“The People of our locality were enraged, shouting slogans and just about to take the law into their own hands. They wanted to take ‘revenge’ by demolishing a Hindu temple. Everyone seemed to want to claim the title of being ‘the first to hurl a hammer at the Hindu temple’ for what they saw as a ‘holy cause’” remembers Raja Imtiaz Ahmed. Such was the response in Gujar Khan city, Pakistan, to the demolition of the Babri Mosque in India by Hindu zealots.

“We were running our small restaurant here. This disturbance was part of the countrywide protests in retaliation for the mosque that was attacked in India. Luckily, we settled down the furious mob and saved not only this Hindu temple but our business as well!” he recalls.

Raja Imtiaz Ahmed was but 18 years old at that time of madness. Today, he is 43 and runs a small business in the downtown area of Gujar Khan city.

His family, after Partition, moved from Mendhar tehsil of Poonch district to Gujar Khan.

“My father,Raja Muhammad Nazir ,was in the army. He told us that when they came to Gujar Khan, there was nothing left behind. The local Muslim residents had looted and set ablaze the property of rich Hindus who had fled to the newly created India.”

He continues:

“This area, where today the temple stands, was then littered with garbage and evidence of turmoil, and of the terrible things that the city had seen. My father cleaned that area and it was allotted to Kashmiri muhajireen (those displaced by the devastation of Partition in 1947). Since then, this nameless Hindu temple became known commonly as ‘Pahariyan Naa Mandir’ because we moved here from a hilly region and in the local Pothohari language, due to our geographical identity, we called ‘Pahariay’

His father had a lot of memories from that time but he has lost many of them by now. He is 95 years of age.

He says:

“We have great respect for this temple, the small room where moorties (representations of Hindu deities) were once placed. However, the room was stark and bereft of moorties since the time that we migrated here after Partition. We came here only barefoot. No one was allowed to enter inside that room wearing shoes. We actually lived in this temple for 15 years. Later we turned it into a restaurant, but this section left as it was.”

The town of Gujar Khan saw rapid expansion from a small town to a city when it was connected to the Railway network in the 1880s. It became a market for wheat, millet, peanuts and pulses, located on the Grand Trunk Road and in the middle of the wheat- and mustard-producing belt. Grain from Gujar Khan was sold to a large part of Kashmir and other northern areas. The commerce, dominated by ‘arhaatis’, was in the hands of Hindus and Sikhs, mainly living in the city area. From that presence, the city has many temples. There is a Gurudawara right in the heart of city today – the only one left.

As for the temple, Pahariyan Naa Mandir, it was built in the 1920s. What remains of it is still in a good condition, but the other rooms crumbled to the ground over the passage of time. The temple has 200 square metres of covered area. After the 1947 Partition, some five to seven families lived in the compound overall.

Imtiaz Ahmed wrote to the authorities many times for the preservation of this religious heritage site.

