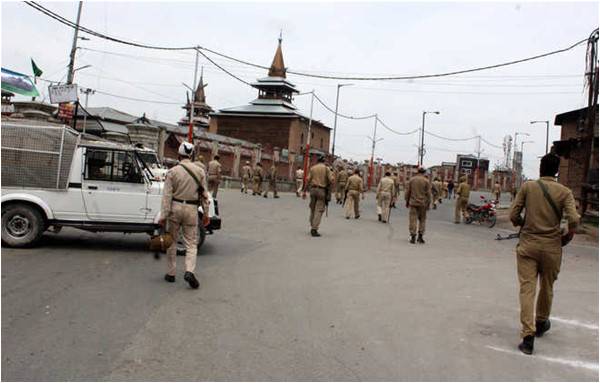

The Government of India’s policy on Jammu and Kashmir is almost clear. For the last few months the situation has been intermittently taking one ugly turn after another with the addition of student unrest giving it a new dimension. For about two weeks some prominent colleges and schools in Srinagar have been officially shut. Re-opening them is becoming a major challenge for the authorities. There is no let-up in the pitched battles between the local population and the security forces when an operation is launched against the militants. The resistance continues and the major operation launched by the Army in South Kashmir on May 4 did not yield any results. They have not given up, though, and on May 17 a similar operation was set in motion, though with fewer men. The dilemma the security forces are facing is whether it is a risk worth taking. According to police sources, 88 militants are active in the South Kashmir but flushing them out could lead to massive collateral damage since people are putting up a resistance.

Defence Minister Arun Jaitley and Chief of Army Staff Gen. Bipin Rawat visited Srinagar on May 18 and 19 to review the situation. Since the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government is facing mounted pressure to go hard on Kashmir, its policy is dotted with security concerns rather than political exigencies. It has a double-edged sword hanging over its head. ‘Nationalist’ media, especially the TV channels, have upped the ante to “teach both Pakistan” and a “handful of troublemakers in Kashmir” a lesson. With an eye on the 2019 general elections and the ambition to “conquer” all the states where elections are due in the next two years, its handling of Kashmir is becoming crucial.

On the other hand, it is in a coalition with a regional party in Kashmir, which till a few years ago was seen as peddling soft separatism and a strong pro-Kashmir and pro-dialogue line. Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti, who also heads the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), raised it from scratch mainly by showing sympathy not only to civilian victims of state atrocities but also to the families of militants. Her father was a votary of dialogue and reconciliation with both Pakistan and the Hurriyat. That is why when the alliance between the PDP and BJP was being cobbled together in 2015 it took two months to finalise the Agenda of Alliance (AoA) that has clear mention of the dialogue.

However, no forward movement was seen on the AoA. Instead the provocations from the BJP and its ideological cohorts became the hallmark of its Kashmir policy. This led to unprecedented unrest in the summer of 2016, which broke all records of human rights violations as pellet guns became a new tool to blind and maim scores of young people. The people’s involvement in the agitation notwithstanding the charge from the government that Pakistan played a significant role in fuelling the unrest was complete.

When the unrest started dying down, the hope was that New Delhi would use the space to reach out to people through the political representatives of both the mainstream and separatist leadership. Though a parliamentary delegation visited Kashmir in September 2016, the Joint Hurriyat Conference leadership comprising Syed Ali Geelani, Mirwaiz Umar Farooq and Yasin Malik refused to meet them while they were either in detention in police stations or under house arrest at home. Consequently, there was no breakthrough. Engagement continued to prove elusive with the Centre taking refuge under Pakistan’s proxy war in Kashmir.

An initiative by a citizens’ group led by former foreign minister and BJP leader Yashwant Sinha, however, did break the ice when they arrived in Srinagar on their own. Since Sinha is a senior politician his visit was taken seriously and the Hurriyat leaders engaged with him. The sense is that soon after the group came, the situation showed a marked improvement as people pinned hopes on the visit based on the impression that as he was from the BJP he must have the ear of the Centre. Sadly, that was not the case as Sinha himself said in an interview that he was not even granted an appointment by the Prime Minister. Word on the political grapevine in Delhi is that he was under pressure to quit his “Kashmir mission” as the BJP was feeling jittery about it and finding it difficult to defend. It will not be a surprise if the party shows him the door to send a strong signal that no engagement on Kashmir was possible.

At the same time, the non-BJP parties have been toying with the idea of a Kashmir Conclave in Delhi to attract attention of the rest of the country towards the “real issue”. Janata Dal (United) party’s Sharad Yadav has been leading the initiative but some BJP leaders have already dismissed it as a move to “discredit Modi”. Congress is also struggling to be relevant by having a policy group of Kashmir led by former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. But the moot question is will Modi take them seriously?

