Generally speaking, the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) is considered differentia specifica in the struggle for democracy and constitutional rule in Pakistan. The last fifty years of politics has, in one way or another, been dominated by debates in favour of or in opposition to the PPP. Even, Imran Khan compared his movement to that led by PPP founder Zulfikar Ali Bhutto.

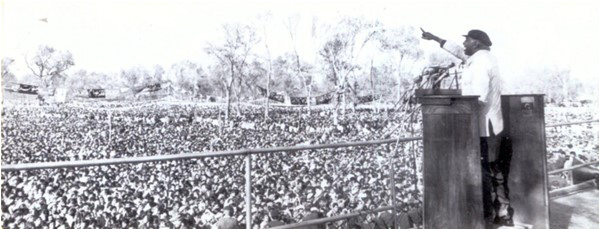

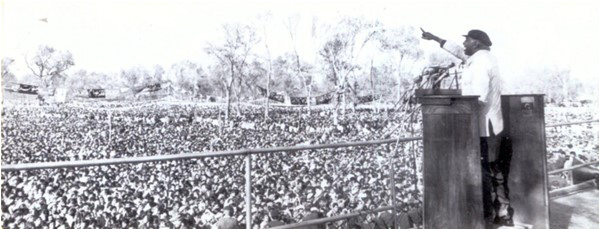

The PPP was founded by radical intelligentsia and reformist leaders in the heyday of the upheavals in 1967. The party, which spread throughout western Pakistan like wildfire, blossomed before the 1970 elections. It was a new type of party in size, complexity and function and differed from the established ones. In the 1970 election, it dominated the Western wing of the country with the slogans of ‘Roti, Kapra, Makaan’ and ‘Socialism is our economy, Islam is religion and Democracy our polity’. It was able to form governments in the center and two important provinces (Punjab and Sindh), after the succession of the Eastern wing that became Bangladesh in 1971.

Under ZAB

ZAB was able to muster all political forces on common ground for the constitution of 1973. His populism attracted all kinds of people as he attacked capitalists, the petty bourgeoisie and bureaucracy. Then he introduced many changes to the very constitution formed some years earlier to become more powerful and he attacked the opposition National Awami Party governments in Balochistan and the NWFP. Soon Bhutto found himself in a battle with enemies once the party had isolated itself from its base and succumbed to its right wing. Radicals and militants left and those who remained became apologists for the leadership’s policies.

The more the party attacked the labour and radical progressive forces in the party and outside it, the more it became a tool for the right wing. However, Bhutto’s pursuit of right wing policies could not prevent his government from falling. Eventually the movement launched by a united opposition (the Pakistan National Alliance) in the guise of Nizam-e-Mustafa, supported by anti-nationalization petty bourgeoisie forces and urban classes, paved the way for his demise. The first PPP government came to an end in a military coup d’etat led by Gen. Zia ul Haq in July 1977.

Under BB

After Bhutto’s judicial murder in April 1979, the party reorganized around women of the Bhutto family, Begum Nusrat and Benazir, while the men Shahnawaz and Murtaza resorted to terrorist activities by organizing Al Zulfikar. Sadly, like their father, both Shahnawaz and Murtaza embraced martyrdom in very different circumstances.

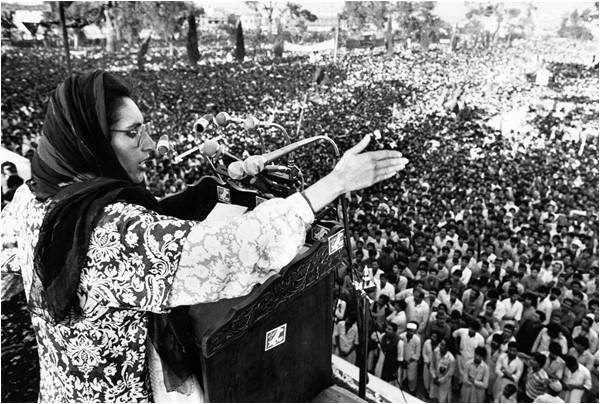

Despite the partial success of the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy launched by united opposition against the Zia dictatorship in 1981, Zia was able to rule till 1988. However, he was too weak to control the agitation. Eventually, Benazir emerged as a symbol of resistance upon her return in 1986.

