In the next couple of days we will say goodbye to 2017, which was a tough year for Pakistan's foreign policy. Worryingly, there is little to suggest that 2018 will be less challenging.

Pakistan's external relations have been going through a protracted bad patch. The year 2017 was perhaps one of the most challenging years, which many are comparing with 2011, the year everything went wrong for us from Raymond Davis to OBL to Salala. This may not be an appropriate analogy, but it does point towards the gravity of what we were confronted with in the outgoing year.

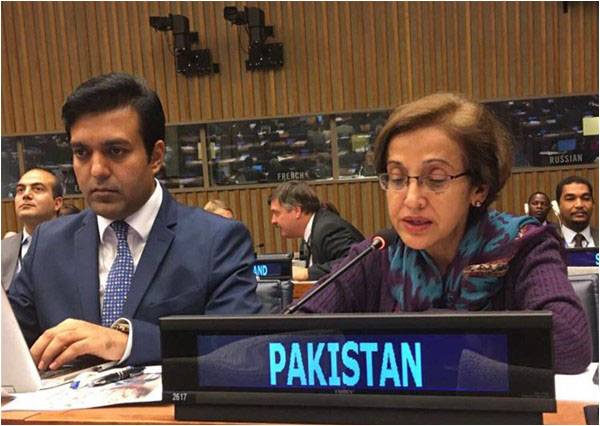

Former foreign secretary Shamshad Ahmed Khan calls it a "painful year-end". It must not have been easy at all for the Foreign Office to deal with this enormous challenge because it coincided with the change in leadership. There couldn't have been more inopportune time to change horses. Khawaja Asif became the foreign minister after the installation of Shahid Khaqqan Abbasi as the new prime minister, and only months earlier Tehmina Janjua had taken over as foreign secretary after a bruising race-a leaked letter from another contender for the post laid bare the divisions within the FO.

Relations with the US were the single biggest foreign policy challenge, which had a snowball effect on Pakistan's other regional problems, namely Afghanistan and India, although the two had their own dynamics as well. The Trump administration's harsh line on Pakistan was manifested in its policy on South Asia and Afghanistan and more lately in the National Security Strategy document. The American approach to the region, especially the strategic partnership with India, encouraged Delhi to not only persist with its policy of eschewing dialogue with Islamabad, but also continue hostilities on the Line of Control. It violated the ceasefire for a record 1,800 times this year, leading to dozens of casualties. More dangerously, India again claimed to have crossed the LoC this week. Pakistan categorically denied the Indian claim, but this would definitely take the raging tensions a notch higher.

Kabul, meanwhile, too follows the overall environment in deciding its line on Pakistan and has so far been lukewarm to Pakistani proposals for a broad-based political, military and intelligence engagement for sorting out the outstanding issues. China, the latest reports indicate, has facilitated a breakthrough in this direction at the newly instituted mechanism of the China-Afghanistan-Pakistan trilateral foreign ministers' dialogue in Beijing. But one can't be sure how real is the progress because the UK and China itself had helped Kabul and Islamabad reach similar understandings earlier in the year and they did not apparently work.

US Vice President Mike Pence's statement from Bagram Base in Afghanistan that "Pakistan has been put on notice" dimmed expectations that a nearly three-month long diplomatic effort to find common ground between Pakistan and the US after the announcement of the Afghan strategy would bear fruit. Pak-US engagement, it should be recalled, were started by VP Pence in a meeting with PM Abbasi on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly session and included visits by Foreign Minister Asif to Washington and Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and Defense Secretary Jim Mattis travelling to Pakistan for talks.

"To my mind the biggest challenge to the ingenuity of the Foreign Office came from the US announcement of its Afghanistan and South Asia Strategy followed by the US National Security Strategy, which tilts effectively the US balance towards India and threatens to denigrate relations with Pakistan," former foreign secretary Salman Bashir explains. He believes that the pressure on Pakistan was redoubled by the US on India's behest and as part of its overall China containment strategy.

Amb (retired) Aziz Khan links tensions with the US to its faltering military campaign in Afghanistan, where the Taliban look to be ascendant because of the Ghani government's poor governance, disunity among ruling allies, rampant corruption and drug trafficking. Pakistan, he says, is being made a scapegoat by the US for the failure in Afghanistan, while India is being propped up as a regional power with a bigger role in Afghanistan at the cost of Pakistan.

On the whole, Pakistan's foreign policy appeared fractured, rudderless and in fire-fighting mode throughout the year. This seemed to be the case whether it was repairing ties with Iran or the regional outreach initiated by the government soon after President Trump announced the South Asia/Afghan policy. It also applied to a review of ties with the US, and for that matter the Economic Cooperation Organization summit to beat the perceptions of regional isolation.

