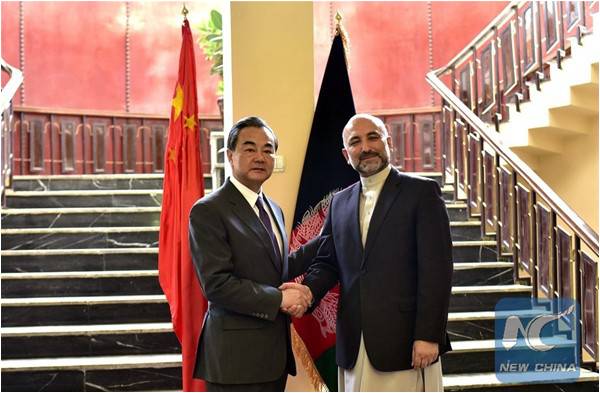

In late June, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi visited Afghanistan and Pakistan in an attempt to mediate between the two neighbours. Wang Yi’s shuttle diplomacy is marked as the first-ever attempt by China to ease differences between the two countries. Officials had exchanged harsh words after a terrorist attack in Kabul. The Chinese stepped in to end the recrimination.

While it is too early to forecast any aspects of a mediation offer, it would be interesting to note how Pakistan and China relations evolve in the context of Pakistan’s existing policies on Afghanistan.

For now, for the Pakistani side, it is all very well that the Chinese come in and mediate. China, is, after all, Pakistan’s trusted, all-weather strategic partner, and their relations are often lyrically lauded. Whatever China comes to conclude on Afghan affairs will be palatable to many in Pakistan.

Strikingly, some even go to the extent of saying that China’s approach towards Afghanistan accommodates the Pakistani position, and continues to do so. They cite that much of what Wang Yi stated in the joint press release sounded like an endorsement of Pakistan’s stance. For one, it calls for creating an “enabling environment” for the Afghan Taliban to join the negotiation process, which is somewhat a Pakistani position. To put things in context, Afghanistan urges both talk and fight simultaneously; Pakistan responds that the two cannot take place at the same time. (To be sure, Pakistan has repeatedly condemned terrorism in Afghanistan, but calls for resolving the issue through an Afghan-owned peace process.)

While this view of China-Pakistan bonhomie on Afghanistan may be true in the past and present context, one should be realistic about what the future may hold. What if the enabling environment is futile?

The hopes Afghans have of China should not be discounted either. One would argue that China’s mediation offer is no less than the outcome of an effort put in by Afghan President Ashraf Ghani. It was he who, after assuming power in 2014, made his first foreign visit to Beijing, persuading the Chinese leadership to ask Pakistan to bring the Afghan Taliban to the negotiation table. And bring they did: the Quadrilateral Coordination Group (QCG), comprising China, Pakistan, the United States, and Afghanistan, was formed and met the Afghan Taliban more than once after they held off meetings.

The QCG was a diplomatic way forward in its own right. And now comes the mediation offer from China. In Afghanistan, the news of the offer was announced by no less than the President’s Office, saying it would be the “first time that China wants to be a mediator in Afghanistan’s peace process.”

More important is to take into account China’s own calculation. Arguably, China’s latitude to explore the option of talks with the Taliban may partly be to contest their (Taliban’s) main militant adversary, the Islamic State. ISIS’s Khurasan chapter, encompassing Pakistan and Afghanistan, is trying to gather different brands of militants under one umbrella. These men even include anti-China militants, who are clearly more of a direct threat. What if that threat were neutralized?

No one can deny that China has scaled up its role in the region. Throughout the American years in Afghanistan, China was a bystander, watching from the sidelines. Americans thought China was freeriding. Two years ago, it became one of the four members of the QCG alongside the US, willing to hold peace talks with the Taliban. And today, it is taking steps forward to mediate between the two neighbours without even needing the US. As China’s interest in Afghanistan grows, for economic or political reasons, so too will it have to look at that country from its own lens, which may or may not click with Pakistan’s position.

More than the future of the Taliban, the future of Afghan power politics may directly impact China. Pakistan has traditionally found partners in Pashtun elements in Afghanistan, apparently for physical and linguistic convenience. But it is the territory of the non-Pashtun elements, in the north, close to China, which the Chinese would not want to be slip into a void. It is in these areas where the political forces opposed to the Taliban’s government reside. Some of these forces are even in the government now, with a deeply skeptical view of the outcome of the entire reconciliation process. Pakistan would be better off exploring sympathizers beyond a segment in one single ethnic group.

What seems particularly unique about China’s expectations is more regional connectivity. The first point of the joint statement, released by the three countries, ensures their commitment to “enhancing regional connectivity and economic cooperation”.

In Pakistan, the entire idea of “regional connectivity” is centred on the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Some Pakistani officials have offered other countries to join, to make it a winnable option for all. But limiting regional connectivity with CPEC misses the point. As of now, on the Afghanistan front, every terrorist attack or border clash on the western front is responded to with a closure of the border, which halts the supply of goods to Afghanistan. The spirit of regional connectivity goes missing then.

