Mary Oliver, the Pulitzer winning poet, died in the US last week. The resulting obituaries were full of her observations, particularly on how she lived her life. “Still, what I want in my life is to be willing to be dazzled,” she wrote in The Ponds, “— to cast aside the weight of facts and maybe even to float a little above this difficult world.”

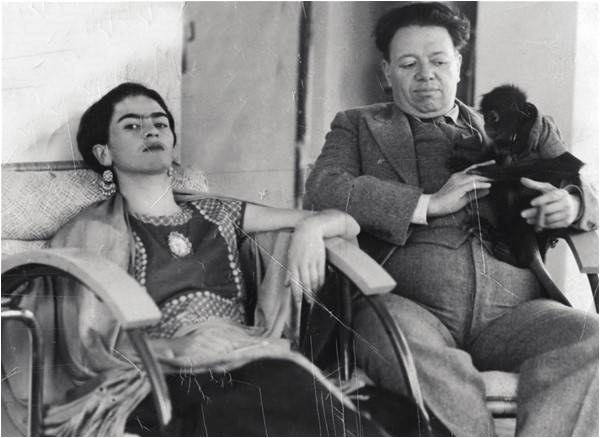

Never did I understand the meaning of the word ‘dazzled’ better than after visiting the home of the Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, whose spectacular work justifies her reputation in Mexico. There, she has become a symbol, larger than life and at a par with her fiery artist husband Diego Rivera.

As a Pakistani, I empathize instinctively with Mexico. It carries the same sort of stigma in the international consciousness – a knee-jerk association with guns, drugs, lawlessness and furtive, oiled immigrants.

Mexico City is a beautiful surprise: leafy green squares and public spaces, a mixture of high-rise buildings with old haciendas nestling at their feet, the frenetic rush hour of commuters scurrying to work, stopping even in their urgency for a hurried snack at the informal food stalls which serve fresh corn tortillas with fried eggs and a hint of fresh jalapeno. One can see entrepreneurial energy sprouting out of every pavement. Who says a thriving start-up culture can be found only in California?

After meetings in the Coyoacan district, colleagues pointed out that we were in the same district as Frida Kahlo’s house – now a museum and the most visited site in Mexico City. It was one of those quick decisions that happen when one travels, but in retrospect, end up becoming the incredible experience that defines the trip.

