China’s status as the world’s most populous nation has been touted ad nauseum, and is probably old news for the average primary school graduate. What is less well known is that the country has historically faced tremendous pressure in cultivation capacity, and was food insecure for much of its history. China houses 22 percent of the world’s population but has only 7 percent of the world’s arable land. Technological innovation since the 1960s has ensured that the country is self-sufficient in the production of grain most years, but there have been occasions when it has had to import even its staple grain, rice.

Over the last decade, the stress on food production has increased, as China faces alarming environmental crises, including a significant depletion in its aquifers. Rapid industrialization also means that the Chinese are abandoning the agriculture sector in droves, and most farmers are now over 50 years old.

In addition, China’s philosophy on self-sufficiency is changing as the country embraces an increasingly capitalist model of production. In the decades after the Communist takeover, self-sufficiency in foodgrains was not only emphasized, but enforced. This is now giving way to new thinking wherein Chinese policymakers are evaluating the benefits of importing land-intensive, relatively low value crops like staple grains, and thus releasing China’s scarce agricultural land for the production of high-value crops.

This shift is likely to become more popular as the incidence of poverty continues to decrease in the country, and the middle class increases in size and influence. As consumers become more affluent, the demand for more exotic foods begins to increase. Meat consumption per person trebled in China over a period of about twenty years from the mid-1980s onwards. Foods that had hardly featured in traditional Chinese dishes, such as avocadoes, berries, aged cheese and chocolate are now heavily in demand at least in the urban centers.

As things stand now, China is the world’s biggest producer of agricultural products, but also the world’s biggest importer in this category. But old habits die hard, and the instinct to have the country’s food needs met through its own resources is very much apparent. After all, the Community Party came to power in China in times of extreme famine, and collectivization of agriculture, to achieve self-sufficiency in grain production, was the cornerstone of its governance philosophy.

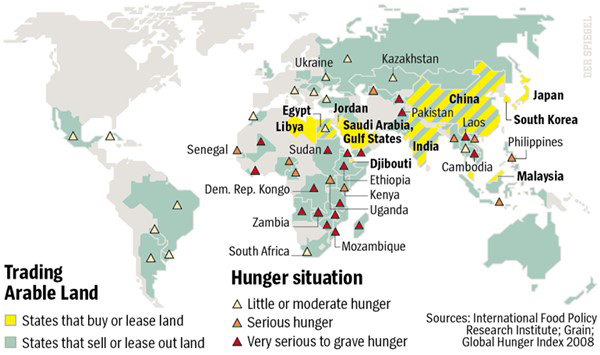

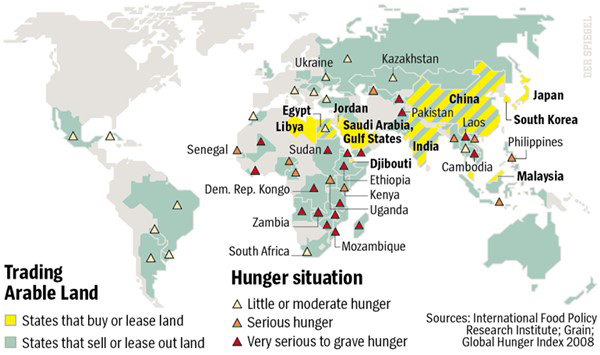

This is why China is leading the way into what is becoming known as “overseas farming”—investing in land in developing countries, and providing technical and research support to farm the land, with the aim of supplying its domestic market. So this is not about imports, but actually about its own farms overseas or beyond its borders. The first step involved the acquisition of land for rice cultivation in Laos and Cambodia in the early 2000s. But now Chinese farms are to be found as far afield as Argentina (which now supplies a significant proportion of China’s meat needs, through Chinese-owned farms), and all across Africa. Lately, there is a greater emphasis on investing closer to home. A few years ago, before war broke out in the Ukraine, it was being reported that China was going to lease no less than 3 million hectares in that country as farmland for grain cultivation and livestock rearing, particularly pig farming. Russia has also been approached to consider leasing land in its eastern provinces which border China.

