upon the Indian (especially Muslim) scholars and notables (deeming them as ‘rebels’). Thus, the already declining scholarship in India met with a major setback and Indians, especially the Muslims, underwent a profound regression. Gaining benefit from the decline of the Indian scholarship, the British found it easier to inculcate narratives that served colonial interests better into the minds of the ‘educated’ Indians. Not only did this enable prolongation of their colonial rule, many of its effects continue to resonate till this day.

In view of all this, it is deeply painful to see an ever declining trend in buying, publishing, keeping and reading of books in Pakistan – even though this is actually part of a global phenomenon. As newer technology is arising to make the lives of humans ‘comfortable’, fewer people are willing to leave their ‘comfort zone’. Many spend lavishly to get ‘comfort’ and ‘amusement’ but fewer spend on actually learning and improving themselves. People complain about poor circumstances but seldom strive to engage in intellectually productive activities which include reading and learning. Thus, it is ironic when some voices blame sections of society or ‘foreign conspirators’ for our ‘manifold issues’ while we are paving the path towards downfall ourselves!

Apart from representing a disturbing trend in our thinking, priorities, objectives and, thus, intellectuality and productivity, this also means losing our heritage. As our history, ideas, culture and even languages are fading away with the writings and books that carry them, we are losing a great deal of information and knowledge. This could make our identities blurry and our thinking process more convoluted. Similarly, this allows ‘others’ to easily manipulate facts with fiction and in the absence of a reliable record – people will be prone to accepting it as ‘the truth’.

Recently, I was met with utter surprise when I found difficulty in finding a renowned Urdu poetry collection Kuliyat-e-Akbar (by Akbar Allahabadi) at Lahore’s Urdu Bazaar. Among the bookstores I visited in my vain quest was Al Faisal Publishers, the owner of which, Mr. Faisal, lamented that such books take years to sell out and so the publishers hesitate to produce them – while the bookstores have become reluctant to stock them. He also expressed resentment at the overall decline in book sales nowadays, particularly titles in Urdu. On another occasion, I was looking for Tareekh-e-Sindh by Syed Abu Zafar Nadwi in Karachi’s Urdu Bazaar. I was told that this book was published in Pakistan quite long ago but now I might be able to get it through someone from India (where it was published for the first time, probably a few days before the creation of Pakistan). I regretted the fact that a book on Sindh was likely to be found in India rather than in Pakistan, where Sindh is now actually located!

Another friend narrated that recently he wrote a book related to the Islamic tradition in Medicine – one that was appreciated by many publishers. But they excused themselves from publishing it because “Such books don’t sell nowadays.” ZamZam Publishers, a renowned publisher in Karachi (that mostly publishes Islamic books in Arabic, Urdu and English) mentioned that now they are compelled to publish primarily those books that are a part of the syllabi of schools and Madrassahs, since they are the ones that actually sell. These are the only works that allow publishers to make ends meet.

If the earlier writings are fading away and newer ones are finding hard time getting published, it goes without saying that the overall effect on society will be severely detrimental. Perhaps it is time that we reclaimed a culture of reading and learning. Buying books needs to be encouraged not only to read but also to support the writers and the publishers – so that they might continue contributing to society and make a living out of it.

As for preserving the older writings, perhaps a good initiative would be to digitalize those among them which are less feasible to be republished (without impinging any copyrights). This will require a much lesser investment than reprinting them while ensuring preservation and enabling a wider distribution.

Certain projects are already contributing greatly in this regard which include thousands of old Urdu books uploaded on Archive.org by the University of Toronto and the Indian Public Library, among others. Another large database for Urdu poetry, books and other related files is available on Rekhta.org – which was founded by a lover of Urdu from India, Sanjiv Saraf. Unfortunately, there doesn’t seem to by any such large-scale initiative in Pakistan, which claims more ‘right’ to Urdu language than other countries.

While handsome amounts are spent on saving our culture and heritage through preservation of historical sites, restoration of old buildings, establishment of museums, ‘cultural festivals’ and various other means, it is even more important to preserve our intellectual heritage –much of which is found in our writings. This requires efforts by the government, educational institutes, organizations and each individual.

The author studied medicine at Ziauddin University (Karachi) and can be contacted on Twitter at @drsyedtalhashah