Lest we forget, Pakistan was also able to assume the office of the secretary general of SAARC, a sort of achievement after last year's embarrassment of not being able to host the summit because of a cancellation of the event forced by India. But little effort was made to revitalize relations with other countries in the South Asian bloc, who had joined India in boycotting the summit. This despite the fact that a foreign policy review undertaken by the government at the start of the year had stressed reconnecting with others.

Achievements on the diplomatic front were few and far and one could probably count them on one hand: a formal admission to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, election to some UN bodies, including the return to the UN Human Rights Council after the humiliating election loss in 2015, and a redemption at the Heart of Asia Ministerial Meeting in Baku where the participating countries agreed to draw up a "comprehensive list of all terrorist groups in the Heart of Asia Region." Pakistan had been uncomfortable with an earlier list adopted at last year's meeting in Amritsar that also named Pakistan-based groups Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Muhammad. In a major embarrassment for Pakistan that list was reproduced in the BRICS Summit Declaration. Adoption of the Long Term Plan of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor is of course the other bright spot.

Political uncertainty at home due to the Panama case that led to Nawaz Sharif's ouster also prevented the government from setting a clear course.

"A country's standing in the comity of nations always corresponds directly to its political, social, economic and strategic strength," maintains Amb Shamshad. "The foreign policy of a nation is nothing but an external reflection of what you are from within. No country has ever succeeded externally if it is weak and crippled domestically in political and economic terms. Even a super power, the former Soviet Union, could not survive as a super power because it was weak domestically."

There has always been a strong perception that the military has been in the foreign policy driving seat. That image was reinforced after recent developments in the country that are believed to have further tightened its grip on external relations. 'Military diplomacy' is now mentioned in press releases by the ISPR and Gen Bajwa is publicly appreciated for repairing ties with Tehran by making an unprecedented visit and creating an opening with Kabul. On the brighter side, the policy input from the military, which happens all over the world, has been formalized by regular National Security Committee meetings ever since the new government took office.

But there is a debate over who is responsible for ceding further space to the military in foreign policy realm. "For us, it's no longer important who makes our foreign policy or who runs it," notes Amb Shamshad. "Traditionally, however, with a generation of self-serving rulers always feeling insecure, a civil-military conflict has been an integral part of our body politic. If there have been instances of military interventions in the past, it was only because the civilian set-ups were invariably devoid of the requisite strategic vision or talent in their political cadres, leaving a vacuum to be filled by whosoever had the power and strategic proficiency."

He credits the army for steadfastly giving an opportunity to the civilian rulers to do their job during the last decade of civilian rule. "The disgraceful Memogate and now the surreptitious mishandling of the civil-military equation reflected in the Dawn Leaks only shows how weak and insecure the political cadres continue to feel," he believes.

Meanwhile, Amb (retired) Ashraf Jehangir Qazi is of the view that "corrupt and dishonest leadership has never been inclined to speak the truth to its own people because it knows it does not have the moral standing to educate them about diplomatic, economic and military realities. It prefers to deceive them rather than develop the country to a point where it can negotiate with India and solicit international support for its stand on a more equal and effective footing."

It would be wrong to assume that the evolving geo-political situation alone was to blame for our predicament. Many of our problems are linked to the incorrect choices made in the past, especially with regards to Afghanistan. While the world has moved on, we struggle to emerge from the mindset of the Afghan jihad days and are accused of running "sanctuaries" despite sacrificing thousands of lives in the fight against terrorism.

"Afghanistan is a complete foreign policy embarrassment," observes Amb Qazi. "We seem completely unable or unwilling to learn the obvious: the Taliban can never be a policy asset for Pakistan. Or maybe Pakistan is just too involved or weak to do what its interests in Afghanistan require it to do."

The forecast for the next year isn't very promising and one thing that can be said with surety is that it would be challenging. Amb Qazi maintains that any foreign policy improvement in 2018 "will be a genuine and welcome surprise".

FM Asif and others point towards an impending shift in foreign policy by aligning more closely with China and other regional stakeholders and reducing dependence on the US. It may sound like an interesting strategy, but peace in Afghanistan cannot be achieved by excluding Washington. A Russian initiative at the start of the year failed to make headway for the same reason.

In Amb Bashir's assessment, Pakistan and US could: "through deep conversations tide over perceptional differences and work together to achieve shared objectives. Let us not forget that Pakistan, the US and China together could be huge multipliers for development, prosperity and peace in this region and the world."