Zia died in a plane crash in August 1988. By December Benazir became prime minister after a compromise with the Establishment. She led a mixed opposition against the ‘remnants of Zia ul Haq’. This was made up of the Pakistan Muslim League and a united front of parties called the Islami Jamoorhi Ittehad under Nawaz. Though Benazir tried to knock out her opponents, she courted some ‘remnants of the Zia era’ and tried to level the surface. The logic seemed to go like this: To be strong enough to attack some opponents we need to compromise with other elements. However, this policy never completely worked in the lifetimes of the Bhuttos. Like her father, Benazir was unable to earn the Establishment’s confidence. Once their control was reasonably secure—ZAB in the early 1970s, BB in the 1990s and even Zardari from 2008 to 2013—the PPP embarked on an agenda that is considered anti-Establishment. This is why the Establishment has always been skeptical about the PPP leadership. Now the PPP’s leadership might have figured out that putting pressure on the Establishment while fighting political opponents is a strategy likely to backfire.

The party under Benazir formed governments twice, from 1988 to 1990 and again from 1993 to 1996. But the Establishment toppled them. In the 1990s Benazir saw which way the wind was blowing. The party said goodbye to the policies of the 1970s and embraced a neoliberal agenda. However, under pressure from the constituency and workers, it time and again fell back on a reformist agenda. To the old guard, the current debate over the party’s position underestimates the importance of reforms and its value in the party’s history.

In the 2000s Benazir learned much. She criticized military dictator Gen. Musharraf but avoided boycotting elections. She was critical of covert support for the Afghan Taliban and realized that militancy can only be controlled through a genuine democratic government. In her speeches to American think tanks she pointed to the lack of legitimacy of the Musharraf government and assured the US that she would turn the ‘war on terror’ into a ‘people’s war on terror’.

The Lawyers Movement in 2007 laid bare the weakness of Musharraf & Co in the eyes of the international community. Benazir was able to broker a deal with Musharraf with the help of the US0. Through the National Reconciliation Ordinance she and her spouse along with a number of politicians were granted amnesty in a number cases, including those for corruption, embezzlement, money laundering, and murder. In return, she showed willingness to accept Musharraf as president. On her return in Oct. 2007 she narrowly escaped a first attack but could not survive a second on Dec. 27. Her party and allies were able to subsequently form the government in the center and in two provinces.

Under Zardari

Nonetheless, the assassination of Benazir in December 2007, paved the way for Asif Ali Zardari and his family’s domination of party affairs beyond their wildest expectations. Zardari’s resolve to continue with a ‘Pakistan Khappay’(Yes to Pakistan) policy, announced in a press conference after the assassination, never faltered and his reconciliation policies have been supported by party workers to some extent but they are worried about the future of the party. To many critics what the army junta under Zia could not do then has now been accomplished by Zardari. He and his cronies aligned themselves perfectly with the spirit of the age. A jiyala-dominated party culture has been replaced with a bureaucratic apparatus that serves the interests of specific groups.

Even the lower tier PPP leadership widely shares the sentiment of the core under Zardari that they have gained from this formula. Their reasoning is that under these policies the PPP not only completed its tenure in the Center (2008-2013) but also governed Sindh since 2008. Yet the shrinking space for it outside rural Sindh—particularly in urban Sindh and the rest of Pakistan—and organizational crisis has exposed the contradictions associated with policies pursued under Zardari & Co since 2007. Bilawal Bhutto-Zardari bears the contradictory double-barrelled surname: With the Bhutto he claims the radical history of the clan and with the Zardari he inherits the legacy of one known for corruption and reconciliation.

Right & Left

The party’s past is subject to competing and contradictory interpretations. The PPP gave a voice to those politically and economically excluded and culturally isolated. In fifty years it gained the support of the labour classes, the less privileged, minorities, and marginalized. But it can be interpreted as successful by both radicals and right wingers.

Radicals can claim that the party introduced the 1973 Constitution, introduced labour and lands reforms, nationalization of industries, and attacked capitalist power. The Right credits the party with introducing amendments to the constitution to declare Ahmadis non-Muslims, declaring Friday a holiday, banning alcohol, consolidating unity in the Islamic Ummah and organizing the Islamic Conference and setting up nuclear plants etc. It personifies the convergence of resistance and compromise; there has been no other like it.

