In 2010, three young men were killed in an encounter in a border area called Machil that falls in Kupwara district. Their case came to be known as the Machil encounter and today, its outcome qualifies it as a test case for the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act.

Five years later, by 2015, an army court-martial had awarded five army men, including a colonel, life imprisonment for faking the Machil encounter. The decision was welcomed in Kashmir as it seemingly reversed the practice of defending the army’s human rights violations. Over 27 years of conflict, armed forces personnel have hardly ever been punished, even when they have clearly violated human rights. However, even if action was taken against them, the punishments were either struck down by the civilian courts or by the army’s higher-ups. But with the Machil case, it seemed as if justice was done. But those hopes were short-lived since the Armed Forces Tribunal (AFT) suspended the sentence and granted all five bail this July.

The case

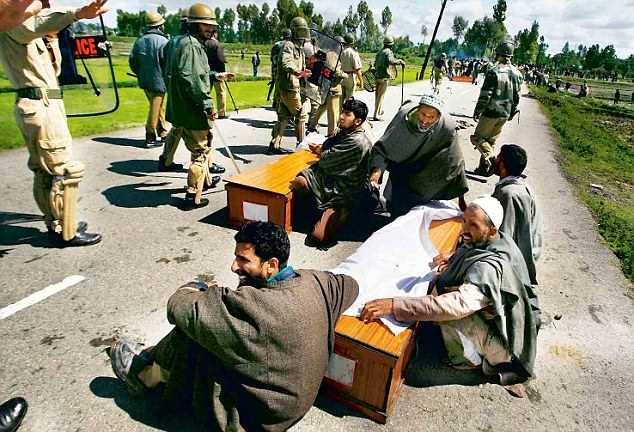

The Machil fake encounter took place on April 29, 2010 in Sona Pindi, Machil sector. Shazad Khan, 27, Shafi Lone, 19 and Riyaz Lone, 20 of Nadihal village in Rafiabad were killed. Soon after the news broke, Kashmir went up in flames, leading to four months of unrest that left 120 people dead in firing by police and Central Reserve Police Force. The Omar Abdullah government could not get a grip on the situation.

The police gathered irrefutable evidence. The army’s court of inquiry began in July 2010 with the court-martial proceedings starting in December 2013. It took the bulk of evidence from the police investigations into account. The police had filed a chargesheet against 11 people.

The case was meticulously followed and culminated in the sentence to the five army men: the then four Rajputana Rifles Commanding Officer Col Dinesh Pathania, Captain Upendra (holding the field rank of Major), Havaldar Devendra Kumar, Lance Naik Lakhmi and Lance Naik Arun Kumar. In September 2015, the then Northern Army Commander Lt General DS Hooda confirmed the sentence on the basis of unequivocal advice of his legal headquarters. This was indeed the first case (of such a magnitude) in which the army took upon itself the responsibility of punishing the guilty in this manner, though there are earlier instances of punishments given out to erring officers.

Hopes dashed

This July, however, all sense of justice prevailing was dashed when the AFT suspended the punishment. “There was absolutely no justification for a civilian to be present at such a forward formation near LoC, that too during the night when the infiltration from across the border was high,’’ stated the AFT, comprising Justice VK Shali and Lt General SK Singh. This was stated, despite the fact that the three men were lured by an army source to Machil near the LoC on the pretext of giving them jobs.

Another frivolous argument created the “Pathan suit” theory. The AFT said that they could not rule out the possibility that the accused persons were terrorists who had infiltrated the border or were crossing over to the other side. They based this argument on the fact that they were wearing ‘Pathan suits’ or shalwar kameez, which they said terrorists wore. They even got the date of the fake encounter wrong, mentioning October instead of April.

The families of the victims have threatened to hang themselves. Not only is Kashmir dismayed over this travesty of justice but those associated with the process of taking the case to its logical conclusion are also disturbed. At least two army officers told The Indian Express’s Sushant Singh that they were upset with the decision. “I can’t comment on the AFT ruling,” Lt Gen (retd) DS Hooda told Singh as well. “It’s not really my place to do so. However, the case went through the whole process of the military judicial system over a period of more than five years. There are well established practices which were followed and any criticism of the Army is not really justified.” (August 3, 2017)

The problem

Machil is part of a pattern of denying justice to victims of atrocities by personnel of the armed forces—despite due process having taken place. The army plays the “veto” card since it enjoys unbridled power and absolute cover in getting away with crimes which, if tried in a civil court, would merit severe punishment.

