Biennales in the context of Visual Art are large scale exhibitions held once every two years. The origin of the format takes us back to 1895, which marked the opening of the prestigious Venice Biennale, following additions of pavilions each year. It was in the 1990s that Biennales sprouted in various other cities across the globe, helping shift the focus of art from major art centers to other locations. Today there are over 200 biennales held across the globe, such as those in Sao Paulo, Vancouver, Istanbul, Gwangju, Sydney, Havana, Lyon and Sharjah.

With the launch of the first ever Karachi Biennale a few months back and recently the Lahore Biennale, Pakistan has also emerged on the map of the art world in a big way, providing a fresh perspective in terms of interpretation of art – taking it out of the context of galleries into public spaces. This has helped in building a relationship between art and the masses. It has also led to Pakistan becoming host to an international audience of artists, curators and writers – thereby promoting dialogue and interaction with new voices.

The Lahore Biennale was inaugurated on the 18th of March 2018 with its primary focus on the rich and loaded history of a city whose origins reach into antiquity – controlled by numerous empires throughout the course of its past, including the Hindu Shahis, Ghaznavids, Ghurids and the Delhi Sultanate by the medieval era, reaching the height of its grandeur during the Mughal period.

My tour of the Biennale along with a fellow artist friend started from Bagh-e-Jinnah where we came across numerous site specific works encompassing the soul and spirit of that public space, commonly referred to as the Garden of Lovers. Ali Kazim’s configuration of fragile clay hearts stacked in an orderly manner resembled the ruins of an archaeological site, these countless terracotta hearts paying homage to numerous recurring stories and intimate moments spanning decades – suggestive of love, affection and belonging. Simultaneously the excitement around Mehreen Murtaza’s sound installation in relation to a tree was overwhelming and attracted large numbers as viewers gathered to hear and touch the tree. Amongst other works that stood out was the work of Noor Ali Chagani that challenged ideas relating to masculine identities, notions that restrict portrayal of the softer side of the male gender. His brick installation thus had a soft, organic feel to it negating the rigidity of bricks and structures otherwise – creating a sense of disorder and discontent.

Our next site was the Alhamra Arts Council that greeted us with Komail Aijazuddin’s gold cube at the entrance, comprising of 12 freestanding cement panels, each separated by red metal divisions. The 12 gold panels were reminiscent of the 12 historic gates of the City of Gardens, Lahore. Also on display at Alhamra were the works of renowned Pakistani American artist Shahzia Sikandar that were enormous in every manner, from the numerous conceptual layers present in the work to the massive scale. The animations accompanied by music were a treat to watch. Her work Parallax comprised of a three-way projection along with award-winning Chinese composer Du Yun’s music composition.

The Lahore Museum hosted some noticeable, intriguing and engaging works such as Bani Abidi’s sound installation around the historic Queen Victoria Statue, that stemmed from her practice based on letters and folk songs.

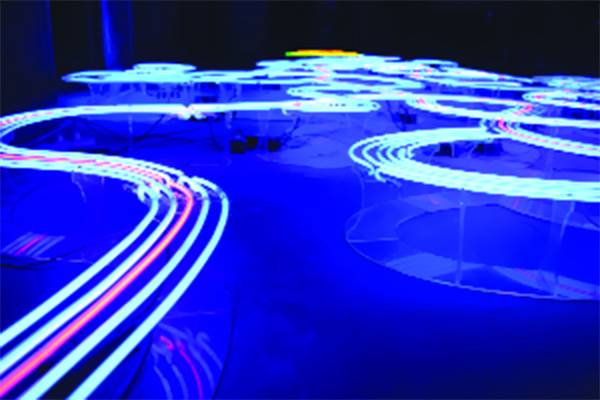

The final site that we made our way to was the Summer Palace in the Lahore Fort, that had on display the works of quite a few eminent Pakistani and international artists of our time. My favorite picks from this site included works of Iftikhar and Elizabeth Dadi, who did justice to the site in the most fascinating manner. Their neon light installation titled ‘Roz o Shab’ included a network of blue neon spread on an area, threaded through with red neon light, rewarding the eye locating the maze on a continuous route, bridging the outside and the inside – and also recalling the labyrinthine structures typical of Mughal architecture.

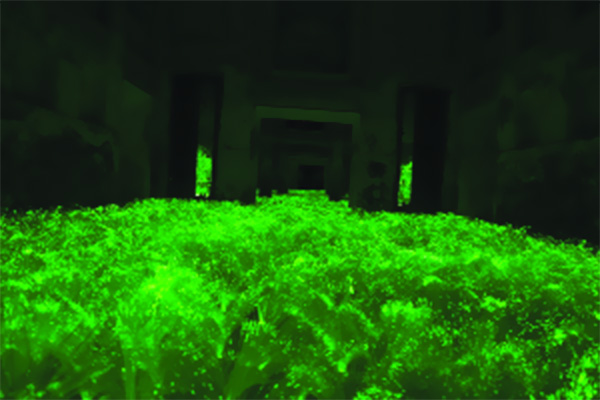

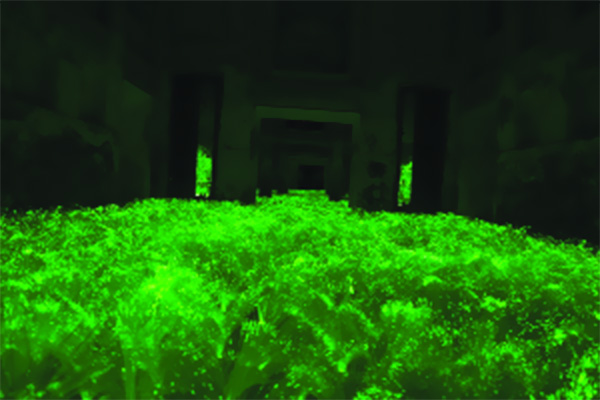

Imran Qureshi’s work was on display, highlighting the evident reality of today’s artificial landscape. In his installation he made use of numerous optic fibres emitting green light, hence creating a field extending into infinity with the use of mirrors, to resemble an endless unnatural steppe blinding the eyes.