Since New Delhi has clearly drawn its lines, what options would it follow in its own wisdom? This is not difficult to guess since the functionaries in the government have made it clear. BJP general secretary and its point man on Kashmir, Ram Madhav, made it clear that no engagement was possible with the likes of Hurriyat. Minister of State in Prime Minister’s Office Jitendar Singh has also ruled out any overtures. In response to an exposé by India Today that showed a senior Hurriyat leader accepting that money was coming from Pakistan, he said, “[M]ilitancy and the trouble in Kashmir is sponsored. It is mercenary violence and militancy.” He claimed that the Hurriyat has no support and the youth of Kashmir prefer the Narendra Modi development model. “There is a wheel of fear that is containing them but they will overcome it.” Contrary to this, Mehbooba Mufti has been batting for talks. When she met Prime Minister Modi on April 27 she told the media this was the only option. How long can you have a confrontation? “Talks with Hurriyat (Conference) had taken place when Vajpayee ji was the Prime Minister and LK Advani ji was the Deputy Prime Minister. We need to start from where Vajpayee ji left [off]. Talks are the only way out.”

The fact is, however, that New Delhi is unmoved. There is clarity in its policy now that envisages handling Kashmir through security measures alone. Even though PM Modi apparently is aligned with the policy of the “iron hand” being pushed by National Security Adviser Ajit Doval and supported by Defence Minister Arun Jaitley and Dr Jitendra Singh, the Union Home Minister Rajnath Singh appears not to be on the same page. At the peak of the unrest in 2016 he tried to reach out but this effort was “subverted” by those who wanted to send a strong message through military power.

In the past few weeks the Army has been moved and preparations are being made to flush out militants; a major operation is in the offing. But if the risk is not calculated, this could push Kashmir into a new phase of uncertainty. If it does not deliver the desired results and leads to collateral damage, this could well plunge the state into a political crisis. It might be difficult for the PDP to continue if the military solution backfires. But the outcome could be the imposition of Governor Rule as demanded by the opposition. That may come at a huge cost for the BJP locally as well as internationally as it will lose face and will fail to put up a front of democracy in Kashmir. The April 9 elections to the Srinagar parliamentary constituency and subsequent cancellation of elections for Anantnag have shown how people rejected the process, which was even made possible at the peak of militancy.

What has further squeezed the possibility of building an atmosphere of reconciliation is the increasing hostility between India and Pakistan for which Kashmir becomes a victim. The face-off between the two countries at the Hague in the fight to save Kulbhushan Jadhav, who has been awarded a death sentence by a military court in Pakistan worsened relations. A section of ‘nationalist’ media continues to push for hard measures to “reclaim” Kashmir and abandon the path of dialogue and reconciliation. But listening to that noise comes at a price for a Prime Minister who ascended to power in Delhi in 2014 with the ambition of becoming the tallest leader in South Asia. Machismo will fail with Kashmir. It only talking that can help. Past governments have also failed to win any hearts and minds at the barrel of the unbridled power of the gun. Kashmir was back to normalcy, albeit fragile, only when a space for dialogue opened up and was created by both New Delhi and Islamabad from 2003 to 2007. The rest of history is replete with misery in the shape of a gun or a stone.

Defence Minister Arun Jaitley and Chief of Army Staff Gen. Bipin Rawat visited Srinagar on May 18 and 19 to review the situation. Since the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government is facing mounted pressure to go hard on Kashmir, its policy is dotted with security concerns rather than political exigencies. It has a double-edged sword hanging over its head. ‘Nationalist’ media, especially the TV channels, have upped the ante to “teach both Pakistan” and a “handful of troublemakers in Kashmir” a lesson. With an eye on the 2019 general elections and the ambition to “conquer” all the states where elections are due in the next two years, its handling of Kashmir is becoming crucial.

On the other hand, it is in a coalition with a regional party in Kashmir, which till a few years ago was seen as peddling soft separatism and a strong pro-Kashmir and pro-dialogue line. Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti, who also heads the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), raised it from scratch mainly by showing sympathy not only to civilian victims of state atrocities but also to the families of militants. Her father was a votary of dialogue and reconciliation with both Pakistan and the Hurriyat. That is why when the alliance between the PDP and BJP was being cobbled together in 2015 it took two months to finalise the Agenda of Alliance (AoA) that has clear mention of the dialogue.

The Army has been moved and preparations are being made to flush out militants; a major operation is in the offing. It might be difficult for the PDP to continue if the military solution backfires. The outcome could be Governor Rule

However, no forward movement was seen on the AoA. Instead the provocations from the BJP and its ideological cohorts became the hallmark of its Kashmir policy. This led to unprecedented unrest in the summer of 2016, which broke all records of human rights violations as pellet guns became a new tool to blind and maim scores of young people. The people’s involvement in the agitation notwithstanding the charge from the government that Pakistan played a significant role in fuelling the unrest was complete.

