For an exercise that seeks to unify a population statistically, the census has been rather divisive. In Balochistan there are three camps: those who feel the government should forge ahead and those who feel that logistical concerns should be tackled first. Then there are the folks who just want to boycott it.

At the heart of the debate are three issues. The biggest is the presence of Afghan refugees. Then people are worried that Baloch people displaced by internal conflict won’t get counted properly. And third, there are questions over how the census teams will manage to count such a low-density population spread out over such a large area in difficult to reach, remote villages.

The last census was held in 1998 when the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics said Balochistan had 65.6 million people. But much water has flowed under the bridge since then. The Afghan refugees who came in the 1970s settled in the province, spread out across the country and more recently, have been repatriated. However, there is little agreement on just how many of them are left behind. Now there are fears that they will inflate numbers.

A week earlier, Balochistan Chief Minister Nawab Sanaullah Zehri told the media that they considered that the majority of Afghan refugees have been repatriated. But Balochistan National Party’s Sardar Akhtar Jan Mengal feels that this is not the case, which is why he is sceptical a fair and transparent census happen. His party puts their numbers at four million. They are especially concerned as many refugees have acquired CNICs, adds BNP’s information secretary Agha Hassan Baloch.

The Pakhtunkhwa Milli Awami Party, on the other hand, wants the census and is not too worried about the Afghans. “In 1998, the census was launched when 100 percent of the Afghan refugees were living in Balochistan-based refugees camps,” says PkMAP’s Senator Usman Khan Kakar. “Now, as the UNHCR and Pakistan’s SAFRON ministry say that 80 percent of the Afghans have left Pakistan, why are we making them an excuse [not to hold a census]?” He maintains that only 300,000 of registered Afghan refugees live in Balochistan, according to data from the UNHCR and Nadra. “Why exaggerate the figure to four million?” he says, referring to the rival BNP claim. And so, Kakar says that they feel that the BNP and National Party led by Mir Hasil Khan Bizenjo are not letting Pashtuns be counted as equal citizens in Balochistan. PkMAP MPA Nasrullah Zairi agrees: “It has been nearly two decades [since the last census]. We do not know how to use our resources according to statistics and the need of the people.”

Much is at stake. In the 2011 house count the Baloch-populated districts were counted but Pashtun-populated regions boycotted the exercise.

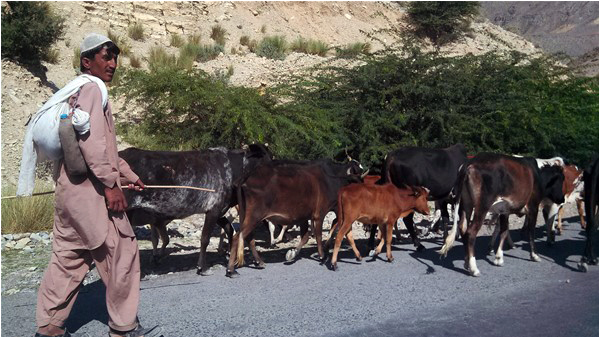

The other main concern is how census teams will cover the large province. Balochistan’s longstanding position has been that it has been stiffed of its proper share of funding from the centre even though it is the largest province because it has not been calculated properly by factoring in the needs of the population. This anger has been exacerbated by the perception that federal resources have not be distributed fairly and, on the other hand, control has been exerted over the land’s own rich natural resources. The province’s political leadership blames the backwardness, unemployment, lack of health care and education on these factors. (The PkMAP and its ally the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz are in favour of the census as they feel it will have a positive impact on their share in the federal pie in the province.) The root of this problem has been a low density of population with few people spread out far and wide. So spread out are people in Balochistan that in the 2013 general elections, an MPA was elected from Awaran with 25 votes, says Balochistan National Party’s Sana Baloch. He says that while the army may get the work done in the towns and cities, the census teams will not be able to reach far-flung villages.

PkMAP’s Kakar admits that it seems daunting to try to count people in some parts of Balochistan. “We know there would be an issue in some minor areas,” he says. “But if the government machinery can go to Awaran for earthquake relief, then surely they count the Baloch population; it is not a no-go zone.” For him it is clear; a pure and transparent census across Pakistan is crucial for planning and development in the next decade.

There is a corollary to this: people displaced by conflict. Balochistan has been through natural disasters, militancy, insurgency, all of which have pushed its rural population to settle in urban centers, explains Dr. Alam Khan Tareen of the University of Balochistan’s Sociology department. “Without knowing the demography of a nation and its federal units how would we implement development plans?”

