How beastly the bourgeois is,

Especially the male of the species.

(D. H. Lawrence)

In a previous offering in these pages, this writer referred to the rise of the bourgeoisie, or ‘Box-wallahs’. D. H. Lawrence, one of the greatest writers in the English language, referred to this class as “the goddamn bourgeoisie” in his poem Red Herring and separately expressed the opinion quoted above. Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, known to the world as ‘Lenin’, led an anti-monarchist, anti-capitalist Revolution: one which, its brutal evolution and eventual collapse in Russia notwithstanding, became a major source of inspiration amongst oppressed classes, races, and nations around the world.

On the other hand, both John Stuart Mill, the champion of bourgeois liberalism, and Karl Marx, the great nemesis of capitalism, applauded the transformational role of the European bourgeoisie and hailed the revolutions in Britain, America, and France that established democracy in this world. And, indeed, one cannot underrate this role. It was the early bourgeoisie, such as the Doges of Venice, or the Medici in Florence, or the Burghers of Ghent in Flanders, that spearheaded the cultural and intellectual Renaissance of Europe. Trade-route seeking explorers like Marco Polo, Christopher Columbus, Ferdinand Magellan, etc. opened up the world for all future generations. Profit-seeking innovators, like Eli Whitney, James Watt, Henry Bessemer, Carl Benz, Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, initiated and drove the Industrial Revolution that has transformed (and now threatens) the planet.

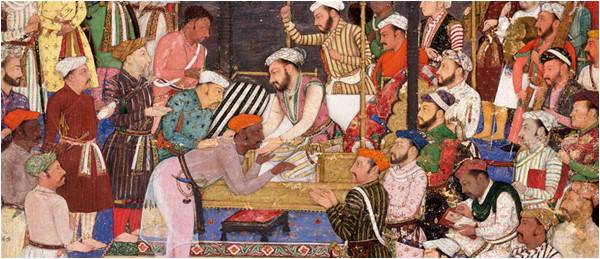

Looking at our part of the world, both Marx and Mill appreciated that the social processes in India had been different to those in Europe and elsewhere. With no organised church or hereditary barons to challenge them, kingly rulers were all-powerful. Marx labeled this system ‘Asiatic Despotism’. Clearly, no significant bourgeoisie could grow under the overpowering shadow of this despotism – a despotism which simply changed its protagonists as the British took over from the Mughals. And British Raj policy in India was consciously anti-capitalist. They encouraged no competition to their own.

Thus, the British Indian bourgeoisie remained generally limited in both numbers and economic strength. It was even more so amongst Indian Muslims. Worse, within the regions that became Pakistan, social structures were quasi-feudal with tribal holdovers – and such bourgeoisie as existed was still more pitifully puny.

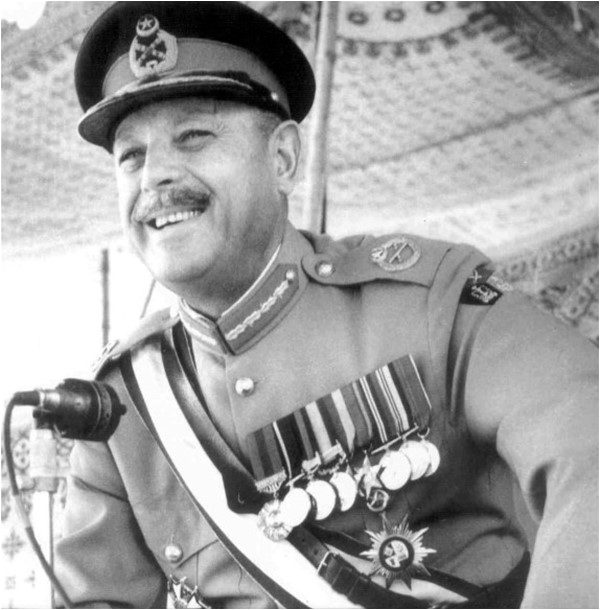

Hence, in Pakistan, this vital, transformational class lacked the numbers, institutional strength or consciousness to mould the country into a dynamic, democratic nation. Such bourgeoisie as exists (textile millers and other industrialists) is small-time compared to its counterparts beyond our borders. A timid class, it was primarily formed during the Ayubian ‘golden era’ within the crucible of bureaucratic patronage, with the help of permits, SROs, and artificial exchange rates. It was always kept within bounds by the military-bureaucratic oligarchy.

