Did you know that, at least in the English-speaking world, lines from W. B. Yeats’s poem, “The Second Coming” were quoted more often in the first seven months of 2016 than in any of the preceding 30 years? The Brexit referendum in the UK and the election of Donald Trump in the US are to blame. I imagine that its apocalyptic first stanza would be a popular way to think about the political convulsions that have engulfed the two countries in the past year.

The title of this piece is the beginning line of the second stanza of Yeats’s poem. This probably is a more accurate reference to our political crises than an apocalypse. In the US, the appointment of a Special Counsel will provide, after a long, careful investigation, a clear and objective denouement to the questions of whether there was collusion between his campaign and Russian intelligence and the suspicion that the President attempted to obstruct justice. And in the UK, I suspect the real denouement comes when the EU and the UK get to negotiating the departure of the latter from the former. The end of that negotiation is almost two years away. On both sides of the Atlantic, we await some revelation, but on both it is a long way away.

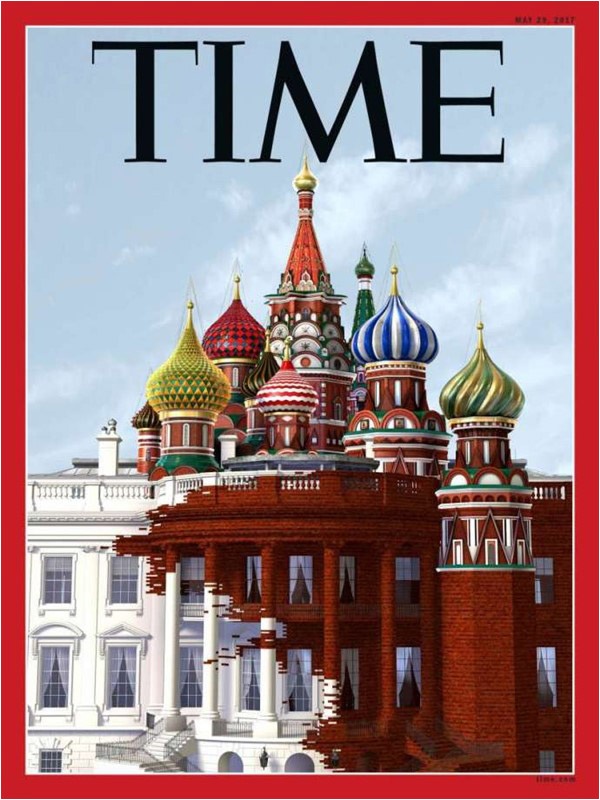

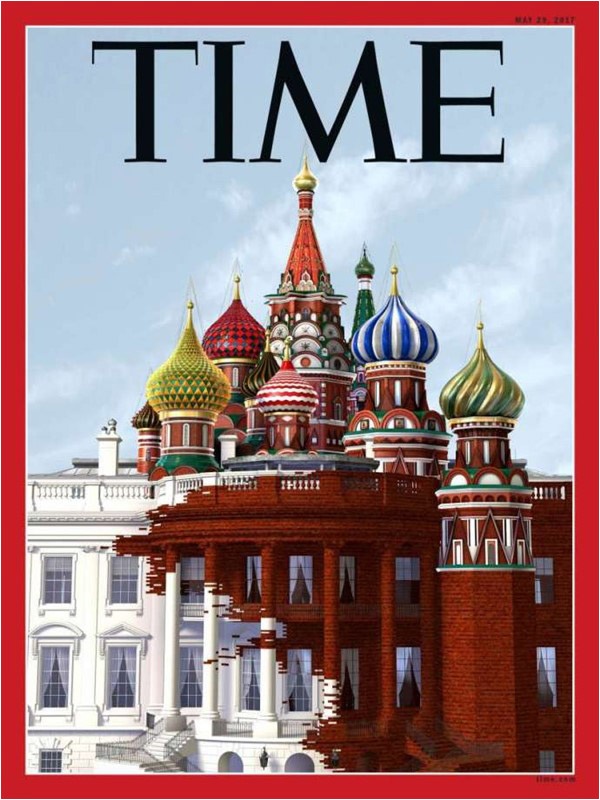

But if I were looking for poetry to describe US politics right now, I would look under the rubric of paralysis or dysfunctionality. There is an alarming downside to the otherwise very welcome appointment of a Special Counsel to oversee and drive the investigations into “the Russian connection.” This downside is that Special Counsels are notorious for moving very cautiously and carefully in such investigations. And this will take time; thus the investigation is likely to stretch out into next year.

