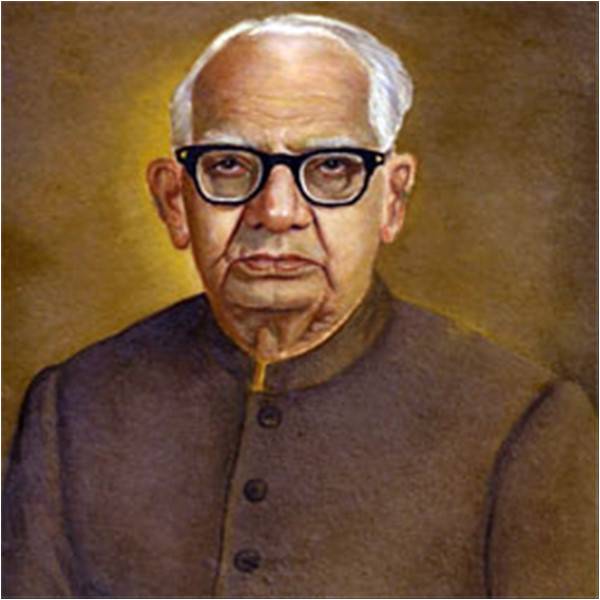

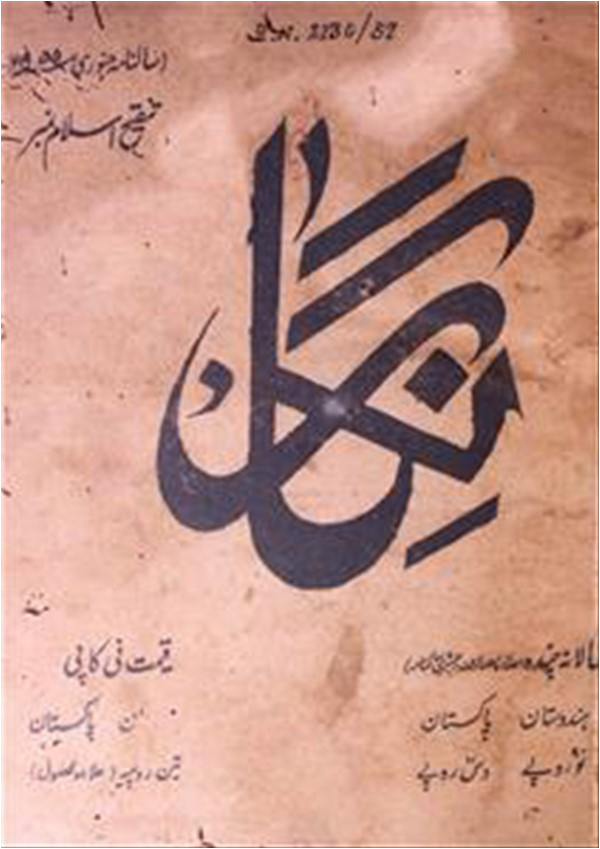

Allama Niaz Fatehpuri and his publication Nigar faced much backlash from conservative and religious forces for his positions.

While mentioning the fatwas against him, he writes:

“Preaching and publicity was done against my unbeliefs on a more organized manner from various places in India. So much so that a few associations which were under the influence of the local ‘mullah party’declared my alliance with Nigar unbearable and tried to desist people from buying Nigar. Some sage of Bihar province, a Maulvi Abdul Hakeem or Hakeem-ul-Din sahib, through a sermonising article in a newspaper of his province, ‘Ittehad’, informed the sons of the nation of the mischief-making of ‘Nigar’, declaring its perusal forbidden and unlawful. So much so that in this city of Lucknow, a few national and religious leaders also decided after holding a gathering to terminate even my temporary life. A few people sent me many letters of the intimidating and welcoming kind.Among local newspapers, the daily ‘Himmat’ and the weekly ‘Sach’ participated in this virtuous deed in a more organised and attentive manner. In short, everything happened during this time which could have been done with the help of journalism and propaganda. But I only responded with silence to these attacks; because out of all these people, there is not even one who established an opinion after a perusal of ‘Nigar’ in its entirety and I know that whatever is said is all a result of conjecture and guesswork and rumour of the public which is always meaningless or is a deliberateconcealmentof reality and a wrong interpretation of my words against myself, which might have been declared as permissible in their sober interpretation with respect to the principle of war or those who by way of preaching and publicity against me might be firmly determined to build a new palace in Heaven.”