There is no doubt that recently the PPP has suffered despite the fact that it more electoral power in rural Sindh. To the radical progressive elements, the party has sold out to the capitalists and rural elite when it is supposed to protect common people against them. One of the most tangible consequences of the PPP’s decline was seen in the by-elections results and its subsequent demise in the Punjab and KP. Whether the party could have followed a radical reformist path from 1993 to 2013 is open to debate. One only need note the successive PPP government failures as seen in the 1990s and then from 2008 to 2013 and now in Sindh since 2008. The dismal failure turned out to be an effort to install a social democratic regime by adopting the welfare playbook from the 1960s. Zardari and his close circle of politicians are full of empty threats, unable to challenge the Establishment. Many democratic intellectuals disappointed by the PPP’s pro-Establishment stance, many turn to Nawaz Sharif to fight it. There are, however, still some politically motivated enough to still consider the party a bastion of secular democratic liberalism; and there are those who want it to stay in the saddle. The show must go on.

The PPP was founded by radical intelligentsia and reformist leaders in the heyday of the upheavals in 1967. The party, which spread throughout western Pakistan like wildfire, blossomed before the 1970 elections. It was a new type of party in size, complexity and function and differed from the established ones. In the 1970 election, it dominated the Western wing of the country with the slogans of ‘Roti, Kapra, Makaan’ and ‘Socialism is our economy, Islam is religion and Democracy our polity’. It was able to form governments in the center and two important provinces (Punjab and Sindh), after the succession of the Eastern wing that became Bangladesh in 1971.

Under ZAB

ZAB was able to muster all political forces on common ground for the constitution of 1973. His populism attracted all kinds of people as he attacked capitalists, the petty bourgeoisie and bureaucracy. Then he introduced many changes to the very constitution formed some years earlier to become more powerful and he attacked the opposition National Awami Party governments in Balochistan and the NWFP. Soon Bhutto found himself in a battle with enemies once the party had isolated itself from its base and succumbed to its right wing. Radicals and militants left and those who remained became apologists for the leadership’s policies.

The more the party attacked the labour and radical progressive forces in the party and outside it, the more it became a tool for the right wing. However, Bhutto’s pursuit of right wing policies could not prevent his government from falling. Eventually the movement launched by a united opposition (the Pakistan National Alliance) in the guise of Nizam-e-Mustafa, supported by anti-nationalization petty bourgeoisie forces and urban classes, paved the way for his demise. The first PPP government came to an end in a military coup d’etat led by Gen. Zia ul Haq in July 1977.

Under BB

After Bhutto’s judicial murder in April 1979, the party reorganized around women of the Bhutto family, Begum Nusrat and Benazir, while the men Shahnawaz and Murtaza resorted to terrorist activities by organizing Al Zulfikar. Sadly, like their father, both Shahnawaz and Murtaza embraced martyrdom in very different circumstances.

Despite the partial success of the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy launched by united opposition against the Zia dictatorship in 1981, Zia was able to rule till 1988. However, he was too weak to control the agitation. Eventually, Benazir emerged as a symbol of resistance upon her return in 1986.

Zia died in a plane crash in August 1988. By December Benazir became prime minister after a compromise with the Establishment. She led a mixed opposition against the ‘remnants of Zia ul Haq’. This was made up of the Pakistan Muslim League and a united front of parties called the Islami Jamoorhi Ittehad under Nawaz. Though Benazir tried to knock out her opponents, she courted some ‘remnants of the Zia era’ and tried to level the surface. The logic seemed to go like this: To be strong enough to attack some opponents we need to compromise with other elements. However, this policy never completely worked in the lifetimes of the Bhuttos. Like her father, Benazir was unable to earn the Establishment’s confidence. Once their control was reasonably secure—ZAB in the early 1970s, BB in the 1990s and even Zardari from 2008 to 2013—the PPP embarked on an agenda that is considered anti-Establishment. This is why the Establishment has always been skeptical about the PPP leadership. Now the PPP’s leadership might have figured out that putting pressure on the Establishment while fighting political opponents is a strategy likely to backfire.

