The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party’s victory in Gujarat and Himachal Pradesh states has for the moment reinforced the fact that Prime Minister Narendra Modi is going to stay for some time.

Notwithstanding Congress party’s improved stock in the crucially fought Gujarat state, the BJP has managed to retain its position and that too for a sixth term. Gujarat was a challenge for both Modi and his arch rival, Congress’s newly elected president Rahul Gandhi. Though in terms of the power and also the skills of management, the match is unfair; Gandhi gave a tough fight to Modi that visibly made the PM nervous at some points in time. However, the results in Gujarat (not in Himachal where it is on expected lines) have also reinforced the fact that electoral politics in India continue to hold religion as an important factor. This has been reinforced time and again since the general elections in 2014 though it also is a fact that Modi’s development plank has its own takers.

But in Gujarat where the BJP had been in power for 22 years, it had become difficult for the party to retain the state. Anti-incumbency and economic measures such as the Goods and Services Tax (GST) and demonetization had their own role to play. The caste factor also was visible as three young leaders, Jignesh, Hardik and Alpesh, allied with Rahul Gandhi to give the BJP a tough fight.

The party has won but it is not the same electoral victory as we saw with the case of Uttar Pradesh in 2017 when it romped back by defeating two powerful social formations: the Samajwadi Party and Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP). That was Modi or BJP president Amit Shah’s home turf like Gujarat. It was in a way compensation for the party in lieu of Bihar where the campaign had peaked on polarization. In the case of UP, the Hindutva juggernaut worked and in Gujarat too it was probably the last resort.

Still without registering a victory, Congress managed to make a comeback in a state that was like a forbidden area. They improved its tally and did not allow the BJP to touch 100 despite the fact that party was aiming at 150. Congress got 80 and lost 15 by the margin of less than 3,000 votes. For the BJP it was a loss as its vote share came down from 60.11 percent in the 2014 Lok Sabha (general) elections to 49.3 percent. Similarly, Congress increased it from 33.45 percent in 2014 to 43 percent, of course with allies, but it registered a 41.3 percent share without allies. It certainly rings alarm bells for both the BJP and Modi himself who played the “son of the soil” card. As compared to his previous electoral battles Rahul Gandhi did manage well but he has yet to come up with a counter to Modi’s management, charisma and politics. Congress has, in the past three years, been on the receiving end and seemed reconciled with the fact that it may not come to power again as long as Modi is there. It has had the toughest time of its existence as it faces polarization politics that have worked for the BJP. Congress tried its best to shun its “secular” card but it is not working which is why Rahul’s decision to go to temples is also becoming a subject of the debate.

As of now, it is clear that Modi faced the challenge not just on the issue of development but he introduced the element of fear too when he brought Pakistan back into electoral politics. The lowest low of the politics was when he turned a private meeting attended by his predecessor Manmohan Singh at his colleague Mani Shankar Aiyar’s home into an election issue and described it as a conspiracy with Pakistan to defeat him. Aiyar had invited his long-time friend and former Pakistan foreign minister Khurshid Kasuri to his home along with Pakistan High Commissioner Sohail Mahmood and many distinguished former Indian diplomats for dinner. Modi used this as an election card and asked people whether they would vote for a party that was conspiring with Pakistan to defeat him. He also named a former Pakistan general, who according to him had tweeted in favour of Ahmed Patel, a Congress leader from Gujarat, batting for him to be the chief minister of the state. Patel becoming the CM of Gujarat is unthinkable and dragging Singh into such an unbelievable act was also in bad taste and only demonstrated how challenged Modi was on his home state.

Earlier Aiyar had made an unpleasant remark about him which he also used to emotionally exploit the voters of Gujarat, telling them that their pride had come under attack. In the past Amit Shah had used the Pakistan card in the Bihar elections. So, to polarize the voters, Pakistan has come in handy for the BJP at least this time to protect Gujarat’s “asmita (pride)”. In UP he had talked about no discrimination between “Kabristan and Shamshan” which had tilted the balance in its favour. At a UP rally he had said: “Gaon mein kabristan banta hai toh shamshan bhi ban’na chahiye.” (If a cemetery is built for Muslims in the village, then Hindu crematoria should also be built).

As with UP, the BJP did not give a single ticket to Muslims though they are 10 percent of the population. For the 50 lakh-strong Muslim community in the state, it’s nothing new – they continue to remain on the fringes of Gujarat’s electoral politics. This time Congress fielded six Muslim candidates (four won), as opposed to seven in 2012 (of which two had won). In 2007, five Muslim candidates had won, while in 2002, just three became MLAs. The BJP has never fielded a Muslim candidate in the assembly elections. The highest number was eight in 1985.