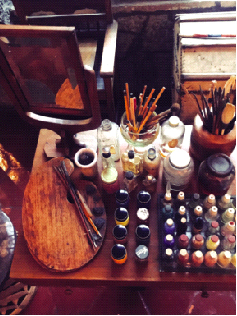

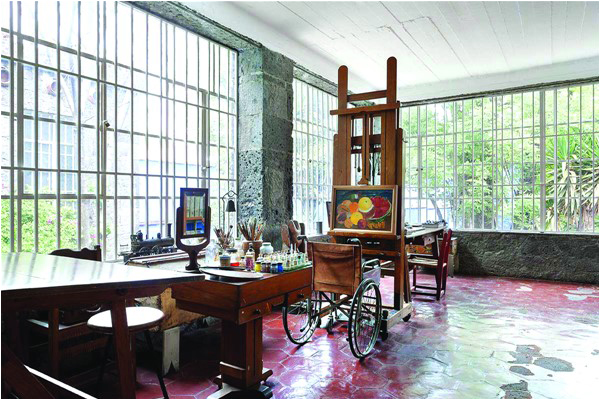

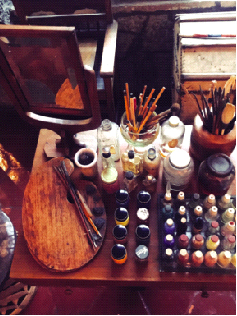

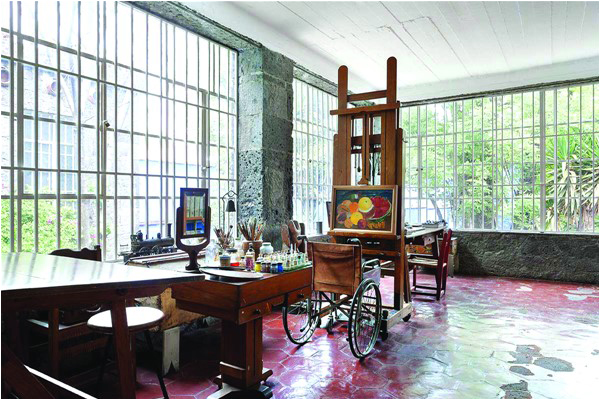

Houses often assume the personalities of their occupants. Some are happy,others soulless. In many houses, one is no longer aware of the identity of those who once inhabited them. This is not the case In Casa Azul. Everything – her desk, her studio with jars of paints and her fiery paintings themselves – lay scattered about, just as if she were still alive.

Frida’s house is set in an area surrounded by other homes, but distinguishable from them by its bright azure blue and the spectrum of Mexico’s natural palette. Stucco pillars support the tiled roof which covered walkways between the house and its outer chambers, all built around a series of small courtyards. Rows of palm trees are planted alongside terracotta planters. When she was alive, peacocks used to run loose in the garden, providing their own splash of vivid colour.

It was in this house that Frida was born to a German-Jewish father and a native Mexican mother. Her father experimented with photography and as one wanders though the house, one can see the impact of his experimentation. As a child, Frida would accompany him to his dark room – partly to keep an eye on him in case he suffered an epileptic episode.

She grew up in the various courtyards, running around under the cactus trees. At the age of six, she suffered a polio attack. Another debilitating accident at age eighteen left her with a crushed spine. Years of operations meant she was in physical pain for the rest of her life. These setbacks did little to slow down her determination to enjoy life, nor did they dampen her artistic flair. She lived life beyond life itself, as only artists can – goaded but not subdued by suffering and pain.

Walking through her home, one gets a strong sense of the presence of her spirit – the creativity that erupts in so many ways. I was overwhelmed by her sense of being: the jewelry, the hair accessories, the vibrant folk colours of Mexico, benches and decorations on the walls that she had painted herself and pottery from her travels around Mexico’s rural areas.

Her study and painting area was lined with books along one wall: German texts and Communist literature, influences of Mexican art and literature; white files which housed her correspondence and which she lovingly decorated; various publications which profiled her travels and those of her husband Diego.

