Disbelief. Anger. Rationalize. Repeat. Trump’s election, the Brexit vote, Modi’s arrival in India, ecological destruction, growing inequality, the refugee crisis, terrorism, and so on - there seems to be a certain script that many of us follow. After a few iterations, hopelessness probably creeps in as well. The night Trump won, Paul Krugman wrote that many people like him did not understand their country. Pankaj Mishra in his book Age of Anger notes how the current understanding of politics and society is simply not equipped to make sense of recent events and the forces driving them. In Dawn this week, Zarrar Khuhro described public sentiment as “disinterested and increasingly hostile” and how this is linked to the right wing. Clearly, the feeling of disillusionment and confusion is prevalent across society, with various groups exhibiting it in their own ways.

At the heart of this crisis is the absence of ideology in mainstream discourse. The definition of ideology has evolved over time; however, I loosely define it as a set of core beliefs that create a system of thinking which shapes how we see society and culture. So for example, neoliberalism is an ideology that prioritizes the individual over the collective, and hence, reduces all issues to individual rights, individual freedom and individual well-being.

Ideology is important for two reasons: first, it allows us to breakdown issues vertically and isolate core beliefs underlying each topic. For example, a typical factory owner pays workers abysmally because he is primarily concerned with his individual gains - a tenant of neoliberalism. Second, ideology allows horizontal linkages to be made between seemingly unrelated topics. So while the mental health crisis in schools, the decreasing fertility of our soil, and high income inequality may seem unrelated, they are, in fact, products of the same ideology.

Unfortunately, being ideological is considered dangerous today. Questioning or criticizing the system leads to labels such as “radical,” meant to stigmatize those that dare challenge dogmas that run our world. To be ideological, then, is to be a threat to stability and social cohesion, pushing society towards an abyss. While for centuries the presence of competing ideologies has fostered debate, and pushed knowledge to evolve and grow, we now have people, such as the notorious Canadian academic Jordan Peterson, that equate ideology with totalitarianism.

The driving force behind this situation is the move to a post-ideological era. From Obama during his campaigns for the US presidency, to Arvind Kejriwal of the Aam Aadmi Party in India, politicians are reluctant to associate themselves with an ideology, regardless of whether it is right-wing or left-wing. Climate scientists in the US face the risk of being stripped of the “objective” label if their research leads to advocacy against the prevalent system. In other strands of society as well, to identify with a belief system that challenges the status quo is stigmatized using the “ideological” label. We are taught to stay away from ideology and conform to a pre-determined definition of rational and objective.

This notion is closely tied to Francis Fukuyama’s ill-informed but grossly popular “end of history” thesis.

Towards the end of the 20th century, as western liberalism seemed to prevail over its communist arch-nemesis, it was touted that the world had finally, as predicted by enlightenment thinkers such as Kant, Hegel, and Marx, discovered an ideal model for society. There was no more need for ideological debate over systems as human subjectivity had been vanquished by rational, objective thinking. From then on, a technocratic, modern-day economist-esque approach was applied: every problem had a universal solution derived from science and evidence – all other considerations were superfluous.

This naïve - if not deceitful – approach has not yielded results that were promised. The debate between whether the idea itself was flawed or its execution was weak is another discussion. What is important, however, is that as a result of this notion being relentlessly propagated for decades, through think tanks and academia and international organizations, we now find ourselves in a space that is not organized by competing ideological systems, and hence, no alternative means of making sense of the world.

This does not mean that there is no more dominant ideology. Rather, the post-ideology narrative has cloaked the hegemony of neoliberalism behind a veil of objectivity. We are no longer aware that the political, social, and economic choices being made are part of a school of a thought, and that much of what we take as a matter of fact is actually subjective and contested. Are we individualistic beings? Is self-interest, greed, and an insatiable lust for consumption a natural state of being? What is the relationship between the state and its subjects? What role does religion play in society? Doctors treating depression, lawyers dealing with property rights, economists working on poverty, filmmakers conceiving their characters; all these examples, and more, are subject to, albeit unconsciously, an ideology.

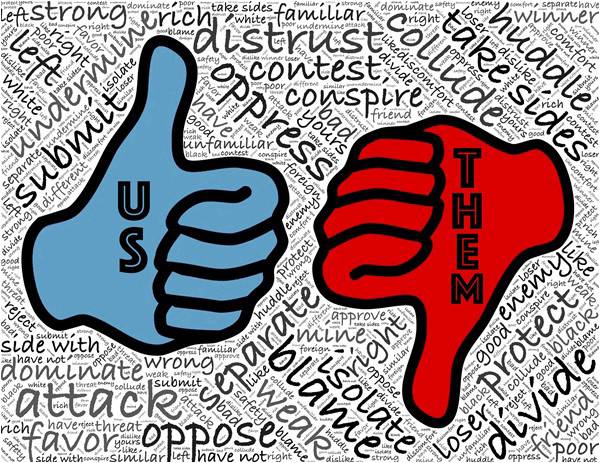

We are like fish in water, unaware that we are submerged in a particular medium, and that how the world appears to us is dependent on it. Our education system and media narratives indoctrinate us with this idea that there is no reality outside the status quo, actively restricting our imaginations from conceiving alternatives. The harm has been tremendous. Our means of constructive dialogue and debate have broken down, polarizing society to increasing heights. Operating in our own silos, we are unable to analyse the problems we see in the world around us, brewing disappointment and resentment within us, without any conducive outlet. Hence, we see people around the world resorting to a politics of hate and exclusion, reacting without purpose or direction.