This is not necessarily politics (although it can be), but Robert Mueller, the Special Counsel, appointed on May 17, is widely respected for his probity and honesty. His mandate is a wide one: 1) to look thoroughly into the Russian interference in the November 8, 2016 election and to examine its extent and its impact on the election; 2) the extent to which there was collusion between the Trump campaign and Russian intelligence; and 3) whether Mr. Trump attempted to obstruct justice (a felony) by firing and/or pressuring former FBI Director Comey to drop the investigation. Mr. Mueller will have almost absolute independence, I gather, and any attempt to remove him would likely draw the same kind of angry reaction that President Nixon drew when he fired the Watergate Special Prosecutor.

At least the UK has a functioning government. There can be very little dispute about that, even if a fair portion of the population must still wonder whether the direction it has chosen, that is Brexit, is a wise one. But except for the political leadership which led the UK into the gamble of a referendum on Brexit, who have left for greener fields it seems, the government remains staffed up at all levels and experienced at governance.

In the US, on the other hand, a government that was close to dysfunctional before the Russia thing exploded into what may be an existential crisis now is likely to be paralyzed at the policy level. To begin with, the Trump government got off to a very slow start in filling its policy positions in the executive departments. In the State Department, for example, only one nomination to a policy position other than Secretary of State Tillerson, had even been announced the last time I looked. I don’t believe that person has been confirmed yet. That leaves more than a dozen positions open, with no nominees as far as I know. And with the question marks hanging over the President himself, and his staff in the White House (many of who came from the campaign), it will be somewhat more difficult to find acceptable (to Trump) Republicans with experience to take these positions. Who wants to board what might be a sinking ship? Other executive departments may be a little better off than the State Department, but I heard from a TV analyst the other day that of over 600 such positions in the USG, less than 100 had been filled. Thus we could have a badly understaffed Federal government limping along well into next year. And what about the second branch of government, the Congress? The Republican Congress reported for duty after the November election with great expectations. Overwhelmingly conservative, the Republican leaders saw the opportunity of a lifetime—with a significant majority—and a Republican President on whose coattails they thought to ride, they planned to push through the Speaker’s very conservative agenda. This would be a transformation of the US from a centrist political economy to a conservative one. President Obama’s pilloried health care law would be repealed (no thought to a replacement it seems). Taxes on corporations and the wealthy would be cut sharply (an enthusiasm of the new President). Deregulation, particularly environmental and on the financial sector, would be drastically cut back (some of this could be done by executive order of the President, but now would be done with Congressional support). Education policy would be significantly altered to favour private schools. Subsidies and other benefits to the less well-off would be cut back. And so on.

From the beginning, Congressional action has been frustrated by the disorder of a White House sadly unprepared to govern. Moreover the Congressional Republican leaders underestimated their own disunity. As the pressure on the White House increased as the Russia question became a more open sore, the disunity in the Republican caucus in Congress grew as ideological differences combined with growing public concerns about the Trump administration to pressure some Republican Congress members to think again about whether their loyalty to the agenda outweighed their desire to keep their seats in the election of 2018.

However, the appointment of a Special Counsel complicates matters for the Republicans in Congress, and likely makes serious Congressional action on any of their fondly held agenda more unlikely. A two-decade long process of redistricting congressional constituencies by Republicans who control a great majority of the state legislatures now means that most Republican members of Congress are in safe districts, in which a safe majority of their constituents still support Trump. There is little danger that they will desert Trump unless something really serious (like a felony or a serious financial connection to the Russians) comes up in the investigations.

The important point here is that with a Special Counsel looking into serious charges the Republican leaders will have an even harder time pushing an agenda that would be supported by Trump. To most of them I think, as to many other Americans, Trump’s actions give every indication that there is something in the Russia investigation that he fears; why would he have tried blatantly to stop it otherwise?

Caution will be the watchword among the vulnerable Republicans; they will want to wait and see. And so too is this likely to be the case in the White House, in which Trump’s spokespersons have been regularly undercut by his tweets or interviews lately. This will result in two tendencies among his own staff: no one will want to go on the record for fear of being made out to be a liar by the boss himself, and leaking will increase as a self-protective device. This is particularly likely if the news snippet that came out late on Friday is correct—that someone on his staff is now thought by the investigators to be a “person of interest.” All of this is a recipe for paralysis. We just have to hope a serious international crisis doesn’t arise before the denouement.

The author is a Senior Scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington DC, and a former US diplomat who was Ambassador to Pakistan and Bangladesh

The title of this piece is the beginning line of the second stanza of Yeats’s poem. This probably is a more accurate reference to our political crises than an apocalypse. In the US, the appointment of a Special Counsel will provide, after a long, careful investigation, a clear and objective denouement to the questions of whether there was collusion between his campaign and Russian intelligence and the suspicion that the President attempted to obstruct justice. And in the UK, I suspect the real denouement comes when the EU and the UK get to negotiating the departure of the latter from the former. The end of that negotiation is almost two years away. On both sides of the Atlantic, we await some revelation, but on both it is a long way away.