A classic example is the infamous Pathribal fake encounter in which five officers, including a colonel who later retired as a major general, were found guilty of staging an encounter and killing five civilians in March 2000, following the massacre of 35 Sikhs in Chattisinghpora in South Kashmir. The massacre coincided with President Bill Clinton’s visit to India. The Central Bureau of Investigation had clinching evidence against the officers but in this case the Government of India refused permission to prosecute. The case went up to the Supreme Court, which gave the army the choice of holding a court-martial or being tried in a civil court. The army decided to hold a court of inquiry and disposed of the case!

The power to choose the course of inquiry which has been vested with the army has played a significant role in thwarting justice in such cases. Section 125 of the Army Act, 1950 allows it to choose between a regular criminal court and court-martial. It has continued to shield army personnel.

The section reads as follows: “Section 125. Choice between criminal court and court-martial. When a criminal court and a court-martial have each jurisdiction in respect of an offence, it shall be in the discretion of the officer commanding the army, army corps, division or independent brigade in which the accused person is serving or such other officer as may be prescribed to decide before which court the proceedings shall be instituted, and, if that officer decides that they should be instituted before a court-martial, to direct that the accused person shall be detained in military custody.” Essentially, the personnel can choose the forum, and in most cases they choose the court-martial.

Ironically, erring army personnel choose civil courts when it comes to accidents, as they fear sterner punishment from army courts on grounds of violating discipline. There was, for example, an army major who was dismissed from service with a sentence of seven years by the army court-martial. He later went to civil court. Captain Ravinder Singh Tewatia and Special Police Officer Bharat Bhushan were found guilty of raping two women at their home in Banihal, Doda on February 14, 2000. Two separate charge sheets were filed in the court of the chief judicial magistrate Banihal. Finally, the court-martial confirmed the crime and the captain was punished. He went to the district court but it refused to provide relief, following which he challenged the ruling in the high court. The high court set aside the court-martial judgment but the army appealed before a division bench where the case is pending.

The victims

The biggest hurdle to justice in such cases is that both the Army and Border Security Force Acts are silent about the right to defence of the victims in army courts, an example of which is the Pathribal case. No relative was allowed to present their side. There is absolutely no provision for the victims to plead their case.

There are rare cases like that of Major Rehman Hussain who was dismissed from service on charges of rape in Handwara in 2005. A comprehensive report “Structure of Violence” compiled by the International People’s Tribunal on Human Rights and Justice and Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (released in Sept 2015) points out that:

Military Tribunals compromise the basic principle of equality before the law or equal treatment before the law. While the Pathribal victims wait for justice, we know it is only when court-martials are replaced by an open, transparent and fair trial in a regular independent court system, can the victims of armed forces atrocities in Kashmir even begin to expect justice.

One view has been that the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act gives impunity to army personnel in conflict areas. But in reality, it is the Act and certain sections of the Code of Criminal Procedure along with government orders that give full cover to erring army officers. These laws allow them to go unpunished for violating human rights. Even though the state government fulfilled its job of proving that the three civilians were innocent, the AFT had the last word in labelling them “terrorists” and letting the guilty out of jail.

Consider these sections of the Code of Criminal Procedure and the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act:

(i) Section 45(1)—Notwithstanding anything contained in Sections 41 to 44 (both inclusive), no member of the armed forces of the union shall be arrested for anything done or purported to be done by him in the discharge of his official duties except after obtaining the consent of the central government.

(ii) Section 197(2)—No court shall take cognisance of any offence alleged to have been committed by any member of the armed forces of the union while acting or purporting to act in the discharge of his official duty, except with the previous sanction of the central government.

