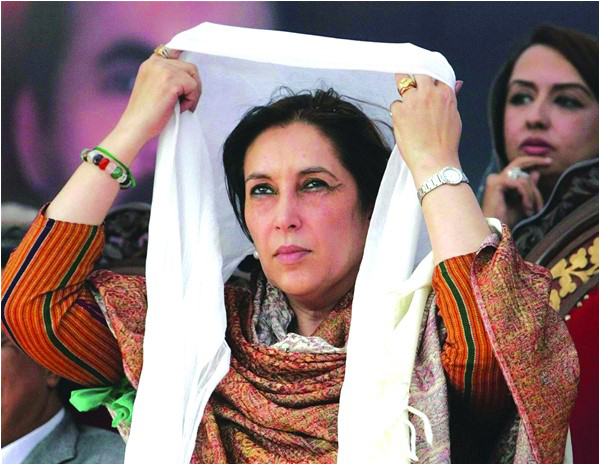

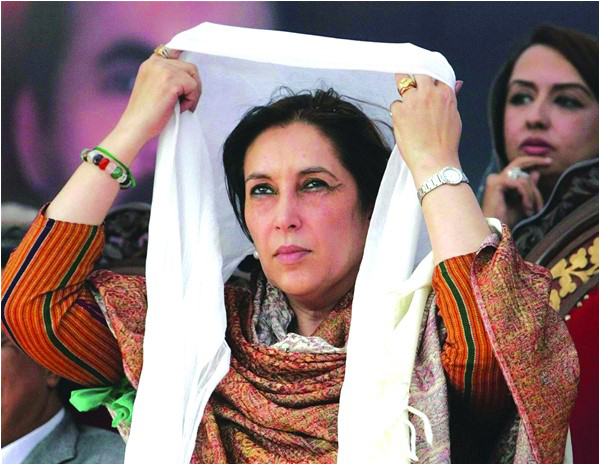

Most people can remember the exact moment that they heard the news of Benazir Bhutto’s death. You didn’t have to be a Pakistani to feel the blow. You didn’t have to be a woman to feel the pain. Benazir Bhutto’s death rocked the world, or at least the sheer violence of it did.

With a decade to her passing all sorts of tributes to her legacy are pouring in. Some paint her as a great leader others as a brave and courageous woman. But memory is selective and although I, like many others, would like to believe that her fearless campaigning just before she died was for the greater good of the country and not because she wanted to be a third time prime minister, there is more to it. The fact that she was more or less powerless even in the most powerful political position, and that it took another dictator to revisit the draconian Hudood ordinance of General Zia is something we tend to overlook now that she is gone. Though a great symbol of hope for women all over the world, in truth Benazir had little support to make the changes she really wanted. Partly due to the fact that she was not allowed to complete her term both times and partly because she did not have the support of her own party or her close family and partly because the tactile games between Pakistan’s politicians and the country’s military and intelligence would not let her be. Her assassination till date seems shrouded in unresolved mysteries.

Yet it is not just politics that her legacy is limited to. For me, she will be remembered most of all for her unapologetic attitude to womanhood. Benazir was one leader who did not give into the hyper masculinity so common of her times. Unlike Thatcher or Indira Gandhi it was her humanness and fallibility that was endearing rather than a steely reserve.

It was this humane quality that I tried to recapture when I first sat down to write a novel about women in politics. In my novel Nobody Killed Her (2017) one of the things I have tried to explore is the role of women in patriarchal, particularly Islamic, societies. And although our region is rich in female leadership, ranging from the likes of Indira Gandhi and Sonia Gandhi to Aung Sang Sui Kyi to Sheikh Hasina and Khalida Zia, it is Benazir who shattered the glass ceiling by becoming the first woman Prime Minister of a Muslim country. And the youngest. It is she who captured my imagination, as she did of many others like me. For me, she was a symbol of strength.

And this I tried to translate into the character of Rani Shah, a young woman thrown into the arena of politics as the heir to a political dynasty. But while Benazir Bhutto matured with each defeat my characters were not so lucky. Their journey was more turbulent and as they took on a life of their own, falling and rising with each twist and turn of the plot, I realised how challenging life in the public eye is for women in our part of the world. Benazir really was larger than life for I felt the real life persona of Bhutto was too strong for one character, even if loosely inspired by it. And so I created two women, each with their own sets of strength and weakness, love and hates. And so while I had taken the cue from her and the challenges I imagined she faced, the characters in my novel marched their own tune.

And why not? Benazir’s legacy is difficult for any one to live up to. Even fictional characters!

