Since the determined and focused military operations on terrorists and their hideouts across Pakistan during the last three years in particular, much seems to be changing. For instance, the frequency and number of explosions, target killings, and suicide bombings has dramatically diminished. Life has begun to feel normal. Schools, colleges and universities as well as markets and bazaars, offices and prayer houses, buses, trains and airplanes are now crowded with confident-looking people. The reign of terrorism unleashed in the name of Islam and jihad by General Zia-ul-Haq and his collaborators seemed to be packing off.

This was interrupted by a terrorist group that struck in Karachi, sending the message that the “war against terror” was unlikely to end soon, and centres of higher learning in Pakistan have the potential to be turned into jihadi recruiting grounds.

It was on the first day of Eid-ul-Azha, on September 2, 2017, when Khawaja Izharul Hassan, leader of the opposition in the Sindh Assembly and a senior leader of the Karachi-based political party, the Muttahida Qaumi Movement-Pakistan, was fired upon. The attack took place near a mosque in the lower- middle class locality of the Central Buffer Zone district. He had just said his Eid prayers and was hugging members of the congregation. While he escaped unhurt, one of his security guards and a 10-year-old boy were killed. Four others were wounded in the attack. The assailants had reportedly come on three motorcycles and were in police uniforms. Four of the assailants opened fire on the MQM leader. During an exchange of fire, one of the attackers was killed, while others managed to escape.

While the incident itself was horrific enough, it was the identity of the assailants that multiplied the worries of government and security officials and average people. According to media reports, a man identified as Abdul Karim Sarosh Siddiqui was believed to be the mastermind of the attack. Siddiqui was a student of the University of Karachi’s Applied Physics department in 2011, and his father is a retired professor from the same institution. Another attacker, suspect Hassaan was identified as a lab technician at the Dawood University of Engineering & Technology.

The involvement of educated young men in a terrorist attack alarmed teachers, students, parents, and government and security officials. This attack was not the first of its kind.

For instance, in April 2017, Naureen Leghari, a student of Liaquat University of Medical & Health Sciences in Jamshoro, Sindh, was arrested by the police and intelligence agencies in Lahore. She had reportedly visited Syria and obtained military training there. She is also alleged to have joined the militant Islamic State group. Saad Aziz, who was involved in the killing of Shia-Ismailis in Karachi in 2005 was a BBA graduate from the reputed Institute of Business Administration. His accomplices Shahid Yusuf (an electronics engineer), Adil Masood (Fordham University graduate), and Ali Rehman (an engineer) were all university educated. And a few years earlier, in 2002, Daniel Pearl, the South Asia correspondent for the Wall Street Journal was murdered in Karachi. Those involved were educated men. One of the prime suspects, Omar Saeed Sheikh, who was later convicted by an anti-terrorism court, had studied at the London School of Economics.

Besides their involvement in such high-profile incidents, young people from universities and engineering and medical colleges are feared to be involved in terrorist activities. The very fact that a number of young people arrested in recent years are alleged to be either possessing university or professional degrees or have been admitted to or enrolled at such institutions has aroused considerable concern in these circles.

Strange trends

The most striking revelation in certain sections of the press is that Urdu-speaking youth is becoming involved in acts of terrorism, and the insinuation is that the University of Karachi might be producing terrorists. Small wonder therefore that soon after the attack on the MQM-P leader, a rumour started making the rounds that the security agencies wanted access to student and staff data, and had called for enhanced security preparedness to counter terrorist activities on campus.

Consequently, public universities in Karachi such as KU and NED University of Engineering & Technology held meetings with their staff members, reviewed the security measures taken so far, and expressed reluctance to share student data with the security agencies. Meanwhile, the media reported that the security agencies had never asked for any such data. The media as well as civil society organizations started to call for long-term measures to curb and control the influence of jihadi thinking, literature and organizations, changes in curriculum, re-invigoration of extra-curricular activities, enhanced vigilance on campuses and focused attention and supervision of parents. It was also suggested that students unions should be revived.

Solutions

It is undeniable that a number of measures, both short and long term, need to be taken to improve the situation on campuses, ameliorate worries and fears in the student body and with their parents, and university staff. It is also important to contain the arrogance and display of power, especially by those managing security, on campuses, and subdue fear-mongers.

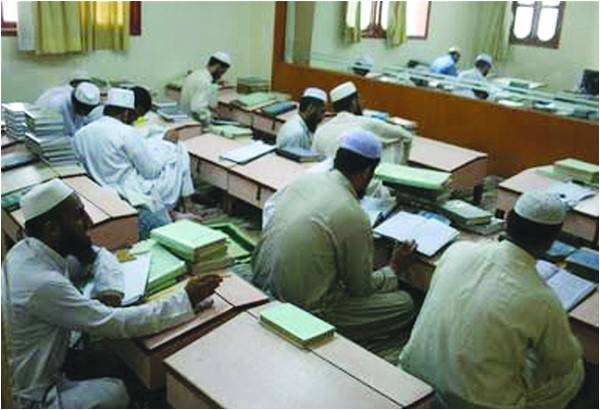

In this context, it is important to note that there is a vast difference between universities and colleges and jihadi seminaries. Seminaries generally discourage open discussion on both critical and trivial issues. They teach religion and history in order to develop a certain mindset. They resent critical thinking, promote conformism and pamper religious bigotry and extremism. In their religious zeal, a number of these seminaries encourage brainwashing.