With respect to freedom of thought, his perspective was similar to that of Voltaire, that freedom of expression is not just the monopoly of a few aged men but the birthright of every human – regardless of what faith, nation or school of thought they belong to – and whoever deprives people of this right is an enemy of humanity and freedom. The thoughts expressed through Nigar bear witness that Allama Niaz Fatehpuri remained firm on the same path all his life. He repeatedly invited his opponents to come and respond to his views with actual arguments.

Niaz Fatehpuri was a great admirer of the development that the world had achieved through scientific knowledge – and accordingly his thought, too, was scientific. For him, any idea, belief, totality and way of life which is far from human experiences, observations and reason is unacceptable. According to him:

“Science only forces us to believe things which we can prove to be accurate. Science wants to search events to arrive at the reality. It accords no status to one’s father or grandfather. It demands the use of reason […]”

In his view, making reason one’s sole guide is another name for freedom of thought. So he uses the following imagery:

“Look at the path guided by reason, how clean and even is that path, how open the air is, how full of spring is the earth. Every person is worried about reducing the burden of the other and every mind is worried for providing comfort and happiness to human beings. Neither there are any gallows nor jailhouses, neither pythons of Hell nor the whips of angels; but the vast atmosphere of nature, which is being benefitted from equally by every person. There is a sun of reason and wisdom which wants to benefit everyone equally. The chains of humanity have been cut. The stain of slavery is removed from Man’s forehead. Mental freedom has bloomed various types of orchards and every individual is seen to embrace the other.”

Niaz Fatehpuri was a very open-minded intellectual. His personal interest was neither attached to feudalism and capitalism nor to socialism, so he took a critical approach towards the societal problems of the present time, without hesitation. In his opinion:

“At the moment the most important thought before the world is not how Man should beware of sins but that what sort of change should be created in the civilisational and societal system so that Man does not die of hunger.”

He continues later:

“At the moment, in principle, approximately all countries have accepted that that the best form of government and empire is democracy and no other remedy except socialist principles existsfor the calamities with which the capitalist mentality has subjected the world; then is there any other religion except Islam which supports this contention?”

In another article he says:

“At the moment what has caused a commotion in the world is the war between capitalism and socialism, meaning that now the world cannot bear that divisions among humans should be based only on that one of them has a pile of wealth and the other is deprived of it. Wealth is a hypothetical power created by Man himself which can be used till the time everyone can benefit equally from it, but if this equality becomes extinct and the wealth is used to trample humanity, it should be removed. So you will see that at the moment every European country is influenced by this feeling and all those governments which were established on capitalist oppression and colonialism are being forced to follow socialist principles. Then if socialism spreads across the entire world and the meaning of wealth and poverty change completely, do you think at that moment humans will be against other humans and one party will confront the other party? Never. Because the whole conflict occurs because one is a capitalist, while the other is poor but if this conflict is removed and all humans arrive at the same level, there is no other reason for opposition.”

The reader must note that our purpose here is not to establish Allama Niaz Fatehpuri’s political credentials as a socialist or communist. The point, instead, is to indicate his inclinations of thought and his awareness of the spirit of the age.

He was, at the end of the day, a monotheist. On this basis, he was extremely opposed to beliefs and ideologies which led to, or might lead to, the scattering of the oneness of humanity. According to him, the standard of evaluating any societal system, any economic or political philosophy of civilisation or any religious belief was whether or not it is based on reason and justice. He asked whether it bring a person close to another or not – and whether it creates a feeling of mutual affection and empathy or not.