She achieved the impossible as the first woman to rise to such high office in a country that only a few years earlier had passed a law to reduce the status of a woman’s testimony in a court to half that of a man. She inspired millions of others all around the globe not just with her unbelievable ascent to power but also with her charm and wit, her political intellect and her personality that refused to cower before the toughest of opponents. For many, she is a symbol of hope, the poster person of dreamers and doers alike, inspiring not just minds but also connecting hearts – it was she who introduced the incumbent British Prime Minister Theresa May to Philip May who would become her husband. A shrewd politician and a committed family woman, Benazir Bhutto has a legacy that refused to die down with her. As veteran journalist Hasan Mujtaba said in his poem, “Woh mer kar bhi zinda hai, tum zinda ho kay bhi murdah ho (she is alive in her death; you are already dead while you live)”.

It was Benazir Bhutto’s acceptance being a woman, and a beautiful one at that, along with an elected leader that had many in a flux. In the 1980s, at a time when hyper-masculinity was the norm for women making it into a man’s world, she took on politics on her

own terms. She actualised the phrase that ‘women can have it all’ by giving birth while also being the prime minister.

She had two brief stints in office (1988-1990 and 1993-96) during which she was busier firefighting the conspiracies and allegations against her than actually accomplishing anything. Her ideas did not match that of the torturous administrative apparatus run by a bureaucracy made inefficient by a decade of Zia-ul-Haq’s military rule. She wanted better ties with India, her meetings with Rajiv Gandhi are well remembered as a means to carve a new roadmap to peace. But this, of course, did not go down well with the military establishment. She had an ambitious economic agenda but she was not able to realise much of it partly because of the friction with the army, partly because of opposition from political players such as Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM) and Nawaz Sharif and partly because of the incompetence and corruption of her own party. Most of her time in power was spent battling for survival against the machinations of those opposed to her, including the then presidents of the country, who were constantly trying to bring down her governments.

Benazir Bhutto faced constant character assassination, perpetual resistance from the mullahs who would try to rile the public proclaiming that a government headed by a woman was un-Islamic and persistent refusal by the army generals to salute a female prime minister. Yet she managed to leave behind a legacy of commitment to democracy, economic empowerment of the downtrodden and social equality that is rivalled by only the one left by her father, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto.

Whether she wanted it or not, Benazir Bhutto continues to reign on as the most gutsy Pakistani of our times, overshadowing Cricketers, Jihadists and even film stars.

As she was once quoted to have said, “I have led an unusual life. I have buried a father killed at age 50 and two brothers killed in the prime of their lives. I raised my children as a single mother when my husband was arrested and held for eight years without a conviction — a hostage to my political career.”

Many will find it hard to digest that the most ballsy Pakistani around the world should be a woman but the fact remains: she was the first one of our political leaders who challenged the Talibaan publicly even when she knew that the price of that challenge could be her own life.

And she paid the price in 2007.

Ten years on, one feels that life does intimate art. For like my novel in which an unresolved trial takes place, Benazir Bhutto’s murder too remains unsolved. Earlier this year people were greatly disappointed when the chief suspects in her case walked free prompting someone on Twitter to say, perhaps it’s true, Nobody killed her…. But unlike the novel there are no happy endings here, no free rides. One can only hope that her legacy will inspire more women to go into politics, more writers to give voice to stories of women who make a difference, more brave activists like Malala to stand up….For Benazir may have left us, but her legacy will never die. That much is at least is true.

Dr. Sabyn Javeri an award-winning short story writer and the author of bestselling novel ‘Nobody Killed Her’

With a decade to her passing all sorts of tributes to her legacy are pouring in. Some paint her as a great leader others as a brave and courageous woman. But memory is selective and although I, like many others, would like to believe that her fearless campaigning just before she died was for the greater good of the country and not because she wanted to be a third time prime minister, there is more to it. The fact that she was more or less powerless even in the most powerful political position, and that it took another dictator to revisit the draconian Hudood ordinance of General Zia is something we tend to overlook now that she is gone. Though a great symbol of hope for women all over the world, in truth Benazir had little support to make the changes she really wanted. Partly due to the fact that she was not allowed to complete her term both times and partly because she did not have the support of her own party or her close family and partly because the tactile games between Pakistan’s politicians and the country’s military and intelligence would not let her be. Her assassination till date seems shrouded in unresolved mysteries.

Yet it is not just politics that her legacy is limited to. For me, she will be remembered most of all for her unapologetic attitude to womanhood. Benazir was one leader who did not give into the hyper masculinity so common of her times. Unlike Thatcher or Indira Gandhi it was her humanness and fallibility that was endearing rather than a steely reserve.