On the ground, the fact is that the status of Muslims has not changed even after the 2002 pogrom and they continue to be the second-class citizens. Not giving them any consideration is part of the policy to marginalize them and make them irrelevant in electoral politics by ensuring counter polarization. After an extensive tour to Gujarat in November, journalist Saba Naqvi wrote in The Tribune that nothing had changed for Muslims there after 2002. “There is no guilt in Gujarat about the 2002 events and Muslims continue to be viewed as suspicious, filthy, dangerous,” she wrote on November 19. The pattern was the same in UP earlier this year. The BJP had made it known before the elections that it did not need Muslims as there was not a single Muslim candidate from the party. With nearly 28% of the population, the Muslim representation had hit a new low in UP. Only 24 were elected this time, compared to 71 members in the previous assembly. Out of 24 Muslim MLAs, 15 were elected on SP tickets, seven on the BSP and two on Congress tickets.

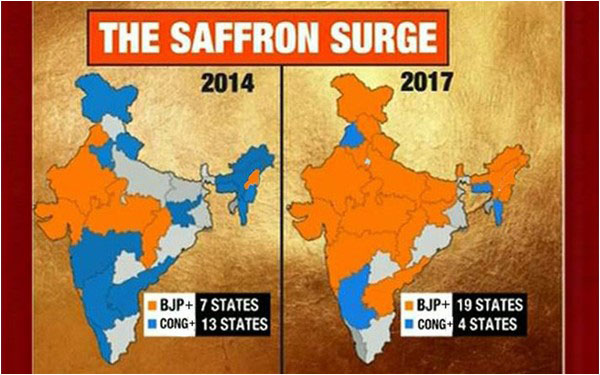

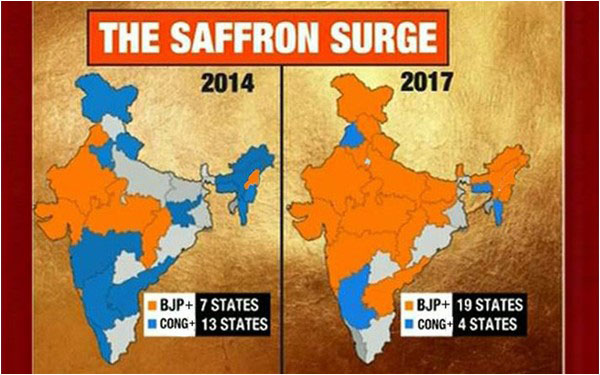

With the BJP now in power in 19 states out of 29 with their own Chief Ministers in 14, it is eyeing to “conquer” the rest. Though Gujarat has come as a warning for both BJP and Modi, the way the BJP has been using its Hindutva card along with the lure of development among the young electorate, it may not be difficult for them. The way the party has made an ordinary Hindu a “very Hindu” under the patronage of its ideological fountainhead RSS, it has reinvented the electoral wheel. Convincing the people that they had reclaimed the Hindu country that had been kept at the disposal of secularists who were indulging only in minority appeasement has helped it to spread its wings in the country. At the same time the simmering discontent on account of policies that have not worked with the economy may pose a serious challenge to Modi and his leadership. The Gujarat win was just because of Modi and not the BJP and that stock may not last long enough to win all elections.

Notwithstanding Congress party’s improved stock in the crucially fought Gujarat state, the BJP has managed to retain its position and that too for a sixth term. Gujarat was a challenge for both Modi and his arch rival, Congress’s newly elected president Rahul Gandhi. Though in terms of the power and also the skills of management, the match is unfair; Gandhi gave a tough fight to Modi that visibly made the PM nervous at some points in time. However, the results in Gujarat (not in Himachal where it is on expected lines) have also reinforced the fact that electoral politics in India continue to hold religion as an important factor. This has been reinforced time and again since the general elections in 2014 though it also is a fact that Modi’s development plank has its own takers.

But in Gujarat where the BJP had been in power for 22 years, it had become difficult for the party to retain the state. Anti-incumbency and economic measures such as the Goods and Services Tax (GST) and demonetization had their own role to play. The caste factor also was visible as three young leaders, Jignesh, Hardik and Alpesh, allied with Rahul Gandhi to give the BJP a tough fight.

The party has won but it is not the same electoral victory as we saw with the case of Uttar Pradesh in 2017 when it romped back by defeating two powerful social formations: the Samajwadi Party and Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP). That was Modi or BJP president Amit Shah’s home turf like Gujarat. It was in a way compensation for the party in lieu of Bihar where the campaign had peaked on polarization. In the case of UP, the Hindutva juggernaut worked and in Gujarat too it was probably the last resort.