But this is not possible in universities and colleges, where students and teachers come from diverse backgrounds, cherish and nourish different social and political ideas, and study different modern subjects, debate each other in the class and outside and welcome new ideas. However stubborn, insistent and persistent a teacher may be, he or she simply cannot succeed in brainwashing a student. A university or a college classroom is a totally different kind of intellectual space and it cannot be equated with the stifling and suffocating intellectual space of madrassas. A university, as such, can never be a brainwashing factory as seminaries can be.

Furthermore, there is hardly any need for fear-mongering even if a few terrorists are discovered to either possess a university or professional degree or are found to be former students. They can be enrolled or even work on campuses. Terrorist groups, outfits and organizations may themselves plant their members in such institutions as students or staff, because enrollment at university or college or employment depends on academic credentials and performance in an interview.

Perhaps we can be less alarmist and more composed if we look at the issue from another angle. It is, for example, in everybody’s knowledge that some terrorists were found to be belonging to the military, police, and other government institutions. Even after this information emerged, neither the government, nor the media and common citizens panicked and never said that these organizations had been converted into jihadi seminaries or terrorist factories.

Again, it needs to be appreciated that de-radicalization of a campus is not the issue. Universities and colleges are not radicalized just as the military, police, law-enforcing agencies and government offices are not radicalized even if some black sheep may exist in them. The real issue is the de-securitization of campuses, and lowering of dependence on government-managed security there. Any further securitization in the name of security would further impoverish finance-starving universities and colleges and eventually convert these institutions of higher learning into graveyards of critical thinking, fresh ideas, innovation, and movements for political and social change. This is exactly what the religious extremists and terrorist organizations want to achieve.

It is equally important that government security forces on campuses should be curtailed gradually and replaced by a university’s own security force. Again, the visibility of a security arrangement should be minimal as men roaming around with guns instills fear, cripples the independence of youth and enslaves their spirit. It is clear that the revival of students unions on campus and student activism can go a long way to making universities more secure.

Likewise, universities needs teachers with original and innovative ideas, who can boldly articulate their views on any issue at any forum. The yardstick to judge the potential of a teacher should be integrity, critical temper, and the courage to speak to power and not be enamoured by the weight of paper degrees or opportunism. And of course the Vice Chancellor has to be a philosopher, an intellectual leader, rather than a mediocre bureaucrat focusing on managing local crises from moment to moment. Lastly, universities and colleges need to be reconnected to society in their immediate environs and also to the world at large.

Since the fight against extremism and religious bigotry cannot be won by weapons and securitization alone, it is important that universities and colleges are treated as nurseries for leadership and fresher and bold ideas and solutions.

Professor Syed Sikander Mehdi is director for Academics and Registrar of Malir University of Science and Technology, Karachi. He can be reached at sikander.mehdi@gmail.com

This was interrupted by a terrorist group that struck in Karachi, sending the message that the “war against terror” was unlikely to end soon, and centres of higher learning in Pakistan have the potential to be turned into jihadi recruiting grounds.

It was on the first day of Eid-ul-Azha, on September 2, 2017, when Khawaja Izharul Hassan, leader of the opposition in the Sindh Assembly and a senior leader of the Karachi-based political party, the Muttahida Qaumi Movement-Pakistan, was fired upon. The attack took place near a mosque in the lower- middle class locality of the Central Buffer Zone district. He had just said his Eid prayers and was hugging members of the congregation. While he escaped unhurt, one of his security guards and a 10-year-old boy were killed. Four others were wounded in the attack. The assailants had reportedly come on three motorcycles and were in police uniforms. Four of the assailants opened fire on the MQM leader. During an exchange of fire, one of the attackers was killed, while others managed to escape.

Government security forces on campuses should be curtailed gradually and replaced by a university's own security force

While the incident itself was horrific enough, it was the identity of the assailants that multiplied the worries of government and security officials and average people. According to media reports, a man identified as Abdul Karim Sarosh Siddiqui was believed to be the mastermind of the attack. Siddiqui was a student of the University of Karachi’s Applied Physics department in 2011, and his father is a retired professor from the same institution. Another attacker, suspect Hassaan was identified as a lab technician at the Dawood University of Engineering & Technology.

The involvement of educated young men in a terrorist attack alarmed teachers, students, parents, and government and security officials. This attack was not the first of its kind.

For instance, in April 2017, Naureen Leghari, a student of Liaquat University of Medical & Health Sciences in Jamshoro, Sindh, was arrested by the police and intelligence agencies in Lahore. She had reportedly visited Syria and obtained military training there. She is also alleged to have joined the militant Islamic State group. Saad Aziz, who was involved in the killing of Shia-Ismailis in Karachi in 2005 was a BBA graduate from the reputed Institute of Business Administration. His accomplices Shahid Yusuf (an electronics engineer), Adil Masood (Fordham University graduate), and Ali Rehman (an engineer) were all university educated. And a few years earlier, in 2002, Daniel Pearl, the South Asia correspondent for the Wall Street Journal was murdered in Karachi. Those involved were educated men. One of the prime suspects, Omar Saeed Sheikh, who was later convicted by an anti-terrorism court, had studied at the London School of Economics.

