“Zindag? ky? hai an?sir meñ zuh?r-e-tart?b/Maut ky? hai inh?ñ ajz? k? paresh?ñ hon?”

“What is Life but a harmony of the elements/What is Death but a disorder amongst the same”

It was a typical morning in my very large, very busy public hospital. I was sitting in my morning clinic, trying to keep up with the crush of patients. The room in which I was sitting was, as usual, packed with people. Every few minutes I would yell at the doorman to stop sending more people in until the ones already inside were seen and left. The din inside and outside the room made it hard to listen to anyone. On top of everything else, I was in the middle of a nasty bout of flu.

There were two rickety tables in the room surrounded by plastic chairs. Along one wall was a steel bench on which patients would wait, but invariably, while I was in the middle of trying to talk to a patient, a few others would sidle up and either try to get my attention or sit down in one of the chairs around the table and lean in, trying to eavesdrop on what was being discussed. I would pause, glare at them and if they didn’t take the hint, order them back to the bench.

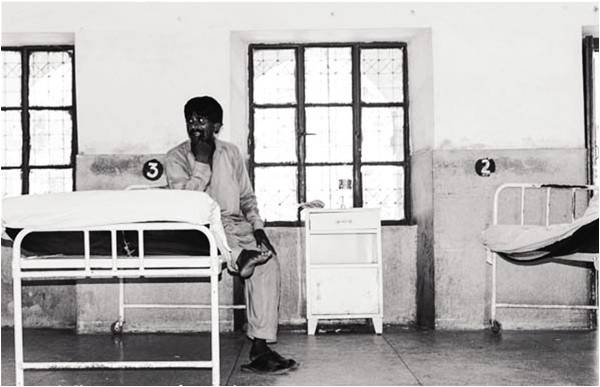

Many years ago, when I had first returned to Pakistan after having practiced Psychiatry in the United States for almost 12 years, I was appalled at the physical conditions of the hospital where I had started working (even though before going to America, I had studied there for almost six years). The area where patients arrived to register resembled more of an overcrowded bus stop than a hospital. The corridors on most days were impassable and the rooms where patients were checked were crumbling, unhygienic and totally unsuitable for examinations.

Privacy was unheard of and even people with the most private medical complaints had to talk to the doctors in full view of dozens of other people. When I had complained to my (then) boss of these conditions, he had laughed and told me to let go of my ‘American inhibitions’. I have never grown used to it though, mainly because the work that I do requires people to tell me things that they would not even discuss with their closest loved ones, let alone in front of strangers.

Most of the patients waiting to be seen in my clinic are poor and many travel long distances to come see us. Most of the women wear burqas or hijabs but in this place, modesty is an inconvenience. I usually ask them to sit in the chair next to me, lean in close to their face, my legs almost touching theirs and try and hear what they are saying. Sometimes I point at their lips and ask them to lower the cloth covering it so I can understand them. They don’t object.

I had been at it for more than an hour and a half, probably having seen ten or more patients. My throat was parched, my head was hurting and my mood was becoming exceedingly foul when she slid into the chair opposite me. A middle-aged woman with a dark complexion, she looked vaguely familiar. “Doctor sahib, thank God you are here. This is the third time I have come looking for you”. It turns out that one of her daughters had been admitted to our hospital a few years ago and I had treated her. She had recovered and was now doing quite well. She had come to find me because a younger daughter was now unwell. The daughter was not with her but from her description, she was exceedingly sick. “Doctor sahib, I cannot bring her here, she is too sick. We have got her chained at home, we cannot go near her, she is very violent. She tears off all her clothes and tries to attack whoever gets near her. She throws things at us, even her feces. Please doctor sahib, you must help me”.

From her description, it appeared that the patient was psychotic and quite ill. It must have taken a few months for her to get to this state. There was no way for me to know for sure what the girl was suffering from, but examining her was not a luxury I had available. I tried to persuade the woman to bring the girl in and have her admitted in our hospital where we could care for her properly but she was adamant, “Doctor sahib, it’s not possible. You know I am a widow woman with four daughters, I have no man at home to help me, I cannot bring her here by myself, please, help me”.

This kind of ‘catch-22’ situation, where there are no easy solutions, is quite common in my work. I debated whether I could ask the woman in front of me to medicate her daughter against her will by mixing medicines in her food (a practice I wrote about in this article http://tns.thenews.com.pk/mad/). I decided against it because it appeared that the patient was too sick to even be fed by her family. Absent an admission to the hospital, my hands were tied. If I were practicing in the US, it would be easy to get her to the hospital. I would tell the mother to submit an application to a judge, asking that the patient be ‘committed’ to a psychiatric hospital for involuntary treatment. If needed, I would write a letter to the judge supporting the application. Once the judge ordered the person to be admitted, the police would go to the woman’s home and bring the patient to the hospital. Alternatively, the patient’s mother could first go to the police and have them pick up the patient and bring her to the police station where a staff member from our hospital could go and examine her. If we felt she needed to be admitted (which in this case seemed fairly obvious), we would order a temporary ‘hold’ to have her admitted and we would then apply to the judge the next working day. In any case, there was a prescribed legal framework for dealing with such situations and necessary state resources were available to enforce it.