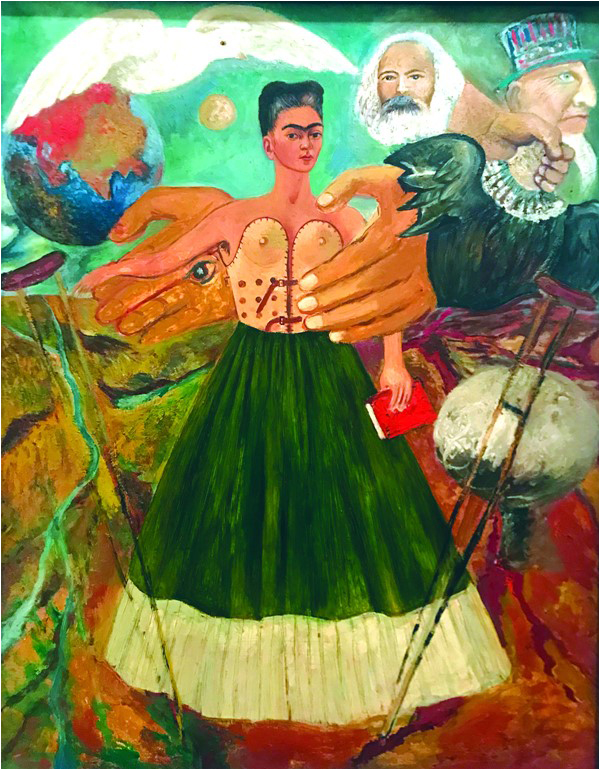

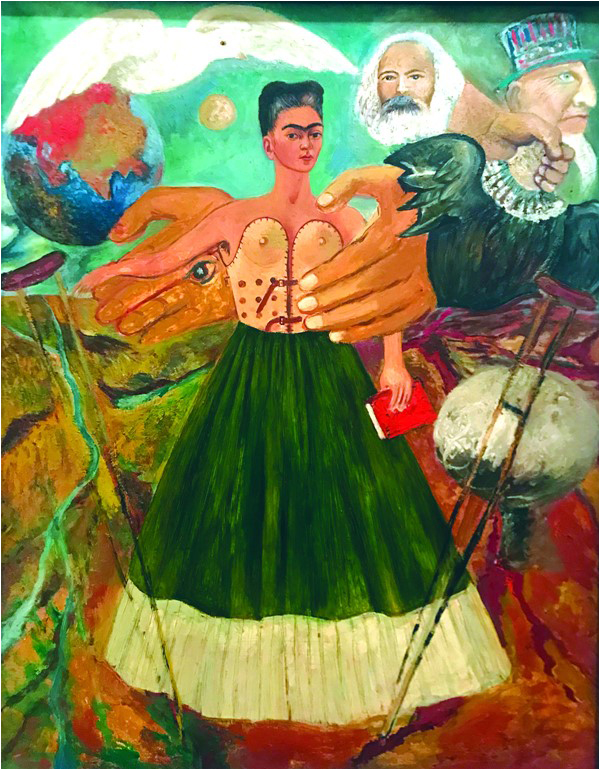

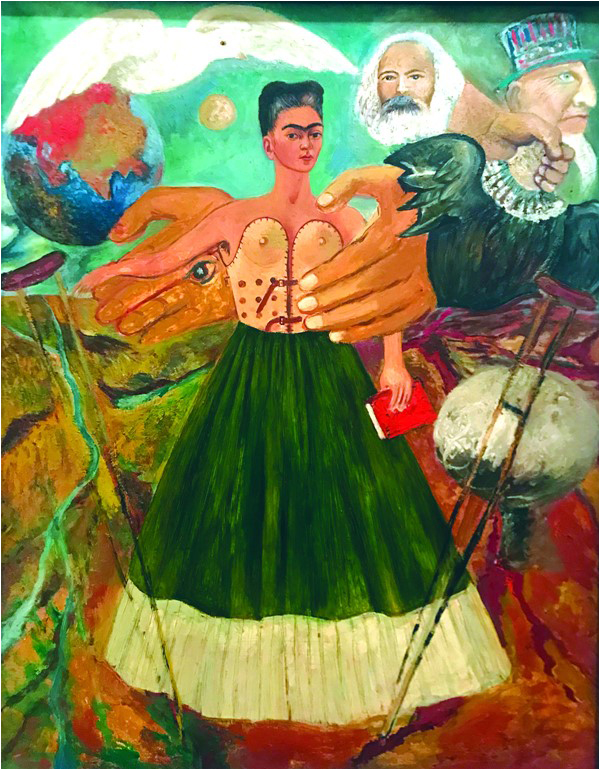

Her painting supplies were still spread out, as if ready to be used. When she did use them, she painted while lying down in bed or sitting in her wheelchair – flights of fantasy in colour. Of her 143 paintings, 55 were self-portraits which often incorporate symbolic portrayals of physical and psychological wounds.