Amb Qazi calls for longer-term and sincere policy approaches. He worries, however, that it would be difficult to achieve because of a lack of "commitment and confidence" in the leadership. "Next year being an election year a decrepit political system is unlikely to produce any policy innovations," he underlines.

The writer is a freelance journalist based in Islamabad and tweets at @bokhari_mr

Pakistan's external relations have been going through a protracted bad patch. The year 2017 was perhaps one of the most challenging years, which many are comparing with 2011, the year everything went wrong for us from Raymond Davis to OBL to Salala. This may not be an appropriate analogy, but it does point towards the gravity of what we were confronted with in the outgoing year.

Former foreign secretary Shamshad Ahmed Khan calls it a "painful year-end". It must not have been easy at all for the Foreign Office to deal with this enormous challenge because it coincided with the change in leadership. There couldn't have been more inopportune time to change horses. Khawaja Asif became the foreign minister after the installation of Shahid Khaqqan Abbasi as the new prime minister, and only months earlier Tehmina Janjua had taken over as foreign secretary after a bruising race-a leaked letter from another contender for the post laid bare the divisions within the FO.

There couldn't have been more inopportune time to change horses. Khawaja Asif became the foreign minister after the installation of Shahid Khaqqan Abbasi as the new prime minister, and only months earlier Tehmina Janjua had taken over as foreign secretary after a bruising race

Relations with the US were the single biggest foreign policy challenge, which had a snowball effect on Pakistan's other regional problems, namely Afghanistan and India, although the two had their own dynamics as well. The Trump administration's harsh line on Pakistan was manifested in its policy on South Asia and Afghanistan and more lately in the National Security Strategy document. The American approach to the region, especially the strategic partnership with India, encouraged Delhi to not only persist with its policy of eschewing dialogue with Islamabad, but also continue hostilities on the Line of Control. It violated the ceasefire for a record 1,800 times this year, leading to dozens of casualties. More dangerously, India again claimed to have crossed the LoC this week. Pakistan categorically denied the Indian claim, but this would definitely take the raging tensions a notch higher.

Kabul, meanwhile, too follows the overall environment in deciding its line on Pakistan and has so far been lukewarm to Pakistani proposals for a broad-based political, military and intelligence engagement for sorting out the outstanding issues. China, the latest reports indicate, has facilitated a breakthrough in this direction at the newly instituted mechanism of the China-Afghanistan-Pakistan trilateral foreign ministers' dialogue in Beijing. But one can't be sure how real is the progress because the UK and China itself had helped Kabul and Islamabad reach similar understandings earlier in the year and they did not apparently work.

US Vice President Mike Pence's statement from Bagram Base in Afghanistan that "Pakistan has been put on notice" dimmed expectations that a nearly three-month long diplomatic effort to find common ground between Pakistan and the US after the announcement of the Afghan strategy would bear fruit. Pak-US engagement, it should be recalled, were started by VP Pence in a meeting with PM Abbasi on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly session and included visits by Foreign Minister Asif to Washington and Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and Defense Secretary Jim Mattis travelling to Pakistan for talks.

"To my mind the biggest challenge to the ingenuity of the Foreign Office came from the US announcement of its Afghanistan and South Asia Strategy followed by the US National Security Strategy, which tilts effectively the US balance towards India and threatens to denigrate relations with Pakistan," former foreign secretary Salman Bashir explains. He believes that the pressure on Pakistan was redoubled by the US on India's behest and as part of its overall China containment strategy.

Amb (retired) Aziz Khan links tensions with the US to its faltering military campaign in Afghanistan, where the Taliban look to be ascendant because of the Ghani government's poor governance, disunity among ruling allies, rampant corruption and drug trafficking. Pakistan, he says, is being made a scapegoat by the US for the failure in Afghanistan, while India is being propped up as a regional power with a bigger role in Afghanistan at the cost of Pakistan.

'Military diplomacy' is now mentioned in press releases by the ISPR and Gen Bajwa is publicly appreciated for repairing ties with Tehran by making an unprecedented visit and creating an opening with Kabul

On the whole, Pakistan's foreign policy appeared fractured, rudderless and in fire-fighting mode throughout the year. This seemed to be the case whether it was repairing ties with Iran or the regional outreach initiated by the government soon after President Trump announced the South Asia/Afghan policy. It also applied to a review of ties with the US, and for that matter the Economic Cooperation Organization summit to beat the perceptions of regional isolation.