(iii) Section 7, Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA)—Protection of persons acting in good faith under this act—No prosecution, suit or other legal proceeding shall be instituted, except with the previous sanction of the central government, against any person in respect of anything done or purported to be done in exercise of the powers conferred by this Act.

It is interesting that so far the AFSPA has not been invoked as there seems to be no need in view of the Army Act covering its interests.

The writer is a senior journalist based in Srinagar (Kashmir) and can be reached at shujaat7867@gmail.com

Five years later, by 2015, an army court-martial had awarded five army men, including a colonel, life imprisonment for faking the Machil encounter. The decision was welcomed in Kashmir as it seemingly reversed the practice of defending the army’s human rights violations. Over 27 years of conflict, armed forces personnel have hardly ever been punished, even when they have clearly violated human rights. However, even if action was taken against them, the punishments were either struck down by the civilian courts or by the army’s higher-ups. But with the Machil case, it seemed as if justice was done. But those hopes were short-lived since the Armed Forces Tribunal (AFT) suspended the sentence and granted all five bail this July.

Over 27 years of conflict, armed forces personnel have hardly ever been punished, even when they have clearly violated human rights. However, even if action was taken against them, the punishments were either struck down by the civilian courts or by the army's higher-ups

The case

The Machil fake encounter took place on April 29, 2010 in Sona Pindi, Machil sector. Shazad Khan, 27, Shafi Lone, 19 and Riyaz Lone, 20 of Nadihal village in Rafiabad were killed. Soon after the news broke, Kashmir went up in flames, leading to four months of unrest that left 120 people dead in firing by police and Central Reserve Police Force. The Omar Abdullah government could not get a grip on the situation.

The police gathered irrefutable evidence. The army’s court of inquiry began in July 2010 with the court-martial proceedings starting in December 2013. It took the bulk of evidence from the police investigations into account. The police had filed a chargesheet against 11 people.

The case was meticulously followed and culminated in the sentence to the five army men: the then four Rajputana Rifles Commanding Officer Col Dinesh Pathania, Captain Upendra (holding the field rank of Major), Havaldar Devendra Kumar, Lance Naik Lakhmi and Lance Naik Arun Kumar. In September 2015, the then Northern Army Commander Lt General DS Hooda confirmed the sentence on the basis of unequivocal advice of his legal headquarters. This was indeed the first case (of such a magnitude) in which the army took upon itself the responsibility of punishing the guilty in this manner, though there are earlier instances of punishments given out to erring officers.

Hopes dashed

This July, however, all sense of justice prevailing was dashed when the AFT suspended the punishment. “There was absolutely no justification for a civilian to be present at such a forward formation near LoC, that too during the night when the infiltration from across the border was high,’’ stated the AFT, comprising Justice VK Shali and Lt General SK Singh. This was stated, despite the fact that the three men were lured by an army source to Machil near the LoC on the pretext of giving them jobs.

Another frivolous argument created the “Pathan suit” theory. The AFT said that they could not rule out the possibility that the accused persons were terrorists who had infiltrated the border or were crossing over to the other side. They based this argument on the fact that they were wearing ‘Pathan suits’ or shalwar kameez, which they said terrorists wore. They even got the date of the fake encounter wrong, mentioning October instead of April.

The families of the victims have threatened to hang themselves. Not only is Kashmir dismayed over this travesty of justice but those associated with the process of taking the case to its logical conclusion are also disturbed. At least two army officers told The Indian Express’s Sushant Singh that they were upset with the decision. “I can’t comment on the AFT ruling,” Lt Gen (retd) DS Hooda told Singh as well. “It’s not really my place to do so. However, the case went through the whole process of the military judicial system over a period of more than five years. There are well established practices which were followed and any criticism of the Army is not really justified.” (August 3, 2017)

The Armed Forces Tribunal freed the men on bail in July, saying the victims were terrorists because they were wearing 'Pathan suits' or shalwar kameezes and had infiltrated the border

The problem

Machil is part of a pattern of denying justice to victims of atrocities by personnel of the armed forces—despite due process having taken place. The army plays the “veto” card since it enjoys unbridled power and absolute cover in getting away with crimes which, if tried in a civil court, would merit severe punishment.