Besides their involvement in such high-profile incidents, young people from universities and engineering and medical colleges are feared to be involved in terrorist activities. The very fact that a number of young people arrested in recent years are alleged to be either possessing university or professional degrees or have been admitted to or enrolled at such institutions has aroused considerable concern in these circles.

Seminaries do not encourage critical thinking like universities do. Brainwashing is not possible in universities where students and teachers come from diverse backgrounds, debate each other in class and outside

Strange trends

The most striking revelation in certain sections of the press is that Urdu-speaking youth is becoming involved in acts of terrorism, and the insinuation is that the University of Karachi might be producing terrorists. Small wonder therefore that soon after the attack on the MQM-P leader, a rumour started making the rounds that the security agencies wanted access to student and staff data, and had called for enhanced security preparedness to counter terrorist activities on campus.

Consequently, public universities in Karachi such as KU and NED University of Engineering & Technology held meetings with their staff members, reviewed the security measures taken so far, and expressed reluctance to share student data with the security agencies. Meanwhile, the media reported that the security agencies had never asked for any such data. The media as well as civil society organizations started to call for long-term measures to curb and control the influence of jihadi thinking, literature and organizations, changes in curriculum, re-invigoration of extra-curricular activities, enhanced vigilance on campuses and focused attention and supervision of parents. It was also suggested that students unions should be revived.

Solutions

It is undeniable that a number of measures, both short and long term, need to be taken to improve the situation on campuses, ameliorate worries and fears in the student body and with their parents, and university staff. It is also important to contain the arrogance and display of power, especially by those managing security, on campuses, and subdue fear-mongers.

In this context, it is important to note that there is a vast difference between universities and colleges and jihadi seminaries. Seminaries generally discourage open discussion on both critical and trivial issues. They teach religion and history in order to develop a certain mindset. They resent critical thinking, promote conformism and pamper religious bigotry and extremism. In their religious zeal, a number of these seminaries encourage brainwashing.

But this is not possible in universities and colleges, where students and teachers come from diverse backgrounds, cherish and nourish different social and political ideas, and study different modern subjects, debate each other in the class and outside and welcome new ideas. However stubborn, insistent and persistent a teacher may be, he or she simply cannot succeed in brainwashing a student. A university or a college classroom is a totally different kind of intellectual space and it cannot be equated with the stifling and suffocating intellectual space of madrassas. A university, as such, can never be a brainwashing factory as seminaries can be.

Furthermore, there is hardly any need for fear-mongering even if a few terrorists are discovered to either possess a university or professional degree or are found to be former students. They can be enrolled or even work on campuses. Terrorist groups, outfits and organizations may themselves plant their members in such institutions as students or staff, because enrollment at university or college or employment depends on academic credentials and performance in an interview.

Perhaps we can be less alarmist and more composed if we look at the issue from another angle. It is, for example, in everybody’s knowledge that some terrorists were found to be belonging to the military, police, and other government institutions. Even after this information emerged, neither the government, nor the media and common citizens panicked and never said that these organizations had been converted into jihadi seminaries or terrorist factories.

Again, it needs to be appreciated that de-radicalization of a campus is not the issue. Universities and colleges are not radicalized just as the military, police, law-enforcing agencies and government offices are not radicalized even if some black sheep may exist in them. The real issue is the de-securitization of campuses, and lowering of dependence on government-managed security there. Any further securitization in the name of security would further impoverish finance-starving universities and colleges and eventually convert these institutions of higher learning into graveyards of critical thinking, fresh ideas, innovation, and movements for political and social change. This is exactly what the religious extremists and terrorist organizations want to achieve.

It is equally important that government security forces on campuses should be curtailed gradually and replaced by a university’s own security force. Again, the visibility of a security arrangement should be minimal as men roaming around with guns instills fear, cripples the independence of youth and enslaves their spirit. It is clear that the revival of students unions on campus and student activism can go a long way to making universities more secure.

Likewise, universities needs teachers with original and innovative ideas, who can boldly articulate their views on any issue at any forum. The yardstick to judge the potential of a teacher should be integrity, critical temper, and the courage to speak to power and not be enamoured by the weight of paper degrees or opportunism. And of course the Vice Chancellor has to be a philosopher, an intellectual leader, rather than a mediocre bureaucrat focusing on managing local crises from moment to moment. Lastly, universities and colleges need to be reconnected to society in their immediate environs and also to the world at large.

Since the fight against extremism and religious bigotry cannot be won by weapons and securitization alone, it is important that universities and colleges are treated as nurseries for leadership and fresher and bold ideas and solutions.

Professor Syed Sikander Mehdi is director for Academics and Registrar of Malir University of Science and Technology, Karachi. He can be reached at sikander.mehdi@gmail.com