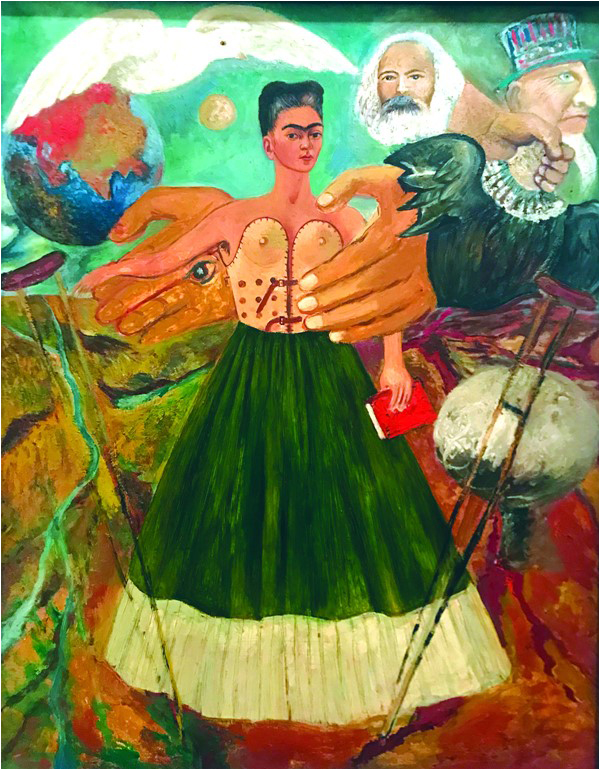

“I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality” she insisted. Her reality consisted of herself, her family and those who influenced her.

She was only 47 when she died in 1954, only a year after her first show in Mexico, garnering more critical acclaim abroad than in her own country. She was painfully aware of her own mortality. A few days before dying, she wrote in her diary: “I hope the exit is joyful – and I hope never to return.”

