Ustad Bashir Ahmed (born 1954) is Pakistan’s eminent miniature painter and teacher. He is a critical link between the traditional miniature practice and the teaching of the art in the context of contemporary miniature painting and teaching methodology. Indeed, he symbolises a link between the glorious past and rejuvenated present of South Asian miniature art.

Ustad Bashir Ahmed is an ardent follower of the knowledge and skills imparted to him by his two Ustaads, Haji Mohammad Sharif (1889-1979) and Shaikh Shujaullah (1908-1980). Both taught miniature at the National College of Arts, Lahore. Being taught by the two gave him a great advantage – allowing him to learn directly from the inheritors of two distinct miniature traditions. Upon completion of his studies, Ahmed stayed on at NCA to teach, where he remained a force till his retirement in 2014, having also served as Head of the Fine Arts Department and the Principal.

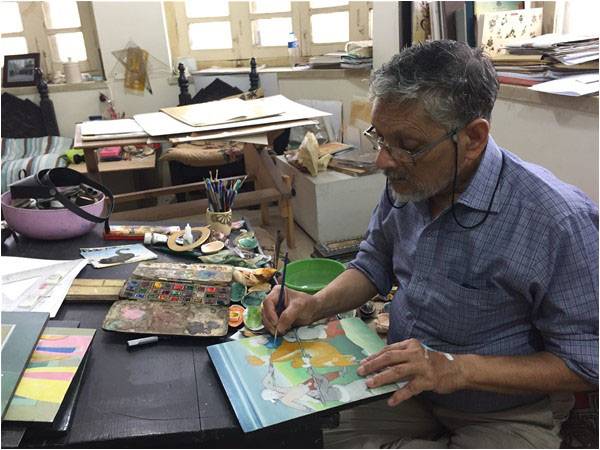

It was difficult for anyone visiting the National College of Arts, Lahore, to miss him – for he was mostly to be found there. Arriving early in the morning for a class assignment, you would see Ustad Bashir Ahmed on campus, doing his morning chores. Or if you were the last to leave, you would see his studio lights dimmed as he worked on a painting. His studio was in the middle of the campus: during the day he would be seen sitting and watching his students or working in the open, preparing paints or wasli paper. In the tradition of a miniature karkhana (workshop), everyone entered his studio bare foot, sat on the floor, and immersed themselves in work with some music being played on a tape recorder. The ambiance in itself contributed to building patience, concentration and immersion in one’s work. In his student days, the Ustad was known for sitting for hours in a single pose, focused on his work. Visiting him recently, after decades, at his studio in Gulberg, Lahore, I found him still sitting in the same pose for hours and his old desk in front of him.

When NCA’s miniature department moved to its new found home, the building vacated by architecture department, Ahmed found a bigger studio with almost two floors. That became his abode and his small group of students also found more space to work.

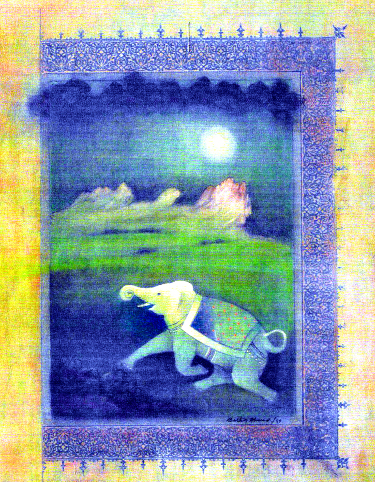

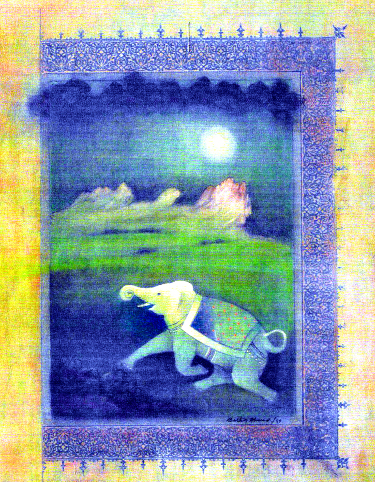

Ustad Bashir Ahmed has done extensive work in classical miniature painting and in different scales. A miniature may not always be as minuscule as the English term conveys. Regardless of the size, the strength of an artist in miniature is challenged for staying loyal to the traditional techniques. He was certainly one of those who stayed put to be the vanguard of traditional practice and rigour, at a time when the vogue was to follow modernism in painting – both in style and subject.