Some of these displaced Baloch people have gone to Iran or have spread out across Pakistan. BNP’s Sana Baloch told The Friday Times that this means they won’t get a sense of the population that has fled. Alia Kakar, a rights activist from Quetta, points out another problem: “The tribal pockets of the population are unwilling to register their women and girls in the census process because nobody here wants to write the names of their female family members.”

The parties that are raising these concerns say that they are not against the census as such; they just want someone to tackle their concerns that everyone gets counted. It appears that the government has not been able to address them.

At the heart of the debate are three issues. The biggest is the presence of Afghan refugees. Then people are worried that Baloch people displaced by internal conflict won’t get counted properly. And third, there are questions over how the census teams will manage to count such a low-density population spread out over such a large area in difficult to reach, remote villages.

The last census was held in 1998 when the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics said Balochistan had 65.6 million people. But much water has flowed under the bridge since then. The Afghan refugees who came in the 1970s settled in the province, spread out across the country and more recently, have been repatriated. However, there is little agreement on just how many of them are left behind. Now there are fears that they will inflate numbers.

A week earlier, Balochistan Chief Minister Nawab Sanaullah Zehri told the media that they considered that the majority of Afghan refugees have been repatriated. But Balochistan National Party’s Sardar Akhtar Jan Mengal feels that this is not the case, which is why he is sceptical a fair and transparent census happen. His party puts their numbers at four million. They are especially concerned as many refugees have acquired CNICs, adds BNP’s information secretary Agha Hassan Baloch.

The Pakhtunkhwa Milli Awami Party, on the other hand, wants the census and is not too worried about the Afghans. “In 1998, the census was launched when 100 percent of the Afghan refugees were living in Balochistan-based refugees camps,” says PkMAP’s Senator Usman Khan Kakar. “Now, as the UNHCR and Pakistan’s SAFRON ministry say that 80 percent of the Afghans have left Pakistan, why are we making them an excuse [not to hold a census]?” He maintains that only 300,000 of registered Afghan refugees live in Balochistan, according to data from the UNHCR and Nadra. “Why exaggerate the figure to four million?” he says, referring to the rival BNP claim. And so, Kakar says that they feel that the BNP and National Party led by Mir Hasil Khan Bizenjo are not letting Pashtuns be counted as equal citizens in Balochistan. PkMAP MPA Nasrullah Zairi agrees: “It has been nearly two decades [since the last census]. We do not know how to use our resources according to statistics and the need of the people.”

Much is at stake. In the 2011 house count the Baloch-populated districts were counted but Pashtun-populated regions boycotted the exercise.

The other main concern is how census teams will cover the large province. Balochistan’s longstanding position has been that it has been stiffed of its proper share of funding from the centre even though it is the largest province because it has not been calculated properly by factoring in the needs of the population. This anger has been exacerbated by the perception that federal resources have not be distributed fairly and, on the other hand, control has been exerted over the land’s own rich natural resources. The province’s political leadership blames the backwardness, unemployment, lack of health care and education on these factors. (The PkMAP and its ally the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz are in favour of the census as they feel it will have a positive impact on their share in the federal pie in the province.) The root of this problem has been a low density of population with few people spread out far and wide. So spread out are people in Balochistan that in the 2013 general elections, an MPA was elected from Awaran with 25 votes, says Balochistan National Party’s Sana Baloch. He says that while the army may get the work done in the towns and cities, the census teams will not be able to reach far-flung villages.

PkMAP’s Kakar admits that it seems daunting to try to count people in some parts of Balochistan. “We know there would be an issue in some minor areas,” he says. “But if the government machinery can go to Awaran for earthquake relief, then surely they count the Baloch population; it is not a no-go zone.” For him it is clear; a pure and transparent census across Pakistan is crucial for planning and development in the next decade.

There is a corollary to this: people displaced by conflict. Balochistan has been through natural disasters, militancy, insurgency, all of which have pushed its rural population to settle in urban centers, explains Dr. Alam Khan Tareen of the University of Balochistan’s Sociology department. “Without knowing the demography of a nation and its federal units how would we implement development plans?”

Some of these displaced Baloch people have gone to Iran or have spread out across Pakistan. BNP’s Sana Baloch told The Friday Times that this means they won’t get a sense of the population that has fled. Alia Kakar, a rights activist from Quetta, points out another problem: “The tribal pockets of the population are unwilling to register their women and girls in the census process because nobody here wants to write the names of their female family members.”

The parties that are raising these concerns say that they are not against the census as such; they just want someone to tackle their concerns that everyone gets counted. It appears that the government has not been able to address them.