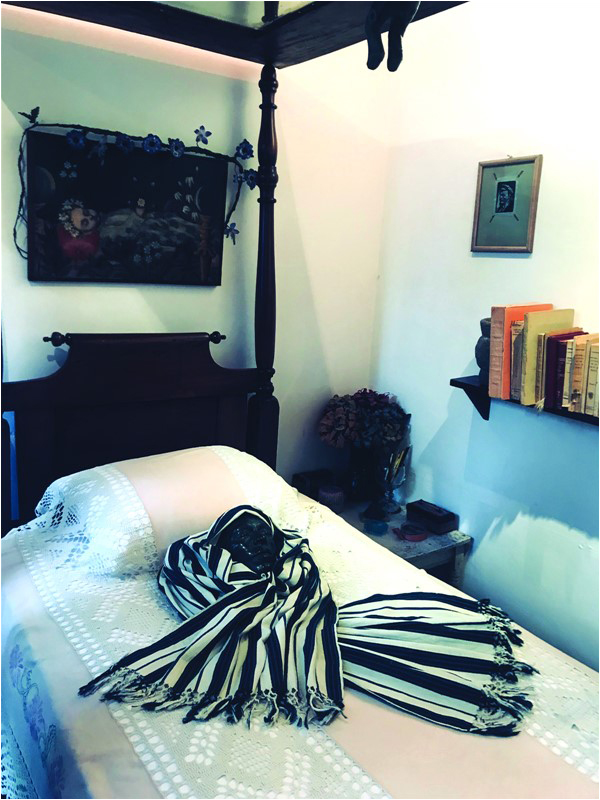

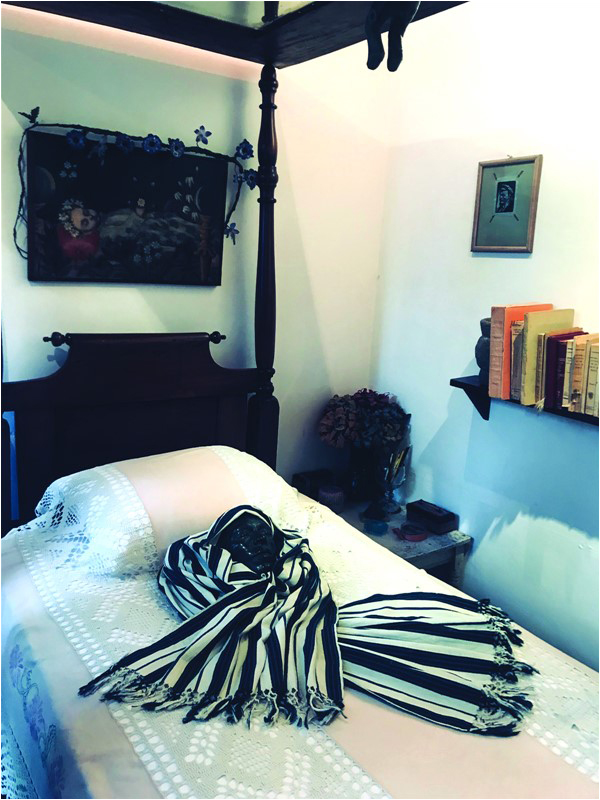

And yet in her home, it is as though she has never left. She left behind a house filled with her memories and experiences – photos with Leon Trotsky (with whom she had an affair after he was exiled by Stalin and arrived in Mexico) and mementoes of her various travels. Casa Azul is split on two levels, adapted to accommodate her condition. In later years, she moved from her study where she worked and closer to her four-poster bed where she rested.

Even now the room is configured to show what she could see – the photographs of various Communist figures at eye level, and various things she could see from her bed as she rested her frail body. Her cremated remains lie in her day bedroom where she rested, and one can sense her free spirit floating around what she had so lovingly created. It was almost too personal a room to step into – as if one were intruding into someone’s very private life.

One stipulation of her husband Diego’s final wishes was that some of her iconic clothes and corsets be exhibited, to coincide with her fiftieth death anniversary. Her clothes were released and form part of an exhibition in the outer rooms of the house. The exhibition has been carefully assembled by Vogue Mexico. Noticeable amongst them are her long skirts – symbols of her eclectic style but designed also to disguise her fragile legs, one of which was shorter than the other as a result of her polio, and the fantastic braids she wound around her head like a thick flowered crown of thorns. Her corsets were especially designed to protect her spinal cord after successive operations. Many years later, these formed the inspiration for Jean Paul Gaultier’s corset bustiers that Madonna wore.

Her artistic legacy has gone way beyond art to fashion – and now sadly even to fridge magnets peddled throughout Mexico!

Irvan Yolan defines the four givens of the human condition: death, meaning, isolation and freedom. In her life and death, Frida channeled all four aspects of this into a story larger than the sum of her turbulent, difficult but never boring life. Her house is more than her home. It is the narrative of her life.

Never did I understand the meaning of the word ‘dazzled’ better than after visiting the home of the Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, whose spectacular work justifies her reputation in Mexico. There, she has become a symbol, larger than life and at a par with her fiery artist husband Diego Rivera.

As a Pakistani, I empathize instinctively with Mexico. It carries the same sort of stigma in the international consciousness – a knee-jerk association with guns, drugs, lawlessness and furtive, oiled immigrants.

Mexico City is a beautiful surprise: leafy green squares and public spaces, a mixture of high-rise buildings with old haciendas nestling at their feet, the frenetic rush hour of commuters scurrying to work, stopping even in their urgency for a hurried snack at the informal food stalls which serve fresh corn tortillas with fried eggs and a hint of fresh jalapeno. One can see entrepreneurial energy sprouting out of every pavement. Who says a thriving start-up culture can be found only in California?

After meetings in the Coyoacan district, colleagues pointed out that we were in the same district as Frida Kahlo’s house – now a museum and the most visited site in Mexico City. It was one of those quick decisions that happen when one travels, but in retrospect, end up becoming the incredible experience that defines the trip.

Houses often assume the personalities of their occupants. Some are happy,others soulless. In many houses, one is no longer aware of the identity of those who once inhabited them. This is not the case In Casa Azul. Everything – her desk, her studio with jars of paints and her fiery paintings themselves – lay scattered about, just as if she were still alive.