While his critics see him stubbornly adhering to tradition, as the miniature teacher and practitioner, he also started some of the early experimentation in contemporary miniature and passed it on to his talented student body. Pakistan’s famous visual artist Aisha Khalid, a leading figure in taking forward the contemporary miniature in newer directions, always recognises the key role of Ustad Bashir Ahmed in her training. She recalls some of the innovative assignments given by him to inspiring students to think beyond the usual. Once Ustad Bashir himself, spending hours, made miniature models and asked students to paint the minuscule spaces – allowing them to have a better sense of three-dimensional space and objects at smaller scale and how to use them in compositions instead of copying from photos of classical miniature paintings. Aisha Khalid also remembers when Ustad Ahmed experimented with tea staining of wasli, a technique taken forward by Imran Qureshi and others.

Ustad Bashir Ahmed also ventured into printmaking, metal painting, sculpture and landscape, showing his creativity and inventiveness. But he remained close to his miniature roots. He learnt the art of miniature restoration from his two ustads.

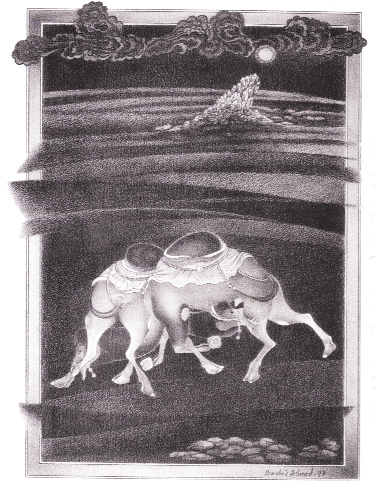

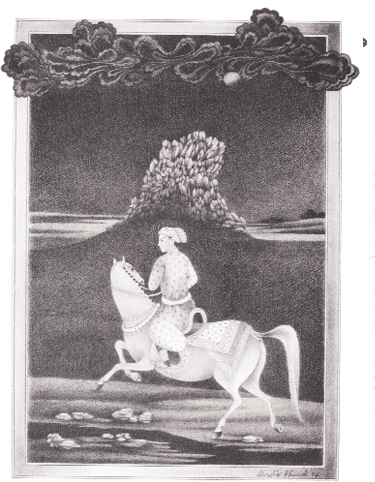

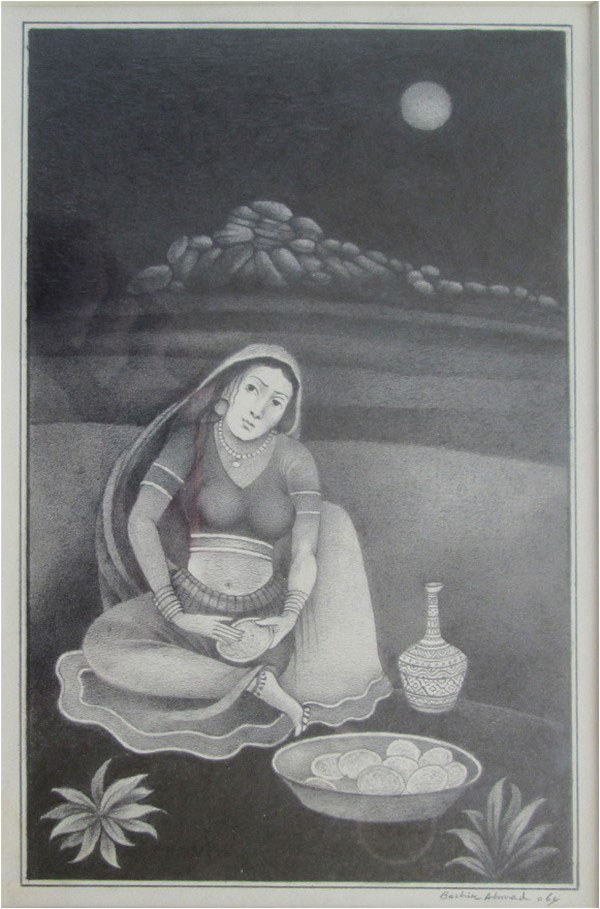

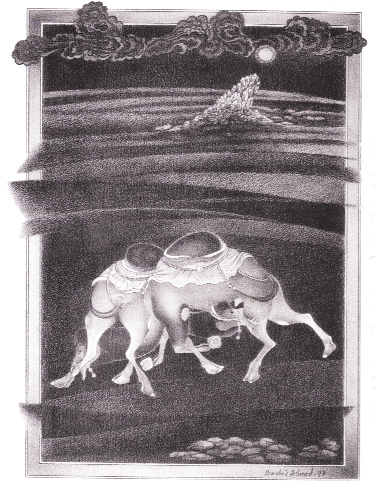

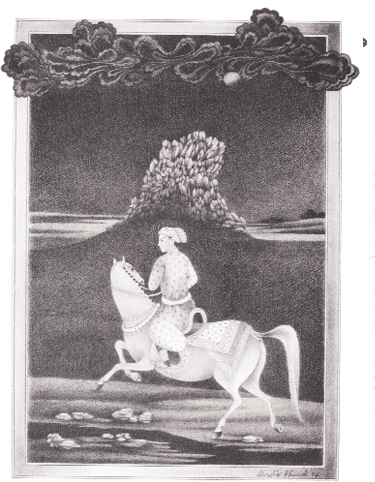

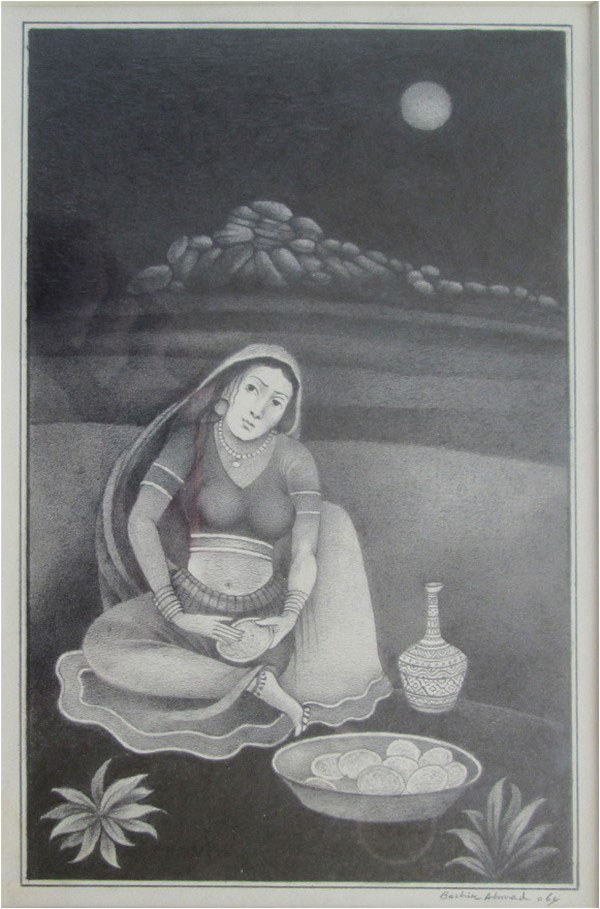

His distinctive work in graphite is my favorite. The monochrome graphite shows his masterful drawing, command of tonal variation and control over the medium. It shows how he creates spacial depth and presence of characters in shades of black, and that too, from a simple medium – graphite.