It was this humane quality that I tried to recapture when I first sat down to write a novel about women in politics. In my novel Nobody Killed Her (2017) one of the things I have tried to explore is the role of women in patriarchal, particularly Islamic, societies. And although our region is rich in female leadership, ranging from the likes of Indira Gandhi and Sonia Gandhi to Aung Sang Sui Kyi to Sheikh Hasina and Khalida Zia, it is Benazir who shattered the glass ceiling by becoming the first woman Prime Minister of a Muslim country. And the youngest. It is she who captured my imagination, as she did of many others like me. For me, she was a symbol of strength.

And this I tried to translate into the character of Rani Shah, a young woman thrown into the arena of politics as the heir to a political dynasty. But while Benazir Bhutto matured with each defeat my characters were not so lucky. Their journey was more turbulent and as they took on a life of their own, falling and rising with each twist and turn of the plot, I realised how challenging life in the public eye is for women in our part of the world. Benazir really was larger than life for I felt the real life persona of Bhutto was too strong for one character, even if loosely inspired by it. And so I created two women, each with their own sets of strength and weakness, love and hates. And so while I had taken the cue from her and the challenges I imagined she faced, the characters in my novel marched their own tune.

For me, she will be remembered most of all for her unapologetic attitude to womanhood. Benazir was one leader who did not give into the hyper masculinity so common of her times

And why not? Benazir’s legacy is difficult for any one to live up to. Even fictional characters!

She achieved the impossible as the first woman to rise to such high office in a country that only a few years earlier had passed a law to reduce the status of a woman’s testimony in a court to half that of a man. She inspired millions of others all around the globe not just with her unbelievable ascent to power but also with her charm and wit, her political intellect and her personality that refused to cower before the toughest of opponents. For many, she is a symbol of hope, the poster person of dreamers and doers alike, inspiring not just minds but also connecting hearts – it was she who introduced the incumbent British Prime Minister Theresa May to Philip May who would become her husband. A shrewd politician and a committed family woman, Benazir Bhutto has a legacy that refused to die down with her. As veteran journalist Hasan Mujtaba said in his poem, “Woh mer kar bhi zinda hai, tum zinda ho kay bhi murdah ho (she is alive in her death; you are already dead while you live)”.

It was Benazir Bhutto’s acceptance being a woman, and a beautiful one at that, along with an elected leader that had many in a flux. In the 1980s, at a time when hyper-masculinity was the norm for women making it into a man’s world, she took on politics on her

own terms. She actualised the phrase that ‘women can have it all’ by giving birth while also being the prime minister.

She had two brief stints in office (1988-1990 and 1993-96) during which she was busier firefighting the conspiracies and allegations against her than actually accomplishing anything. Her ideas did not match that of the torturous administrative apparatus run by a bureaucracy made inefficient by a decade of Zia-ul-Haq’s military rule. She wanted better ties with India, her meetings with Rajiv Gandhi are well remembered as a means to carve a new roadmap to peace. But this, of course, did not go down well with the military establishment. She had an ambitious economic agenda but she was not able to realise much of it partly because of the friction with the army, partly because of opposition from political players such as Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM) and Nawaz Sharif and partly because of the incompetence and corruption of her own party. Most of her time in power was spent battling for survival against the machinations of those opposed to her, including the then presidents of the country, who were constantly trying to bring down her governments.

Benazir Bhutto faced constant character assassination, perpetual resistance from the mullahs who would try to rile the public proclaiming that a government headed by a woman was un-Islamic and persistent refusal by the army generals to salute a female prime minister. Yet she managed to leave behind a legacy of commitment to democracy, economic empowerment of the downtrodden and social equality that is rivalled by only the one left by her father, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto.

Whether she wanted it or not, Benazir Bhutto continues to reign on as the most gutsy Pakistani of our times, overshadowing Cricketers, Jihadists and even film stars.

As she was once quoted to have said, “I have led an unusual life. I have buried a father killed at age 50 and two brothers killed in the prime of their lives. I raised my children as a single mother when my husband was arrested and held for eight years without a conviction — a hostage to my political career.”

Many will find it hard to digest that the most ballsy Pakistani around the world should be a woman but the fact remains: she was the first one of our political leaders who challenged the Talibaan publicly even when she knew that the price of that challenge could be her own life.

And she paid the price in 2007.

Ten years on, one feels that life does intimate art. For like my novel in which an unresolved trial takes place, Benazir Bhutto’s murder too remains unsolved. Earlier this year people were greatly disappointed when the chief suspects in her case walked free prompting someone on Twitter to say, perhaps it’s true, Nobody killed her…. But unlike the novel there are no happy endings here, no free rides. One can only hope that her legacy will inspire more women to go into politics, more writers to give voice to stories of women who make a difference, more brave activists like Malala to stand up….For Benazir may have left us, but her legacy will never die. That much is at least is true.

Dr. Sabyn Javeri an award-winning short story writer and the author of bestselling novel ‘Nobody Killed Her’