Frida’s house is set in an area surrounded by other homes, but distinguishable from them by its bright azure blue and the spectrum of Mexico’s natural palette. Stucco pillars support the tiled roof which covered walkways between the house and its outer chambers, all built around a series of small courtyards. Rows of palm trees are planted alongside terracotta planters. When she was alive, peacocks used to run loose in the garden, providing their own splash of vivid colour.

It was in this house that Frida was born to a German-Jewish father and a native Mexican mother. Her father experimented with photography and as one wanders though the house, one can see the impact of his experimentation. As a child, Frida would accompany him to his dark room – partly to keep an eye on him in case he suffered an epileptic episode.

She grew up in the various courtyards, running around under the cactus trees. At the age of six, she suffered a polio attack. Another debilitating accident at age eighteen left her with a crushed spine. Years of operations meant she was in physical pain for the rest of her life. These setbacks did little to slow down her determination to enjoy life, nor did they dampen her artistic flair. She lived life beyond life itself, as only artists can – goaded but not subdued by suffering and pain.

Walking through her home, one gets a strong sense of the presence of her spirit – the creativity that erupts in so many ways. I was overwhelmed by her sense of being: the jewelry, the hair accessories, the vibrant folk colours of Mexico, benches and decorations on the walls that she had painted herself and pottery from her travels around Mexico’s rural areas.

Her study and painting area was lined with books along one wall: German texts and Communist literature, influences of Mexican art and literature; white files which housed her correspondence and which she lovingly decorated; various publications which profiled her travels and those of her husband Diego.

Her painting supplies were still spread out, as if ready to be used. When she did use them, she painted while lying down in bed or sitting in her wheelchair – flights of fantasy in colour. Of her 143 paintings, 55 were self-portraits which often incorporate symbolic portrayals of physical and psychological wounds.

“I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality” she insisted. Her reality consisted of herself, her family and those who influenced her.

She was only 47 when she died in 1954, only a year after her first show in Mexico, garnering more critical acclaim abroad than in her own country. She was painfully aware of her own mortality. A few days before dying, she wrote in her diary: “I hope the exit is joyful – and I hope never to return.”

And yet in her home, it is as though she has never left. She left behind a house filled with her memories and experiences – photos with Leon Trotsky (with whom she had an affair after he was exiled by Stalin and arrived in Mexico) and mementoes of her various travels. Casa Azul is split on two levels, adapted to accommodate her condition. In later years, she moved from her study where she worked and closer to her four-poster bed where she rested.

Even now the room is configured to show what she could see – the photographs of various Communist figures at eye level, and various things she could see from her bed as she rested her frail body. Her cremated remains lie in her day bedroom where she rested, and one can sense her free spirit floating around what she had so lovingly created. It was almost too personal a room to step into – as if one were intruding into someone’s very private life.

One stipulation of her husband Diego’s final wishes was that some of her iconic clothes and corsets be exhibited, to coincide with her fiftieth death anniversary. Her clothes were released and form part of an exhibition in the outer rooms of the house. The exhibition has been carefully assembled by Vogue Mexico. Noticeable amongst them are her long skirts – symbols of her eclectic style but designed also to disguise her fragile legs, one of which was shorter than the other as a result of her polio, and the fantastic braids she wound around her head like a thick flowered crown of thorns. Her corsets were especially designed to protect her spinal cord after successive operations. Many years later, these formed the inspiration for Jean Paul Gaultier’s corset bustiers that Madonna wore.

Her artistic legacy has gone way beyond art to fashion – and now sadly even to fridge magnets peddled throughout Mexico!

Irvan Yolan defines the four givens of the human condition: death, meaning, isolation and freedom. In her life and death, Frida channeled all four aspects of this into a story larger than the sum of her turbulent, difficult but never boring life. Her house is more than her home. It is the narrative of her life.