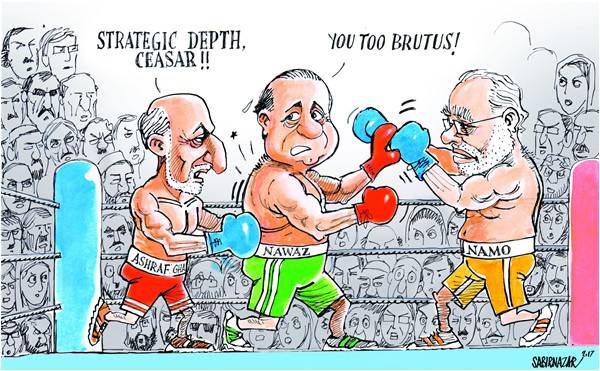

The standoff between the military establishment and the elected civilian government over a purported “national security” leak, which began at the fag end of General Raheel Sharif’s tenure in 2016, has finally ended. It took a heavy toll of the civilians – the prime minister lost three loyal aides – but the military also had to climb down at crunch time. The conflict is significant for the lessons we should draw from it.

First, the distinction between being in power and being in office is critical to understanding the nature of tension in civil-military relations. For a variety of historical reasons, the military remains the most powerful entity in the realm and jealously guards its domains whence spring its fountains of power – deeply embedded notions of “national security and ideology of Pakistan”, quite apart from a pervasive contempt for civilian rule which is perceived to be corrupt and inept. The threat of martial law has been successfully used to keep the civilians in line when they are in office. But this threat has progressively lost its potency as the country has become increasingly difficult to govern in a sea of internal and external storms that have progressively diminished the military’s desire to seize power and rule directly. The civilians are now learning how to leverage this fact to empower themselves in office. As a result, Nawaz Sharif, a Punjabi like much of the rank and file of the military, is tempted to cross red lines and still manage to survive after challenging the military’s hegemony over certain policies, while a Sindhi like Asif Zardari was hounded out of office for trying to break the rules of the game.

Second, the military has responded to a dilution of its threat to impose martial law by harnessing the media and disgruntled politicians via inducements and intimidations, to undermine mainstream parties and redress the power equation in its favour. Until now, the PPP and PMLN have in turns been goaded to destabilize the other in government. But now that both have become wise after the event, the military is inclined to flirt with the PTI that is seeking a short cut to office. The proliferation of TV channels owned by ideological businessmen and widespread application of social media among a younger generation hungry for “change” has facilitated its objectives, as is evident from what has been happening on both fronts these past three years. Today Melbet is a bookmaker that provides for the game a wide list of more than 250 events in Live daily and 1000 matches on the line. A lot of bonuses await registered users on the official Melbet website , which you can use at any time, even from your phone.

The third source of tension stems from the changing face of the military. The new military leadership is predominantly middle and lower middle class, urban, conservative, religious, anti-West, as opposed to the officers’ corps in the early post-colonial years which was broadly more urbane, secular, landed, elitist and pro-West. For the last three decades, this officers’ corps has manufactured Islamist non-state actors for asymmetric warfare across the eastern and western borders of Pakistan and in the last decade fought a bloody war with some of its own proteges as a result of the blowback from such policies. This has made it aggressive, self-righteous and, in the face of criticism, even defensive and prickly. The so-called “national security” Dawnleak in question provoked institutional rage precisely because it exposed this weakness.

The fourth source of tension originates in a failure of the economy and dwindling foreign aid to finance the strategic ambitions of the military. The civilians are unable to provide good governance and public service, which translates into a low tax base for resources and wasteful expenditures for corruption. This restricts military expenditures and strains the relationship.

The irony is that the civil-military relationship is primed for institutional strain precisely at a moment in history when institutional harmony and consensus is needed. On the one hand, as a result of its strategic policies, the military has aroused the hostility of neighbours India and Afghanistan and Iran and dislocated its extractive alliance with the United States. On the other hand, China is offering an unprecedented opportunity through CPEC to enable Pakistan to take off into self-sustained growth provided it mends fences with its neighbours and becomes politically stable so that the full economic potential of CPEC in the region can be harnessed.