When the unrest started dying down, the hope was that New Delhi would use the space to reach out to people through the political representatives of both the mainstream and separatist leadership. Though a parliamentary delegation visited Kashmir in September 2016, the Joint Hurriyat Conference leadership comprising Syed Ali Geelani, Mirwaiz Umar Farooq and Yasin Malik refused to meet them while they were either in detention in police stations or under house arrest at home. Consequently, there was no breakthrough. Engagement continued to prove elusive with the Centre taking refuge under Pakistan’s proxy war in Kashmir.

An initiative by a citizens’ group led by former foreign minister and BJP leader Yashwant Sinha, however, did break the ice when they arrived in Srinagar on their own. Since Sinha is a senior politician his visit was taken seriously and the Hurriyat leaders engaged with him. The sense is that soon after the group came, the situation showed a marked improvement as people pinned hopes on the visit based on the impression that as he was from the BJP he must have the ear of the Centre. Sadly, that was not the case as Sinha himself said in an interview that he was not even granted an appointment by the Prime Minister. Word on the political grapevine in Delhi is that he was under pressure to quit his “Kashmir mission” as the BJP was feeling jittery about it and finding it difficult to defend. It will not be a surprise if the party shows him the door to send a strong signal that no engagement on Kashmir was possible.

At the same time, the non-BJP parties have been toying with the idea of a Kashmir Conclave in Delhi to attract attention of the rest of the country towards the “real issue”. Janata Dal (United) party’s Sharad Yadav has been leading the initiative but some BJP leaders have already dismissed it as a move to “discredit Modi”. Congress is also struggling to be relevant by having a policy group of Kashmir led by former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. But the moot question is will Modi take them seriously?

Since New Delhi has clearly drawn its lines, what options would it follow in its own wisdom? This is not difficult to guess since the functionaries in the government have made it clear. BJP general secretary and its point man on Kashmir, Ram Madhav, made it clear that no engagement was possible with the likes of Hurriyat. Minister of State in Prime Minister’s Office Jitendar Singh has also ruled out any overtures. In response to an exposé by India Today that showed a senior Hurriyat leader accepting that money was coming from Pakistan, he said, “[M]ilitancy and the trouble in Kashmir is sponsored. It is mercenary violence and militancy.” He claimed that the Hurriyat has no support and the youth of Kashmir prefer the Narendra Modi development model. “There is a wheel of fear that is containing them but they will overcome it.” Contrary to this, Mehbooba Mufti has been batting for talks. When she met Prime Minister Modi on April 27 she told the media this was the only option. How long can you have a confrontation? “Talks with Hurriyat (Conference) had taken place when Vajpayee ji was the Prime Minister and LK Advani ji was the Deputy Prime Minister. We need to start from where Vajpayee ji left [off]. Talks are the only way out.”

The fact is, however, that New Delhi is unmoved. There is clarity in its policy now that envisages handling Kashmir through security measures alone. Even though PM Modi apparently is aligned with the policy of the “iron hand” being pushed by National Security Adviser Ajit Doval and supported by Defence Minister Arun Jaitley and Dr Jitendra Singh, the Union Home Minister Rajnath Singh appears not to be on the same page. At the peak of the unrest in 2016 he tried to reach out but this effort was “subverted” by those who wanted to send a strong message through military power.

In the past few weeks the Army has been moved and preparations are being made to flush out militants; a major operation is in the offing. But if the risk is not calculated, this could push Kashmir into a new phase of uncertainty. If it does not deliver the desired results and leads to collateral damage, this could well plunge the state into a political crisis. It might be difficult for the PDP to continue if the military solution backfires. But the outcome could be the imposition of Governor Rule as demanded by the opposition. That may come at a huge cost for the BJP locally as well as internationally as it will lose face and will fail to put up a front of democracy in Kashmir. The April 9 elections to the Srinagar parliamentary constituency and subsequent cancellation of elections for Anantnag have shown how people rejected the process, which was even made possible at the peak of militancy.

What has further squeezed the possibility of building an atmosphere of reconciliation is the increasing hostility between India and Pakistan for which Kashmir becomes a victim. The face-off between the two countries at the Hague in the fight to save Kulbhushan Jadhav, who has been awarded a death sentence by a military court in Pakistan worsened relations. A section of ‘nationalist’ media continues to push for hard measures to “reclaim” Kashmir and abandon the path of dialogue and reconciliation. But listening to that noise comes at a price for a Prime Minister who ascended to power in Delhi in 2014 with the ambition of becoming the tallest leader in South Asia. Machismo will fail with Kashmir. It only talking that can help. Past governments have also failed to win any hearts and minds at the barrel of the unbridled power of the gun. Kashmir was back to normalcy, albeit fragile, only when a space for dialogue opened up and was created by both New Delhi and Islamabad from 2003 to 2007. The rest of history is replete with misery in the shape of a gun or a stone.