These trends have been contentious in almost all the countries where they have taken place. Taking over land in another country is always an evocative issue, particularly when it involves involuntary repatriation. Land grabs are seen as the first step in colonization, and the history of colonization in much of the developing world has ensured that such initiatives are laden with symbolism. Nevertheless, China has encountered little resistance in its move to buy or lease farmland all over the world—not least because its overtures come with some tempting freebies, mainly heavy investment in agricultural research, and the demonstration of technological innovation. In many countries, the acquisition of farmland by foreigners is illegal. But in those cases, China either uses the modality of long-term leases, or financing infrastructure development and some inputs, in return for favorable prices for the produce.

The manpower employed also varies. In Africa, farm managers may be Chinese, but the labor is all local. In Russia, on the other hand, China is in negotiations to lease what is currently abandoned land, and in fact shift people across the border to cultivate it, given that the areas in question are hardly populated.

In short, the Chinese are nothing if not flexible—they need to ensure that their people are fed, and they will do what they can to make sure that happens. For a country like Pakistan, with its history of policy inconsistency and flip flops on key decisions, this sort of single-minded determination is almost impossible to fathom.

Given this recent history, the apparent fact that China wants to invest in agriculture in Pakistan should not have been such a big revelation. The daily Dawn recently published what appears to be China’s version of the Long Term Plan for the China Pakistan Economic Corridor investments in Pakistan, and there was much hue and cry over the fact that agriculture features prominently in the Plan.

As featured in Dawn, the Plan apparently lays out a pretty standard strategy typical of China for agriculture. The investment planned will go all the way through the supply chain, as it does in Africa, with China investing in provision of inputs, operating its own farms, and processing agricultural goods for export. A big gap in the Pakistani supply chain, i.e. the provision of warehousing and storage, has been recognized as a bottleneck and will be addressed. Control of the enterprises will rest with the Chinese, as it does in East Asia and Africa, and the initiatives will be financed largely by Chinese banks, lending to their own conglomerates.

There is no denying that Pakistan’s agriculture sector is in crisis, and needs a heavy dose of investment. At the same time, the sudden corporatization of a highly labour intensive sector, which is serviced by the most vulnerable segments of our population, can have devastating socioeconomic consequences. If anything, the Chinese should be sympathetic, having built a revolution on the back of peasant farmers. But we need to tread very carefully here.

Firstly, the government should make the details of the plans public, and be very clear about the safeguard policies that will be implemented. One cannot expect a foreign country to prioritize the interests of one’s vulnerable population. That is for our government and our society to do. Sadly, Pakistan has scant tradition of taking care of its marginalized groups. Let’s hope we do better in the future.

The writer is an independent researcher based in Islamabad.

Over the last decade, the stress on food production has increased, as China faces alarming environmental crises, including a significant depletion in its aquifers. Rapid industrialization also means that the Chinese are abandoning the agriculture sector in droves, and most farmers are now over 50 years old.

In addition, China’s philosophy on self-sufficiency is changing as the country embraces an increasingly capitalist model of production. In the decades after the Communist takeover, self-sufficiency in foodgrains was not only emphasized, but enforced. This is now giving way to new thinking wherein Chinese policymakers are evaluating the benefits of importing land-intensive, relatively low value crops like staple grains, and thus releasing China’s scarce agricultural land for the production of high-value crops.

This shift is likely to become more popular as the incidence of poverty continues to decrease in the country, and the middle class increases in size and influence. As consumers become more affluent, the demand for more exotic foods begins to increase. Meat consumption per person trebled in China over a period of about twenty years from the mid-1980s onwards. Foods that had hardly featured in traditional Chinese dishes, such as avocadoes, berries, aged cheese and chocolate are now heavily in demand at least in the urban centers.

