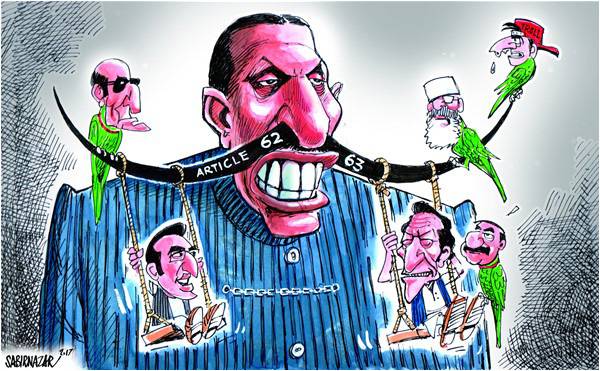

As Pakistan turns 70, political scientists are trying to fathom the dimensions and implications of a new twist in an old paradigm: who rules Pakistan. Until now the prevailing view was that the civil service and military have jointly exercised power directly or indirectly, with the judiciary serving as a handmaiden, while civilian politicians have intermittently been in office. The distinction between “being in power” and “being in office” was central to the paradigm. Now there seems to be a change in the equation, with the judicial-military bureaucracy co-opting power, and the civil service playing the role of the handmaiden (prominently NAB), while civil politicians vainly struggle to remain in a greatly diminished office.

The Movement for the Restoration of Iftikhar Mohammad Chaudhry and his fellow judges of the Supreme Court, culminating in restoration in 2009, had two important consequences. It greatly strengthened the judiciary. But it also politicized it immeasurably. Under Justice Chaudhry, the SC lashed out at a PPP president and two PPP prime ministers. It put the military on the mat for “disappeared” persons in Balochistan and ordered investigations into the financial affairs of the National Logistics Cell run by the military. It pressurized two NAB Chairmen to quit for neglecting to act impartially against ruling politicians. Finally, it broke free from the doctrine of parliamentary supremacy by establishing the doctrine of judicial self-accountability and constitutional supremacy.

After Justice Chaudhry’s departure, the SC has moved to consolidate its political power by two flanking movements. It has signaled its readiness to cooperate rather than conflict with the military establishment. The most obvious case in point is the composition of the Joint Investigation Team led by two powerful military intel agencies. It has decided to target the PMLN prime minister in order to establish its “neutrality” vis a vis both mainstream political parties. It has also decided to take effective control of NAB jointly with the military whose retired officers run it.

The modus operandi of the SC has, however, raised troubling and unprecedented questions in the popular imagination. How did it suddenly come to accept a writ petition by Imran Khan against the Sharifs after the failure of his dharna to overthrow the regime when it had earlier scoffed at it as “rubbish”? Why did it deem it necessary to order the formation of a JIT led by two senior military intel officers when the investigation pertained to money laundering rather than terrorism? Why did it appoint one of the three judges who kicked out the PM to oversee the same premier’s NAB trial in a lower accountability court? Why did it set short time limits for the investigation of the Sharifs in the SC itself and their accountability trial subsequently?

A host of powerful legal questions have also been raised in the five Review Petitions lodged by the ousted prime minister and his family. How the court deals with these will shed further light on its political and legal behavior.

The theory of an imminent “judicial coup” has been doing the rounds for some time. Its proponents have argued that sooner or later the military will nudge the judiciary to center stage because it cannot directly challenge the civil order without openly running afoul of the Constitution. The tipping point probably came when the military was compelled by the force of public opinion and constitutionalism to withdraw its tweet “rejecting” the PM’s notification regarding Dawnleaks. Henceforth, it was decided, a constitutional stick whose legitimacy cannot be questioned should be used to whip the civilians into obeying its “orders”.

If all this is reasonably true, then we can safely predict the turbulence ahead.

Regardless of whether the ousted prime minister’s review petitions are granted relief or not, it is certain that summary NAB proceedings in a lower accountability court will humiliate and then convict the Sharifs and other accused before the scheduled Senate elections next March. The idea is to weaken the ruling Sharif family, and by association, the PMLN so that they cannot threaten the new judicial-military paradigm by winning the Senate elections and making a bid to clip the powers of the SC. Simultaneously, efforts will doubtless be made to try and effect defections from the PMLN so that its ability to mount popular resistance to this “operation” is significantly reduced.