As per the joint statement, the three countries agree to “establish the China-Afghanistan-Pakistan Foreign Ministers’ dialogue mechanism to cooperate on issues of mutual interest, beginning with economic cooperation.” Overall, the point of regional connectivity is thrust forward repeatedly by the Chinese, more so perhaps because it is the least controversial topic. With the involvement of foreign ministers, Pakistan will have to prove the point is well-taken.

While it is too early to forecast any aspects of a mediation offer, it would be interesting to note how Pakistan and China relations evolve in the context of Pakistan’s existing policies on Afghanistan.

For now, for the Pakistani side, it is all very well that the Chinese come in and mediate. China, is, after all, Pakistan’s trusted, all-weather strategic partner, and their relations are often lyrically lauded. Whatever China comes to conclude on Afghan affairs will be palatable to many in Pakistan.

Strikingly, some even go to the extent of saying that China’s approach towards Afghanistan accommodates the Pakistani position, and continues to do so. They cite that much of what Wang Yi stated in the joint press release sounded like an endorsement of Pakistan’s stance. For one, it calls for creating an “enabling environment” for the Afghan Taliban to join the negotiation process, which is somewhat a Pakistani position. To put things in context, Afghanistan urges both talk and fight simultaneously; Pakistan responds that the two cannot take place at the same time. (To be sure, Pakistan has repeatedly condemned terrorism in Afghanistan, but calls for resolving the issue through an Afghan-owned peace process.)

Pakistan has traditionally found partners in Pashtun elements in Afghanistan, apparently for physical and linguistic convenience. But it is the territory of the non-Pashtun elements, in the north, close to China, which the Chinese would not want to be slip into void

While this view of China-Pakistan bonhomie on Afghanistan may be true in the past and present context, one should be realistic about what the future may hold. What if the enabling environment is futile?

The hopes Afghans have of China should not be discounted either. One would argue that China’s mediation offer is no less than the outcome of an effort put in by Afghan President Ashraf Ghani. It was he who, after assuming power in 2014, made his first foreign visit to Beijing, persuading the Chinese leadership to ask Pakistan to bring the Afghan Taliban to the negotiation table. And bring they did: the Quadrilateral Coordination Group (QCG), comprising China, Pakistan, the United States, and Afghanistan, was formed and met the Afghan Taliban more than once after they held off meetings.

The QCG was a diplomatic way forward in its own right. And now comes the mediation offer from China. In Afghanistan, the news of the offer was announced by no less than the President’s Office, saying it would be the “first time that China wants to be a mediator in Afghanistan’s peace process.”

More important is to take into account China’s own calculation. Arguably, China’s latitude to explore the option of talks with the Taliban may partly be to contest their (Taliban’s) main militant adversary, the Islamic State. ISIS’s Khurasan chapter, encompassing Pakistan and Afghanistan, is trying to gather different brands of militants under one umbrella. These men even include anti-China militants, who are clearly more of a direct threat. What if that threat were neutralized?

No one can deny that China has scaled up its role in the region. Throughout the American years in Afghanistan, China was a bystander, watching from the sidelines. Americans thought China was freeriding. Two years ago, it became one of the four members of the QCG alongside the US, willing to hold peace talks with the Taliban. And today, it is taking steps forward to mediate between the two neighbours without even needing the US. As China’s interest in Afghanistan grows, for economic or political reasons, so too will it have to look at that country from its own lens, which may or may not click with Pakistan’s position.

More than the future of the Taliban, the future of Afghan power politics may directly impact China. Pakistan has traditionally found partners in Pashtun elements in Afghanistan, apparently for physical and linguistic convenience. But it is the territory of the non-Pashtun elements, in the north, close to China, which the Chinese would not want to be slip into a void. It is in these areas where the political forces opposed to the Taliban’s government reside. Some of these forces are even in the government now, with a deeply skeptical view of the outcome of the entire reconciliation process. Pakistan would be better off exploring sympathizers beyond a segment in one single ethnic group.

What seems particularly unique about China’s expectations is more regional connectivity. The first point of the joint statement, released by the three countries, ensures their commitment to “enhancing regional connectivity and economic cooperation”.

In Pakistan, the entire idea of “regional connectivity” is centred on the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Some Pakistani officials have offered other countries to join, to make it a winnable option for all. But limiting regional connectivity with CPEC misses the point. As of now, on the Afghanistan front, every terrorist attack or border clash on the western front is responded to with a closure of the border, which halts the supply of goods to Afghanistan. The spirit of regional connectivity goes missing then.

As per the joint statement, the three countries agree to “establish the China-Afghanistan-Pakistan Foreign Ministers’ dialogue mechanism to cooperate on issues of mutual interest, beginning with economic cooperation.” Overall, the point of regional connectivity is thrust forward repeatedly by the Chinese, more so perhaps because it is the least controversial topic. With the involvement of foreign ministers, Pakistan will have to prove the point is well-taken.