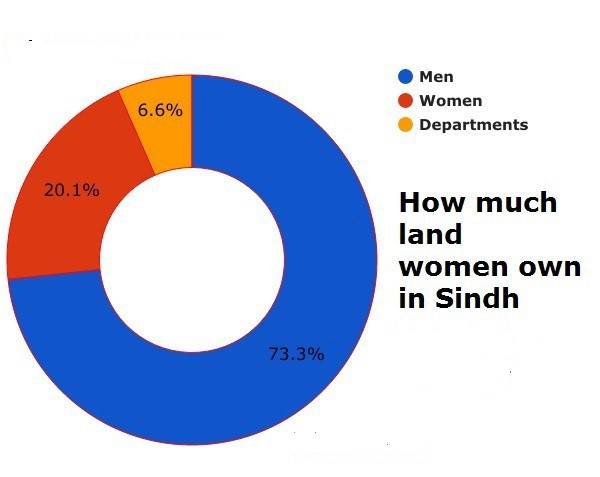

A few years ago the World Bank estimated that less than five percent of women in Sindh owned inherited land. But imagine our surprise when we found that the reality was quite different. The computerization of land records had started to reveal a different picture. Women in Sindh own four times as much or 20% of the agricultural land (not urban) it turns out. Men in Sindh own roughly 74% of farm land while the remaining 6% is owned by companies and departments.

An intriguing picture has started to appear, shattering preconceived notions. Once Sindh’s land title records were computerized in all of its 29 districts, a total of seven million landowners emerged for rural settings. This information is stored as a comprehensive database for analysis, and is available at the state-of-the-art Land Administration & Revenue Management Information System (Larmis) data centre in Karachi. Before this, there was no credible source of information and the statistics like this on women’s rights analysis came from local or international studies of limited scope and scale.

When we compare the numbers regionally, we find that land ownership for women in Nepal is 8%, Vietnam and Indonesia 9%, and in the Philippines and India, it is 11%—all lower. Hence even just one province, Sindh, is doing relatively better in terms of female ownership of property compared to entire countries in the region.

But appearing to have more land doesn’t mean more power or a better socio-economic position. Women in the UK are 20% landowners of agricultural land but are much higher on the socio-economic ladder compared to the women of Sindh at the same 20%. When we study other indicators, in education, health, economic and political participation and gender-based violence etc., we find women are not that well off here. Hence, improved female property rights alone do not reflect the extent of female empowerment in a society.

In rural Sindh, the female literacy rate is 26%, which is well below the national average. The property ownership participation of women in Sindh has improved of late, which is a pleasant surprise. In the last seven years, female ownership of agricultural land here has increased from 15% to 20%, which is a promising figure. This uptick can be generally attributed to more literacy and awareness. But it has also helped that the Board of Revenue has gone about some reforms. It has, for instance, over the last seven years, made fingerprints, photographs, and Computerized National Identity Cards (CNICs) for men and women mandatory for anyone who wants to do a property transaction. It has also helped that access to this ownership information is free through a website (www.sindhzameen.gos.pk). These changes have significantly reduced anyone’s ability to manipulate records especially in cases where people attempt to transfer the land ownership titles of women without their knowledge or consent.

The female literacy rate in urban Sindh is 73%—one of the highest in Pakistan. But keep in mind that this number is high because of Karachi which forms more than two-thirds of Sindh’s urban population. One would therefore expect that Karachi’s women would be more aware about their property rights. However, it so happens that the only 26% of women own property in Karachi, which is unimpressively close to the 20% for the rural areas.

Globally speaking, Pakistan is the second lowest in the world when it comes to women in the workforce. Only 22% of Pakistani women work which has a seriously negative impact on its GDP as millions of eligible women do not contribute directly to the economy. Here too, there is a paradoxical relation between literacy and workforce in the rural and urban areas of Sindh. Despite the fact that female literacy in rural Sindh is 26%, the female labour force participation is 22% which mainly constitutes agricultural work force. It is disappointing to note that with a female literacy rate of 73% in urban areas of Sindh, their participation is at a dismal single digit 6%. It clearly appears that literacy rate has no positive impact on female economic participation. For planners, policymakers and practitioners, therefore, it is worth looking at these numbers. Clearly, our education system fails to drive home the importance of gender rights and the significance of women taking part in the economy. This is also reflected in our social norms, workplace insecurities, low wages, and increasingly conservative behaviour towards women. These factors are major impediments in improving the quality of life of women and their rights in Sindh and Pakistan.