The party under Benazir formed governments twice, from 1988 to 1990 and again from 1993 to 1996. But the Establishment toppled them. In the 1990s Benazir saw which way the wind was blowing. The party said goodbye to the policies of the 1970s and embraced a neoliberal agenda. However, under pressure from the constituency and workers, it time and again fell back on a reformist agenda. To the old guard, the current debate over the party’s position underestimates the importance of reforms and its value in the party’s history.

In the 2000s Benazir learned much. She criticized military dictator Gen. Musharraf but avoided boycotting elections. She was critical of covert support for the Afghan Taliban and realized that militancy can only be controlled through a genuine democratic government. In her speeches to American think tanks she pointed to the lack of legitimacy of the Musharraf government and assured the US that she would turn the ‘war on terror’ into a ‘people’s war on terror’.

The Lawyers Movement in 2007 laid bare the weakness of Musharraf & Co in the eyes of the international community. Benazir was able to broker a deal with Musharraf with the help of the US0. Through the National Reconciliation Ordinance she and her spouse along with a number of politicians were granted amnesty in a number cases, including those for corruption, embezzlement, money laundering, and murder. In return, she showed willingness to accept Musharraf as president. On her return in Oct. 2007 she narrowly escaped a first attack but could not survive a second on Dec. 27. Her party and allies were able to subsequently form the government in the center and in two provinces.

Under Zardari

Nonetheless, the assassination of Benazir in December 2007, paved the way for Asif Ali Zardari and his family’s domination of party affairs beyond their wildest expectations. Zardari’s resolve to continue with a ‘Pakistan Khappay’(Yes to Pakistan) policy, announced in a press conference after the assassination, never faltered and his reconciliation policies have been supported by party workers to some extent but they are worried about the future of the party. To many critics what the army junta under Zia could not do then has now been accomplished by Zardari. He and his cronies aligned themselves perfectly with the spirit of the age. A jiyala-dominated party culture has been replaced with a bureaucratic apparatus that serves the interests of specific groups.

Even the lower tier PPP leadership widely shares the sentiment of the core under Zardari that they have gained from this formula. Their reasoning is that under these policies the PPP not only completed its tenure in the Center (2008-2013) but also governed Sindh since 2008. Yet the shrinking space for it outside rural Sindh—particularly in urban Sindh and the rest of Pakistan—and organizational crisis has exposed the contradictions associated with policies pursued under Zardari & Co since 2007. Bilawal Bhutto-Zardari bears the contradictory double-barrelled surname: With the Bhutto he claims the radical history of the clan and with the Zardari he inherits the legacy of one known for corruption and reconciliation.

Right & Left

The party’s past is subject to competing and contradictory interpretations. The PPP gave a voice to those politically and economically excluded and culturally isolated. In fifty years it gained the support of the labour classes, the less privileged, minorities, and marginalized. But it can be interpreted as successful by both radicals and right wingers.

Radicals can claim that the party introduced the 1973 Constitution, introduced labour and lands reforms, nationalization of industries, and attacked capitalist power. The Right credits the party with introducing amendments to the constitution to declare Ahmadis non-Muslims, declaring Friday a holiday, banning alcohol, consolidating unity in the Islamic Ummah and organizing the Islamic Conference and setting up nuclear plants etc. It personifies the convergence of resistance and compromise; there has been no other like it.

There is no doubt that recently the PPP has suffered despite the fact that it more electoral power in rural Sindh. To the radical progressive elements, the party has sold out to the capitalists and rural elite when it is supposed to protect common people against them. One of the most tangible consequences of the PPP’s decline was seen in the by-elections results and its subsequent demise in the Punjab and KP. Whether the party could have followed a radical reformist path from 1993 to 2013 is open to debate. One only need note the successive PPP government failures as seen in the 1990s and then from 2008 to 2013 and now in Sindh since 2008. The dismal failure turned out to be an effort to install a social democratic regime by adopting the welfare playbook from the 1960s. Zardari and his close circle of politicians are full of empty threats, unable to challenge the Establishment. Many democratic intellectuals disappointed by the PPP’s pro-Establishment stance, many turn to Nawaz Sharif to fight it. There are, however, still some politically motivated enough to still consider the party a bastion of secular democratic liberalism; and there are those who want it to stay in the saddle. The show must go on.