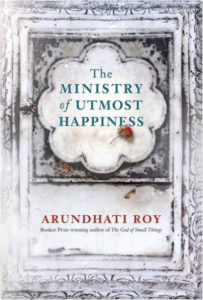

If you do not have an opinion on Arundhati Roy’s new book yet then you have little reason to be alive. You should be prepared to be shunned by the social media literati who love to see books (yes, only in Pakistan do I meet people who say “Oh I have seen your book” as opposed to “have read it”). You must brace yourself for the virtual cold shoulder by those eagerly discussing blurbs of the reviews of her new work as they appear on their Facebook and Twitter feeds, even if they have no intention of ever reading the book itself. So speak now or hold your peace forever.

If you do not have an opinion on Arundhati Roy’s new book yet then you have little reason to be alive. You should be prepared to be shunned by the social media literati who love to see books (yes, only in Pakistan do I meet people who say “Oh I have seen your book” as opposed to “have read it”). You must brace yourself for the virtual cold shoulder by those eagerly discussing blurbs of the reviews of her new work as they appear on their Facebook and Twitter feeds, even if they have no intention of ever reading the book itself. So speak now or hold your peace forever.Now that you have been warned, let me tell you that you don’t even have to comment on her art. You can just rant on her clothes, her hair, her age or the lack of ageing – even her choice of lifestyle is up for discussion. For when it comes to writers who happen to be women, somehow we can’t seem to separate their talent from their looks. The best of the papers are doing that.

It bothered me greatly that The Guardian’s review of her latest started with how “Roy is swathed in pale pink linen, draped around her upper body like a sari over rolled up jeans, open-toed sandals and bright red nail varnish; she moves with arresting grace, and speaks softly. At 55, she retains an impish air of ingénue about her, and the quiet mischief in her smile suggests a certain pleasure in her own troublesome single-mindedness...” I don’t ever recall reading a review of a man writer starting out with how the clothes were draped across his body and how at 60 he could still hobble and how his smile suggested his own stubbornness to keep breathing…!

There seems to be a duplicity here with what’s sauce for the goose is not sauce for gander or even a starter. Earlier in the same paper, Andrew Anthony began by describing Roy as, “Small, delicately boned, a beguiling mixture of piercing dark eyes and bright easy smile, she is a warm presence… the grey tint to her curls lends depth to a still strikingly youthful face.” He devoted a couple of paras to her appearance, before neatly tying up her looks with her talent in a tidy little package by adding, “The shrill prose is hard to reconcile with the softly spoken middle-aged woman sitting opposite me.”

Since when does how we look have anything to do with how we write? I have yet to read a review of a man author’s work that discusses his appearance in relation to his talent. Imagine how strange it would sound if a critic wrote about Arvind Adiga’s hair (or the lack of it) or Mohammed Hanif’s height or Omar Shahid’s weight?

Yet when it is a woman’s writing being discussed, that space seems to be open to all, allowing critics to somehow relate a woman’s looks and mannerisms with her creativity. It almost makes you wonder whether writers like E.L James of Fifty Shades of Grey fame or J.K Rowling, who dared to do something unconventional chose to use their initials, when they first started out.

When it comes to writers who happen to be women, somehow we can't seem to separate their talent from their looks

This fear of having one’s character and creativity mansplained by one’s appearance is not new to women writers. Back in the 1930’s when the Angaray anthology came out, Rashid Jahan was termed the bad girl of literature and her short hair used as proof that she was a bad influence on young girls. Ismat Chugtai was termed too unfeminine and her writings deemed too manly. But what is fascinating is that after so many years, women who write are still attacked or admired for their appearance: their looks almost overshadowing their credibility as artists.

And it is not just Roy who is subjected to this. This practice is rampant all over, almost expected, infact. In a piece in Scroll, novelist Shazaf Haider wrote about the uncomfortable experience of people’s obsession with her looks overshadowing her talent as a writer when her novel first came out. She writes, “This was the not so funny part of being published, this insidious attempt to appropriate my body through my writing.” This silencing of a woman’s talent by equating it in direct proportion to her looks can create lasting biases that we internalise, leading to self-doubt and self- censorship. As if there wasn’t enough of that around already.

I myself have gone through this when my book Nobody Killed Her first came out. At a local bookstore my 6-year-old daughter got very excited and started jumping up and down pointing,‘that’s my mum’s book’. The bookseller took a look at the novel, then at me. He then proceeded to look at the author photo at the back jacket, making no attempt to hide his doubt. I told him it really was me, to which he chuckled and replied that I did not look like a writer. How exactly does a writer look? I wondered. To this he looked at my frenzied state holding the hands of my two children while balancing groceries on my hip and decided not to answer.

In that moment he planted a seed of self-doubt in me where I actually felt myself questioning the authorship of my own book. I felt small and undeserving and in short, ready to give up the credit that I deserved. And this is what judging women by their looks does. Perhaps we are not conscious of this but it’s a lasting damage that affects the way we evaluate talent, especially our own.

As novelist Meena Kandasamy said in a recent interview, “The death of a woman as a writer is something that takes place constantly and in ways besides censorship as well.”

It's bad enough in showbiz where you have a fifty-year-old Shahrukh Khan romancing a sixteen-year-old waif while his female co-star of only ten years ago now has to play his mother

We have enough limitations on us without being burdened by the weight of appearances as well. It’s bad enough in showbiz where you have a fifty-year-old Shahrukh Khan romancing a sixteen-year-old waif while his female co-star of only ten years ago now has to play his mother. We don’t need this in publishing too.

Unlike in cinema where age seems to dictate what women can or cannot play, looks in literature should not dictate our talent. Writer Anam Zakariya has often been told that she looks too young to be writing about Partition, others are deemed too pretty to be writing about serious topics like violence against women or too homely to be writing about politics or too ugly to be marketed as romance novelists and their author photo banished to the far corner of their book jackets. It’s bad enough that women often cannot tell their stories for fear of what society would think – they don’t need this added pressure of appearance as well. I can’t imagine a man author dressing up for an interview or book review so why should a woman author be expected to? Why must our achievements be hijacked by our looks or the lack of it, anyway? Why can’t a review of Roy’s new book be about the book, just as Arvind Adiga’s can be?

As Suchitra Vijyan points out in Daily O, “Would anyone review a book by Salman Rushdie by saying how the shirt fabric caresses Salman Rushdie’s belly?” I doubt it. And it’s about time we started doing the same by taking the gender out of writing. Writing should be judged on its quality, not by the sex or ‘sexiness’ of its author.

Dr. Sabyn Javeri is an Assistant Professor at the Arzu center for Literature and Languages at Habib University. She has a Masters from Oxford University and a doctorate from the University of Leicester. She is an award-winning short story writer and the author of bestselling novel ‘Nobody Killed Her’