A timid class, it was primarily formed during the Ayubian 'golden era' within the crucible of bureaucratic patronage, with the help of permits, SROs, and artificial exchange rates

Far from playing the role of a transformative ‘national bourgeoisie’, building powerful industrial and financial empires, its investments have generally remained restricted in size and scale. It did not invest in substantial infrastructure projects or large-capacity plants capable of competing on world markets. It has consistently failed to invest in the development of the two most vital elements of a business: brand building and human resource development. It has singularly failed to find a role for itself in the globalised value chain.

Moreover, we have seen how the profits made by our industrial barons were siphoned out of the economy for investment into real estate in Manhattan, Mayfair, and Dubai or tossed onto Stock Exchanges in New York, London, Singapore, even Mumbai.

The countervailing elite group, the traditionally powerful white-collar gentry, comprises the professional middle classes: civil and military bureaucrats, doctors, lawyers, business professionals, judges, journalists and so on. Organic descendants of the ‘Salariat’ who led the Pakistan movement, it is they who comprise the civil-military-judicial oligarchy, or articulate their interests through that oligarchy. This is the social stratum that houses the Leviathan commonly referred to as the ‘Establishment’, whose backbone is the civilian bureaucracy and whose forceful arm is the military. These oligarchs frequently lack political literacy, leaning towards pragmatism and a belief in so-called technocratic solutions. Those who do have well-articulated political opinions tend to be conservative, with views ranging rightward from elitist pseudo-liberalism to rock-solid Islamism. When elections are held, they seldom vote, believing that “corrupt, damned politicians” are incapable of running things. When coups d’état occur, they feed laddoos to one another.

But that is not where it ends. Alongside the well-heeled gentlemen and ladies of the professional classes are the less fashion-conscious middle and lower business classes. These are traders and small industrialists, workshop owners and shopkeepers, cotton ginners, rice huskers, agricultural merchants and middlemen — all those who are in fact keeping the wheels of business moving — and those members of the educated petit bourgeoisie linked with them. This is a vital class, from amongst whom a real national bourgeoisie could have emerged if a Pakistani equivalent of Nehru and Patel’s Indian National Congress could have been wished into existence.

Back in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the left-wing PPP (and the Awami League in what is now Bangladesh), couching its campaign in populist-socialist terms, was able to excite the anti-elite instincts of this incipient national bourgeoisie and mobilise them politically.

But the democratic left, since those heady days, has managed to wish itself out of existence. Today, the business bourgeoisie of Pakistan is politically fragmented. At one extreme, misled by pseudo-Islamic slogans, many of its members actively support jihadist enterprises. Also on the right, this is where the supporters of the religio-political parties, the 10 percent that always show up at election time, are to be found. The MQM and the ANP, in their respective provincial strongholds, draw their support from these, as do the various avowedly ethnic sub-national parties who articulate regional grievances.

Mian Nawaz Sharif and his faction of the Muslim League have actively and successfully managed to cultivate and mobilise this middle and small bourgeoisie; however, the PMLN’s support remains mostly confined to Punjab. In any case, as we have seen, Mian-Sahib and his followers are in an open clash with the bureaucratic-military-judicial combine. How this conflict develops and is resolved carries immense consequences for the future of us all. It is, in my view, particularly important for commentators and analysts to be clear-eyed and objective about the developments taking place: citizens must remain properly informed.