It is imperative to de-stigmatize ideology in our schools, universities, research centers, and society in general. We need to recognize the deception in this post-ideological narrative, and that a plethora of issues across society are interlinked. Countering them individually is futile. New conceptions of society are essential to deal with issues ranging from climate change, discrimination, mental health, war, poverty, and so on. The goal is to not attach ourselves zealously to one ideology, as each has its flaws, but to restore debating ideas freely and understanding that these ideas directly shape the world around us.

At the heart of this crisis is the absence of ideology in mainstream discourse. The definition of ideology has evolved over time; however, I loosely define it as a set of core beliefs that create a system of thinking which shapes how we see society and culture. So for example, neoliberalism is an ideology that prioritizes the individual over the collective, and hence, reduces all issues to individual rights, individual freedom and individual well-being.

The post-ideology narrative has cloaked the hegemony of neoliberalism behind a veil of objectivity. We are no longer aware that the political, social, and economic choices being made are part of a school of a thought, and that much of what we take as a matter of fact is actually subjective and contested

Ideology is important for two reasons: first, it allows us to breakdown issues vertically and isolate core beliefs underlying each topic. For example, a typical factory owner pays workers abysmally because he is primarily concerned with his individual gains - a tenant of neoliberalism. Second, ideology allows horizontal linkages to be made between seemingly unrelated topics. So while the mental health crisis in schools, the decreasing fertility of our soil, and high income inequality may seem unrelated, they are, in fact, products of the same ideology.

Unfortunately, being ideological is considered dangerous today. Questioning or criticizing the system leads to labels such as “radical,” meant to stigmatize those that dare challenge dogmas that run our world. To be ideological, then, is to be a threat to stability and social cohesion, pushing society towards an abyss. While for centuries the presence of competing ideologies has fostered debate, and pushed knowledge to evolve and grow, we now have people, such as the notorious Canadian academic Jordan Peterson, that equate ideology with totalitarianism.

The driving force behind this situation is the move to a post-ideological era. From Obama during his campaigns for the US presidency, to Arvind Kejriwal of the Aam Aadmi Party in India, politicians are reluctant to associate themselves with an ideology, regardless of whether it is right-wing or left-wing. Climate scientists in the US face the risk of being stripped of the “objective” label if their research leads to advocacy against the prevalent system. In other strands of society as well, to identify with a belief system that challenges the status quo is stigmatized using the “ideological” label. We are taught to stay away from ideology and conform to a pre-determined definition of rational and objective.

This notion is closely tied to Francis Fukuyama’s ill-informed but grossly popular “end of history” thesis.

Towards the end of the 20th century, as western liberalism seemed to prevail over its communist arch-nemesis, it was touted that the world had finally, as predicted by enlightenment thinkers such as Kant, Hegel, and Marx, discovered an ideal model for society. There was no more need for ideological debate over systems as human subjectivity had been vanquished by rational, objective thinking. From then on, a technocratic, modern-day economist-esque approach was applied: every problem had a universal solution derived from science and evidence – all other considerations were superfluous.

This naïve - if not deceitful – approach has not yielded results that were promised. The debate between whether the idea itself was flawed or its execution was weak is another discussion. What is important, however, is that as a result of this notion being relentlessly propagated for decades, through think tanks and academia and international organizations, we now find ourselves in a space that is not organized by competing ideological systems, and hence, no alternative means of making sense of the world.

This does not mean that there is no more dominant ideology. Rather, the post-ideology narrative has cloaked the hegemony of neoliberalism behind a veil of objectivity. We are no longer aware that the political, social, and economic choices being made are part of a school of a thought, and that much of what we take as a matter of fact is actually subjective and contested. Are we individualistic beings? Is self-interest, greed, and an insatiable lust for consumption a natural state of being? What is the relationship between the state and its subjects? What role does religion play in society? Doctors treating depression, lawyers dealing with property rights, economists working on poverty, filmmakers conceiving their characters; all these examples, and more, are subject to, albeit unconsciously, an ideology.

We are like fish in water, unaware that we are submerged in a particular medium, and that how the world appears to us is dependent on it. Our education system and media narratives indoctrinate us with this idea that there is no reality outside the status quo, actively restricting our imaginations from conceiving alternatives. The harm has been tremendous. Our means of constructive dialogue and debate have broken down, polarizing society to increasing heights. Operating in our own silos, we are unable to analyse the problems we see in the world around us, brewing disappointment and resentment within us, without any conducive outlet. Hence, we see people around the world resorting to a politics of hate and exclusion, reacting without purpose or direction.

It is imperative to de-stigmatize ideology in our schools, universities, research centers, and society in general. We need to recognize the deception in this post-ideological narrative, and that a plethora of issues across society are interlinked. Countering them individually is futile. New conceptions of society are essential to deal with issues ranging from climate change, discrimination, mental health, war, poverty, and so on. The goal is to not attach ourselves zealously to one ideology, as each has its flaws, but to restore debating ideas freely and understanding that these ideas directly shape the world around us.

The author works at the Center for Economic Research Pakistan (CERP). His interests include socioeconomic and cultural developments. He tweets at @mtaa32