Still without registering a victory, Congress managed to make a comeback in a state that was like a forbidden area. They improved its tally and did not allow the BJP to touch 100 despite the fact that party was aiming at 150. Congress got 80 and lost 15 by the margin of less than 3,000 votes. For the BJP it was a loss as its vote share came down from 60.11 percent in the 2014 Lok Sabha (general) elections to 49.3 percent. Similarly, Congress increased it from 33.45 percent in 2014 to 43 percent, of course with allies, but it registered a 41.3 percent share without allies. It certainly rings alarm bells for both the BJP and Modi himself who played the “son of the soil” card. As compared to his previous electoral battles Rahul Gandhi did manage well but he has yet to come up with a counter to Modi’s management, charisma and politics. Congress has, in the past three years, been on the receiving end and seemed reconciled with the fact that it may not come to power again as long as Modi is there. It has had the toughest time of its existence as it faces polarization politics that have worked for the BJP. Congress tried its best to shun its “secular” card but it is not working which is why Rahul’s decision to go to temples is also becoming a subject of the debate.

As of now, it is clear that Modi faced the challenge not just on the issue of development but he introduced the element of fear too when he brought Pakistan back into electoral politics. The lowest low of the politics was when he turned a private meeting attended by his predecessor Manmohan Singh at his colleague Mani Shankar Aiyar’s home into an election issue and described it as a conspiracy with Pakistan to defeat him. Aiyar had invited his long-time friend and former Pakistan foreign minister Khurshid Kasuri to his home along with Pakistan High Commissioner Sohail Mahmood and many distinguished former Indian diplomats for dinner. Modi used this as an election card and asked people whether they would vote for a party that was conspiring with Pakistan to defeat him. He also named a former Pakistan general, who according to him had tweeted in favour of Ahmed Patel, a Congress leader from Gujarat, batting for him to be the chief minister of the state. Patel becoming the CM of Gujarat is unthinkable and dragging Singh into such an unbelievable act was also in bad taste and only demonstrated how challenged Modi was on his home state.

The BJP had made it known before the elections that it did not need Muslims as there was not a single Muslim candidate from the party. With nearly 28% of the population, the Muslim representation had hit a new low in UP

Earlier Aiyar had made an unpleasant remark about him which he also used to emotionally exploit the voters of Gujarat, telling them that their pride had come under attack. In the past Amit Shah had used the Pakistan card in the Bihar elections. So, to polarize the voters, Pakistan has come in handy for the BJP at least this time to protect Gujarat’s “asmita (pride)”. In UP he had talked about no discrimination between “Kabristan and Shamshan” which had tilted the balance in its favour. At a UP rally he had said: “Gaon mein kabristan banta hai toh shamshan bhi ban’na chahiye.” (If a cemetery is built for Muslims in the village, then Hindu crematoria should also be built).

As with UP, the BJP did not give a single ticket to Muslims though they are 10 percent of the population. For the 50 lakh-strong Muslim community in the state, it’s nothing new – they continue to remain on the fringes of Gujarat’s electoral politics. This time Congress fielded six Muslim candidates (four won), as opposed to seven in 2012 (of which two had won). In 2007, five Muslim candidates had won, while in 2002, just three became MLAs. The BJP has never fielded a Muslim candidate in the assembly elections. The highest number was eight in 1985.

On the ground, the fact is that the status of Muslims has not changed even after the 2002 pogrom and they continue to be the second-class citizens. Not giving them any consideration is part of the policy to marginalize them and make them irrelevant in electoral politics by ensuring counter polarization. After an extensive tour to Gujarat in November, journalist Saba Naqvi wrote in The Tribune that nothing had changed for Muslims there after 2002. “There is no guilt in Gujarat about the 2002 events and Muslims continue to be viewed as suspicious, filthy, dangerous,” she wrote on November 19. The pattern was the same in UP earlier this year. The BJP had made it known before the elections that it did not need Muslims as there was not a single Muslim candidate from the party. With nearly 28% of the population, the Muslim representation had hit a new low in UP. Only 24 were elected this time, compared to 71 members in the previous assembly. Out of 24 Muslim MLAs, 15 were elected on SP tickets, seven on the BSP and two on Congress tickets.

With the BJP now in power in 19 states out of 29 with their own Chief Ministers in 14, it is eyeing to “conquer” the rest. Though Gujarat has come as a warning for both BJP and Modi, the way the BJP has been using its Hindutva card along with the lure of development among the young electorate, it may not be difficult for them. The way the party has made an ordinary Hindu a “very Hindu” under the patronage of its ideological fountainhead RSS, it has reinvented the electoral wheel. Convincing the people that they had reclaimed the Hindu country that had been kept at the disposal of secularists who were indulging only in minority appeasement has helped it to spread its wings in the country. At the same time the simmering discontent on account of policies that have not worked with the economy may pose a serious challenge to Modi and his leadership. The Gujarat win was just because of Modi and not the BJP and that stock may not last long enough to win all elections.