His work in graphite is Ahmad’s successful experimentation with traditional miniature. It required the vision of a miniaturist of his stature. Interestingly none of his students have taken forward such work in graphite to the next level. It may be because of the quantum of work required. Some of them even eschew graphite for its limited potential or for it being distinct from the common idea of a painting, which has to have layers of colors. But when one looks at Ahmad’s graphites – camels fighting, a princess in waiting or a Mongolian figure contemplating in moon light – it is difficult not to sail through the twists and turns of his graphite strokes and to establish a dialogue with those strong characters that emerge out of the black hues. The Ustad particularly mentions the time required for graphite work, especially the challenges in creating chiaroscuro.

For Ustad Bashir Ahmad, the process matters as much as the final product. He has remained loyal to the rigour required for the discipline. Shahzia Sikander, the famed Pakistani artist, was Ustad Ahmed’s first student to break the barriers of tradition, successfully experimenting with it and achieving an international presence. She ecstatically recalls the choice and treatment of Ustad Ahmed’s colours. In her view, no one has been able to exceed Ustad Ahmed’s ability to transform colours in miniature painting.

And for Ustad Ahmed, a student of miniature should cover every step in learning the practice – from making one’s own paints, paintbrush and wasli paper to the art of miniature painting itself. As a teacher he created a generation of painters trained in the highest level of practice and committed to take it forward. Aisha Khalid mentioned how in hindsight she felt thankful for the rigours of Ustad Bashir Ahmad’s studio - a complete Ustad’s riaazat where she learnt from “colour-making to brush strokes”.

Ustad Ahmed even taught support staff to make Wasli and traditional paints and brushes, thus also conserving some of the traditional techniques. Most of the painters, even those now based overseas, still contact the trained staff to get the wasli, traditional paints or brushes.

The list of his students who have taken contemporary miniature in Pakistan to a newer level and received international acclaim includes Shahzia Sikander, Imran Qureshi, Aisha Khalid, Nusra Latif, Talha Rathor, Fasih Ahmed, Tazen Qayyum, Sumaira Tazeen, Waseem Ahmed, Usman Saeed, Irfan Hasan – and the list goes on.

Shahzia Sikander still recalls endless days spent listening to Iqbal’s Shikwa and Ustad Ahmed explaining to students the magnum opus while she worked on her defining thesis “The Scroll” in 1990. Sikander says he was “a very generous teacher because his notion of time and knowledge was unbound. He was always available to give information and inspiration while being rigorous.”

Given his vital role in teaching miniature and reviving it, his contribution is not as widely recognized and that may have been because of his strict style of teaching, at times hinging on obstinacy. He wants submission to the tradition of centuries-old Ustads – something not possible in the 1990’s and certainly very difficult in today’s world. He himself, however, remains devout to his ustads: the deep respect with which he narrates his time as an apprentice with Haji Sharif and Shaikh Shujaullah is always evident. As a mark of respect and probably a good luck charm, the paint-boxes given to him by his Ustads are still part of the pile on his desk and he feels proud to habe not only passed on the strict discipline to a large number of students but also to have saved wasli and paint-making techniques. Regardless of the level of recognition, his students always mention his role and the training that equipped them with the tools to do their work whether in contemporary painting, print-making, textiles or animation. Reflecting on his works and contribution Ustad Bashir Ahmed cited Majroh Sultanpuri’s verse, which the latter recited to him on seeing his work when the two met in Lahore:

Mere hi sang-o khisht say tameer e bam o dar

Aur Mere hi ghar ko sheher may shamyl kaha na jaay

[The city was constructed from my building blocks

Yet my abode was never considered to be a part of the city]

Recalling the dimmed lights of his college studio, I was about to leave him at his new studio after our long meeting, one that ended at dusk. But this time, he said that he was also homebound, but with no means of transportation of his own. One of his trained wasli-makers present in the studio offered to drop him and the Ustad vanished on the backseat of a motorcycle into the Lahori night.