Niaz Fatehpuri has done us huge favours. He has played a prominent role in the intellectual training of many generations. Our intellectual horizons were broadened by his writings and we – who have been educated since childhood to say “yes” to anything – developed the courage to ask questions, which is the first stage in freedom of thought. But what a tragedy that today our textbooks are bereft of the writings of such a prose stylist and rationalist writer as NiazFatehpuri. The administrators of colleges and government institutions of mass communications avoid him like the Forbidden Tree. The centennial of Niaz Fatehpuri’s birth in 1984 went by, unnoticed and uncelebrated except a few progressive pockets in Karachi.

In more enlightened countries, very beautiful editions of the works of writers are published on the occasion of the centennial of their births and deaths. If we agree with Niaz Fatehpuri’s motto and love his writings, it is our obligation to try to have him included in the textbooks; to collect all his published and unpublished writings and publish them as a great project, so that new generations can also be introduced to his name and work. And if we cannot do this, then such celebrations and remembrances would be no more than the urs of yet another pir. n

Note: All the quotations are original translations from the Urdu done by the authorand can be found in Niaz Fatehpuri’s magnum opus ‘Man-o-Yazdaan’ (Man and God), 1966, Karachi

Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and award-winning translator and dramatic reader currently teaching in Lahore. He is also the president of the Progressive Writers Association in Lahore. His most recent work is an introduction to the reissued edition (HarperCollins India, 2016) of Abdullah Hussein’s classic novel ‘The Weary Generations’. He can be reached at razanaeem@hotmail.com

While mentioning the fatwas against him, he writes:

“Preaching and publicity was done against my unbeliefs on a more organized manner from various places in India. So much so that a few associations which were under the influence of the local ‘mullah party’declared my alliance with Nigar unbearable and tried to desist people from buying Nigar. Some sage of Bihar province, a Maulvi Abdul Hakeem or Hakeem-ul-Din sahib, through a sermonising article in a newspaper of his province, ‘Ittehad’, informed the sons of the nation of the mischief-making of ‘Nigar’, declaring its perusal forbidden and unlawful. So much so that in this city of Lucknow, a few national and religious leaders also decided after holding a gathering to terminate even my temporary life. A few people sent me many letters of the intimidating and welcoming kind.Among local newspapers, the daily ‘Himmat’ and the weekly ‘Sach’ participated in this virtuous deed in a more organised and attentive manner. In short, everything happened during this time which could have been done with the help of journalism and propaganda. But I only responded with silence to these attacks; because out of all these people, there is not even one who established an opinion after a perusal of ‘Nigar’ in its entirety and I know that whatever is said is all a result of conjecture and guesswork and rumour of the public which is always meaningless or is a deliberateconcealmentof reality and a wrong interpretation of my words against myself, which might have been declared as permissible in their sober interpretation with respect to the principle of war or those who by way of preaching and publicity against me might be firmly determined to build a new palace in Heaven.”

With respect to freedom of thought, his perspective was similar to that of Voltaire, that freedom of expression is not just the monopoly of a few aged men but the birthright of every human – regardless of what faith, nation or school of thought they belong to – and whoever deprives people of this right is an enemy of humanity and freedom. The thoughts expressed through Nigar bear witness that Allama Niaz Fatehpuri remained firm on the same path all his life. He repeatedly invited his opponents to come and respond to his views with actual arguments.

He was, at the end of the day, a monotheist. On this basis, he was extremely opposed to beliefs and ideologies which led to the scattering of the oneness of humanity

Niaz Fatehpuri was a great admirer of the development that the world had achieved through scientific knowledge – and accordingly his thought, too, was scientific. For him, any idea, belief, totality and way of life which is far from human experiences, observations and reason is unacceptable. According to him:

“Science only forces us to believe things which we can prove to be accurate. Science wants to search events to arrive at the reality. It accords no status to one’s father or grandfather. It demands the use of reason […]”

In his view, making reason one’s sole guide is another name for freedom of thought. So he uses the following imagery:

“Look at the path guided by reason, how clean and even is that path, how open the air is, how full of spring is the earth. Every person is worried about reducing the burden of the other and every mind is worried for providing comfort and happiness to human beings. Neither there are any gallows nor jailhouses, neither pythons of Hell nor the whips of angels; but the vast atmosphere of nature, which is being benefitted from equally by every person. There is a sun of reason and wisdom which wants to benefit everyone equally. The chains of humanity have been cut. The stain of slavery is removed from Man’s forehead. Mental freedom has bloomed various types of orchards and every individual is seen to embrace the other.”