The judiciary’s new role is manifest not just vis a vis PMLN but also PPP. The Sindh High Court has put paid to the Sindh Assembly’s bid to counter NAB with its own accountability mechanism. Ominously enough, a NAB accountability court in Rawalpindi has suddenly woken up to speed up the trail of Asif Ali Zardari in a case of assets without known sources of income.

The Sharifs have realized this impending fate much too late in the day for their own good. But the Zardaris are still posturing with their heads in the sand. The greater tragedy for Pakistan at 70 is that the new “powers-that-be” are as morally and politically bankrupt as the old ones.

The Movement for the Restoration of Iftikhar Mohammad Chaudhry and his fellow judges of the Supreme Court, culminating in restoration in 2009, had two important consequences. It greatly strengthened the judiciary. But it also politicized it immeasurably. Under Justice Chaudhry, the SC lashed out at a PPP president and two PPP prime ministers. It put the military on the mat for “disappeared” persons in Balochistan and ordered investigations into the financial affairs of the National Logistics Cell run by the military. It pressurized two NAB Chairmen to quit for neglecting to act impartially against ruling politicians. Finally, it broke free from the doctrine of parliamentary supremacy by establishing the doctrine of judicial self-accountability and constitutional supremacy.

After Justice Chaudhry’s departure, the SC has moved to consolidate its political power by two flanking movements. It has signaled its readiness to cooperate rather than conflict with the military establishment. The most obvious case in point is the composition of the Joint Investigation Team led by two powerful military intel agencies. It has decided to target the PMLN prime minister in order to establish its “neutrality” vis a vis both mainstream political parties. It has also decided to take effective control of NAB jointly with the military whose retired officers run it.

The modus operandi of the SC has, however, raised troubling and unprecedented questions in the popular imagination. How did it suddenly come to accept a writ petition by Imran Khan against the Sharifs after the failure of his dharna to overthrow the regime when it had earlier scoffed at it as “rubbish”? Why did it deem it necessary to order the formation of a JIT led by two senior military intel officers when the investigation pertained to money laundering rather than terrorism? Why did it appoint one of the three judges who kicked out the PM to oversee the same premier’s NAB trial in a lower accountability court? Why did it set short time limits for the investigation of the Sharifs in the SC itself and their accountability trial subsequently?

A host of powerful legal questions have also been raised in the five Review Petitions lodged by the ousted prime minister and his family. How the court deals with these will shed further light on its political and legal behavior.

The theory of an imminent “judicial coup” has been doing the rounds for some time. Its proponents have argued that sooner or later the military will nudge the judiciary to center stage because it cannot directly challenge the civil order without openly running afoul of the Constitution. The tipping point probably came when the military was compelled by the force of public opinion and constitutionalism to withdraw its tweet “rejecting” the PM’s notification regarding Dawnleaks. Henceforth, it was decided, a constitutional stick whose legitimacy cannot be questioned should be used to whip the civilians into obeying its “orders”.

If all this is reasonably true, then we can safely predict the turbulence ahead.

Regardless of whether the ousted prime minister’s review petitions are granted relief or not, it is certain that summary NAB proceedings in a lower accountability court will humiliate and then convict the Sharifs and other accused before the scheduled Senate elections next March. The idea is to weaken the ruling Sharif family, and by association, the PMLN so that they cannot threaten the new judicial-military paradigm by winning the Senate elections and making a bid to clip the powers of the SC. Simultaneously, efforts will doubtless be made to try and effect defections from the PMLN so that its ability to mount popular resistance to this “operation” is significantly reduced.

The judiciary’s new role is manifest not just vis a vis PMLN but also PPP. The Sindh High Court has put paid to the Sindh Assembly’s bid to counter NAB with its own accountability mechanism. Ominously enough, a NAB accountability court in Rawalpindi has suddenly woken up to speed up the trail of Asif Ali Zardari in a case of assets without known sources of income.

The Sharifs have realized this impending fate much too late in the day for their own good. But the Zardaris are still posturing with their heads in the sand. The greater tragedy for Pakistan at 70 is that the new “powers-that-be” are as morally and politically bankrupt as the old ones.