Lest we forget, Pakistan was also able to assume the office of the secretary general of SAARC, a sort of achievement after last year's embarrassment of not being able to host the summit because of a cancellation of the event forced by India. But little effort was made to revitalize relations with other countries in the South Asian bloc, who had joined India in boycotting the summit. This despite the fact that a foreign policy review undertaken by the government at the start of the year had stressed reconnecting with others.

Achievements on the diplomatic front were few and far and one could probably count them on one hand: a formal admission to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, election to some UN bodies, including the return to the UN Human Rights Council after the humiliating election loss in 2015, and a redemption at the Heart of Asia Ministerial Meeting in Baku where the participating countries agreed to draw up a "comprehensive list of all terrorist groups in the Heart of Asia Region." Pakistan had been uncomfortable with an earlier list adopted at last year's meeting in Amritsar that also named Pakistan-based groups Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Muhammad. In a major embarrassment for Pakistan that list was reproduced in the BRICS Summit Declaration. Adoption of the Long Term Plan of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor is of course the other bright spot.

Political uncertainty at home due to the Panama case that led to Nawaz Sharif's ouster also prevented the government from setting a clear course.

"A country's standing in the comity of nations always corresponds directly to its political, social, economic and strategic strength," maintains Amb Shamshad. "The foreign policy of a nation is nothing but an external reflection of what you are from within. No country has ever succeeded externally if it is weak and crippled domestically in political and economic terms. Even a super power, the former Soviet Union, could not survive as a super power because it was weak domestically."

There has always been a strong perception that the military has been in the foreign policy driving seat. That image was reinforced after recent developments in the country that are believed to have further tightened its grip on external relations. 'Military diplomacy' is now mentioned in press releases by the ISPR and Gen Bajwa is publicly appreciated for repairing ties with Tehran by making an unprecedented visit and creating an opening with Kabul. On the brighter side, the policy input from the military, which happens all over the world, has been formalized by regular National Security Committee meetings ever since the new government took office.

But there is a debate over who is responsible for ceding further space to the military in foreign policy realm. "For us, it's no longer important who makes our foreign policy or who runs it," notes Amb Shamshad. "Traditionally, however, with a generation of self-serving rulers always feeling insecure, a civil-military conflict has been an integral part of our body politic. If there have been instances of military interventions in the past, it was only because the civilian set-ups were invariably devoid of the requisite strategic vision or talent in their political cadres, leaving a vacuum to be filled by whosoever had the power and strategic proficiency."

He credits the army for steadfastly giving an opportunity to the civilian rulers to do their job during the last decade of civilian rule. "The disgraceful Memogate and now the surreptitious mishandling of the civil-military equation reflected in the Dawn Leaks only shows how weak and insecure the political cadres continue to feel," he believes.

Meanwhile, Amb (retired) Ashraf Jehangir Qazi is of the view that "corrupt and dishonest leadership has never been inclined to speak the truth to its own people because it knows it does not have the moral standing to educate them about diplomatic, economic and military realities. It prefers to deceive them rather than develop the country to a point where it can negotiate with India and solicit international support for its stand on a more equal and effective footing."

It would be wrong to assume that the evolving geo-political situation alone was to blame for our predicament. Many of our problems are linked to the incorrect choices made in the past, especially with regards to Afghanistan. While the world has moved on, we struggle to emerge from the mindset of the Afghan jihad days and are accused of running "sanctuaries" despite sacrificing thousands of lives in the fight against terrorism.

"Afghanistan is a complete foreign policy embarrassment," observes Amb Qazi. "We seem completely unable or unwilling to learn the obvious: the Taliban can never be a policy asset for Pakistan. Or maybe Pakistan is just too involved or weak to do what its interests in Afghanistan require it to do."

The forecast for the next year isn't very promising and one thing that can be said with surety is that it would be challenging. Amb Qazi maintains that any foreign policy improvement in 2018 "will be a genuine and welcome surprise".

FM Asif and others point towards an impending shift in foreign policy by aligning more closely with China and other regional stakeholders and reducing dependence on the US. It may sound like an interesting strategy, but peace in Afghanistan cannot be achieved by excluding Washington. A Russian initiative at the start of the year failed to make headway for the same reason.

In Amb Bashir's assessment, Pakistan and US could: "through deep conversations tide over perceptional differences and work together to achieve shared objectives. Let us not forget that Pakistan, the US and China together could be huge multipliers for development, prosperity and peace in this region and the world."

Amb Qazi calls for longer-term and sincere policy approaches. He worries, however, that it would be difficult to achieve because of a lack of "commitment and confidence" in the leadership. "Next year being an election year a decrepit political system is unlikely to produce any policy innovations," he underlines.

The writer is a freelance journalist based in Islamabad and tweets at @bokhari_mr