In Pakistan, although on paper we do have a fledgling ‘Mental Health Act’ (first formulated in 2001), there is, in actual practice, no practical framework on how to implement it and no resources available to do so. I advised the woman the only thing I could think of: give the girl an injection of an antipsychotic medication in the hopes of calming her down temporarily so she could be brought to the hospital and treated. I wrote down the injection on a prescription and explained to the mother what needed to be done. “Doctor sahib, we can get the injection from the hospital, right?” I told her no, she would have to buy it from a pharmacy. “Please doctor sahib, you know how poor I am, how can I buy the medicine? Please help me”.

Here was the next problem. Our large public hospital provided (some) medicines to people admitted but in most cases, ‘out-patients’ i.e. patients being seen in the clinics were not entitled to receive medicines from the hospital. There was a pharmacy which was supposed to supply some medicines but they almost never had anything available despite my having made numerous entreaties to the administration. Patients not being given medicines when discharged might not be a big problem in the case of acute conditions which resolve quickly (infections, fractures etc) but in the work that I do, medicines often need to be continued for months, sometimes years if the patient is to remain well. This was a constant challenge: destitute patients who got better while they were in the hospital relapsed promptly for lack of medicines once they got home, leading to a revolving door of repeated admissions and a steady worsening of their illness as they had more and more relapses. A few years ago, tired of this constant merry-go-round, I had approached friends in the US to donate money to set up a ‘drug bank’ in our hospital and now, every few months, I would go back to the same friends, ask for money, and then replenish the medicines. But this was a drop in the bucket compared to the need. And it was going to be no help to the woman sitting in front of me since the injection was not available in the drug bank.

I tried to think, my head throbbing, and couldn’t really come up with a good solution. Finally, I beckoned one of my junior doctors over, took out my wallet and handed her 500 rupees and told her to go get the injection from the pharmacy outside the hospital. When the injection arrived, I handed it to the woman along with a syringe and told her to find someone in her neighborhood to give her daughter the injection. I told her it would calm her daughter down for at least two to three days but that she would need continuing treatment after that and to bring her in as soon as she could.

It’s now been a couple of weeks and I haven’t heard back from her. Since our hospital, like most public hospitals, keeps no medical records, I have no way of contacting the woman. I keep hoping she will show back up in my clinic, her daughter in tow. Until then, I keep doing my clinic where we all spend most of our day trying to keep our head above water, trying to treat the poorest of the poor with our hands effectively tied behind our backs. If it were not for the generosity of the people of Pakistan as well as Pakistanis abroad, our public health system would have collapsed long ago. As it is, it continues to hang by a thread waiting for the day when our government will finally wake up to its responsibility.

The writer is a psychiatrist practicing in Lahore. He taught and practiced Psychiatry in the US for 16 years @Ali_Madeeh

“What is Life but a harmony of the elements/What is Death but a disorder amongst the same”

– Brij Narayan Chakbast (1882-1926)

It was a typical morning in my very large, very busy public hospital. I was sitting in my morning clinic, trying to keep up with the crush of patients. The room in which I was sitting was, as usual, packed with people. Every few minutes I would yell at the doorman to stop sending more people in until the ones already inside were seen and left. The din inside and outside the room made it hard to listen to anyone. On top of everything else, I was in the middle of a nasty bout of flu.

There were two rickety tables in the room surrounded by plastic chairs. Along one wall was a steel bench on which patients would wait, but invariably, while I was in the middle of trying to talk to a patient, a few others would sidle up and either try to get my attention or sit down in one of the chairs around the table and lean in, trying to eavesdrop on what was being discussed. I would pause, glare at them and if they didn’t take the hint, order them back to the bench.

Many years ago, when I had first returned to Pakistan after having practiced Psychiatry in the United States for almost 12 years, I was appalled at the physical conditions of the hospital where I had started working (even though before going to America, I had studied there for almost six years). The area where patients arrived to register resembled more of an overcrowded bus stop than a hospital. The corridors on most days were impassable and the rooms where patients were checked were crumbling, unhygienic and totally unsuitable for examinations.

"Doctor sahib, I cannot bring her here, she is too sick. We have got her chained at home, we cannot go near her, she is very violent. She tears off all her clothes and tries to attack whoever gets near her...

Privacy was unheard of and even people with the most private medical complaints had to talk to the doctors in full view of dozens of other people. When I had complained to my (then) boss of these conditions, he had laughed and told me to let go of my ‘American inhibitions’. I have never grown used to it though, mainly because the work that I do requires people to tell me things that they would not even discuss with their closest loved ones, let alone in front of strangers.

Most of the patients waiting to be seen in my clinic are poor and many travel long distances to come see us. Most of the women wear burqas or hijabs but in this place, modesty is an inconvenience. I usually ask them to sit in the chair next to me, lean in close to their face, my legs almost touching theirs and try and hear what they are saying. Sometimes I point at their lips and ask them to lower the cloth covering it so I can understand them. They don’t object.

