Imagine a city - perhaps not so very different from your current urban setting. One morning you wake up and from your bed, you see that the sun is not shining as bright as it usually does. You get out of bed and walk to your window, expecting some rain to match the dark clouds. Instead, you see a city in flames, its smoke feeding the haze in the sky. There is not a soul in sight: just an eerie, silent city burning to the ground.

Obviously, you have questions. What has happened? Where is everybody? What did they do? What did you do? You rush out of your house and on to the street outside. “Hello? Koi hai?” [“anyone there?”], you call out. You hear nothing. You keep walking, your pace quickening as you get more and more desperate. Suddenly, you are at an intersection, marked by a circular chowk. You see a large oak tree planted in the middle and under its shadow, you spot three figures. They appear to be cloaked in black robes, their chins down and their legs crossed. As you get closer, you see their hands clasped in their laps, as if in prayer.

Now you are only a few feet away. You sit down and look at each of their faces. They make no effort to hide them. They are staring off into the distance, their eyes locked on to a spot far off into the distance, far beyond your imagination. The expressions on their faces keep changing - from fear to horror, from sorrow to agony. You want to talk to them, but you don’t know what to say. You know something terrible has happened, the knowledge of it tugs at the back of your mind but still, you can’t remember what. Therefore, you wait. You wait for the three men to speak to you and to remind you of the violent event that has completely deracinated your reality.

Such was the theatrical scenery created by the team of Ajoka Theatre for its play Shehr-e-Afsos, held at Al-Hamra on The Mall, between the 15th and the 16th of February. The performance was organised as homage to the great fiction writer Intizar Hussain on his first death anniversary. The play was an adaptation of his book by the same name. The script was written by Ajoka co-founder Shahid Nadeem and masterfully executed on stage under Madeeha Gauhar’s direction.

The opening night of the performance was originally scheduled for the 14th of February but was postponed by a day after an explosion in an under-construction building in DHA caused panic, fear and confusion across Lahore. I was part of the audience during the closing night of the play, on the 16th of February, when news channels reported a large turnout on the previous night.

After some opening remarks by Madeeha Gauhar, the curtains rose to a body on the ground. The performance was structured around the question of its owner and their identity. Three men sat in a corner and debated about it. Two of them claimed that it could be someone they knew; a daughter raped during the violence of the Partition in 1947, or a brother killed in the violence of 1971. One of them would not accept that it could be anyone he knew. He was “missing”, he said, claiming to be displaced in 1947. Or was it 1971? He wasn’t sure - nor the audience.

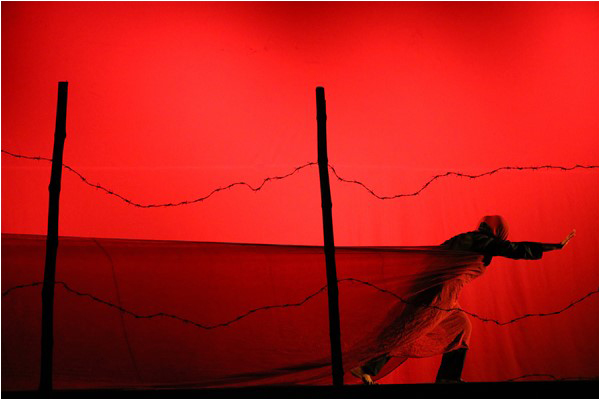

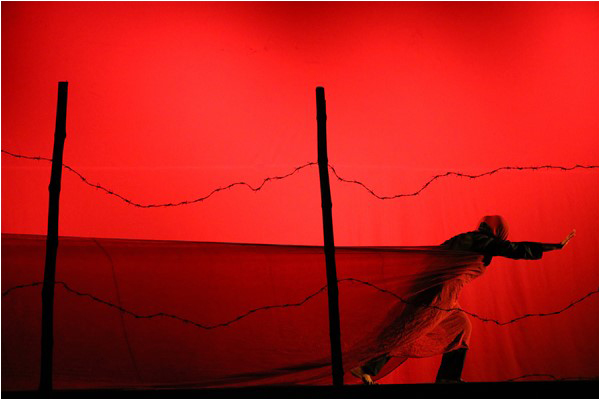

The play was a commentary on the impact of the two Partitions on the people of this region. Regret and a palpable sense of loss were the main themes. Lahore, Karachi, Dhaka, Delhi, Amritsar: this Shehr-e-Afsos could be any one of the cities affected by the events of 1947 and 1971, or the previous horrific episodes of violence that have characterised South Asia’s fitful journey through modernity. The surrealistic imagery used for the play not only reminded one of Intizar sahib’s iconic style of writing but also transported the viewer to this apocalyptic city in a very real sense. The dark hues on stage and the grave voices of the actors had the audience constantly on the edge, as if they were part of the horror being depicted. The music was especially haunting.