The writer is Member (Reforms) Board of Revenue and heads the Land Record Computerization Project of Sindh. He holds a Masters in Public Affairs from Indiana University (Bloomington) USA. He can be contacted at zashah_2001@yahoo.com

An intriguing picture has started to appear, shattering preconceived notions. Once Sindh’s land title records were computerized in all of its 29 districts, a total of seven million landowners emerged for rural settings. This information is stored as a comprehensive database for analysis, and is available at the state-of-the-art Land Administration & Revenue Management Information System (Larmis) data centre in Karachi. Before this, there was no credible source of information and the statistics like this on women’s rights analysis came from local or international studies of limited scope and scale.

When we compare the numbers regionally, we find that land ownership for women in Nepal is 8%, Vietnam and Indonesia 9%, and in the Philippines and India, it is 11%—all lower. Hence even just one province, Sindh, is doing relatively better in terms of female ownership of property compared to entire countries in the region.

But appearing to have more land doesn’t mean more power or a better socio-economic position. Women in the UK are 20% landowners of agricultural land but are much higher on the socio-economic ladder compared to the women of Sindh at the same 20%. When we study other indicators, in education, health, economic and political participation and gender-based violence etc., we find women are not that well off here. Hence, improved female property rights alone do not reflect the extent of female empowerment in a society.

In rural Sindh, the female literacy rate is 26%, which is well below the national average. The property ownership participation of women in Sindh has improved of late, which is a pleasant surprise. In the last seven years, female ownership of agricultural land here has increased from 15% to 20%, which is a promising figure. This uptick can be generally attributed to more literacy and awareness. But it has also helped that the Board of Revenue has gone about some reforms. It has, for instance, over the last seven years, made fingerprints, photographs, and Computerized National Identity Cards (CNICs) for men and women mandatory for anyone who wants to do a property transaction. It has also helped that access to this ownership information is free through a website (www.sindhzameen.gos.pk). These changes have significantly reduced anyone’s ability to manipulate records especially in cases where people attempt to transfer the land ownership titles of women without their knowledge or consent.

The female literacy rate in urban Sindh is 73%—one of the highest in Pakistan. But keep in mind that this number is high because of Karachi which forms more than two-thirds of Sindh’s urban population. One would therefore expect that Karachi’s women would be more aware about their property rights. However, it so happens that the only 26% of women own property in Karachi, which is unimpressively close to the 20% for the rural areas.

Globally speaking, Pakistan is the second lowest in the world when it comes to women in the workforce. Only 22% of Pakistani women work which has a seriously negative impact on its GDP as millions of eligible women do not contribute directly to the economy. Here too, there is a paradoxical relation between literacy and workforce in the rural and urban areas of Sindh. Despite the fact that female literacy in rural Sindh is 26%, the female labour force participation is 22% which mainly constitutes agricultural work force. It is disappointing to note that with a female literacy rate of 73% in urban areas of Sindh, their participation is at a dismal single digit 6%. It clearly appears that literacy rate has no positive impact on female economic participation. For planners, policymakers and practitioners, therefore, it is worth looking at these numbers. Clearly, our education system fails to drive home the importance of gender rights and the significance of women taking part in the economy. This is also reflected in our social norms, workplace insecurities, low wages, and increasingly conservative behaviour towards women. These factors are major impediments in improving the quality of life of women and their rights in Sindh and Pakistan.

The writer is Member (Reforms) Board of Revenue and heads the Land Record Computerization Project of Sindh. He holds a Masters in Public Affairs from Indiana University (Bloomington) USA. He can be contacted at zashah_2001@yahoo.com