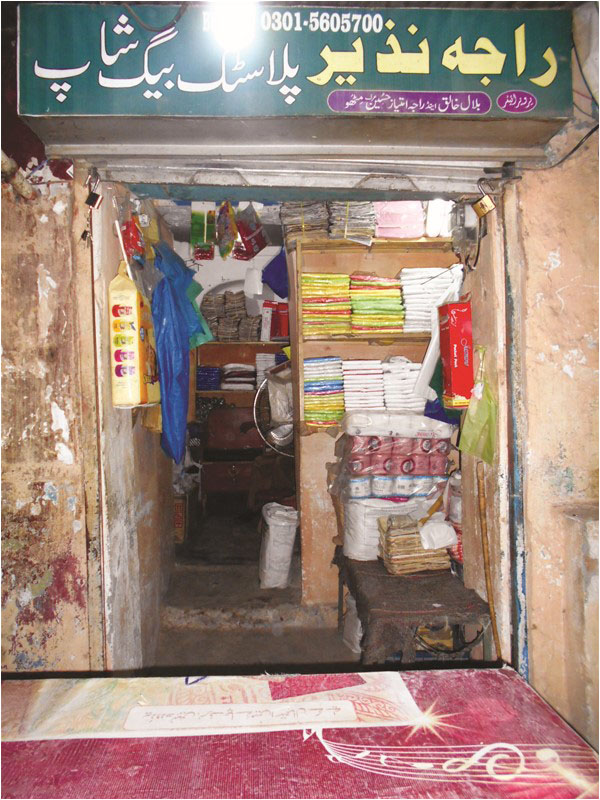

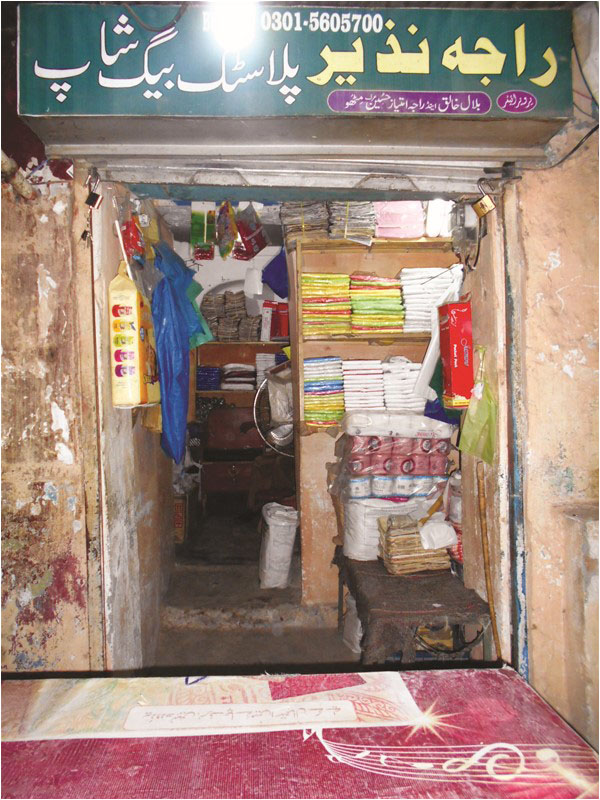

“We built our new house a few years back and now I run here my small business of plastic. Many Sikhs and Hindus quite frequently came to visit this site. Especially when they stayed in Rawalpindi and Islamabad. In 1998 or 1999, two Indian female journalists visited the temple. They were from Chandigarh and their families had moved from Gujar Khan to East Punjab during Partition. We had postal correspondence which lasted for many years. They shared with me stories of this temple as they had heard from their elders - and the nostalgia from that time, especially for their schoolmates!”

Imtiaz Ahmed had some of the architecture of the temple repaired from his own pocket. Later the Evacuee Trust Property Board (ETPB) took notice of it because it was technically illegal.

“You could see the Shikhara of the temple losing its grace and charm. How long could I take care of its upkeep by myself? This is our heritage site. If we respect their religious sites, they would respect ours!” believes Imtiaz Ahmed.

The 1992 Babri Mosque attack, and its demolition by Hindu fundamentalists, remains a dark chapter in the history of South Asia. This event triggered a chain of “retaliatory” attacks on Hindu sites in Pakistan. In fact, Hindu, Jain and Sikh places of worship were attacked on an even bigger scale than what took place during the murder, mayhem and chaos of 1947. The Pakistani Hindu community found themselves particularly suspect in the eyes of many local people in the aftermath of 1992. Unfortunately, the hostility of Pakistanis was not directed at the Indian government or those right-wing elements from India who were directly involved in demolishing the Babri mosque, but against their fellow Pakistanis – Hindus and their worship places living across Pakistan. In the wave of bigotry and violence, the places of worship of Sikhs and Jains became victim equally - the Jain temples in Lahore and Rawalpindi being but one example. Since many of these places of worship were in the heart of commercial hubs and urban centres, various elements fully availed themselves of the opportunity to turn a profit from bigotry – by taking over the premises.

Today, as signs of our pluralistic past are fast fading out in many parts of Pakistan, people like Imtiaz Ahmed are still on their lonely crusade of love – striving to spread a message of interfaith harmony in dark times.

“We were running our small restaurant here. This disturbance was part of the countrywide protests in retaliation for the mosque that was attacked in India. Luckily, we settled down the furious mob and saved not only this Hindu temple but our business as well!” he recalls.

Raja Imtiaz Ahmed was but 18 years old at that time of madness. Today, he is 43 and runs a small business in the downtown area of Gujar Khan city.

His family, after Partition, moved from Mendhar tehsil of Poonch district to Gujar Khan.