I had been at it for more than an hour and a half, probably having seen ten or more patients. My throat was parched, my head was hurting and my mood was becoming exceedingly foul when she slid into the chair opposite me. A middle-aged woman with a dark complexion, she looked vaguely familiar. “Doctor sahib, thank God you are here. This is the third time I have come looking for you”. It turns out that one of her daughters had been admitted to our hospital a few years ago and I had treated her. She had recovered and was now doing quite well. She had come to find me because a younger daughter was now unwell. The daughter was not with her but from her description, she was exceedingly sick. “Doctor sahib, I cannot bring her here, she is too sick. We have got her chained at home, we cannot go near her, she is very violent. She tears off all her clothes and tries to attack whoever gets near her. She throws things at us, even her feces. Please doctor sahib, you must help me”.

From her description, it appeared that the patient was psychotic and quite ill. It must have taken a few months for her to get to this state. There was no way for me to know for sure what the girl was suffering from, but examining her was not a luxury I had available. I tried to persuade the woman to bring the girl in and have her admitted in our hospital where we could care for her properly but she was adamant, “Doctor sahib, it’s not possible. You know I am a widow woman with four daughters, I have no man at home to help me, I cannot bring her here by myself, please, help me”.

This kind of ‘catch-22’ situation, where there are no easy solutions, is quite common in my work. I debated whether I could ask the woman in front of me to medicate her daughter against her will by mixing medicines in her food (a practice I wrote about in this article http://tns.thenews.com.pk/mad/). I decided against it because it appeared that the patient was too sick to even be fed by her family. Absent an admission to the hospital, my hands were tied. If I were practicing in the US, it would be easy to get her to the hospital. I would tell the mother to submit an application to a judge, asking that the patient be ‘committed’ to a psychiatric hospital for involuntary treatment. If needed, I would write a letter to the judge supporting the application. Once the judge ordered the person to be admitted, the police would go to the woman’s home and bring the patient to the hospital. Alternatively, the patient’s mother could first go to the police and have them pick up the patient and bring her to the police station where a staff member from our hospital could go and examine her. If we felt she needed to be admitted (which in this case seemed fairly obvious), we would order a temporary ‘hold’ to have her admitted and we would then apply to the judge the next working day. In any case, there was a prescribed legal framework for dealing with such situations and necessary state resources were available to enforce it.

In Pakistan, although on paper we do have a fledgling ‘Mental Health Act’ (first formulated in 2001), there is, in actual practice, no practical framework on how to implement it and no resources available to do so. I advised the woman the only thing I could think of: give the girl an injection of an antipsychotic medication in the hopes of calming her down temporarily so she could be brought to the hospital and treated. I wrote down the injection on a prescription and explained to the mother what needed to be done. “Doctor sahib, we can get the injection from the hospital, right?” I told her no, she would have to buy it from a pharmacy. “Please doctor sahib, you know how poor I am, how can I buy the medicine? Please help me”.

Here was the next problem. Our large public hospital provided (some) medicines to people admitted but in most cases, ‘out-patients’ i.e. patients being seen in the clinics were not entitled to receive medicines from the hospital. There was a pharmacy which was supposed to supply some medicines but they almost never had anything available despite my having made numerous entreaties to the administration. Patients not being given medicines when discharged might not be a big problem in the case of acute conditions which resolve quickly (infections, fractures etc) but in the work that I do, medicines often need to be continued for months, sometimes years if the patient is to remain well. This was a constant challenge: destitute patients who got better while they were in the hospital relapsed promptly for lack of medicines once they got home, leading to a revolving door of repeated admissions and a steady worsening of their illness as they had more and more relapses. A few years ago, tired of this constant merry-go-round, I had approached friends in the US to donate money to set up a ‘drug bank’ in our hospital and now, every few months, I would go back to the same friends, ask for money, and then replenish the medicines. But this was a drop in the bucket compared to the need. And it was going to be no help to the woman sitting in front of me since the injection was not available in the drug bank.

I tried to think, my head throbbing, and couldn’t really come up with a good solution. Finally, I beckoned one of my junior doctors over, took out my wallet and handed her 500 rupees and told her to go get the injection from the pharmacy outside the hospital. When the injection arrived, I handed it to the woman along with a syringe and told her to find someone in her neighborhood to give her daughter the injection. I told her it would calm her daughter down for at least two to three days but that she would need continuing treatment after that and to bring her in as soon as she could.

It’s now been a couple of weeks and I haven’t heard back from her. Since our hospital, like most public hospitals, keeps no medical records, I have no way of contacting the woman. I keep hoping she will show back up in my clinic, her daughter in tow. Until then, I keep doing my clinic where we all spend most of our day trying to keep our head above water, trying to treat the poorest of the poor with our hands effectively tied behind our backs. If it were not for the generosity of the people of Pakistan as well as Pakistanis abroad, our public health system would have collapsed long ago. As it is, it continues to hang by a thread waiting for the day when our government will finally wake up to its responsibility.

The writer is a psychiatrist practicing in Lahore. He taught and practiced Psychiatry in the US for 16 years @Ali_Madeeh