Firoz Mahmud’s work shifted our focus to another kind of blindness. His prints displayed in light boxes depicted Bangladeshi textile workers wearing optical devices made from textile machinery parts. The workers temporarily attempt to assume the role of the viewer as opposed to that of the one being suppressed.

Huma Mulji’s work, like always, emerged from the unnoticeable, confronting the viewer with situations of exchange that often go unnoticed in an increasingly urbanised society. In this work she makes public an interaction of hers with a local bread seller.

Other aspects of the Biennale included the Academic Forum, ArtSpeak and Youth Forum, involving panel discussions, guided tours, workshops and artist talks. Taking into account the struggles faced by LBF this past year, pulling off the Biennale is big enough of a reason to value the efforts of everyone that made it happen, with Qudsia Rahim being the force behind it.

There is no denying the flaws, but I would insist that there are a lot of positives to take from this mega event – and I believe those are the aspects that need to be spoken of most. One hopes the next edition would be bigger and better.

Talal Faisal is an artist based in Lahore

With the launch of the first ever Karachi Biennale a few months back and recently the Lahore Biennale, Pakistan has also emerged on the map of the art world in a big way, providing a fresh perspective in terms of interpretation of art – taking it out of the context of galleries into public spaces. This has helped in building a relationship between art and the masses. It has also led to Pakistan becoming host to an international audience of artists, curators and writers – thereby promoting dialogue and interaction with new voices.

The Lahore Biennale was inaugurated on the 18th of March 2018 with its primary focus on the rich and loaded history of a city whose origins reach into antiquity – controlled by numerous empires throughout the course of its past, including the Hindu Shahis, Ghaznavids, Ghurids and the Delhi Sultanate by the medieval era, reaching the height of its grandeur during the Mughal period.

My tour of the Biennale along with a fellow artist friend started from Bagh-e-Jinnah where we came across numerous site specific works encompassing the soul and spirit of that public space, commonly referred to as the Garden of Lovers. Ali Kazim’s configuration of fragile clay hearts stacked in an orderly manner resembled the ruins of an archaeological site, these countless terracotta hearts paying homage to numerous recurring stories and intimate moments spanning decades – suggestive of love, affection and belonging. Simultaneously the excitement around Mehreen Murtaza’s sound installation in relation to a tree was overwhelming and attracted large numbers as viewers gathered to hear and touch the tree. Amongst other works that stood out was the work of Noor Ali Chagani that challenged ideas relating to masculine identities, notions that restrict portrayal of the softer side of the male gender. His brick installation thus had a soft, organic feel to it negating the rigidity of bricks and structures otherwise – creating a sense of disorder and discontent.

Our next site was the Alhamra Arts Council that greeted us with Komail Aijazuddin’s gold cube at the entrance, comprising of 12 freestanding cement panels, each separated by red metal divisions. The 12 gold panels were reminiscent of the 12 historic gates of the City of Gardens, Lahore. Also on display at Alhamra were the works of renowned Pakistani American artist Shahzia Sikandar that were enormous in every manner, from the numerous conceptual layers present in the work to the massive scale. The animations accompanied by music were a treat to watch. Her work Parallax comprised of a three-way projection along with award-winning Chinese composer Du Yun’s music composition.

The Lahore Museum hosted some noticeable, intriguing and engaging works such as Bani Abidi’s sound installation around the historic Queen Victoria Statue, that stemmed from her practice based on letters and folk songs.

The final site that we made our way to was the Summer Palace in the Lahore Fort, that had on display the works of quite a few eminent Pakistani and international artists of our time. My favorite picks from this site included works of Iftikhar and Elizabeth Dadi, who did justice to the site in the most fascinating manner. Their neon light installation titled ‘Roz o Shab’ included a network of blue neon spread on an area, threaded through with red neon light, rewarding the eye locating the maze on a continuous route, bridging the outside and the inside – and also recalling the labyrinthine structures typical of Mughal architecture.

Imran Qureshi’s work was on display, highlighting the evident reality of today’s artificial landscape. In his installation he made use of numerous optic fibres emitting green light, hence creating a field extending into infinity with the use of mirrors, to resemble an endless unnatural steppe blinding the eyes.

Firoz Mahmud’s work shifted our focus to another kind of blindness. His prints displayed in light boxes depicted Bangladeshi textile workers wearing optical devices made from textile machinery parts. The workers temporarily attempt to assume the role of the viewer as opposed to that of the one being suppressed.

Huma Mulji’s work, like always, emerged from the unnoticeable, confronting the viewer with situations of exchange that often go unnoticed in an increasingly urbanised society. In this work she makes public an interaction of hers with a local bread seller.

Other aspects of the Biennale included the Academic Forum, ArtSpeak and Youth Forum, involving panel discussions, guided tours, workshops and artist talks. Taking into account the struggles faced by LBF this past year, pulling off the Biennale is big enough of a reason to value the efforts of everyone that made it happen, with Qudsia Rahim being the force behind it.

There is no denying the flaws, but I would insist that there are a lot of positives to take from this mega event – and I believe those are the aspects that need to be spoken of most. One hopes the next edition would be bigger and better.

Talal Faisal is an artist based in Lahore