As things stand now, China is the world’s biggest producer of agricultural products, but also the world’s biggest importer in this category. But old habits die hard, and the instinct to have the country’s food needs met through its own resources is very much apparent. After all, the Community Party came to power in China in times of extreme famine, and collectivization of agriculture, to achieve self-sufficiency in grain production, was the cornerstone of its governance philosophy.

This is why China is leading the way into what is becoming known as “overseas farming”—investing in land in developing countries, and providing technical and research support to farm the land, with the aim of supplying its domestic market. So this is not about imports, but actually about its own farms overseas or beyond its borders. The first step involved the acquisition of land for rice cultivation in Laos and Cambodia in the early 2000s. But now Chinese farms are to be found as far afield as Argentina (which now supplies a significant proportion of China’s meat needs, through Chinese-owned farms), and all across Africa. Lately, there is a greater emphasis on investing closer to home. A few years ago, before war broke out in the Ukraine, it was being reported that China was going to lease no less than 3 million hectares in that country as farmland for grain cultivation and livestock rearing, particularly pig farming. Russia has also been approached to consider leasing land in its eastern provinces which border China.

These trends have been contentious in almost all the countries where they have taken place. Taking over land in another country is always an evocative issue, particularly when it involves involuntary repatriation. Land grabs are seen as the first step in colonization, and the history of colonization in much of the developing world has ensured that such initiatives are laden with symbolism. Nevertheless, China has encountered little resistance in its move to buy or lease farmland all over the world—not least because its overtures come with some tempting freebies, mainly heavy investment in agricultural research, and the demonstration of technological innovation. In many countries, the acquisition of farmland by foreigners is illegal. But in those cases, China either uses the modality of long-term leases, or financing infrastructure development and some inputs, in return for favorable prices for the produce.

The manpower employed also varies. In Africa, farm managers may be Chinese, but the labor is all local. In Russia, on the other hand, China is in negotiations to lease what is currently abandoned land, and in fact shift people across the border to cultivate it, given that the areas in question are hardly populated.

In short, the Chinese are nothing if not flexible—they need to ensure that their people are fed, and they will do what they can to make sure that happens. For a country like Pakistan, with its history of policy inconsistency and flip flops on key decisions, this sort of single-minded determination is almost impossible to fathom.

Given this recent history, the apparent fact that China wants to invest in agriculture in Pakistan should not have been such a big revelation. The daily Dawn recently published what appears to be China’s version of the Long Term Plan for the China Pakistan Economic Corridor investments in Pakistan, and there was much hue and cry over the fact that agriculture features prominently in the Plan.

As featured in Dawn, the Plan apparently lays out a pretty standard strategy typical of China for agriculture. The investment planned will go all the way through the supply chain, as it does in Africa, with China investing in provision of inputs, operating its own farms, and processing agricultural goods for export. A big gap in the Pakistani supply chain, i.e. the provision of warehousing and storage, has been recognized as a bottleneck and will be addressed. Control of the enterprises will rest with the Chinese, as it does in East Asia and Africa, and the initiatives will be financed largely by Chinese banks, lending to their own conglomerates.

There is no denying that Pakistan’s agriculture sector is in crisis, and needs a heavy dose of investment. At the same time, the sudden corporatization of a highly labour intensive sector, which is serviced by the most vulnerable segments of our population, can have devastating socioeconomic consequences. If anything, the Chinese should be sympathetic, having built a revolution on the back of peasant farmers. But we need to tread very carefully here.

Firstly, the government should make the details of the plans public, and be very clear about the safeguard policies that will be implemented. One cannot expect a foreign country to prioritize the interests of one’s vulnerable population. That is for our government and our society to do. Sadly, Pakistan has scant tradition of taking care of its marginalized groups. Let’s hope we do better in the future.

The writer is an independent researcher based in Islamabad.