A classic example is the infamous Pathribal fake encounter in which five officers, including a colonel who later retired as a major general, were found guilty of staging an encounter and killing five civilians in March 2000, following the massacre of 35 Sikhs in Chattisinghpora in South Kashmir. The massacre coincided with President Bill Clinton’s visit to India. The Central Bureau of Investigation had clinching evidence against the officers but in this case the Government of India refused permission to prosecute. The case went up to the Supreme Court, which gave the army the choice of holding a court-martial or being tried in a civil court. The army decided to hold a court of inquiry and disposed of the case!

The power to choose the course of inquiry which has been vested with the army has played a significant role in thwarting justice in such cases. Section 125 of the Army Act, 1950 allows it to choose between a regular criminal court and court-martial. It has continued to shield army personnel.

The section reads as follows: “Section 125. Choice between criminal court and court-martial. When a criminal court and a court-martial have each jurisdiction in respect of an offence, it shall be in the discretion of the officer commanding the army, army corps, division or independent brigade in which the accused person is serving or such other officer as may be prescribed to decide before which court the proceedings shall be instituted, and, if that officer decides that they should be instituted before a court-martial, to direct that the accused person shall be detained in military custody.” Essentially, the personnel can choose the forum, and in most cases they choose the court-martial.

Ironically, erring army personnel choose civil courts when it comes to accidents, as they fear sterner punishment from army courts on grounds of violating discipline. There was, for example, an army major who was dismissed from service with a sentence of seven years by the army court-martial. He later went to civil court. Captain Ravinder Singh Tewatia and Special Police Officer Bharat Bhushan were found guilty of raping two women at their home in Banihal, Doda on February 14, 2000. Two separate charge sheets were filed in the court of the chief judicial magistrate Banihal. Finally, the court-martial confirmed the crime and the captain was punished. He went to the district court but it refused to provide relief, following which he challenged the ruling in the high court. The high court set aside the court-martial judgment but the army appealed before a division bench where the case is pending.

The victims

The biggest hurdle to justice in such cases is that both the Army and Border Security Force Acts are silent about the right to defence of the victims in army courts, an example of which is the Pathribal case. No relative was allowed to present their side. There is absolutely no provision for the victims to plead their case.

There are rare cases like that of Major Rehman Hussain who was dismissed from service on charges of rape in Handwara in 2005. A comprehensive report “Structure of Violence” compiled by the International People’s Tribunal on Human Rights and Justice and Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (released in Sept 2015) points out that:

Military Tribunals compromise the basic principle of equality before the law or equal treatment before the law. While the Pathribal victims wait for justice, we know it is only when court-martials are replaced by an open, transparent and fair trial in a regular independent court system, can the victims of armed forces atrocities in Kashmir even begin to expect justice.

One view has been that the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act gives impunity to army personnel in conflict areas. But in reality, it is the Act and certain sections of the Code of Criminal Procedure along with government orders that give full cover to erring army officers. These laws allow them to go unpunished for violating human rights. Even though the state government fulfilled its job of proving that the three civilians were innocent, the AFT had the last word in labelling them “terrorists” and letting the guilty out of jail.

Accountability laws

Consider these sections of the Code of Criminal Procedure and the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act:

(i) Section 45(1)—Notwithstanding anything contained in Sections 41 to 44 (both inclusive), no member of the armed forces of the union shall be arrested for anything done or purported to be done by him in the discharge of his official duties except after obtaining the consent of the central government.

(ii) Section 197(2)—No court shall take cognisance of any offence alleged to have been committed by any member of the armed forces of the union while acting or purporting to act in the discharge of his official duty, except with the previous sanction of the central government.

(iii) Section 7, Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA)—Protection of persons acting in good faith under this act—No prosecution, suit or other legal proceeding shall be instituted, except with the previous sanction of the central government, against any person in respect of anything done or purported to be done in exercise of the powers conferred by this Act.

It is interesting that so far the AFSPA has not been invoked as there seems to be no need in view of the Army Act covering its interests.

The writer is a senior journalist based in Srinagar (Kashmir) and can be reached at shujaat7867@gmail.com