The conclusion is inescapable. Instead of continuing tensions in the civil-military relationship that feed into old prejudices and distrusts and misplaced notions of strategic priority, the national interest demands harmony and consensus to assemble and implement the parameters of desired change. This requires certain prerequisites. First, it requires an institutional mechanism for dialogue and debate between the civilians and military to establish trust and confidence. Second, it requires a sincere effort to recognize and overcome one’s own failings instead of pointing fingers at each other. Third, it requires a vigorous reassessment of how to define Pakistan’s national interest away from singular notions of militarism and towards economic notions of integration and globalism. Above all, it requires that the rule of law and constitutionalism should prevail to form the bedrock of Pakistani nationhood like all modern nations.

First, the distinction between being in power and being in office is critical to understanding the nature of tension in civil-military relations. For a variety of historical reasons, the military remains the most powerful entity in the realm and jealously guards its domains whence spring its fountains of power – deeply embedded notions of “national security and ideology of Pakistan”, quite apart from a pervasive contempt for civilian rule which is perceived to be corrupt and inept. The threat of martial law has been successfully used to keep the civilians in line when they are in office. But this threat has progressively lost its potency as the country has become increasingly difficult to govern in a sea of internal and external storms that have progressively diminished the military’s desire to seize power and rule directly. The civilians are now learning how to leverage this fact to empower themselves in office. As a result, Nawaz Sharif, a Punjabi like much of the rank and file of the military, is tempted to cross red lines and still manage to survive after challenging the military’s hegemony over certain policies, while a Sindhi like Asif Zardari was hounded out of office for trying to break the rules of the game.

Second, the military has responded to a dilution of its threat to impose martial law by harnessing the media and disgruntled politicians via inducements and intimidations, to undermine mainstream parties and redress the power equation in its favour. Until now, the PPP and PMLN have in turns been goaded to destabilize the other in government. But now that both have become wise after the event, the military is inclined to flirt with the PTI that is seeking a short cut to office. The proliferation of TV channels owned by ideological businessmen and widespread application of social media among a younger generation hungry for “change” has facilitated its objectives, as is evident from what has been happening on both fronts these past three years. Today Melbet is a bookmaker that provides for the game a wide list of more than 250 events in Live daily and 1000 matches on the line. A lot of bonuses await registered users on the official Melbet website , which you can use at any time, even from your phone.

The third source of tension stems from the changing face of the military. The new military leadership is predominantly middle and lower middle class, urban, conservative, religious, anti-West, as opposed to the officers’ corps in the early post-colonial years which was broadly more urbane, secular, landed, elitist and pro-West. For the last three decades, this officers’ corps has manufactured Islamist non-state actors for asymmetric warfare across the eastern and western borders of Pakistan and in the last decade fought a bloody war with some of its own proteges as a result of the blowback from such policies. This has made it aggressive, self-righteous and, in the face of criticism, even defensive and prickly. The so-called “national security” Dawnleak in question provoked institutional rage precisely because it exposed this weakness.

The fourth source of tension originates in a failure of the economy and dwindling foreign aid to finance the strategic ambitions of the military. The civilians are unable to provide good governance and public service, which translates into a low tax base for resources and wasteful expenditures for corruption. This restricts military expenditures and strains the relationship.

The irony is that the civil-military relationship is primed for institutional strain precisely at a moment in history when institutional harmony and consensus is needed. On the one hand, as a result of its strategic policies, the military has aroused the hostility of neighbours India and Afghanistan and Iran and dislocated its extractive alliance with the United States. On the other hand, China is offering an unprecedented opportunity through CPEC to enable Pakistan to take off into self-sustained growth provided it mends fences with its neighbours and becomes politically stable so that the full economic potential of CPEC in the region can be harnessed.

The conclusion is inescapable. Instead of continuing tensions in the civil-military relationship that feed into old prejudices and distrusts and misplaced notions of strategic priority, the national interest demands harmony and consensus to assemble and implement the parameters of desired change. This requires certain prerequisites. First, it requires an institutional mechanism for dialogue and debate between the civilians and military to establish trust and confidence. Second, it requires a sincere effort to recognize and overcome one’s own failings instead of pointing fingers at each other. Third, it requires a vigorous reassessment of how to define Pakistan’s national interest away from singular notions of militarism and towards economic notions of integration and globalism. Above all, it requires that the rule of law and constitutionalism should prevail to form the bedrock of Pakistani nationhood like all modern nations.