Ustad Bashir Ahmed will remain an enigma.

The writer can be reached at smt2104@caa.columbia.edu

Ustad Bashir Ahmed is an ardent follower of the knowledge and skills imparted to him by his two Ustaads, Haji Mohammad Sharif (1889-1979) and Shaikh Shujaullah (1908-1980). Both taught miniature at the National College of Arts, Lahore. Being taught by the two gave him a great advantage – allowing him to learn directly from the inheritors of two distinct miniature traditions. Upon completion of his studies, Ahmed stayed on at NCA to teach, where he remained a force till his retirement in 2014, having also served as Head of the Fine Arts Department and the Principal.

For Ustad Bashir Ahmad, the process matters as much as the final product

It was difficult for anyone visiting the National College of Arts, Lahore, to miss him – for he was mostly to be found there. Arriving early in the morning for a class assignment, you would see Ustad Bashir Ahmed on campus, doing his morning chores. Or if you were the last to leave, you would see his studio lights dimmed as he worked on a painting. His studio was in the middle of the campus: during the day he would be seen sitting and watching his students or working in the open, preparing paints or wasli paper. In the tradition of a miniature karkhana (workshop), everyone entered his studio bare foot, sat on the floor, and immersed themselves in work with some music being played on a tape recorder. The ambiance in itself contributed to building patience, concentration and immersion in one’s work. In his student days, the Ustad was known for sitting for hours in a single pose, focused on his work. Visiting him recently, after decades, at his studio in Gulberg, Lahore, I found him still sitting in the same pose for hours and his old desk in front of him.

When NCA’s miniature department moved to its new found home, the building vacated by architecture department, Ahmed found a bigger studio with almost two floors. That became his abode and his small group of students also found more space to work.

He wants submission to the tradition of centuries-old Ustads - something not possible in the 1990's and certainly very difficult in today's world

Ustad Bashir Ahmed has done extensive work in classical miniature painting and in different scales. A miniature may not always be as minuscule as the English term conveys. Regardless of the size, the strength of an artist in miniature is challenged for staying loyal to the traditional techniques. He was certainly one of those who stayed put to be the vanguard of traditional practice and rigour, at a time when the vogue was to follow modernism in painting – both in style and subject.

While his critics see him stubbornly adhering to tradition, as the miniature teacher and practitioner, he also started some of the early experimentation in contemporary miniature and passed it on to his talented student body. Pakistan’s famous visual artist Aisha Khalid, a leading figure in taking forward the contemporary miniature in newer directions, always recognises the key role of Ustad Bashir Ahmed in her training. She recalls some of the innovative assignments given by him to inspiring students to think beyond the usual. Once Ustad Bashir himself, spending hours, made miniature models and asked students to paint the minuscule spaces – allowing them to have a better sense of three-dimensional space and objects at smaller scale and how to use them in compositions instead of copying from photos of classical miniature paintings. Aisha Khalid also remembers when Ustad Ahmed experimented with tea staining of wasli, a technique taken forward by Imran Qureshi and others.

Ustad Bashir Ahmed also ventured into printmaking, metal painting, sculpture and landscape, showing his creativity and inventiveness. But he remained close to his miniature roots. He learnt the art of miniature restoration from his two ustads.

His distinctive work in graphite is my favorite. The monochrome graphite shows his masterful drawing, command of tonal variation and control over the medium. It shows how he creates spacial depth and presence of characters in shades of black, and that too, from a simple medium – graphite.