Niaz Fatehpuri was a very open-minded intellectual. His personal interest was neither attached to feudalism and capitalism nor to socialism, so he took a critical approach towards the societal problems of the present time, without hesitation. In his opinion:

“At the moment the most important thought before the world is not how Man should beware of sins but that what sort of change should be created in the civilisational and societal system so that Man does not die of hunger.”

He continues later:

“At the moment, in principle, approximately all countries have accepted that that the best form of government and empire is democracy and no other remedy except socialist principles existsfor the calamities with which the capitalist mentality has subjected the world; then is there any other religion except Islam which supports this contention?”

In another article he says:

“At the moment what has caused a commotion in the world is the war between capitalism and socialism, meaning that now the world cannot bear that divisions among humans should be based only on that one of them has a pile of wealth and the other is deprived of it. Wealth is a hypothetical power created by Man himself which can be used till the time everyone can benefit equally from it, but if this equality becomes extinct and the wealth is used to trample humanity, it should be removed. So you will see that at the moment every European country is influenced by this feeling and all those governments which were established on capitalist oppression and colonialism are being forced to follow socialist principles. Then if socialism spreads across the entire world and the meaning of wealth and poverty change completely, do you think at that moment humans will be against other humans and one party will confront the other party? Never. Because the whole conflict occurs because one is a capitalist, while the other is poor but if this conflict is removed and all humans arrive at the same level, there is no other reason for opposition.”

The reader must note that our purpose here is not to establish Allama Niaz Fatehpuri’s political credentials as a socialist or communist. The point, instead, is to indicate his inclinations of thought and his awareness of the spirit of the age.

He was, at the end of the day, a monotheist. On this basis, he was extremely opposed to beliefs and ideologies which led to, or might lead to, the scattering of the oneness of humanity. According to him, the standard of evaluating any societal system, any economic or political philosophy of civilisation or any religious belief was whether or not it is based on reason and justice. He asked whether it bring a person close to another or not – and whether it creates a feeling of mutual affection and empathy or not.

Niaz Fatehpuri has done us huge favours. He has played a prominent role in the intellectual training of many generations. Our intellectual horizons were broadened by his writings and we – who have been educated since childhood to say “yes” to anything – developed the courage to ask questions, which is the first stage in freedom of thought. But what a tragedy that today our textbooks are bereft of the writings of such a prose stylist and rationalist writer as NiazFatehpuri. The administrators of colleges and government institutions of mass communications avoid him like the Forbidden Tree. The centennial of Niaz Fatehpuri’s birth in 1984 went by, unnoticed and uncelebrated except a few progressive pockets in Karachi.

In more enlightened countries, very beautiful editions of the works of writers are published on the occasion of the centennial of their births and deaths. If we agree with Niaz Fatehpuri’s motto and love his writings, it is our obligation to try to have him included in the textbooks; to collect all his published and unpublished writings and publish them as a great project, so that new generations can also be introduced to his name and work. And if we cannot do this, then such celebrations and remembrances would be no more than the urs of yet another pir. n

Note: All the quotations are original translations from the Urdu done by the authorand can be found in Niaz Fatehpuri’s magnum opus ‘Man-o-Yazdaan’ (Man and God), 1966, Karachi

Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and award-winning translator and dramatic reader currently teaching in Lahore. He is also the president of the Progressive Writers Association in Lahore. His most recent work is an introduction to the reissued edition (HarperCollins India, 2016) of Abdullah Hussein’s classic novel ‘The Weary Generations’. He can be reached at razanaeem@hotmail.com