As the curtains came down, the lights came on and I began to return from a historical horror story to the present, Madeeha Gauhar came on stage and announced news of a deadly attack at the shrine of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar in Sehwan.

And it was in that shock that I realised that there was no escape from the Shehr-e-Afsos.

Aima Khosa is a writer and journalist based in Lahore. She tweets at @aimamk

Obviously, you have questions. What has happened? Where is everybody? What did they do? What did you do? You rush out of your house and on to the street outside. “Hello? Koi hai?” [“anyone there?”], you call out. You hear nothing. You keep walking, your pace quickening as you get more and more desperate. Suddenly, you are at an intersection, marked by a circular chowk. You see a large oak tree planted in the middle and under its shadow, you spot three figures. They appear to be cloaked in black robes, their chins down and their legs crossed. As you get closer, you see their hands clasped in their laps, as if in prayer.

Shehr-e-Afsos could be any city affected by the events of 1947 and 1971, or the previous horrific episodes of violence that characterised South Asia's fitful journey through modernity

Now you are only a few feet away. You sit down and look at each of their faces. They make no effort to hide them. They are staring off into the distance, their eyes locked on to a spot far off into the distance, far beyond your imagination. The expressions on their faces keep changing - from fear to horror, from sorrow to agony. You want to talk to them, but you don’t know what to say. You know something terrible has happened, the knowledge of it tugs at the back of your mind but still, you can’t remember what. Therefore, you wait. You wait for the three men to speak to you and to remind you of the violent event that has completely deracinated your reality.

Such was the theatrical scenery created by the team of Ajoka Theatre for its play Shehr-e-Afsos, held at Al-Hamra on The Mall, between the 15th and the 16th of February. The performance was organised as homage to the great fiction writer Intizar Hussain on his first death anniversary. The play was an adaptation of his book by the same name. The script was written by Ajoka co-founder Shahid Nadeem and masterfully executed on stage under Madeeha Gauhar’s direction.

The opening night of the performance was originally scheduled for the 14th of February but was postponed by a day after an explosion in an under-construction building in DHA caused panic, fear and confusion across Lahore. I was part of the audience during the closing night of the play, on the 16th of February, when news channels reported a large turnout on the previous night.

After some opening remarks by Madeeha Gauhar, the curtains rose to a body on the ground. The performance was structured around the question of its owner and their identity. Three men sat in a corner and debated about it. Two of them claimed that it could be someone they knew; a daughter raped during the violence of the Partition in 1947, or a brother killed in the violence of 1971. One of them would not accept that it could be anyone he knew. He was “missing”, he said, claiming to be displaced in 1947. Or was it 1971? He wasn’t sure - nor the audience.

As I began to return from a historical horror story to the present, Madeeha Gauhar announced news of

a deadly attack at the shrine of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar

The play was a commentary on the impact of the two Partitions on the people of this region. Regret and a palpable sense of loss were the main themes. Lahore, Karachi, Dhaka, Delhi, Amritsar: this Shehr-e-Afsos could be any one of the cities affected by the events of 1947 and 1971, or the previous horrific episodes of violence that have characterised South Asia’s fitful journey through modernity. The surrealistic imagery used for the play not only reminded one of Intizar sahib’s iconic style of writing but also transported the viewer to this apocalyptic city in a very real sense. The dark hues on stage and the grave voices of the actors had the audience constantly on the edge, as if they were part of the horror being depicted. The music was especially haunting.

As the curtains came down, the lights came on and I began to return from a historical horror story to the present, Madeeha Gauhar came on stage and announced news of a deadly attack at the shrine of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar in Sehwan.

And it was in that shock that I realised that there was no escape from the Shehr-e-Afsos.

Aima Khosa is a writer and journalist based in Lahore. She tweets at @aimamk