His work in graphite is Ahmad’s successful experimentation with traditional miniature. It required the vision of a miniaturist of his stature. Interestingly none of his students have taken forward such work in graphite to the next level. It may be because of the quantum of work required. Some of them even eschew graphite for its limited potential or for it being distinct from the common idea of a painting, which has to have layers of colors. But when one looks at Ahmad’s graphites – camels fighting, a princess in waiting or a Mongolian figure contemplating in moon light – it is difficult not to sail through the twists and turns of his graphite strokes and to establish a dialogue with those strong characters that emerge out of the black hues. The Ustad particularly mentions the time required for graphite work, especially the challenges in creating chiaroscuro.

For Ustad Bashir Ahmad, the process matters as much as the final product. He has remained loyal to the rigour required for the discipline. Shahzia Sikander, the famed Pakistani artist, was Ustad Ahmed’s first student to break the barriers of tradition, successfully experimenting with it and achieving an international presence. She ecstatically recalls the choice and treatment of Ustad Ahmed’s colours. In her view, no one has been able to exceed Ustad Ahmed’s ability to transform colours in miniature painting.

And for Ustad Ahmed, a student of miniature should cover every step in learning the practice – from making one’s own paints, paintbrush and wasli paper to the art of miniature painting itself. As a teacher he created a generation of painters trained in the highest level of practice and committed to take it forward. Aisha Khalid mentioned how in hindsight she felt thankful for the rigours of Ustad Bashir Ahmad’s studio - a complete Ustad’s riaazat where she learnt from “colour-making to brush strokes”.

Ustad Ahmed even taught support staff to make Wasli and traditional paints and brushes, thus also conserving some of the traditional techniques. Most of the painters, even those now based overseas, still contact the trained staff to get the wasli, traditional paints or brushes.

The list of his students who have taken contemporary miniature in Pakistan to a newer level and received international acclaim includes Shahzia Sikander, Imran Qureshi, Aisha Khalid, Nusra Latif, Talha Rathor, Fasih Ahmed, Tazen Qayyum, Sumaira Tazeen, Waseem Ahmed, Usman Saeed, Irfan Hasan – and the list goes on.

Shahzia Sikander still recalls endless days spent listening to Iqbal’s Shikwa and Ustad Ahmed explaining to students the magnum opus while she worked on her defining thesis “The Scroll” in 1990. Sikander says he was “a very generous teacher because his notion of time and knowledge was unbound. He was always available to give information and inspiration while being rigorous.”

Given his vital role in teaching miniature and reviving it, his contribution is not as widely recognized and that may have been because of his strict style of teaching, at times hinging on obstinacy. He wants submission to the tradition of centuries-old Ustads – something not possible in the 1990’s and certainly very difficult in today’s world. He himself, however, remains devout to his ustads: the deep respect with which he narrates his time as an apprentice with Haji Sharif and Shaikh Shujaullah is always evident. As a mark of respect and probably a good luck charm, the paint-boxes given to him by his Ustads are still part of the pile on his desk and he feels proud to habe not only passed on the strict discipline to a large number of students but also to have saved wasli and paint-making techniques. Regardless of the level of recognition, his students always mention his role and the training that equipped them with the tools to do their work whether in contemporary painting, print-making, textiles or animation. Reflecting on his works and contribution Ustad Bashir Ahmed cited Majroh Sultanpuri’s verse, which the latter recited to him on seeing his work when the two met in Lahore:

Mere hi sang-o khisht say tameer e bam o dar

Aur Mere hi ghar ko sheher may shamyl kaha na jaay

[The city was constructed from my building blocks

Yet my abode was never considered to be a part of the city]

Recalling the dimmed lights of his college studio, I was about to leave him at his new studio after our long meeting, one that ended at dusk. But this time, he said that he was also homebound, but with no means of transportation of his own. One of his trained wasli-makers present in the studio offered to drop him and the Ustad vanished on the backseat of a motorcycle into the Lahori night.

Ustad Bashir Ahmed will remain an enigma.

The writer can be reached at smt2104@caa.columbia.edu