“My father,Raja Muhammad Nazir ,was in the army. He told us that when they came to Gujar Khan, there was nothing left behind. The local Muslim residents had looted and set ablaze the property of rich Hindus who had fled to the newly created India.”

"We came here only barefoot. No one was allowed to enter inside that room wearing shoes. We actually lived in this temple for 15 years"

He continues:

“This area, where today the temple stands, was then littered with garbage and evidence of turmoil, and of the terrible things that the city had seen. My father cleaned that area and it was allotted to Kashmiri muhajireen (those displaced by the devastation of Partition in 1947). Since then, this nameless Hindu temple became known commonly as ‘Pahariyan Naa Mandir’ because we moved here from a hilly region and in the local Pothohari language, due to our geographical identity, we called ‘Pahariay’

His father had a lot of memories from that time but he has lost many of them by now. He is 95 years of age.

He says:

“We have great respect for this temple, the small room where moorties (representations of Hindu deities) were once placed. However, the room was stark and bereft of moorties since the time that we migrated here after Partition. We came here only barefoot. No one was allowed to enter inside that room wearing shoes. We actually lived in this temple for 15 years. Later we turned it into a restaurant, but this section left as it was.”

The town of Gujar Khan saw rapid expansion from a small town to a city when it was connected to the Railway network in the 1880s. It became a market for wheat, millet, peanuts and pulses, located on the Grand Trunk Road and in the middle of the wheat- and mustard-producing belt. Grain from Gujar Khan was sold to a large part of Kashmir and other northern areas. The commerce, dominated by ‘arhaatis’, was in the hands of Hindus and Sikhs, mainly living in the city area. From that presence, the city has many temples. There is a Gurudawara right in the heart of city today – the only one left.

As for the temple, Pahariyan Naa Mandir, it was built in the 1920s. What remains of it is still in a good condition, but the other rooms crumbled to the ground over the passage of time. The temple has 200 square metres of covered area. After the 1947 Partition, some five to seven families lived in the compound overall.

Imtiaz Ahmed wrote to the authorities many times for the preservation of this religious heritage site.

“We built our new house a few years back and now I run here my small business of plastic. Many Sikhs and Hindus quite frequently came to visit this site. Especially when they stayed in Rawalpindi and Islamabad. In 1998 or 1999, two Indian female journalists visited the temple. They were from Chandigarh and their families had moved from Gujar Khan to East Punjab during Partition. We had postal correspondence which lasted for many years. They shared with me stories of this temple as they had heard from their elders - and the nostalgia from that time, especially for their schoolmates!”

The 1992 Babri Mosque attack, and its demolition by Hindu fundamentalists, remains a dark chapter in the history of South Asia. This event triggered a chain of "retaliatory" attacks on Hindu sites in Pakistan

Imtiaz Ahmed had some of the architecture of the temple repaired from his own pocket. Later the Evacuee Trust Property Board (ETPB) took notice of it because it was technically illegal.

“You could see the Shikhara of the temple losing its grace and charm. How long could I take care of its upkeep by myself? This is our heritage site. If we respect their religious sites, they would respect ours!” believes Imtiaz Ahmed.

The 1992 Babri Mosque attack, and its demolition by Hindu fundamentalists, remains a dark chapter in the history of South Asia. This event triggered a chain of “retaliatory” attacks on Hindu sites in Pakistan. In fact, Hindu, Jain and Sikh places of worship were attacked on an even bigger scale than what took place during the murder, mayhem and chaos of 1947. The Pakistani Hindu community found themselves particularly suspect in the eyes of many local people in the aftermath of 1992. Unfortunately, the hostility of Pakistanis was not directed at the Indian government or those right-wing elements from India who were directly involved in demolishing the Babri mosque, but against their fellow Pakistanis – Hindus and their worship places living across Pakistan. In the wave of bigotry and violence, the places of worship of Sikhs and Jains became victim equally - the Jain temples in Lahore and Rawalpindi being but one example. Since many of these places of worship were in the heart of commercial hubs and urban centres, various elements fully availed themselves of the opportunity to turn a profit from bigotry – by taking over the premises.

Today, as signs of our pluralistic past are fast fading out in many parts of Pakistan, people like Imtiaz Ahmed are still on their lonely crusade of love – striving to spread a message of interfaith harmony in dark times.