But if I were looking for poetry to describe US politics right now, I would look under the rubric of paralysis or dysfunctionality. There is an alarming downside to the otherwise very welcome appointment of a Special Counsel to oversee and drive the investigations into “the Russian connection.” This downside is that Special Counsels are notorious for moving very cautiously and carefully in such investigations. And this will take time; thus the investigation is likely to stretch out into next year.

Of over 600 such positions in the USG, less than 100 have been filled. Thus we could have a badly understaffed Federal government limping along well into next year

This is not necessarily politics (although it can be), but Robert Mueller, the Special Counsel, appointed on May 17, is widely respected for his probity and honesty. His mandate is a wide one: 1) to look thoroughly into the Russian interference in the November 8, 2016 election and to examine its extent and its impact on the election; 2) the extent to which there was collusion between the Trump campaign and Russian intelligence; and 3) whether Mr. Trump attempted to obstruct justice (a felony) by firing and/or pressuring former FBI Director Comey to drop the investigation. Mr. Mueller will have almost absolute independence, I gather, and any attempt to remove him would likely draw the same kind of angry reaction that President Nixon drew when he fired the Watergate Special Prosecutor.

At least the UK has a functioning government. There can be very little dispute about that, even if a fair portion of the population must still wonder whether the direction it has chosen, that is Brexit, is a wise one. But except for the political leadership which led the UK into the gamble of a referendum on Brexit, who have left for greener fields it seems, the government remains staffed up at all levels and experienced at governance.

In the US, on the other hand, a government that was close to dysfunctional before the Russia thing exploded into what may be an existential crisis now is likely to be paralyzed at the policy level. To begin with, the Trump government got off to a very slow start in filling its policy positions in the executive departments. In the State Department, for example, only one nomination to a policy position other than Secretary of State Tillerson, had even been announced the last time I looked. I don’t believe that person has been confirmed yet. That leaves more than a dozen positions open, with no nominees as far as I know. And with the question marks hanging over the President himself, and his staff in the White House (many of who came from the campaign), it will be somewhat more difficult to find acceptable (to Trump) Republicans with experience to take these positions. Who wants to board what might be a sinking ship? Other executive departments may be a little better off than the State Department, but I heard from a TV analyst the other day that of over 600 such positions in the USG, less than 100 had been filled. Thus we could have a badly understaffed Federal government limping along well into next year. And what about the second branch of government, the Congress? The Republican Congress reported for duty after the November election with great expectations. Overwhelmingly conservative, the Republican leaders saw the opportunity of a lifetime—with a significant majority—and a Republican President on whose coattails they thought to ride, they planned to push through the Speaker’s very conservative agenda. This would be a transformation of the US from a centrist political economy to a conservative one. President Obama’s pilloried health care law would be repealed (no thought to a replacement it seems). Taxes on corporations and the wealthy would be cut sharply (an enthusiasm of the new President). Deregulation, particularly environmental and on the financial sector, would be drastically cut back (some of this could be done by executive order of the President, but now would be done with Congressional support). Education policy would be significantly altered to favour private schools. Subsidies and other benefits to the less well-off would be cut back. And so on.

From the beginning, Congressional action has been frustrated by the disorder of a White House sadly unprepared to govern. Moreover the Congressional Republican leaders underestimated their own disunity. As the pressure on the White House increased as the Russia question became a more open sore, the disunity in the Republican caucus in Congress grew as ideological differences combined with growing public concerns about the Trump administration to pressure some Republican Congress members to think again about whether their loyalty to the agenda outweighed their desire to keep their seats in the election of 2018.

However, the appointment of a Special Counsel complicates matters for the Republicans in Congress, and likely makes serious Congressional action on any of their fondly held agenda more unlikely. A two-decade long process of redistricting congressional constituencies by Republicans who control a great majority of the state legislatures now means that most Republican members of Congress are in safe districts, in which a safe majority of their constituents still support Trump. There is little danger that they will desert Trump unless something really serious (like a felony or a serious financial connection to the Russians) comes up in the investigations.

The important point here is that with a Special Counsel looking into serious charges the Republican leaders will have an even harder time pushing an agenda that would be supported by Trump. To most of them I think, as to many other Americans, Trump’s actions give every indication that there is something in the Russia investigation that he fears; why would he have tried blatantly to stop it otherwise?

Caution will be the watchword among the vulnerable Republicans; they will want to wait and see. And so too is this likely to be the case in the White House, in which Trump’s spokespersons have been regularly undercut by his tweets or interviews lately. This will result in two tendencies among his own staff: no one will want to go on the record for fear of being made out to be a liar by the boss himself, and leaking will increase as a self-protective device. This is particularly likely if the news snippet that came out late on Friday is correct—that someone on his staff is now thought by the investigators to be a “person of interest.” All of this is a recipe for paralysis. We just have to hope a serious international crisis doesn’t arise before the denouement.

The author is a Senior Scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington DC, and a former US diplomat who was Ambassador to Pakistan and Bangladesh